John Hejduk and Cooper Union. Ask any architect, faculty member, student, or layperson to define architecture, and you will get countless individual responses. I am always astonished by the diversity of the answers, in particular with laypeople who have strong impressions often based on personal memories and stories about family members who are architects. However diverse all these conversations are, I have come to appreciate each of the answers. Collectively, they renew my love of architecture.

As a student at the Swiss Ecole Polytechnique Féderale de Lausanne (EPFL), I remember learning early on about Le Corbusier’s (1887–1965) statement that: “Architecture is the masterly, correct, and magnificent play of masses brought together in light. Our eyes are made to see forms in light: light and shade reveal these forms.” This famous proclamation resonated like a mantra during my student years, and Le Corbusier’s insistence on the intangibility of light, made architecture even more poetic and increased my desire to learn. As I honed my skills over the years, and ventured into practicing and teaching architecture, my perspective on the question of what is architecture expanded to become a pleasant lifelong conundrum.

Building on the diversity of meanings, there seem to be in Western culture, from antiquity to today, ways of defining architecture that encompass a range of abilities to:

- Produce buildings as a service provider

- Portray construction through its tectonic expression

- Create an architecture of objects

- Legitimize architecture as an autonomous discipline with its own vocabulary, grammar, and syntax

- Expose cultural values by communicating meaning

- Facilitate the sharing of knowledge

- Reflect political expressions of social practice

Of course, any perceived boundaries between the above perspectives are more malleable than their meanings suggest, especially when seen through a faculty’s lens as part of an institutional and programmatical identity.

The EPFL

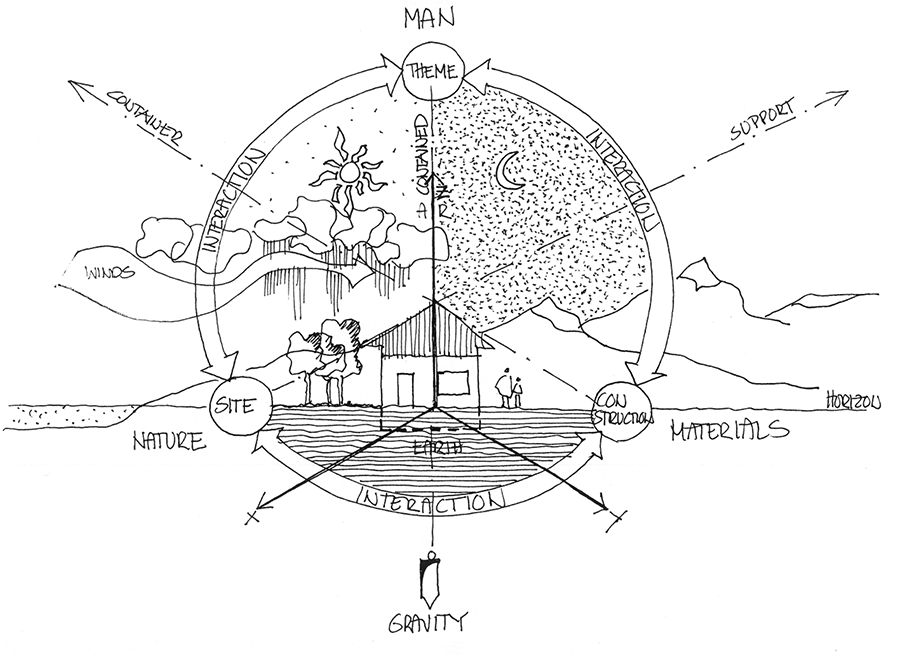

While I have seen many thought-provoking diagrams on the nature of architecture, the particularity of the diagram below displays fundamental concerns that shape man’s physical environment. The tripartite division formed around the circle expresses the interconnectivity of a design process that extends the basic functional and utilitarian needs of daily human activities. This created environment balances economic, social, and emotional needs, as well as cultural aspirations that must negotiate the qualitative with the quantitative.

This holistic interpretation of architecture based on vernacular architecture was presented to us as students during our first analysis project. Within the context of learning about indigenous buildings, faculty stressed the importance of societal organization and hierarchies (space making), and the rights of its members to enable possible and desirable relationships between groups (place making). Specific site conditions, and to a larger degree everything that embraced the meaning of context, were chosen for each function and ritual in order to enhance the individual and the community at large.

In this instance, architecture was taught as being able to translate certain ideals and reflect the thoughtful integration of those aspirations within expressive, plastic, and symbolic dimensions. As a result, architecture was both an aesthetic and functional environment created within the trilogy of Man, Nature, and Materials.

This unfolds in space (physical and cultural); in time (history and theory); and in materiality (technical and cultural). The cycle of architecture in this diagram became primordial, diachronic, and ephemeral in each of my subsequent design projects. Since then, the word ephemeral has always intrigued me in architecture, and this despite my desire to express a sense of permanence in the act of building. It was only during my studies in the United States that the meaning of ephemeral became more comprehensible and tangible.

Cooper Union

During my studies in New York City at The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art (fondly called among students Cooper Union or simply Cooper), I was presented with another model that brought my understanding of architecture to a new level: less pragmatic, more poetic, and closer to those metaphysical questions related to our existence. The furthering of knowledge brought me to Cooper, and my tenure there was nothing less than extraordinary.

One of a small cohort of three international exchange students, I had my heart set on studying under Professor Raimund Abraham (1933-2010), yet, curious and intrigued by the fame of Dean John Hejduk (1929-2000), I attended the introduction to his thesis class. The experience left me in awe, with an unreserved respect toward this amazing pedagogue.

At that time, slides were still common in presenting course material, and in a semi-darkened room tucked at the end of a long white corridor on the fourth floor of the Foundation Building, John presented to a devoted group of thesis students (yes, John had his unconditional followers), an image of Bacchus, the Roman god of wine. The image depicted a marble sculpture created from the genius of Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564). There was no need to reflect on the greatness of the work of art in front of us. It was art in its most intense beauty.

In his typical and deep Bronx accent, John asked us what we saw on the screen. Between timid suggestions and authoritative proclamations, our answers were far from the poetry that was to unfold in front of our eyes. The same question was posed once again, but followed this time by total silence. The emptiness of our answers filled the room with a sense of incredible weight. After what seemed an eternity, John stood up, and with a gentleness never seen before from a professor, asked: “don’t you see him B R E A T H E.” This was followed by the year’s pedagogical statement: “This is what we will learn, how to infuse life into inert material.” The projector was turned off, and John left the room swiftly with no further explanation.

That day, there was no return for me. With a renewed sense that architecture might find its locus between mind and matter, I started my yearlong studio with Raimund Abraham and learned from him that architecture started at the horizon, a space between earth and sky that reflects a profound ontological approach to design.

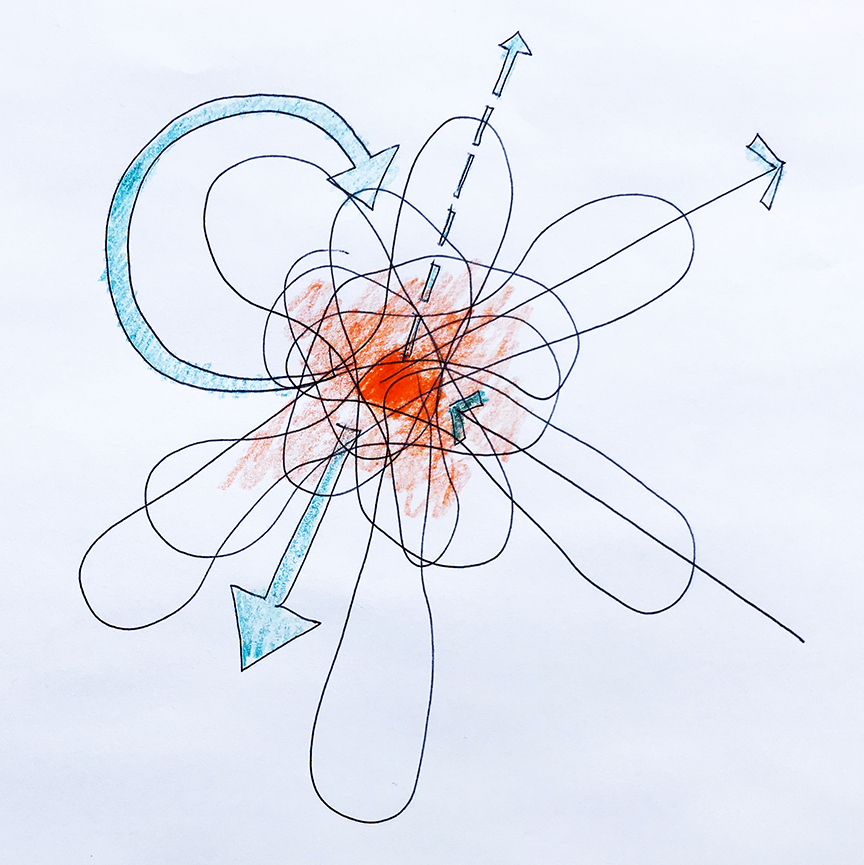

The rest is history and the spectrum of what might define architecture would become a lifelong endeavor. To this day, I remain hesitant to make any proclamations on the specificities of what is architecture, but when asked by students how I would define my discipline, I—without hesitation—draw my own diagram suggesting the connections that architecture continues to be involved with, while always being mindful to never define what architecture is (see below image).

The diagram describes an amorphous shape formed by multiples lines that depart from a center and extend in various directions with different lengths and intensities. These lines overlap each other and return to a focal point that might be architecture (in orange), to emerge on the other side in various sizes.

The intention of the diagram is to showcase the various connections that architecture has with art, aesthetics, context, economic, materiality, medicine, politics, structure, sustainability, and technology to name a few, all while emphasizing that each of those links may take a hierarchical role within the overall connections that architecture has through time and culture. Suggested arrows (in blue) reinforce relationships toward and within the diagram, and potential new and unforeseen associations.

Conclusion

For me, the meaning of architecture continues to negotiate its place among those autobiographical experiences from my studies at the EPFL, the I.A.U.S, and Cooper Union, from practice to teaching and researching architecture. What I know and believe, is that what architecture may be, should remain a vision, a vision that always ends up being an uncompleted project; one that is unfinished and handed on to a new generation to pursue and interpret. As with my own experience, I have inherited from my professors a vision of architecture that I pursued, modified, and finally made my own, and yet one day I will need to hand it to students and colleagues…