Question of Pedagogy, Part 2. Rarely have I wavered from my interest in teaching the discipline of architecture, one that is historically defined as a spatial art form. But on the few occasions that I have, it was because students took their research into such innovative and compelling directions that I could only lend them my full support.

Question of Pedagogy, Part 2. Rarely have I wavered from my interest in teaching the discipline of architecture, one that is historically defined as a spatial art form. But on the few occasions that I have, it was because students took their research into such innovative and compelling directions that I could only lend them my full support.

Teaching architecture—as in translating ideas into space—is not as easy as many neophytes may imagine and I have tried to give it my utmost attention and consideration, remaining open to new ideas as well as to the principles upon which my own education rests.

My approach to teaching architecture incorporates many art forms: art, landscape architecture, history, material culture, philosophy, urban forms, vernacular architecture and even the art of cooking to name a few. In this integrative approach, for me the delight lies in the complexity of the discipline. If orchestrated to the best of the ability of the architect, he or she should interpret the client’s needs AND provide them with a model of life. Yes, this might seem a traditional point of view, but it is not often achieved with elegance and genuine commitment. Today, far too many designers create an object of visual delight. While they do this with extraordinary talent, they fail to respond to basic human needs and, in today’s climate, these necessities must be at the forefront of any project.

Interpreting social concerns through space is to balance function with spatial poetry, integrate technical and constructive components, and, if the building is to see light in physical form, it is important to integrate the critical constraints of health, safety and welfare. One important aspect to how I practice and teach architecture is understanding the program as both function and vision. For me, it is a necessary point of departure to anchor my journey as I think about how my contributions will respond to the client’s needs, yet partake in what I consider the art of building.

While these responsibilities are paramount, I have also discovered alternative approaches to the making of architecture that differ from the practice of architecture. This is true when a function is not the immediate impetuous to create space, especially in academia when projects may be exclusively for didactic purposes.

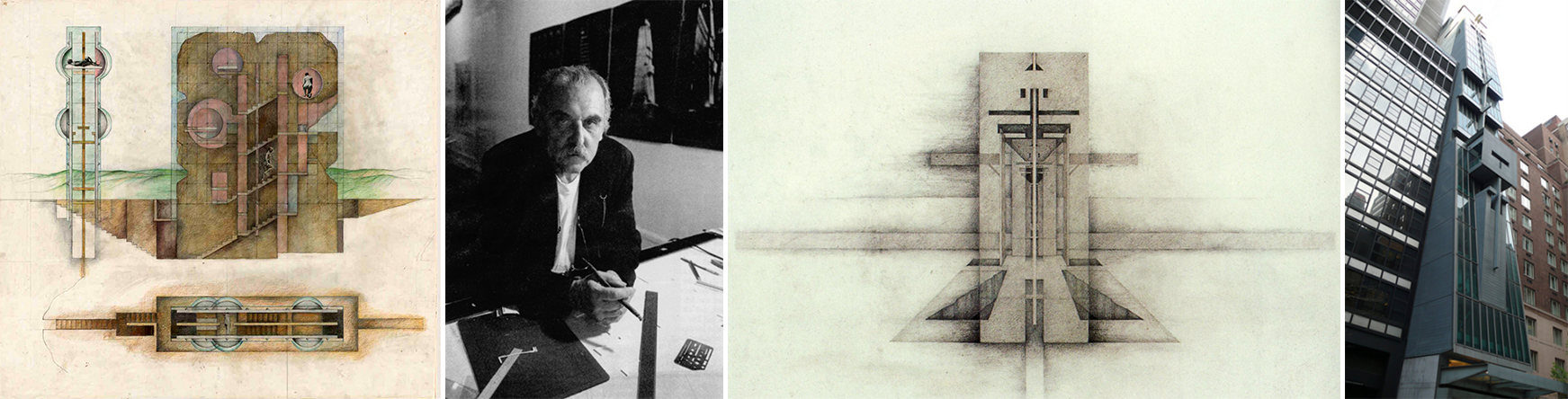

Google Images: Conceptual project, competition and built work by Raimund Abraham

Google Images: Conceptual project, competition and built work by Raimund Abraham

During my studies at Cooper Union, the studio project conducted under Professor Raimund Abraham (1933-2010) introduced me to alternative design processes. Ever since, this type of project has intrigued me with their tectonic power and ability to create tangible and highly meaningful outcomes. A key figure in my trilogy of mentors, Raimund’s architectural language remains so powerful, idealistic, and visionary, and above all, non-negotiable in what he thought architecture to mean whether in his conceptual projects, competitions, or built work.

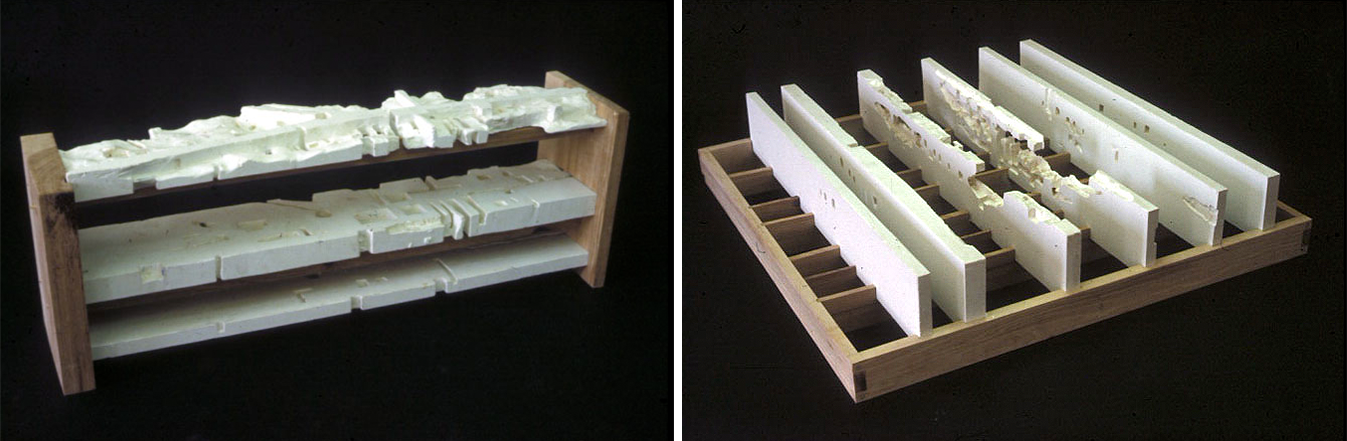

Studio project Image 1: student’s study models expressing gravity horizontally and vertically (UK 1988) author’s collection

Image 1: student’s study models expressing gravity horizontally and vertically (UK 1988) author’s collection

I remained so fascinated with Raimund’s approach to architecture, that when I joined the faculty at the University of Kentucky—a year after my studies ended at Cooper—I incorporated my own version of what I had learned. Mentoring sophomores is to teach fundamentals in the discipline of architecture, while building on strong visual and design principles acquired in first year. When I created my second year studio assignments the pedagogy was simple.

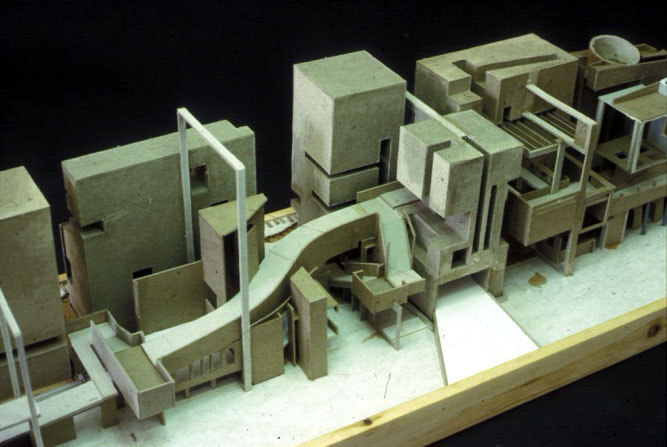

The project presented here was defined as basic architectural studies, and the impetus to challenge students was to avoid any traditional function to generate a building (house, theatre, museum, etc.). Emphasizing the tectonics would drive the project and ultimately suggest a function; a strategy that Raimund favored as a way to start a studio project. Providing a prompt to get the students’ curiosity moving in the right direction, the program called for them to express the universality of gravity in visual form.

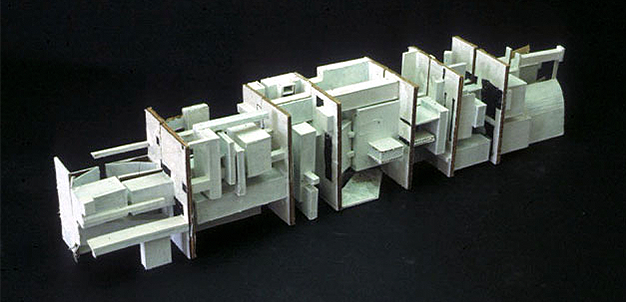

Image 2: intermediate student study model combining the vertical and horizontal sketch models (UK 1988) author’s collection

Image 2: intermediate student study model combining the vertical and horizontal sketch models (UK 1988) author’s collection

Working with a number of planes, students were to fabricate in model form their understanding of gravity as suggested in either a vertical, horizontal or suspended condition. In addition, they were to think about the physicality of the material(s) involved in their plane(s) through operations of subtraction, addition, erosion, fragmenting, etc. (above image 1). They were also welcome to introduce foreign elements and colors that would alter the surface and depth of their plane(s). As a required deliverable, students were to introduce architectural features such as entrance, circulation, openings, and structure, suggesting a first attempt at translating their studies into the realm of architecture (above image 2).

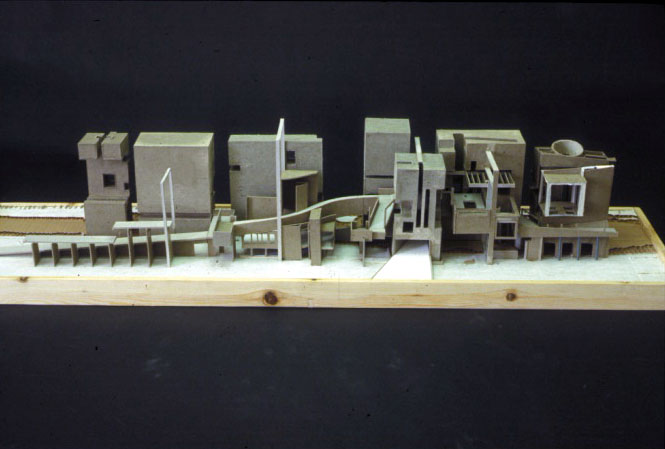

Image 3: student Final model (UK 1988) author’s collection

Image 3: student Final model (UK 1988) author’s collection

While the final proposals remained so ever visually present as an object (above image 3 and below image 4), students had to allow their model—which was equally developed in plan and section—to suggest function and program. In one student’s project (see above and below images), this process resulted in proposing a dense urban housing complex of seven units. Now that architectural meaning enabled a further development of the project, the student faced the challenge of how to create an urban block encompassing a variety of dwellings with their adjacent private and public open extensions.

At the end of this exercise, the project was an opportunity to learn about tectonics and how they interact with each other, along with the first ideas of an architectural promenade. Above all, they learned how to create a process where parallel concerns could give birth to a mundane program: in this case urban housing, which defined the locus of architecture as an urban phenomenon.

Image 4: detail of student final model (UK 1988) author’s collection

Image 4: detail of student final model (UK 1988) author’s collection

Image 5: design studio atmosphere with models at the forefront. Featured student is not the author of the described projects (author’s collection)

Image 5: design studio atmosphere with models at the forefront. Featured student is not the author of the described projects (author’s collection)

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy. Part 1

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy. Part 2

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy. Part 3

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy. Part 4

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy. Part 5

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy. Part 6

Architectural Education: The nature of IDEAS