The ritual of a formal and on-going assessment is something educators tend not to favor, especially since the perception is that it takes away from our commitment to teaching, from our love of teaching. And yet, in architecture programs, assessment is tacitly done on a weekly basis, especially through discussions of student design work. These often-subjective evaluations are based on the student’s progress, encompassing discussions, Aristotelian critiques, and suggested paths to improve and overcome any stumbling blocks in order to have them make substantial improvements.

The ritual of a formal and on-going assessment is something educators tend not to favor, especially since the perception is that it takes away from our commitment to teaching, from our love of teaching. And yet, in architecture programs, assessment is tacitly done on a weekly basis, especially through discussions of student design work. These often-subjective evaluations are based on the student’s progress, encompassing discussions, Aristotelian critiques, and suggested paths to improve and overcome any stumbling blocks in order to have them make substantial improvements.

The teaching and practice of architecture

For a studio-based faculty in architecture, these observations may seem self-evident. But what I am suggesting here is that we conduct robust self-evaluation on the why, how, and what we teach our students on a regular basis, or at least once every academic cycle. I believe that a contemporary education is only as good as its embrace of change and how it manages to advance the curriculum through constant, informed, and often discrete adjustments, that over the years collectively move the curriculum to a next level of excellence. Debate over evaluation typically focuses on the primacy—and regrettably on a faculty’s privacy—of the notion of pedagogy and ensuing teaching objectives, notwithstanding the real focus of the educator’s mission, which carries the ultimate question: What do our students learn?

The practice of architecture may be seen by some faculty as an often-disturbing real world of professional practice—a position that fails to be acknowledged despite that an architectural degree is first and foremost a professional degree. This position is perhaps because the Bachelor of Architecture degree in the United States is followed by a three-year Architectural Experience Program (AXP), formerly called Internship Development Program (IDP), which is legislated by The National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB), and leads towards licensure and the right to practice as an architect in the United States.

Registration upon graduation

In Europe, and in many other countries around the world, architecture education is sanctioned by a degree where you are registered upon graduation. For me, this holistic approach makes common sense as the integration of academic pursuit and professional accountability is seen as a seamless endeavor. Currently in America, this path is gaining traction and is called Integrated Path to Architectural Licensure (IPAL). “…Since 2015, 26 NAAB [American National Architectural Accrediting Board] accredited programs at 21 schools across the country have established an IPAL option, providing their students with an education that connects to real-world practice [aka, learn-by-doing, hands-on, and experiential learning] while shortening their time to licensure and expanding their career opportunities.”

Typically, architecture programs that offer first professional degrees (B.Arch. or/and an M.Arch.) conduct targeted and robust assessments when, every eight years, they need to prepare and showcase the program in order to meet the minimum requirements defined by NAAB for accreditation. During this cycle, which spans a year prior to the on-campus accrediting visiting team, the program under review is in full gear, often creating trepidation and apprehension. Faculty collectively write the Architecture Program Report (APR), gather student artifacts of the past year, and present synthetically the efforts of faculty to demonstrate that student work meets the minimum criteria defined by the NAAB.

Accompanying these heroic and meticulous efforts, exhibitions punctuate the school’s public spaces, and a secure room is identified where private discussions among team members unfold prior to offering findings at the end of the three-day visit—typically a brief report based on areas of program strengths and causes of concern.

Realistic Vision

Having been in academia for over 30 years, I will confess that beyond minor adjustments to certain program areas there is generally jubilation around the renewal of accreditation. I have fortunately been associated with institutions that were never in jeopardy, and have also served as a team member or chair of visiting accreditation visits for the Canadian Architectural Certification Board (CACB) with positive outcomes. After these positive reports, in all cases, faculty almost all promptly return to their daily lives of teaching, research, and service without further discussion about potential curriculum improvements.

At my current institution, we have welcomed an invigorated new leadership team, and are focusing on epistemological questions about our teaching responsibilities. Recently, I attended a faculty meeting where the moderator presented an ambitious plan—I have rarely seen such a push to think holistically about our architecture program—to rethink the legacy, inheritance, lineage of our past pedagogical practices, curriculum, and teaching ambitions, while understanding our present and the potential of the future.

For those that favor sarcasm, this exercise—taken as a totality—seems futile in its scale, but for me, it is a moment calling for introspection; one that was initially triggered by the paradigmatic shift of moving from a face-to-face environment to an online communication/teaching method, in our case Zoom. Ironically, for all skeptical and die-hard naysayers who never believed that an architectural studio could be taught successfully on line, this new mode of exchange between faculty and students has opened up, for me, robust and rich opportunities to requestion preconceptions regarding the locus of architectural classes and the ancestral traditions between teaching and learning.

At our school, we favor educational models that allow students to attain knowledge in anticipation of becoming architects. These models include those of the Greek philosophers Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle, along with some closer to us, the Bauhaus and Jean Piaget, for example, and for those who favor an anthroposophical approach the Waldorf curriculum founded by Rudolf Steiner, to name but a few.

Of course, within this rich context, each faculty comes to teaching—either as a novice or seasoned educator—with a set of principles that evolved from their own educational experiences, complemented by rites of passage gained through positions at different institutions. This is what makes the richness of teaching, and certainly our students are the prime beneficiaries of this complex web of opinions, experiences, and often dogmatic approaches.

When asked to provide some thoughts on the school and, in particular, how each faculty sees their role as an educator, I assembled some points regarding fundamentals that I believe underlie my teaching responsibilities, accompanied by two diagrams that explicate the manner in which I teach any course (studio, seminar, lecture).

Background

- The responsibility of the architecture faculty is to impart to their students a contemporary architectural education based on a holistic approach to the education of an architect.

- It is agreed upon that students enrolled in the undergraduate architecture program seek access to a Bachelor of Architecture degree.

- The locus of our teaching takes place in a context where faculty teaching is measured against student self-inquiry. The primacy of the architecture program is to maintain the architectural thesis as a spatial endeavor, in which the project remains central to all activities.

- The nomenclature of a studio versus a laboratory is negligible based on the understanding that seasoned faculty members often take different roles at different moments during the course of a student’s tenure.

- Academic freedom is paramount in interpreting accepted institutional learning outcomes, program outcomes, and project outcomes, and this within an ever growing understanding that interdisciplinarity is central to a contemporary educational approach.

- It is imperative that faculty’s teaching is measured primarily against student learning outcomes.

Diagrams

The following two diagrams (1 and 2) approximate the context in which I direct my role as a faculty colleague and educator. Image 1: Diagram 1: (author’s collection)

Image 1: Diagram 1: (author’s collection)

Diagram 1

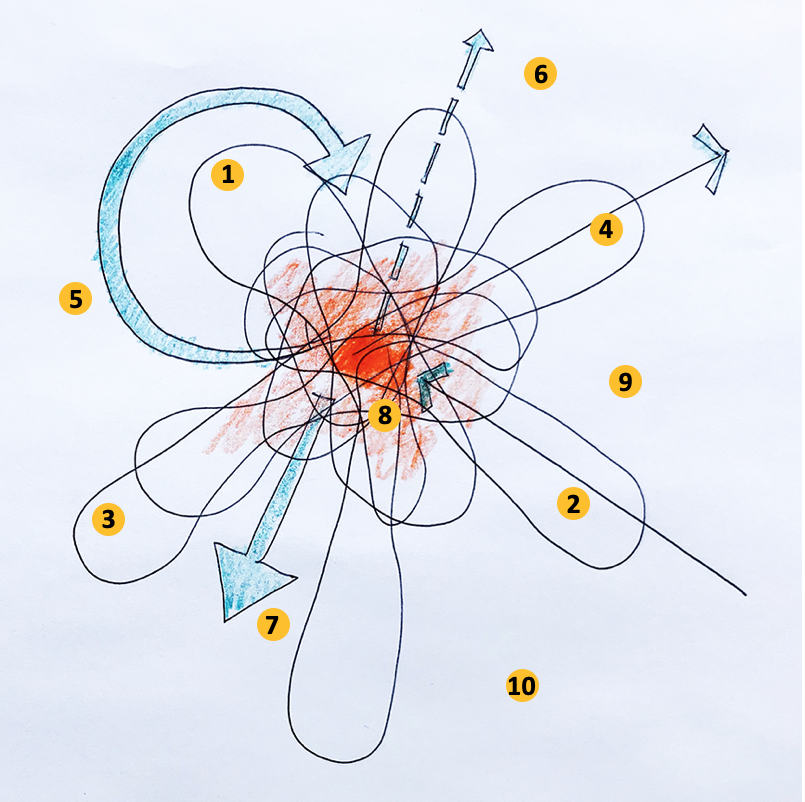

The above diagram (Image 1, above) describes an amorphous shape formed by multiple lines that depart from a center and extend in various directions with different lengths and intensities. These lines overlap each other and return to a focal point that might be called architecture (in orange), to re-emerge in various sizes.

The intention of the diagram is to showcase the various connections that architecture has with 1. art, 2. aesthetics, 3. context, 4. economics, 5. materiality, 6. medicine, 7. politics, 7. structure, 9. sustainability, race, and equity, and 10. technology to name a few, all while emphasizing that each of those links may take a hierarchical role within the overall connections that architecture has through time and culture. Suggested arrows (in blue) reinforce relationships toward and within the diagram, and potential new and unforeseen associations.

Diagram 2: (author’s collection)

Diagram 2: (author’s collection)

Diagram 2

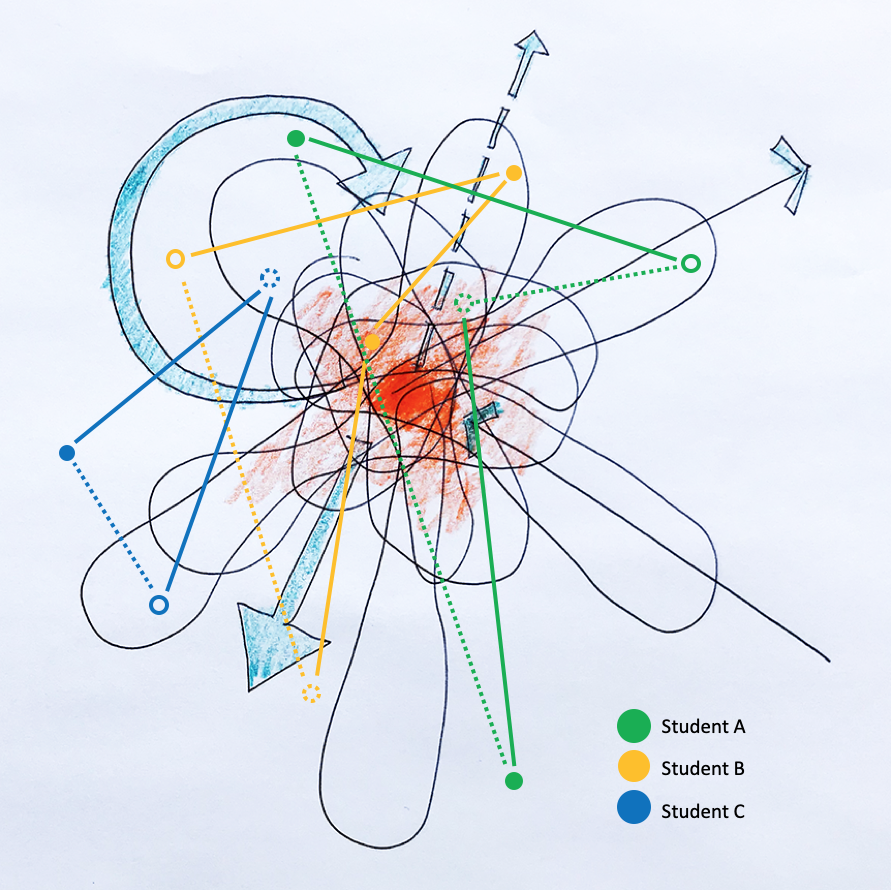

Building on diagram 1, the locus of student learning is to develop a self-awareness based on a series of interests along the historical and theoretical dimensions involved in the discipline of architecture. Balancing teaching objectives and directed learning with the promotion of an autobiographical learning is key for students to create, develop, and leverage new knowledge.

In this example (Image 2. Above), three students (A , B, and C) develop a personalized set of points of interest, connecting them in order to develop their ability and understanding of key fundamental components of the discipline of architecture. For example, student A may develop affinities with issues surrounding construction, materiality, detailing and skin facades; perhaps a portfolio of interest that could gain traction with a minor in construction management. Student B is interested in issues of equity, gender, race and urbanism, while student C focuses on issues of sustainability, landscape architecture and contextualism.

The success of this dialectic between teaching and learning offers each student the ability to investigate a world of their own, always accompanied by key concepts integral to the field of architecture and always based on the interconnectivity of existing and new knowledge.

Perhaps, along with many of my colleagues, I long for what we may call Towards a New Pedagogy.

Other blogs of interest

Some thoughts on teaching. Part 2

Architectural Education: First steps in a student’s design process