Question of Pedagogy, Part 6. During my over thirty years in architectural education, I have taught at every undergraduate level, always with a specific focus on design studios, and with punctual forays into graduate instruction both in Switzerland and in the US.

Question of Pedagogy, Part 6. During my over thirty years in architectural education, I have taught at every undergraduate level, always with a specific focus on design studios, and with punctual forays into graduate instruction both in Switzerland and in the US.

Because of my interest in imparting fundamentals about space making and the need to develop a robust creative process, my predilection is for teaching second year undergraduates. Throughout all of the years of my commitment to helping students find design excellence, I have been equally committed to assisting them to find their own voices as architects. But what does this mean?

The EFPL

During my studies in Lausanne, Switzerland at the EPFL, I learned about skill building as part of the need to achieve proficiency in sketching and hand drafting—digital media was nonexistent in the early 1980s. Importantly, faculty integrated study of precedence which led us as students to acquire a design language as we progressed. This was not meant to be exceptional, beyond offering a rigorous Swiss polytechnic education built on the expertise of seasoned faculty. Each of my professors showed passion for teaching, and, most importantly as they were usually part of a professional office setting that produced innovative architectural work, our creative endeavors emulated the practice of architecture. Even in hindsight, there was nothing wrong with this tradition, and the relationships we experienced between faculty and students appears even more important in today’s academic world.

I still admire these professors who instilled in me a solid architecture background which included a design literacy that enabled me to successfully complete a number of built projects in America immediately upon graduation. However, as I look back, I never had to address the question of what it meant to find my voice. I knew about the importance of finding the calling for a project, but rarely was provoked to see my contributions as a fundamental question of authorship. In other words, an expression of an inner voice.

A traditional pedagogy

We were taught to address issues at hand (the project) and did not think about the question of a personal voice as essential to becoming an architect. Undeniably this question was present in the minds of faculty but within a Swiss educational system it was never directly addressed with students. Perhaps simply because of the idea that the nature of an architect’s role in society should be more anonymous and discrete. Design studio briefs were based on a set of processes that typically simulated professional office standards, all with the high expectations that focused on best design practices.

As architecture was considered to be part of the real world, consideration of site, function, and program, as well as construction and detailing, were integral because of a deep respect for the user’s perspective. Appreciation for our art form was drilled into our design process. We were taught to bring value to a client’s needs; never to fully give them what they thought they wanted, but always respond through a spatial interpretation of their desires.

While faculty enticed us to explore the program brief in a poetic way, our design project always carried a sense that architecture was a matter of construction. Retrospectively, for me this approach remains one of the fundamental identities regarding notions of permanence in architecture. Excellence in construction associated with innovative spatial conditions is central to the continued quality of Swiss architecture and is an idea that I integrate in my professional practice and teaching.

In today’s academic climate where nurturing students is often favored to the exclusion of imparting knowledge (fundamental and common-sense disciplinary knowledge transmitted from faculty to student) it seems that current trends let students “find their way” in design, and this by investigating what they think is of interest to them. Nurturing students should never become dogmatic and always permit an eclectic mix between a student’s welcome naivete balanced with the faculty’s didactic input.

If this balance is retained, my own education may still seem relevant with its focus on learning basic architectural principles. During my studies we were taught to rely on characteristic skills and techniques, all tacitly understood as essential to formulating creative ideas. If used without discernment, these principles would rapidly end up creating buildings rather than desirable works of architecture. As students, we believed that the acquisition of tools and skills enabled better design thinking, and at my alma mater, this was practiced through project types. Through this pedagogy, we became seasoned architects in the best sense of the word.

My early career as an educator

At the time of my studies at the EPFL we were never given abstract projects, thus our curiosity to seek non-polytechnic learning opportunities. We envied paths toward creativity espoused at other places, and looked towards Anglo-Saxon educational systems such as the Architectural Association (AA), the I.A.U.S, and The Cooper Union. I mention these three institutions because in the early eighties they stood apart from the Ivy League schools whose pedagogy promoted excellence, yet retained the modernist influences of European masters who had immigrated to America (Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe and Josep Lluís Sert) or had visited the New World (such as Adolf Loos between 1893-96, and Le Corbusier in 1935). The tenet of a modernism that was distilled to a revised functionalism was not what interested us as students. Switzerland had already embarked on a progressive understanding of architecture as territory (i.e., Ticinese movement), thus we were looking for a more artistic approach to design projects.

As students we insisted that the tradition at the EPFL—which had a solid footing among leading architecture programs—needed to be questioned and we desired a generation of faculty who would formulate new design directions. In response, college leadership offered a robust roster of guest professors (Colquhoun, Frampton, Gregotti, Huet, Moneo, Nicolin, and Siza), giving students the opportunity to learn a new way of design thinking from non-Swiss architects. For me, exposure to the painter Robert Slutzky was an epiphany.

Bob brought a breath of fresh air to the classroom and shared The Cooper Union approach to design with us, one which he called: A pedagogy of form.

“…the program tends to emphasize the visual aesthetics of architecture over other more pragmatic and technical approaches. This attitude, shared by most of the faculty, is one that is based on a belief in paradigmatic creation, that is, in the pedagogical use of exemplary or abstract problems, which however removed from real implementation or function, develops a heightened sense of consistency, a framework for inventiveness. The underlying assumption is that only through an awareness of such formal and extra-formal issues, and a commensurate skill in achieving them, can any meaningful architecture emerge.”[1]

Towards a new pedagogy, a reversal of heart!

During my early teaching career, I had the opportunity to return to Lausanne as a teaching assistant. Cognizant of my strong Swiss background, which was partnered with a new pleasure of designing based on an Anglo-Saxon model, I co-authored a design brief for master students. It focused on process and was very different from the projects offered at that time at the EPFL. In requesting this proposal, my former first-year professor was promoting a different line of inquiry, one which set him apart from his colleagues’ functional teaching approaches.

Along with my friend and fellow teaching assistant, Philippe de Almeida, we explored the following question: Can a meaningful architecture be created without a program, without functions, and exist solely as a manifestation of a student’s inner voice? Our approach was met by other faculty with suspicion and seldom with enthusiasm, thus the need for us to be successful in our ambitions.

To anchor the process (students did sign up for this studio but never really knew what they were to expect beyond an enticing project description), we made a concession by including a contentious urban site in Lausanne from which the students were to carefully read and interpret metaphorically the assigned context, and then develop a project.

I will admit that while we were fully on board with the proposed design brief, the results took another direction. Avoiding the design ideals of simplicity through a Swiss outlook (i.e., an earnestness in form reflecting a protestant moral spirit), the resulting designs seemed formally garrulous and ostentatious, yet the ideas were rich, progressive, and provocative. A ying and yang that we had not expected at the outset of the exercise.

University of Kentucky

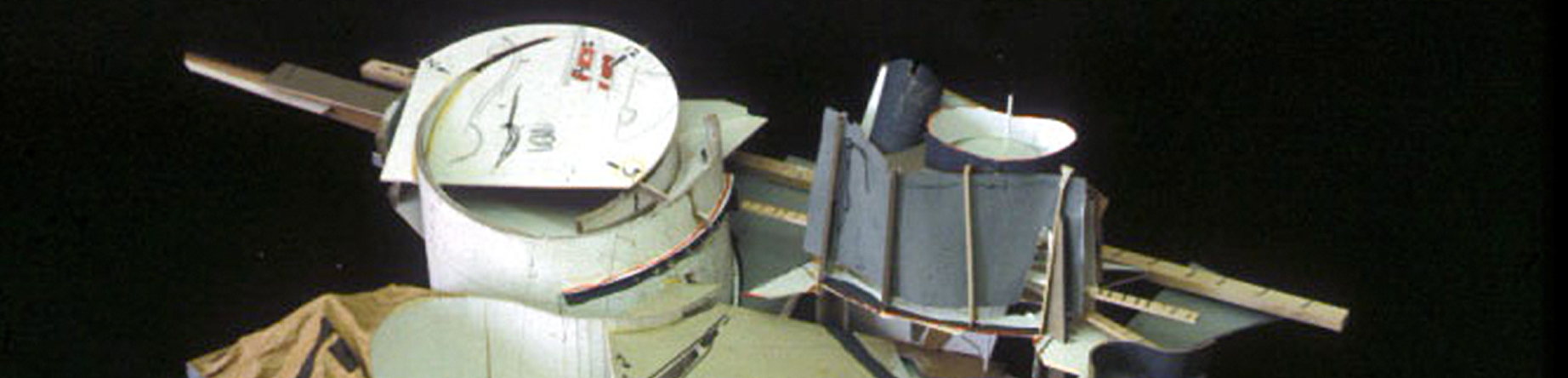

Image 1: reading of the urban site by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

Image 1: reading of the urban site by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

After my stint at the EPFL as a teaching assistant, I returned to the University of Kentucky—which became my academic home for the next 18 years—and looked to reiterate my European experience by blending an identical project brief with Swiss and American sensitivities. I asked to teach a vertical studio composed of second-year students with two third-year students whom I had taught the year before. The following comments are part of my recollections of one of the third-year student projects, chosen for the expression of voice as being undeniably present throughout the entire design process.

Two Teaching Methods

There have always been two methods by which I teach architecture. The first one is about imparting fundamentals and having students practice them through a rigorous process. Learning a step-by-step methodology is key to understanding how to generates new ideas. The process allows interpretation and the development of a personalized way of designing. The second method of teaching relies on improvisation, and the joy of finding one’s journey of discovery. I have always favored teaching both methods in tandem, which is difficult as these two processes seem for students at first incongruous and antithetical.

Ultimately, these two teaching methods should be seen as complementary. On the one hand, there is a rational and objective thought process that could dictate predictable results, while the other method is an expression of emotional and subjective reactions to particular scenarios. Let’s be clear, both are about rigor, but the risk taking of one versus the other offers vastly different degrees of freedom, all-the-while having student’s commit to a strong work ethic which will lead to innovative design proposals. With these thoughts in mind, my interest at this juncture of my teaching career at Kentucky was to combine the specificities of a rigorous design process with the indeterminations of an author’s subjectivity.

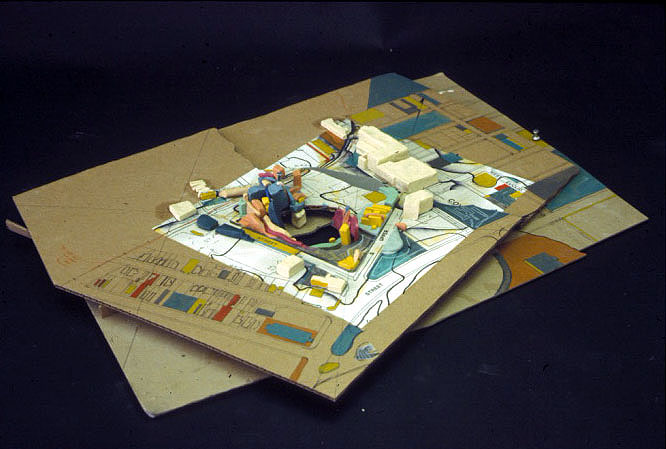

Image 2: Final interpretation of the urban site by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

Image 2: Final interpretation of the urban site by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

Whatever one’s intellectual stance in deciding which design process is appropriate, I argue that for students in the early years of skill acquisition, learning is first and foremost about finding their voice. It is not about solutions for the making of architecture—although that ambition is critical in proposing an architectural answer to a given brief, otherwise a student can rapidly create poster art legitimized by lofty ambitions. Finding one’s voice is more about computing the experiences and feelings about the act of designing.

Improvising is finding nuances, to discern moves and to ultimately discover patterns in one’s own process. It is a way of seeing, which altogether enables unexpected and astonishing moves to occur. Eventually, this approach leads to more formalized decision making, a mental process where ideas are distilled through an understanding of one’s own abilities as a designer.

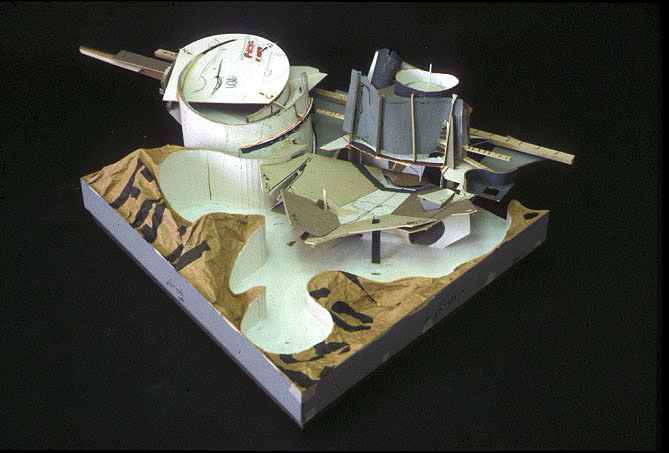

Image 3: Final interpretation of the urban site by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

Image 3: Final interpretation of the urban site by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

To improvise means to “make, invent, or arrange offhand,” and to be successful in this endeavor, there are principles which one needs to rely on. The first is that there is a need to educate oneself about basic concepts, the standards, the core fundamentals of an art form. Often students think that improvising is a gift that simply is about an expression of originality without building on shared characteristics and common elements.

Musicians such as Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, and my favorite jazz pianist Keith Jarret, work with a blueprint of their art to embellish or strip down standards and then use improvisation as a primary approach to creativity. In other words, improvising is about constantly reinventing oneself while playing out within the art form. It is finding, or when maturity sets in, expressing one’s inner voice, leading to a design personality and, in our case, an architectural language.

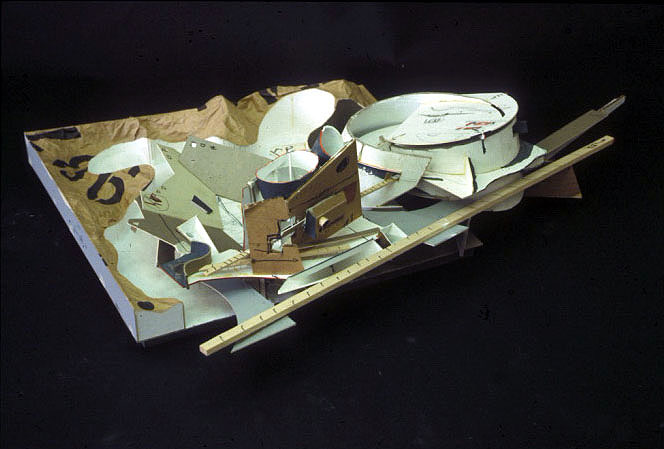

Image 4: Final interpretation of the urban site by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

Image 4: Final interpretation of the urban site by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

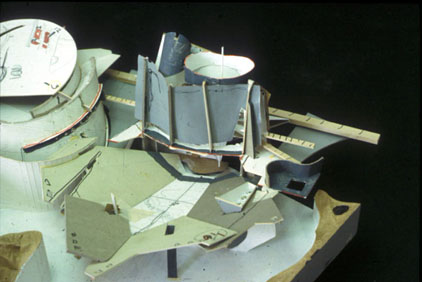

I regret that I do not have meticulously chronicled records of the process of this student project. I only could retrieve a limited number of images that trace the student’s direction as they bring out ideas about the landscape. The geography proposed structures that emerged from the site to punctuate and define the landscape in ways that had never existed prior to the intervention. At times, the moves were subtle, at other moments more forceful. All in all, the final model (Images 4-7) illustrate a remarkable sense of freedom, plasticity, and liberty in improvising the calling of the site.

Image 5: Final interpretation of the urban site by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

Image 5: Final interpretation of the urban site by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

Like a cubist painting, the three-dimensional model evokes notions of forms without resorting to representational shapes or tectonic interventions that have at this stage no functional attributes in the traditional sense where forms may suggest function and vice versa. There was, of course, an interest from my point of view to legitimize the initial brief: “Can a meaningful architecture be created without a program, without functions, and exist solely as a manifestation of a student’s inner voice?”

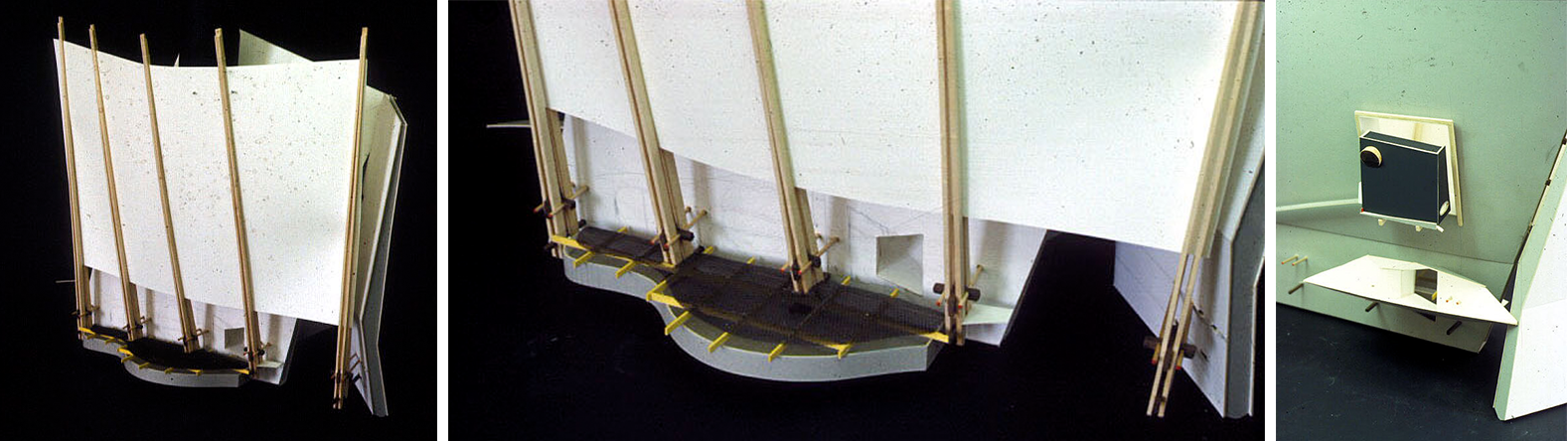

Image 6: Ideas of construction by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

Image 6: Ideas of construction by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

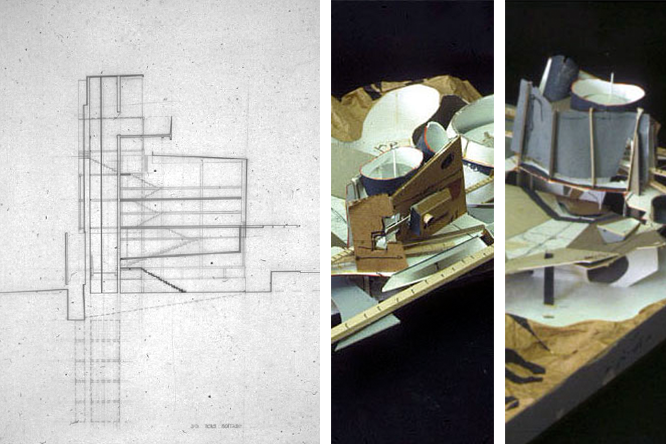

As the work progressed, architectural structures emerged, resulting in the need to cross examine them in plan and section, along with the first attempts to understand tectonics through methods of construction; ambitious prerogatives that were consistent with the scale of the model.

Image 7: Ideas of construction by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

Image 7: Ideas of construction by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

As an faculty member I came out of this process with the firm conviction that regardless of favoring one process over another, the importance was to understand that decisions should always lead to an architectural artifact; an academic object that was now part of the realm and discipline of architecture. Processes should never be the goal but rather a medium toward gaining confidence in one’s inner voice where you balance objective with subjective design methods.

Image 8: Section through a pavilion by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

Image 8: Section through a pavilion by Greg Skogland (author’s collection)

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy: Part 5

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy: Part 4

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy: Part 3

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy: Part 2

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy: Part 1

Architectural Education: The nature of IDEAS

[1] Robert Slutzky, Introduction to Cooper Union: A pedagogy of form, in Lotus International No. 27, 1980. p86.