Kahn’s poetry between wall and column. As a young architecture student, I remember being awestruck the first time a faculty member introduced me to Kahn’s question: “You say to a brick, ‘What do you want, brick?’ And brick says to you, ‘I like an arch.’ And you say to brick, ‘Look, I want one, too, but arches are expensive and I can use a concrete lintel.’ And then you say: ‘What do you think of that, brick?’ Brick says: ‘I like an arch.’”

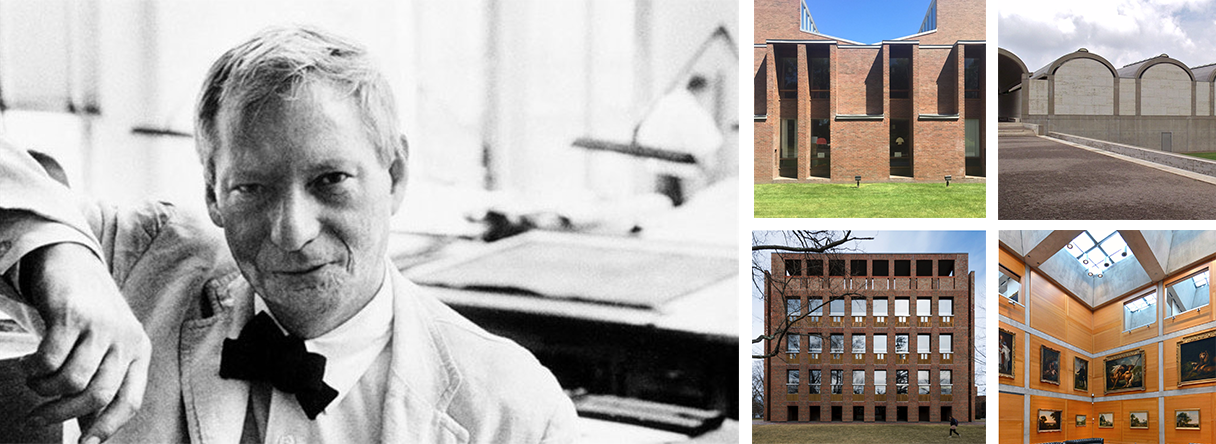

Louis I. Kahn

Kahn’s inquisitive mind was new to me, and inspiring, especially as I was in my infancy in understanding what makes building different from architecture.

Architect Louis I. Kahn (1901–1974) was not only a poet, an avid writer, scholar and teacher, he was one of the most revered American architects—admired by both the profession and architectural historians. He achieved a stature that few architects would accomplish in their lifetime, although this recognition came rather late in his professional career. At the core of Kahn’s work is his ability to translate his philosophical position into the physical world with grace and power.

While the above quote about bricks deserves a blog in its own right, in particular as it relates to those majestic brick arches at IIM’s campus in Ahmedabad, India, the below content focuses on another of Kahn’s interests: beginnings. Specifically, the idea of columns and the notion, accordingly to Kahn, that one of the greatest moments in architecture was when “the column departed from the wall.”

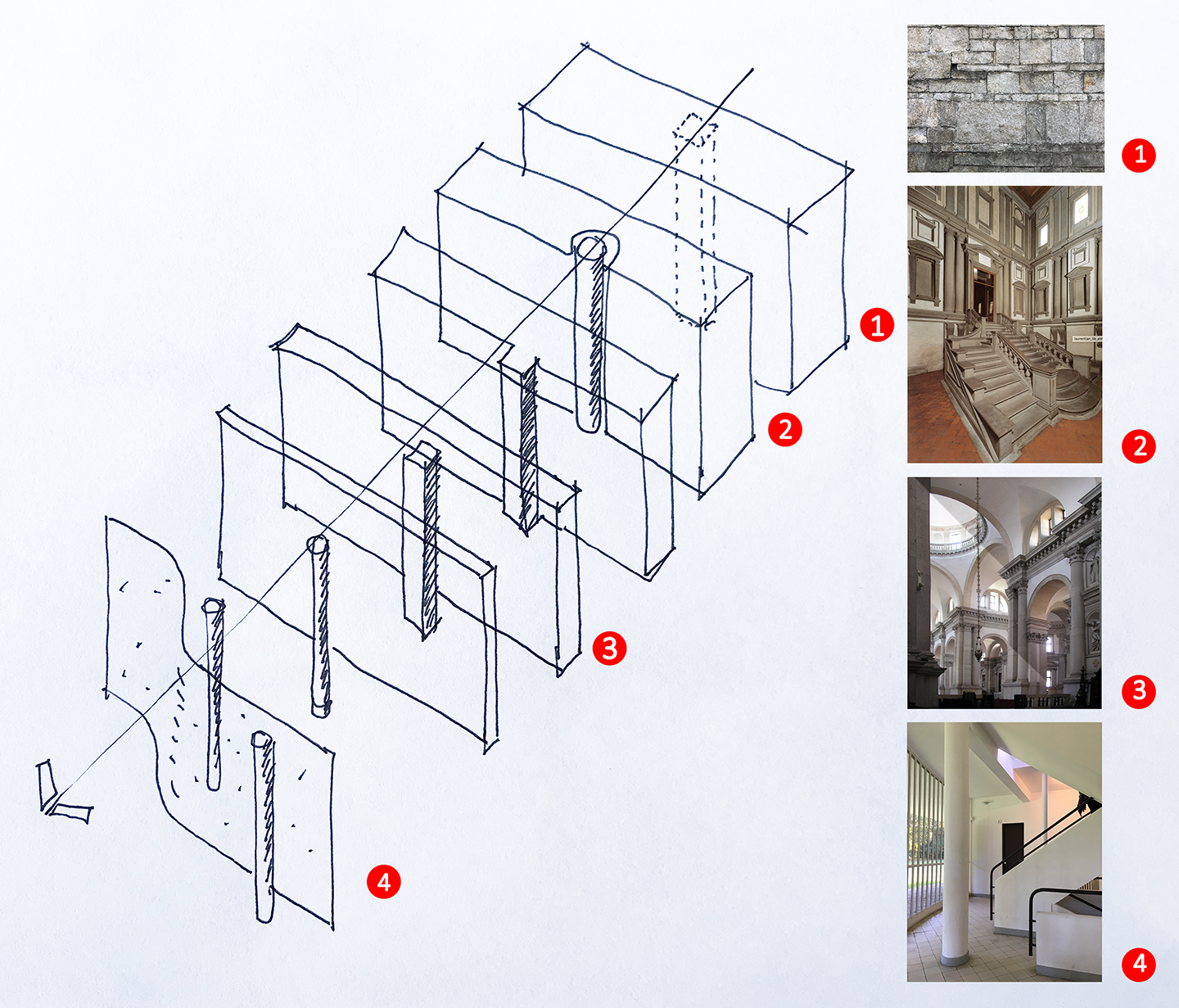

Transformation of wall to column

There is much to elucidate in the transformation of a wall to a column throughout two millennia; from a heavy structural wall to contemporary architecture where glass is the only remaining physical and non-load bearing element between inside and outside. Walls disappear, to leave columns as the bare minimum structure holding up the building. I have spent time discovering and rediscovering the relationship between walls and columns, and have identified a few examples of the column departing from the wall in the x-axis: (1) medieval wall in Switzerland, (2) the Laurentian Library vestibule of Michelangelo, in Florence, (3) the church of Santo Spirito by Filippo Brunelleschi, in Florence, and (4) Villa Savoye at Poissy by Le Corbusier (Image 2, above).

Kahn’s concept of the column departing from the wall may be stated differently; one might say that the column was always integral to the wall in its ontological meaning or state of being. This idea of his, and how he literally builds it, remains a fascination of mine. In my research, the following four masterpieces clearly exemplify Kahn’s idea:

- First Unitarian Church in Rochester, NY (1962)

- Library at Phillips Exeter Academy, NH (1971)

- Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, TX (1974)

- Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, CT (1977, finished after his death)

As a preamble to my observations, it is important to note that Kahn was not unlike many other master architects in search for the origins of architecture. He was particularly interested in Roman architecture and his oeuvre remains a testimony of his recherche patiente (a patient search) to understand and reinterpret, through contemporary forms and shapes, Roman principles within his architecture. Three of the four examples here relate to Kahn’s interest in Roman architecture.

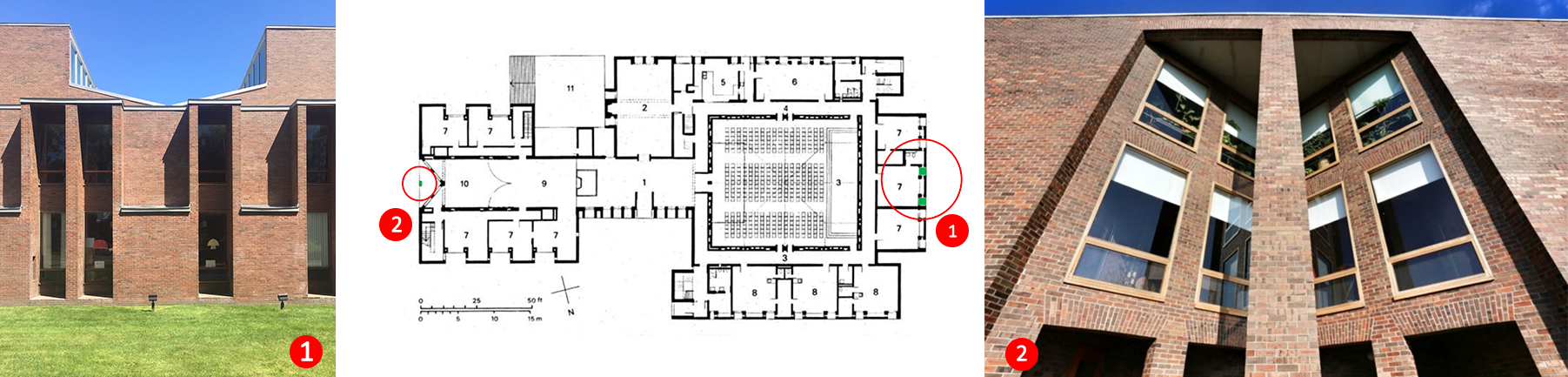

First Unitarian Church in Rochester, NY (1962)

Image 2: Google Images

In this project, two examples present Kahn’s expression of the idea of the column departing from the wall.

The first example is defined by the exterior volumes that surround the large central congregational space (Image 1). Through the creation of a series of shallow niches that bathe the inside corners of the classrooms and meeting/conference rooms, Kahn suggests, on the exterior facades, a series of narrow and elongated vertical spaces that equate to columns. This is achieved in two different ways.

- Through the expression of pier structures forming a repetitive rhythm of the façade that suggest columns, and

- By intimating the shape of a second column by the creation of a hollowed-out space between the piers and the shadows, perhaps the strongest of the images.

The second example (Image 2) is located on the east side of the complex, opposite the previous example. Again, expressed in the façade, there is an impression that the wall peels off into two diagonal secondary surfaces containing large windows, while a column emerges as the single remaining element of the former wall. This is reinforced by the expression of both edges of the wall, showing their thickness while articulating the transition from wall to two recessed walls. Magnificently expressed, the authority of the physical column becomes a central vertical structural element, one that was previously “hidden” in the wall and is now revealed to command the tectonics of the symmetrical and monumental opening.

Library at Phillips Exeter Academy, NH (1971)

Image 3: Google image of the Forum in Rome (left) and Exeter Library by Louis I. Kahn (right)

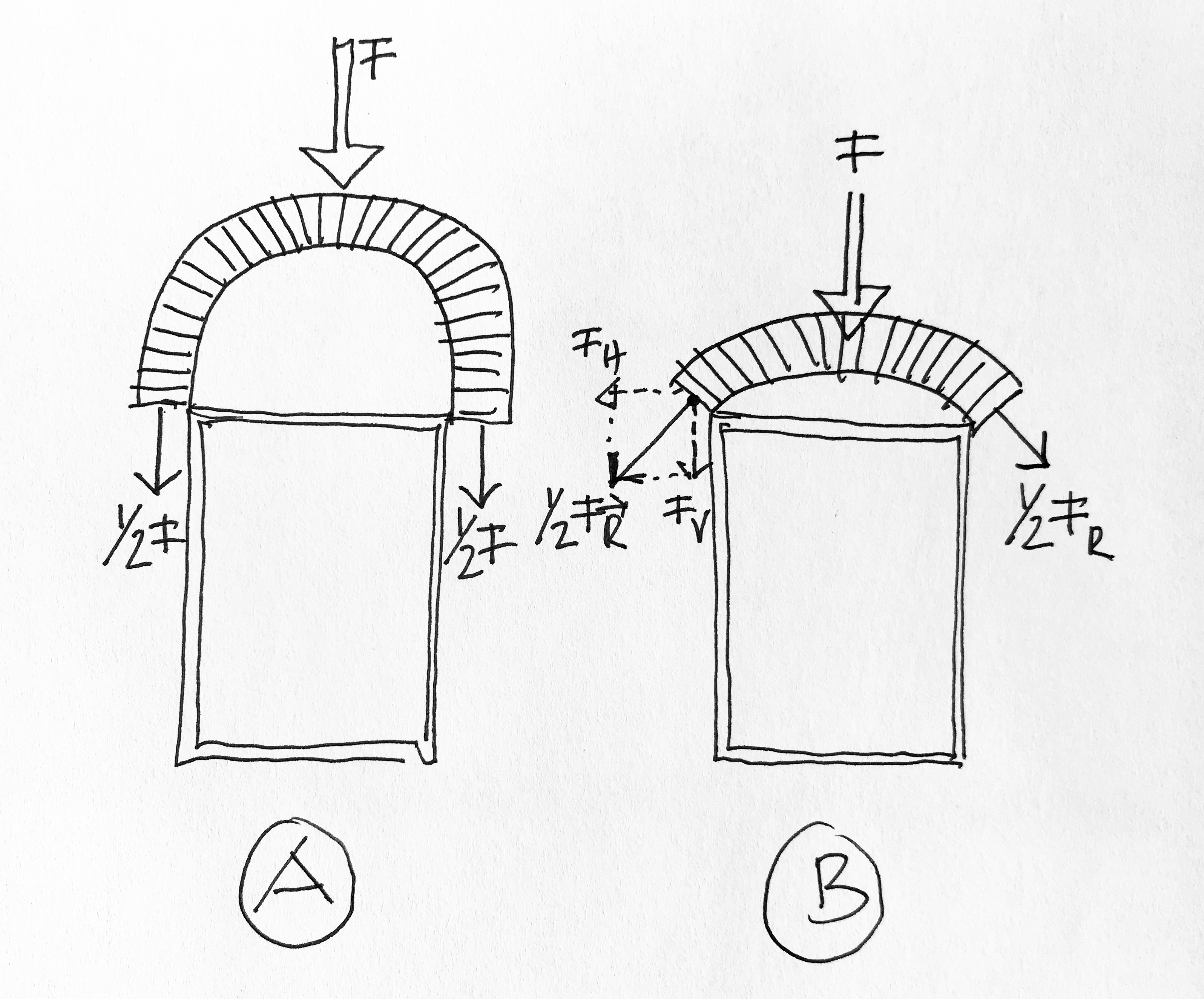

This project is perhaps the most academic example of how Kahn visually expresses the departure of the column from the wall. This is accomplished through the subtlety of Kahn’s historical understanding of how Roman architecture superimposed openings one above the other. Rather than using a lintel to span the opening (window or passageway) as was traditionally done in Greek stone architecture, ancient Roman structural know-how of brick masonry allowed architects to bridge the void with arches or vaults of various curvatures. Contrary to the use of a half circle arch (Diagram A), a shallow arch (Diagram B) has the bricks protruding at the top of either side of the opening. Of course, and without going into too much detail, we cannot omit mentioning that a true half circle versus a shallow arch behaves differently in terms of static diagrams .

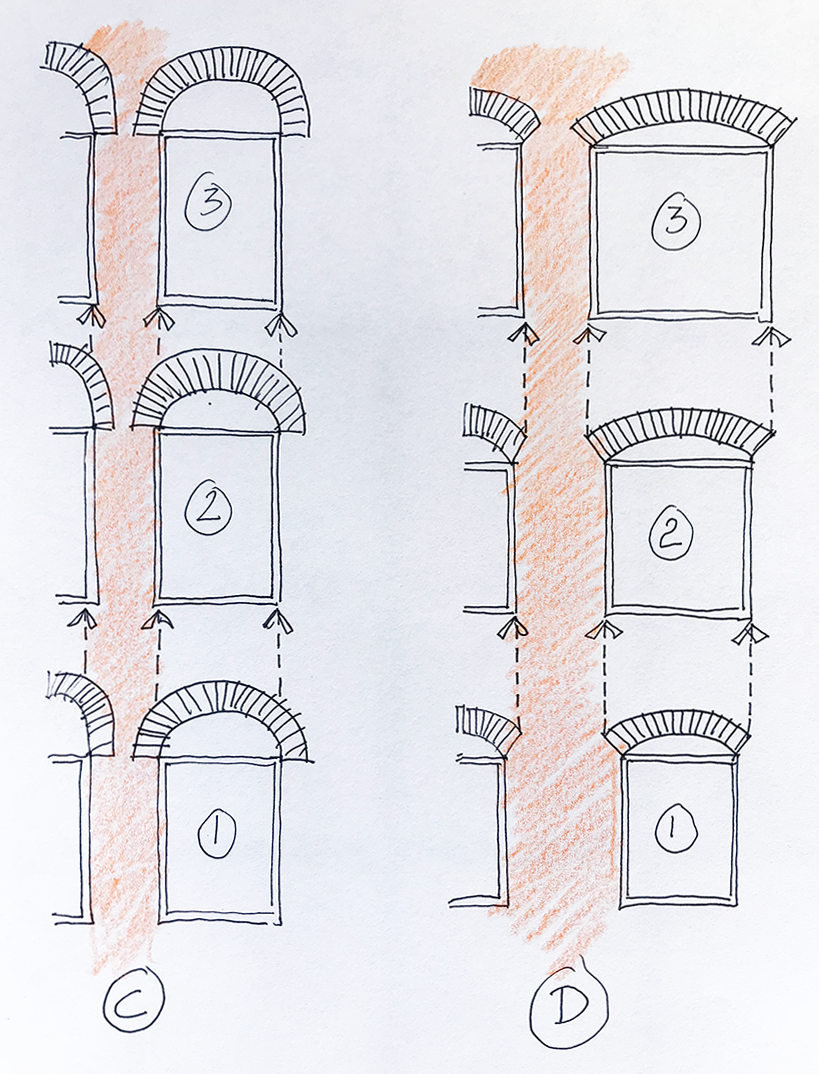

Image 4: author’s sketches between Roman arch and Kahn’s arch at Exeter Library

When Roman architects superimposed openings (Diagram C), they aligned the vertical edges of each opening (2) with the edges of the lower (1) and upper (3) voids. The genius of Kahn was to interpret 2,000 years of structural and aesthetic Roman tradition by superimposing each opening while widening them by the additional space created by the shallow arch on either side (Diagram D).

The result is that the windows become wider as they move from bottom to top. This allows the vertical brick work on either side of the openings to visually allow a “column” to emerge from the lowest point of the piers that form the base of the façade as it anchors into the ground. For me, this move has always been extraordinary in its constructive and tectonic logic, while simultaneously expressing Kahn’s idea of the “column emerging [vertically] from the wall.”

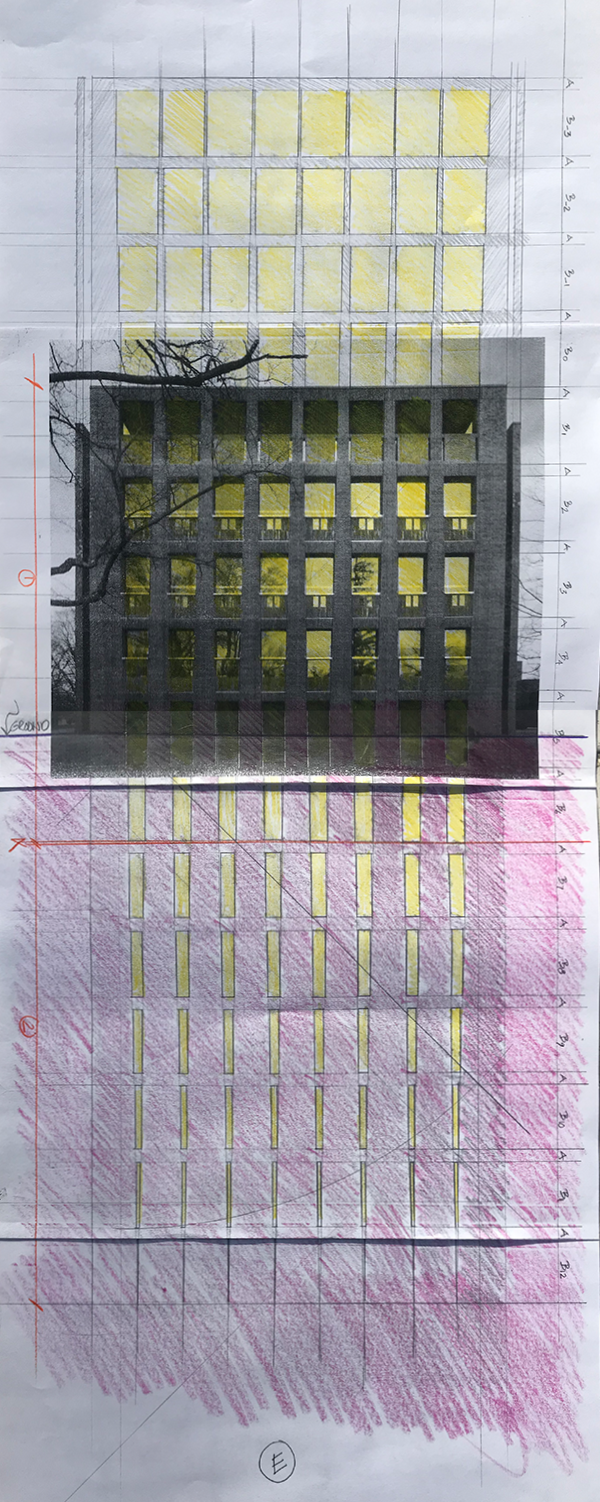

Image 5: diagram of the superimposition of Roman arches and Kahn’s interpretation at Exeter Library.

I always wondered, how would Exeter’s façade look conceptually—in accordance to the above principles—if one extended the aligned brick piers above and below the actual built façade. Without drawing immediate conclusions (Diagram E), the imagery is nevertheless compelling in its power of suggestion.

Image 6: Author’s diagram to understand Exeter Library within the larger context of a wall (bottom) and thin column (top)

Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, TX (1974)

Image 7: Google image of the interior column (left) and exterior column (right) at the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Wayne, Texas.

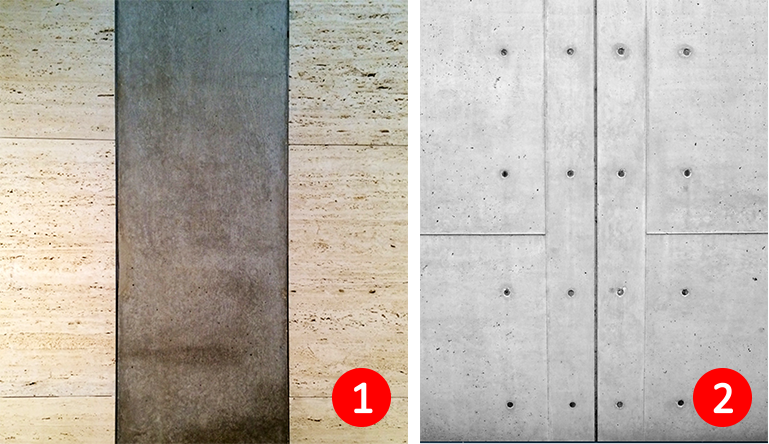

Here the columns are clearly expressed without much ambiguity. While the actual columnar structural system of the Kimbell Art Museum is clearly registered between interior and exterior non-load bearing travertine walls (Image 1), one finds another moment that subtly references back to the historical transition between column and wall (Image 2). Carefully expressed after the removal of the formwork, a column awaits its moment to depart as it partakes in Kahn’s metaphor. The tension expressed in both moments visually balances the actual column with the imprint of the column.

Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, CT (1977)

Image 8: Google images of various column positions a the Yale Center for British Art.

This final example suggests three additional interpretations of when “the column departed from the wall.” In the left-hand photograph (Image 1) the emergence of the column results in the removal of the walls on each of the four sides. Now, the singularity of the column stands proud, yet through its square (not round) shape indicates that it belongs to the intersection of the remnants of the walls.

Image 2 reveals a column as either recessing into or emerging from the wall. The wall is a non-load bearing white oak wood partition that is treated as large windows between the gallery spaces and the central inside courtyard. The warehouse type structure deviates from a normal juncture of column and beam, in that they are not resolved in the same plane, thus creating a hierarchy for the column as if it was still in its original position and not yet ready to emerge from the wall. This is further emphasized by aligning the wooden infills with the horizontal beams and not with the columns.

Image 3 is Kahn’s celebration of the column that now has not only emerged from the wall but has become both an object in space and an object that makes a space. In this instance, the column is no longer a structural element partaking in the warehouse type structure, but contains a functional element of vertical distribution, namely a stair.

Conclusion

These four projects are examples that demonstrate Kahn’s intellectual rigor and ability to render visible when “the column departed from the wall.” This remains for me one of the most magnificent architectural lessons that any student should be introduced to prior to graduation.

the information provided was very helpful. I am a college student writing a detailed research paper about Louis Kahn’s architecture. The article was just what the doctor ordered. Thank you

Dear John, I am glad that I was helpful, especially in how I believe Kahn was able to be part of a historical continuity. What aspect of Kahn are you covering if I may ask?

Beautiful analysis of Kahn’s columns. I should point out that Santo Spirito in Florence was by Brunelleschi and not Palladio. But the historical lineage progressing from the medieval wall to Corb is apt.

My greatest mistake. Just returning from Venice, Palladio was on my mind. Thanks for highlighting my error. I will make the correction promptly