Questions of Pedagogy, Part 5. My early years teaching architecture focused on imparting students with a design process; a methodology that would provide my second-year students with solid conceptual thinking. This approach was inspired by my own experience of Raimund Abraham’s teaching. Now that I was becoming an educator, many of my studio briefs espoused design strategies that existed outside of conventional notions of function (Question of Pedagogy. Part 2). In particular, I favored one where site conditions became a leitmotif to engage design thinking (Question of Pedagogy. Part 3).

Questions of Pedagogy, Part 5. My early years teaching architecture focused on imparting students with a design process; a methodology that would provide my second-year students with solid conceptual thinking. This approach was inspired by my own experience of Raimund Abraham’s teaching. Now that I was becoming an educator, many of my studio briefs espoused design strategies that existed outside of conventional notions of function (Question of Pedagogy. Part 2). In particular, I favored one where site conditions became a leitmotif to engage design thinking (Question of Pedagogy. Part 3).

As a registered architect, I had worked on professional projects that relied on a list of functions, from which I would interpret the client’s brief, set in place a program (a thesis, a big idea), and develop the project according to what I like to define as its calling. In my early academic responsibilities, I wanted to convey this architectural design strategy; of course, adapted to respond to specific years of study and the need for defined academic learning outcomes.

As a junior faculty, initiating students to architecture was a dauting endeavor—especially that the education of an architect is taught differently in the United States than in my home country Switzerland. Finding a balance between design and discipline specifics is one of the major differences, beyond the constant reminder that US programs in architecture favor a liberal arts education, often keeping students from being immersed directly with architectural themes in their freshmen year. To remain open to different teaching methodologies is key to academic freedom, and offers a chance to hone particular topics while allowing students to find their voice.

While I believe in finding one’s own voice, this typically comes after hard work understanding the fundamental underpinning of a discipline. How can you want to change something without knowing what you are building upon or going against? And yet, finding one’s voice is to have students investigate ideas despite the need for basic deliverables by which projects can be compared and contrasted for informed discussions among students and faculty.

The following project from my early years of teaching was an attempt to highlight the above concepts.

A second-year brief

In this second-year project, the studio brief was simple and was framed in a targeted way: Work with an abstract site in the shape of an elongated rectangle, and design a pavilion that negotiates the space between land and water. No assigned program, no functional requirements, simply a barren sloping landscape with the invitation for students to recognize the poetic implications of where water ends and land starts. The purpose of the theme was a way for students to generate a narrative, a story based on a principle of settlement.

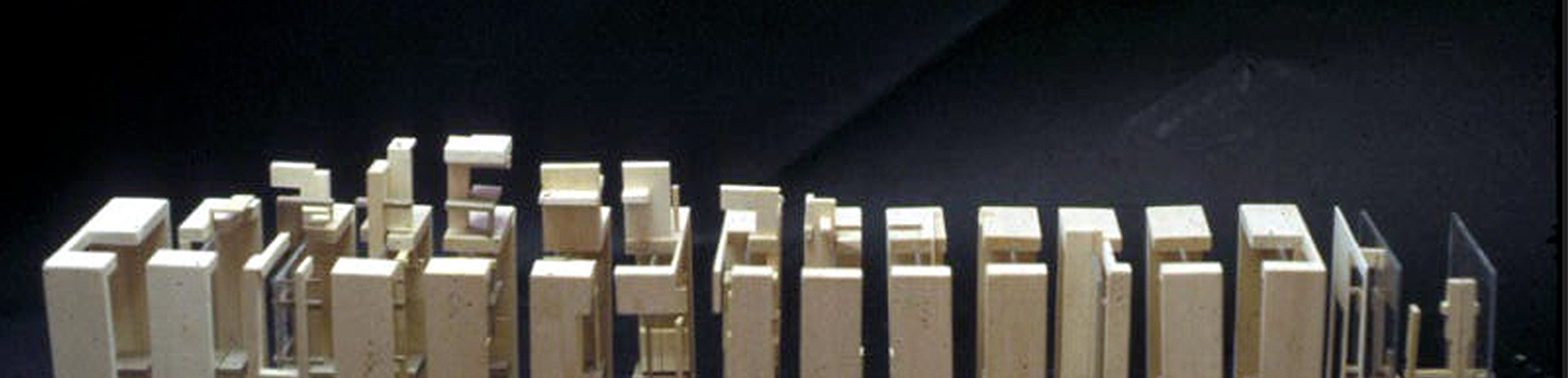

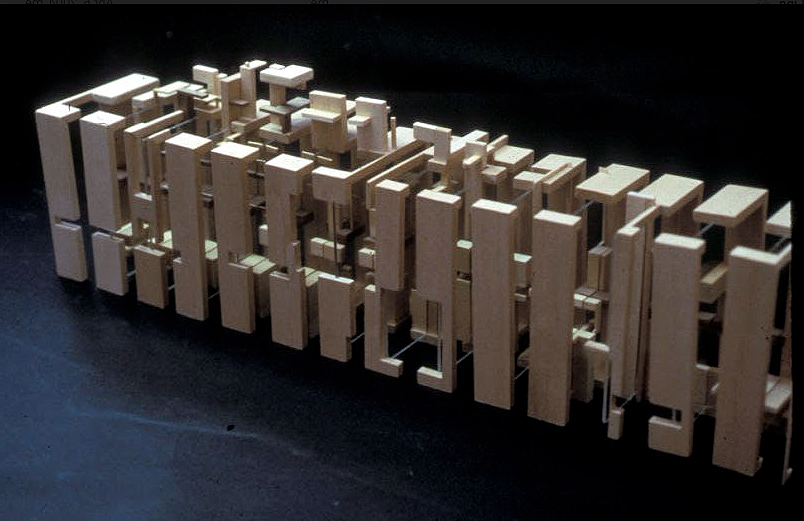

As expected, students struggled to identify this edge as its spatial limit, threshold, and passageway was intemporal due to the constant flux of the tide. Building on their limited vocabulary of structural elements such as planes, surfaces, columns, and beams, the initial proposals pinpointed poetic moments between land and water (Image 1, below). Image 1: first iteration of the project by establishing tectonics based on site conditions (author’s collection)

Image 1: first iteration of the project by establishing tectonics based on site conditions (author’s collection)

Site strategy

In the featured project (image 1 above and subsequent images), the first gesture of building on the site resulted in a lack of confidence in imagining the building emerging from the site, or the site becoming a building. Certainly, it was a seductive sketch model that emphasized the choice of a precise location while using a de Stijl vocabulary to enclose spaces.

First model

I still see many such models, and never know if the use of a single material thickness (i.e., chipboard) results in these overlapping planal structures, or simply that a spatial interest in seeking fluidity between space and rooms is the impetus to create such a three-dimensional intervention. What was refreshing in this proposal was that the student avoided responding to the brief with a predetermined form of ‘what a pavilion might look like (Image 1, above).

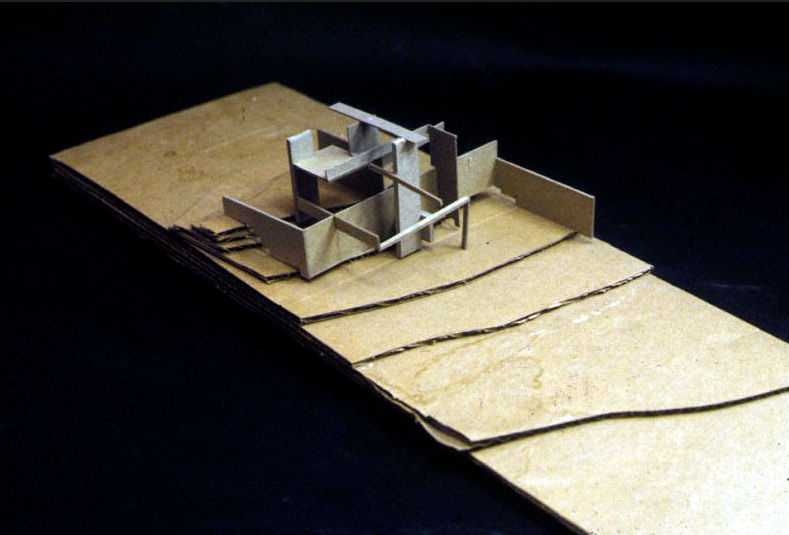

Image 2: second iteration of the project (author’s collection)

Image 2: second iteration of the project (author’s collection)

Second model

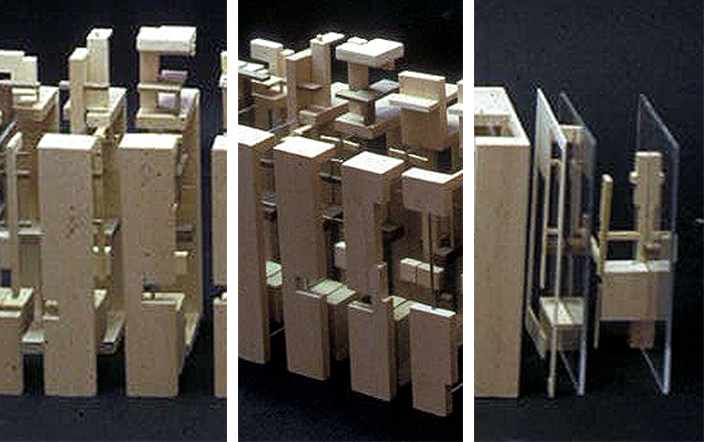

In a second iteration—the student opted to develop the project solely through sketch models—the first concept expanded into the water. A modular armature emerged, which eventually became the structural principal featured in the final sectional model (Images 4 and 5 below). By rotating the frame 90 degrees at the front of the pavilion (image 1 above), open air rooms negotiated a repetitive and ordered transition from land to water.

A pier structure began to interpret the brief through a vertical anchoring of the building to land (to the left of the model) while levitating walkways and a cantilever towards the water negotiated the infinity of the horizon (to the right of the model). Note the introduction of a second color in the choice of materials indicating movement and structural pylons (Image 2, above).

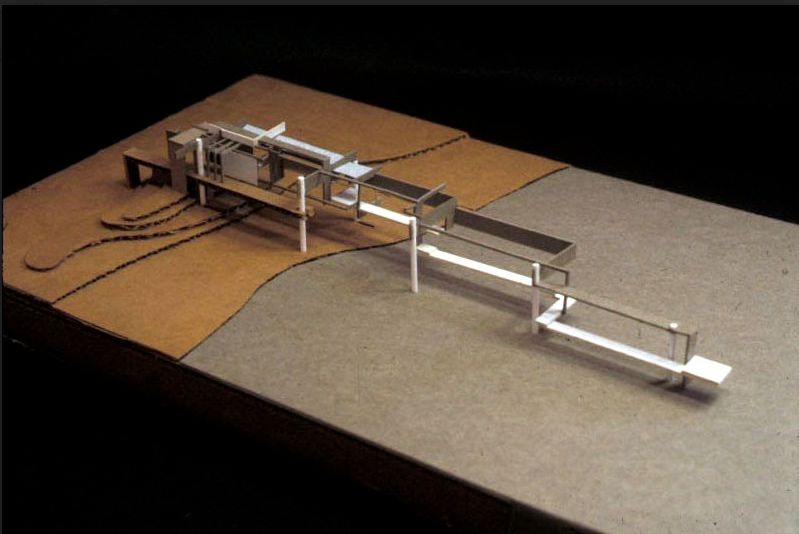

Image 3; third iteration of the project by establishing tectonics based on site conditions (author’s collection)

Image 3; third iteration of the project by establishing tectonics based on site conditions (author’s collection)

Third model

The last phase in the development of this series of models—remaining faithful in interpreting the project’s brief—clarified spatial enclosures while reinforcing outside rooms that could act as terraces suggesting diverse activities. The early pylons in the previous model became structural U-shaped frames suggesting two pavilions; one on land and the other over water.

Also, interesting to note (images 1-3) is that despite the abstract nature of the site, the student initially built the pavilion spanning the entire width of the site, then changed scale, and gave the landscape more formality by setting the intervention symmetrically on the axis along land and water, and ended up pushing the proposal favoring one side of the site as if the building was to define the edge of the site model. Finally, while densifying the elements of the building closer to the land, the student continued to measure the site by expanding the earlier cantilever into an elongated walkway hovering above the water (Image 3, above).

Image 4: final model of the project (author’s collection)

Image 4: final model of the project (author’s collection)

A conceputal change

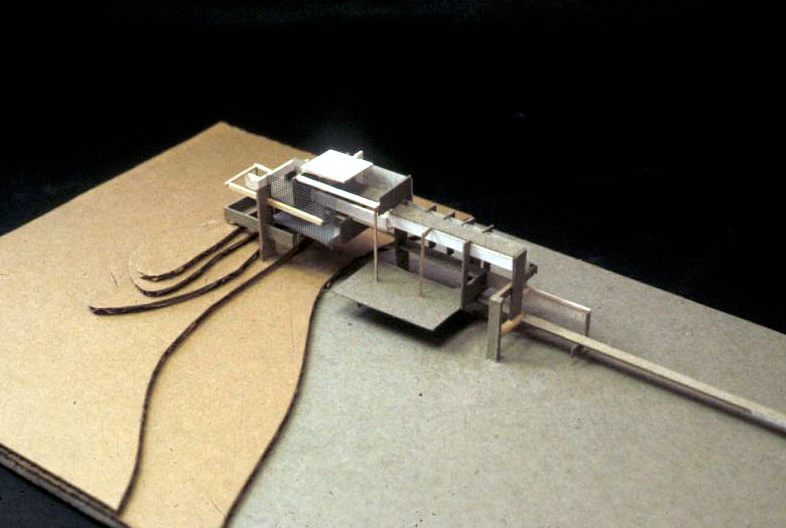

It is at this moment that an epiphany occurred. A moment of rupture. A time for reflection to see the project with another outlook. The first chapter of the project came to an end. The next phase thrusted the student off a direction that may have seemed a natural evolution of their process to, instead, discover the nature of the created object, the calling of the exhibited artifact (Images 4 above and 5 below). Here, after realizing the limitations of the brief, the student saw different potentials and pursued a line of investigation that set at center stage questions of section.

Abstracting key elements from the previous three models, sixteen vertical frames established an abstract order based on imaginary sectional cuts. Were they different moments within a project, or a subtle transformation from the first to the last section? These questions were among many posed and debated to advance the project, all with a clear understanding that the student’s intuition outplayed at this stage of the project any objective interpretation of the new formal artifact.

Image 5: final sectional model of the project (author’s collection)

Image 5: final sectional model of the project (author’s collection)

The student’s position did not exclude a careful reading of the tectonic moves from the peripheral definition of each of the sectional cuts to the spatial interiorities. The latter became the student’s primary focus and rekindled with the project’s brief to ask a seemingly simple question: When can one truly leave the origins of a brief? Perhaps, the most important lesson for the student was that the site remained a constant preoccupation during the entire process, but took several iterations moving from a building on a site (image 1 above), to a building BEING a site (image 5 below).

I invite the reader to scrutinize this model. One key element of my constant admiration and respect for the process—and this beyond the early dexterity of creating such a powerful proposal—is to see the gentleness of the site metaphorically be incorporate to finally extrude to the left of the model, morph into the interior of the section, and disappear slowly into the final Plexiglas frame; perhaps a gesture reminiscent of the early cantilever extending towards the water to negotiate the infinity of the horizon (Image 6 below).

Image 6: final sectional model of the project (author’s collection)

Image 6: final sectional model of the project (author’s collection)

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy: Part 6

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy: Part 4

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy: Part 3

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy: Part 2

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy: Part 1

Architectural Education: The nature of IDEAS