How to think spatially. I remember as a first-year student during my studies at the Ecole Polytechnique Féderale de Lausanne (EPFL), having a number of questions that kept me awake countless nights, leaving me often without tangible answers.

How to think spatially. I remember as a first-year student during my studies at the Ecole Polytechnique Féderale de Lausanne (EPFL), having a number of questions that kept me awake countless nights, leaving me often without tangible answers.

How to design, what was the difference between a building and architecture, how to incorporate precedence without copying, and where do ideas come from? These seemed to me all legitimate and challenging questions. My only consolation at that time was the realization that I was not alone in the quest for answers.

While these preoccupations, and many others, became more apparent during my professional life—without begging for any final resolution as learning is a lifelong process—how to think spatially was perhaps the most pertinent and difficult question that loomed over my head as I embarked on a career as an architect.

The foundational education that was imparted to me, especially as a freshman, immersed us as students in learning the vocabulary, grammar, and syntax of architecture through the analysis of vernacular barns and domestic houses. Needless to say, many of us were bewildered that vernacular architecture was even considered an underpinning of our education, especially as the term vernacular in architecture signifies an environment built by non-formally schooled architects.

Yet, what seemed at first a contradictory design process (learning to become architects by analyzing buildings by non-architects), by the end of the year we gained a lifelong appreciation for universal human gestures, indigenous skills, and the knowledge that materials, regional identities, climate constraints, and local and cultural practices were all key to an architecture of substance; one that has a soul and exhorts authenticity. Retrospectively, these values are again central to today’s issues, including building a more sustainable environment.

Within today’s pressing concerns about climate issues and the health of the environment, this pedagogical strategy was to become for me and generations of students, an invaluable lesson in understanding an architecture based on the need for:

- an economy of means

- a principle of settlement, and

- the creation of a model of life

While faculty gave equal value to both didactic and Socratic methods, students acquired basic drawing and verbal skills, and learned about the need for an interdisciplinary approach between architecture, structure, landscape, and material culture. While I cannot thank my professors enough for imparting me with such essential concepts, the question of how to think spatially in architecture remained an imprecise idea, despite seemingly successful design studio projects.

It was only in my second year, under the mentorship of painter Robert Slutzky (1929-2005) that I came to slowly understand the meaning of how to think spatially, particularly through my attempts to translate ideas into space and place. Bob shared so many delightful insights, proposed out-of-the-ordinary ideas and questions (i.e., musical and purist relationship to architecture, and why are the ingredients of a cheeseburger not stacked symmetrically), I remember one day, he challenged us about the nature of the plan and section:

When we drew a plan, we were to think in section, and conversely,

when we represented a section, we should think in plan.

Working in this manner would allow us to coordinate our design in three dimensions. Despite the remarks being both simple and complex, the intensity of this moment was a true revelation.

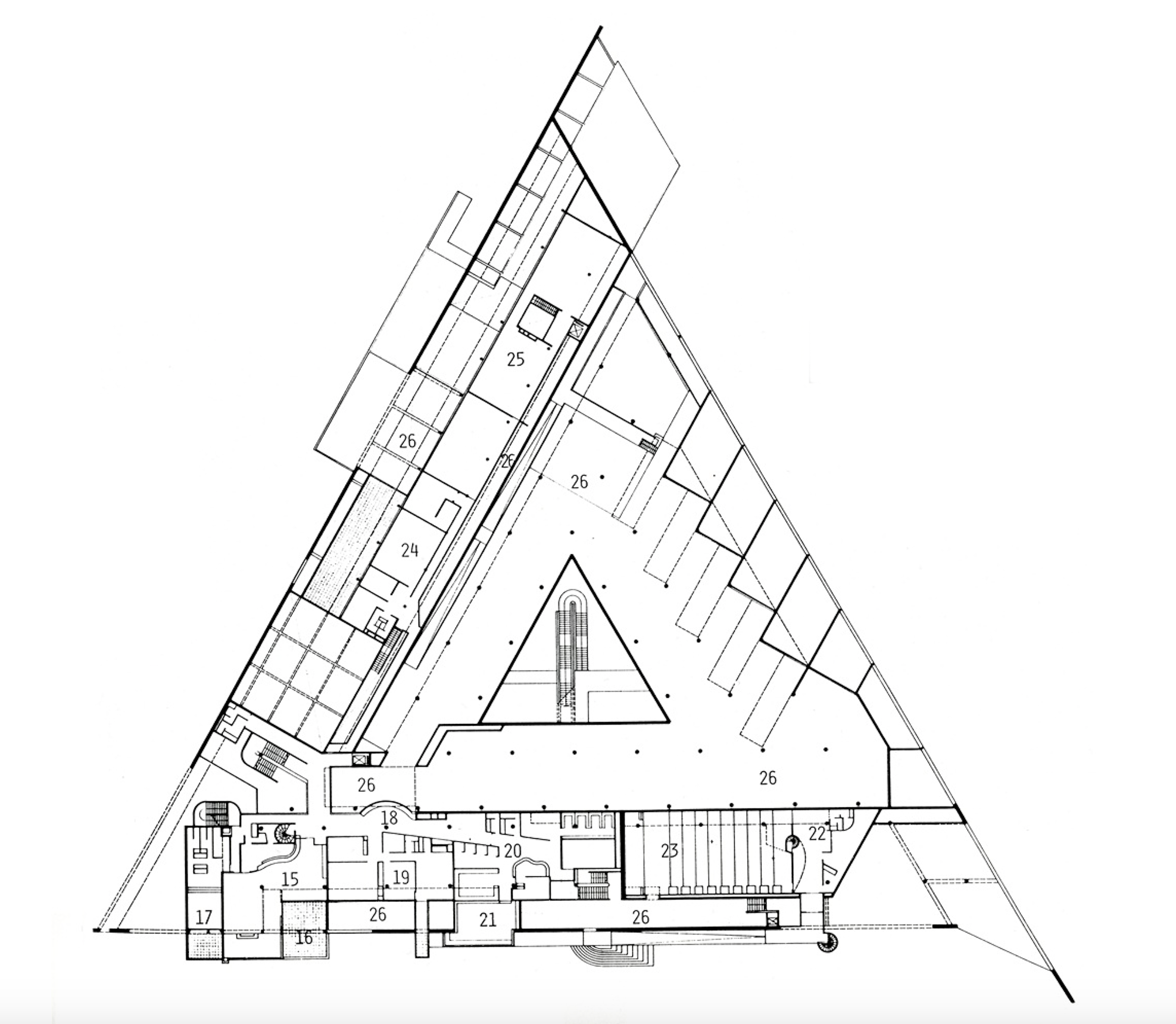

Comprehending and implementing these thoughts in my project, was far from easy, especially as I was already struggling to understand the profundity of Le Corbusier’s statement that “the plan is the generator;” let alone that the notion of section was quasi absent at that time as a key design tool. Unfortunately, I recognize that emphasizing the plan without its corresponding section is still alive within today’s studio culture. While I was a student, and, as the idea of reciprocity between plan and section gained traction, yet remained inelegantly expressed in my design process, I realized the following:Henri Ciriani. Archeological Museum, City of Arles, France, 1995

- When I draw a plan, I not only try to find order in how I distribute and interpret functional requirements, but I define spaces through a set of codes or an established system of architectural notifications. A dot at a certain scale represents a structural column, while a certain line thickness denotes either a structural wall or partition wall, the latter being nonstructural. A set of identical parallel lines drawn in rapid succession, one above each other, express a stair, and dashed lines may indicate important spatial conditions—that are above the sectional cut in plan and have a direct influence on the perception of space. All of these symbols expressed in plan and at a specific scale, gain particular spatial meaning in section, especially as their abstract and static representations in plan are promptly replaced by human movement in time and space, and this through mental coordination between plan and section.

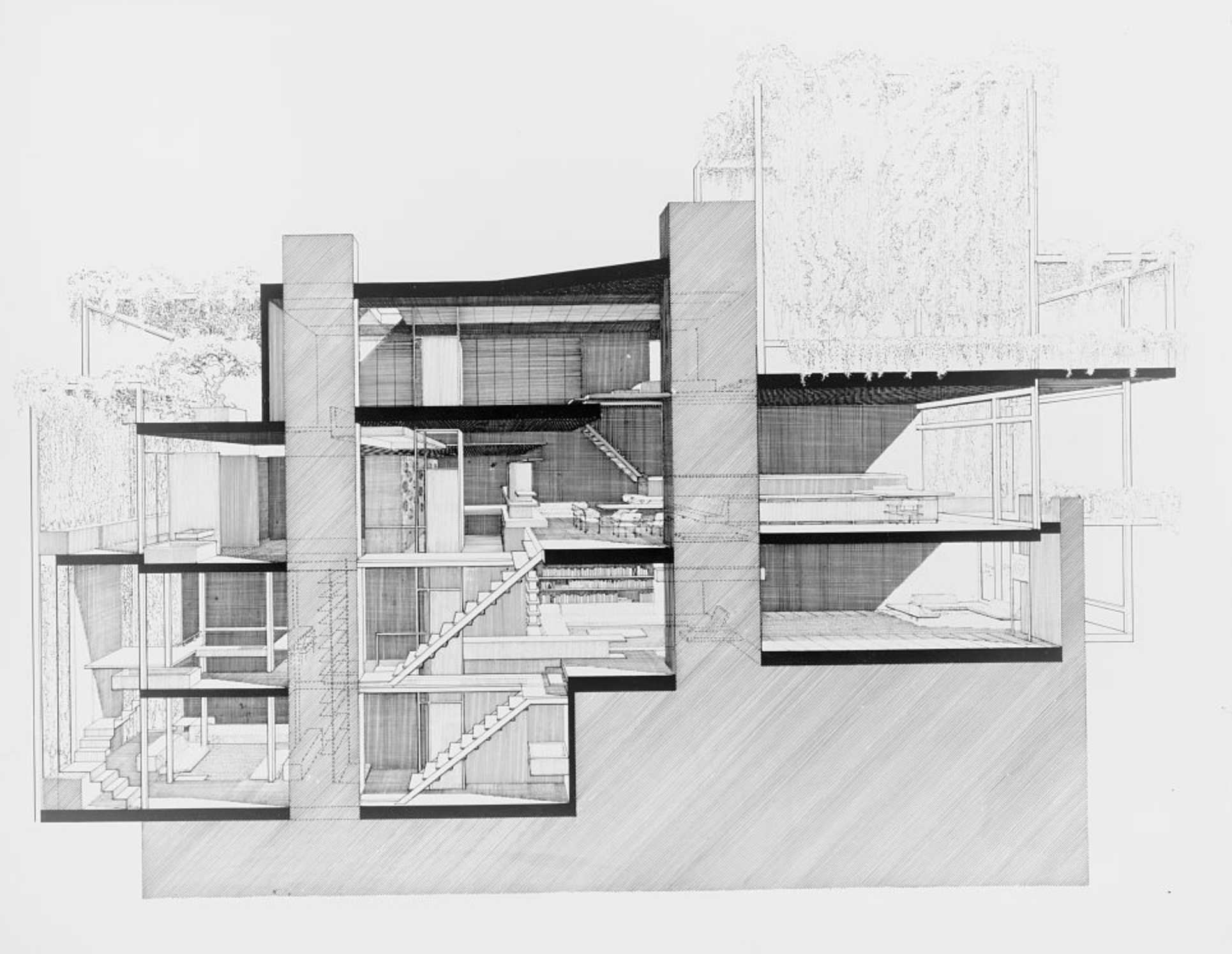

Paul Rudolph, Penthouse apartment, New York City, USA, 1965

- Equally important, when I investigate a section at a particular moment of the building (either through a lateral or longitudinal section), I simultaneously think in section and plan. Sections primarily emphasize continuous or discontinuous horizontal lines, which represent various floor levels, while diagonal lines indicate movement between floors (i.e., ground floor to first floor through ramps or stairs—the latter being shown by risers and treads). The typical superimposition of walls or columns above one another express a static principle of compression by bringing the loads down to the building’s foundations. Also, important are the inclusion in section of views and passageways expressing the size and position of windows and doors in relationship to our eyes. These spatial moments can only carry meaning when coordinated between section and plan. Sections are typically not expressive of functional relationship that are primarily expressed in plan.

Although for many seeing spatially is perceived a gift, I believe that to think and design spatially is something that can be learned and practiced with confidence. Many art forms rely on the artist’s ability to conceive three-dimensionally and render their interpretation in a two-dimensional reality. The practice of architecture is not foreign to this approach, and working in plan and section is a process between conceiving space in one’s mind, and translating a vision within a physical world.

Of course, a contemporary approach to this process enables students to work on a digital model that offers the benefit of immediately designing three-dimensionally. While I am envious of the capabilities of these new software programs, my argument remains the same: To see spatially and to think and design spatially remain two different approaches. Bob Slutzky’s lesson may be the first line of defense in thinking spatially, regardless of working with analog or digital tools.