Cultural appreciation versus appropriation —borrowing, copying, and being influenced. I believe that there is no architecture without a careful understanding of precedent. Being Swiss, I was early-on made aware that one of the country’s strengths was that the concept of originality lays in the practice of reinventing rather than inventing new ideas.

At first glance, it is about the subtle and perhaps innocent addition of a prefix -re- to a word, but in terms of significance, it does create an important distinction. In fact, I’d like to argue that in architecture and art in particular, this difference paves two different philosophical positions about how one thinks of creating a work of architecture or art. Bluntly stated, I favor reinventing rather than inventing and this for the following reasons.

What is an original?

To remodel, regenerate, refurbish, retype, return, retrace or to renew, to name a few, suggests a position where one returns and goes back to revisit an idea (be it original or already reexamined). This mindset suggests, for me, a degree of humility in the acceptance that a thing or an idea precedes us. While we can always see ourselves as able to create anew, it is important to acknowledge that we are part of a continuum and understand that any act of creation relies on antecedence, regardless of how we read or interpret the past.

Case in point, when teaching architecture and focusing on the topic of inventing, I share with my students that when I look at them, I can imagine their parents and grandparents’ physiognomy based on the son or daughter, thus why not accept that architecture is likewise about incorporating precedent and the ability to own its disciplinary history, similarly to the students being proud of their family identity.

Authenticity

Within this context, and for this blog, the question is not so much about the philosophical distinction between inventing and reinventing, but more about our ability to produce an authentic work of art while exhibiting an understanding of the past, or being integral to a past, thus reinventing. Here, the notions of copying, borrowing and being influenced become, for students, essential pedagogical strategies to make their mark in the design process. But how does one create something original, yet belonging to something larger and part of an existing train of thought or important material culture?

Borrowing

As a first-year student in architecture, a time when I was exposed to the discipline of architecture rather than being given an introduction to design principles across many disciplines, I remember vividly my foolishness in incorporating —without much conviction— the latest styles or shapes learned in history and theory classes.

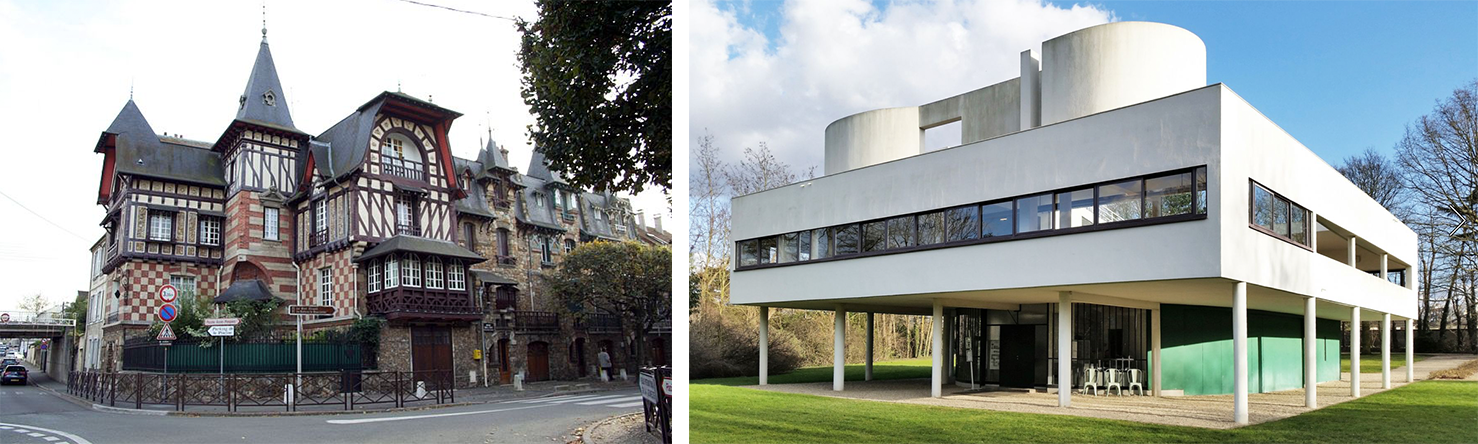

Mies van der Rohe designed my roof structure, while Le Corbusier’s free plan defined my plan, all while allowing Gerrit Rietveld’s de Stijl spatial composition to dictate my functional interpretation of the program’s brief. (These were three of the most important space plans invented in the early 20th century.) To be honest, I don’t remember it being so eclectic, but nevertheless the difficulty I faced was how to understand what I was learning and apply it appropriately to my design projects.

Copying

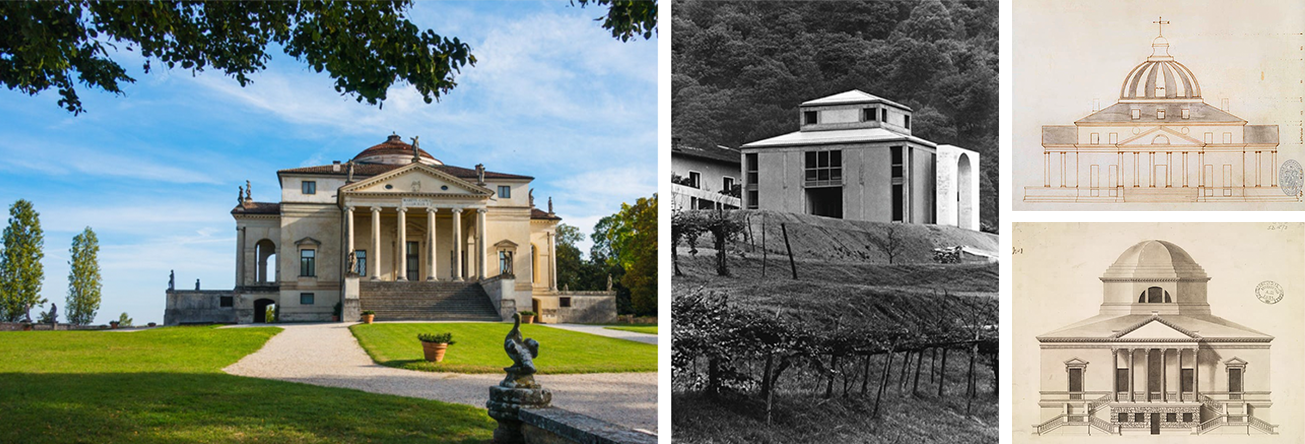

I wasn’t the only student with this conundrum, and with mentoring by my faculty, I decided to copy a famous architectural plan and section, in this case of the Villa Capra (Rotonda) designed by 16th century Italian architect Andrea Palladio (1508 – 1580). This allowed me to understand the notion of case studies and learn about the multiples thoughts and decisions that made the work I analyzed magic. In fact, after this endeavor, I realized why the Villa Capra is an example that all students in architecture needed to know. The exercise was an easy way to see and observe by understanding principles behind the architect’s process, and my understanding of the villa was more complex in its far-reaching repercussions than I could have ever imagined.

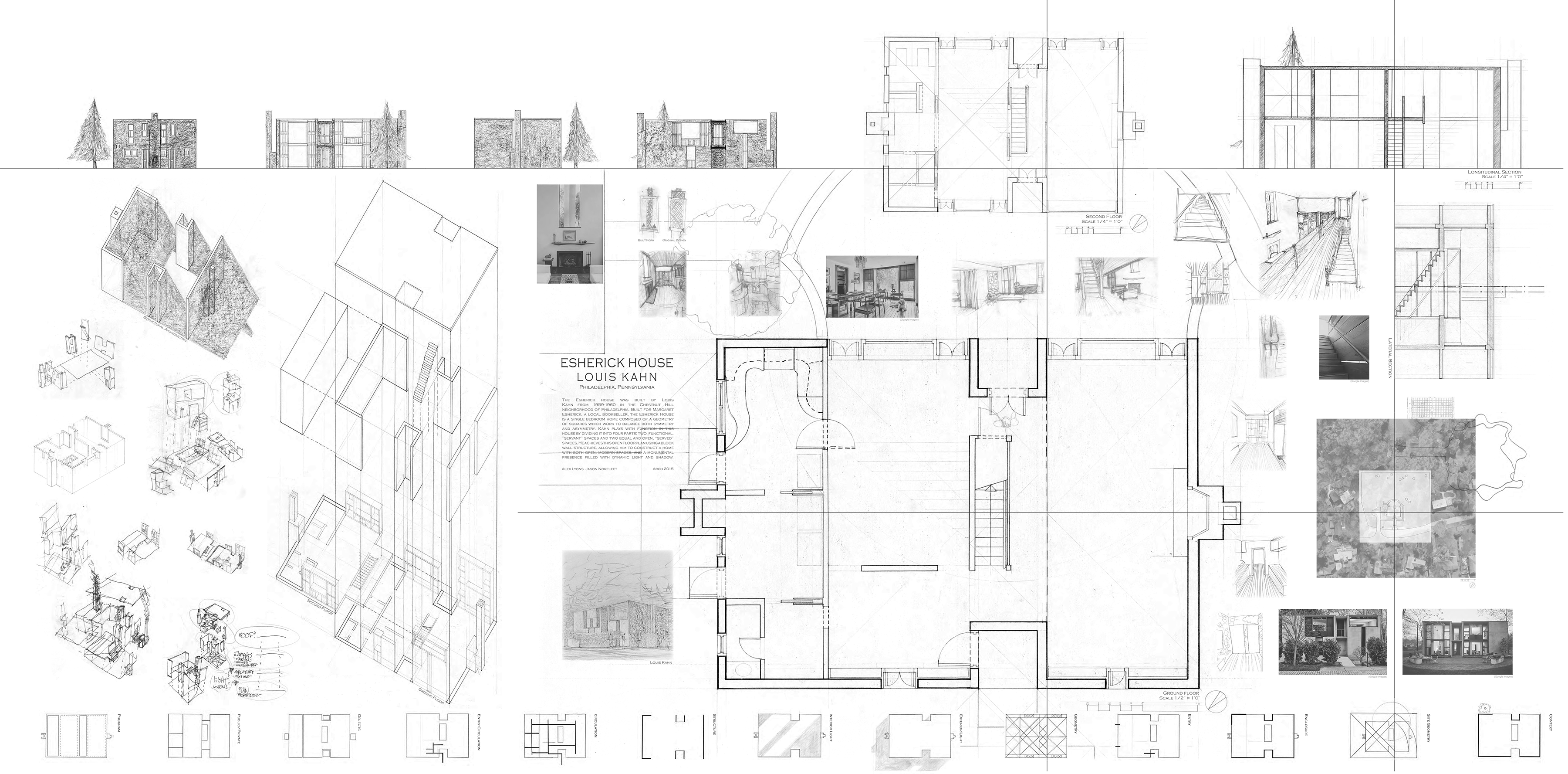

This essential practice to learn by observing and copying, led me on two parallel avenues. First, to discover the possibilities of how architects handled space and place, and second, in abstract terms, to reconstruct and investigate the process that went into the design of a built work. Later, as a faculty member, I came to understand how this method of instruction seemed to be of interest and great pedagogical merit far beyond the mere evaluation of a “finished product.” This is especially true and timely, as the current generation of students have immediate access to readily available images, often without much discrimination and discernment beyond the ease of an Instagram consumption based on “I like it” or “I don’t like it.”

In turn, this process of analysis set in place for me rules of interpretation as they pertained to the first forays into my own design interests. To look at examples from history stressed the importance of examining precedents in order to find connection to my own contemporaneity and work. To analyze, take apart, and examine an object or an existing building (to de-construct without the style of the late 80′) became an important learning process, which without discipline and insight, might at times have hindered me from creating something meaningful both culturally and spatially.

In fact, the analysis project required that I capture, comprehend, and dissect the context of existing buildings within the “flat space” of orthographic drawings, all while understanding their three-dimensional spatial, structural and material reality. It was a win-win situation and to boot, I came to understand why Palladio’s architecture remains so influential, even to die-hard protagonists of the modern movement.

Being influenced

What would I do with all this information, now that I understood that it was of little value to borrow and simply copy what I had come to admire in seminal architectural works? Perhaps the idea of being influenced was a mark of maturity as I honed my skills as a designer and future architect.

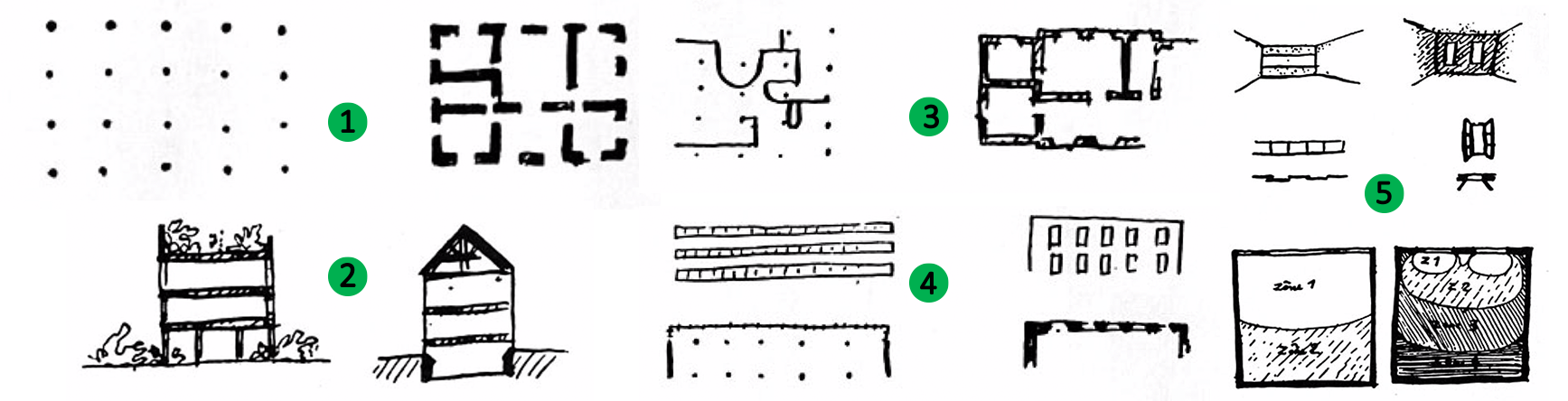

Case in point. When I teach the early design years, I often talk about the work of Swiss architect Le Corbusier (1887 – 1965), and most often about his ability to provoke us through seemingly dogmatic yet powerful conceptual principles. One aspect that I never fail to explore with my students pertains to the famous five points announced in his seminal 1929 book Towards a New Architecture. Not only are these principles recurrently and obsessively found throughout his oeuvre in the pursuit of creating a modern and just architecture, but they are explicated in a particular order, which is the point I am always eager to share with students.

The five points

- the pilotis (load bearing columns)

- the roof garden

- the free plan

- the free façade

- the ribbon window

This order is important for the following reasons: Le Corbusier’s pilotis (1) engage the site, and define the first ordering principle that belongs to the locus of our terrestrial identity; then there is the roof garden (2) that defines the upper limit of the architecture and is metaphorically the principle that rules our larger belonging to the cosmos; all three remaining principles are found in between those two first limits; one finds the free plan (3), the free façade (4) and the ribbon window (5) that place no additional constraints on how space is defined. Everything is free, everything is now possible in pursuit of a modern spatial environment between earth (1) and cosmos (2), inside and outside the architecture.

These five points define Le Corbusier’s language throughout the six decades of his career. And yet, to understand them conceptually, I realized as a student and young architect, that I no longer needed to borrow nor copy those shapes. I “owned’ and understood the forms as ideas, and was now able to be influenced by their historical pertinence, while making my own mark on the art of space making. Perhaps this is what differentiates a cultural appreciation from a formal appropriation.

Conclusion

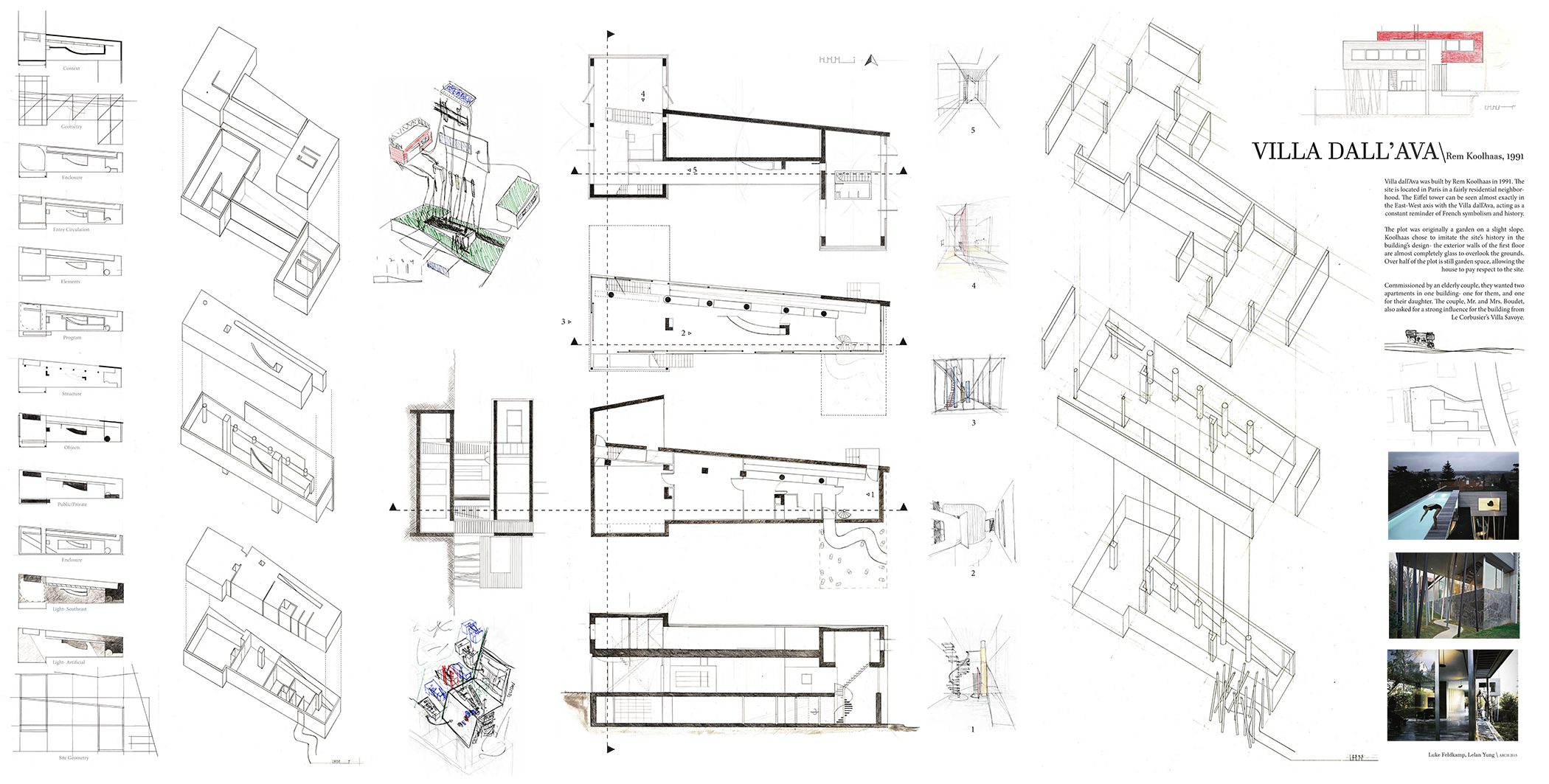

The following examples are taken from my second-year students’ case study analysis where not only where they asked to analysis a particular house project, but finalize their findings in a final presentation.

Citroen House, Le Corbusier (1920-1930)

Esherick House, Louis I. Kahn (1959)

Maison D’all’Ava (1991)

For additional case-study presentation drawings