Unbuilt projects and competitions. Years ago, when I had the occasion to teach in Venice, Italy, I became aware of the famous 18th century vedute (view paintings) and capricci (imaginary view paintings); specifically those of Italian painters Guardi and Canaletto.

Perhaps one of the most famous of these paintings, one which still makes me marvel, is located at the Galleria Nazionale in Parma. Often referred to as Capriccio with Palladian buildings it was painted in the 18th century by Giovanni Antonio Canal, commonly known as Canaletto (1697-1768).

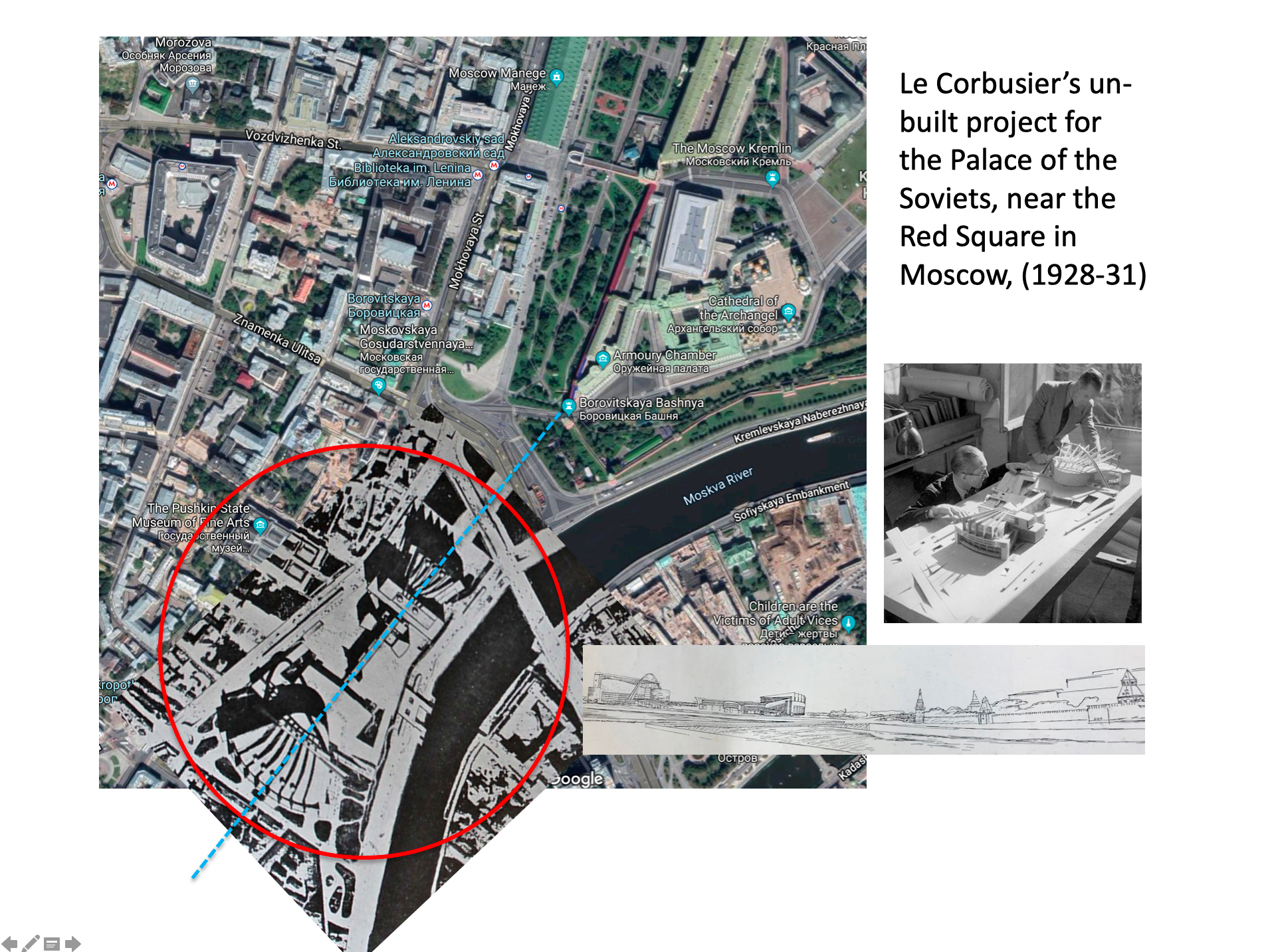

This pictorial style is called capriccio—“an architecture fantasy, placing together buildings, archaeological ruins and other architectural elements in fictional and often fantastical combinations.” At first glance, one assumes that this is a view of Venice at one of its iconic junctions on the Grand Canal; namely the Rialto bridge with the adjacent market to the right. However, the wonderful painting is imaginary, as the centrally depicted bridge is the legacy of an unbuilt competition entry by Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio (1570); one of many projects submitted for the reconstruction of the old wooden Rialto bridge (Image 1 below).

Image 1: Google- Giovanni Antonio Canal, commonly known as Canaletto (1697-1768) titled Capriccio with Palladian buildings (1740)

Image 1: Google- Giovanni Antonio Canal, commonly known as Canaletto (1697-1768) titled Capriccio with Palladian buildings (1740)

As one looks closer, the flanking buildings on either side of the Rialto are designed by the same architect, but this time they were completed in the nearby city of Vicenza. The ensemble of the bridge, the Basilica Palladiana (right) and the Palazzo Chiericati, (left) comprise a view of Venice that became a leitmotif of Canaletto when painting for wealthy English patrons. It was customary for young British aristocrats returning from a Grand Tour in Europe to purchase memorabilia, sometimes a painting or little metal miniature buildings. Here, the artist’s artifact suggests Venice, but a Venice that only exists for the pleasure of the patron’s imagined memory.

Aldo Rossi

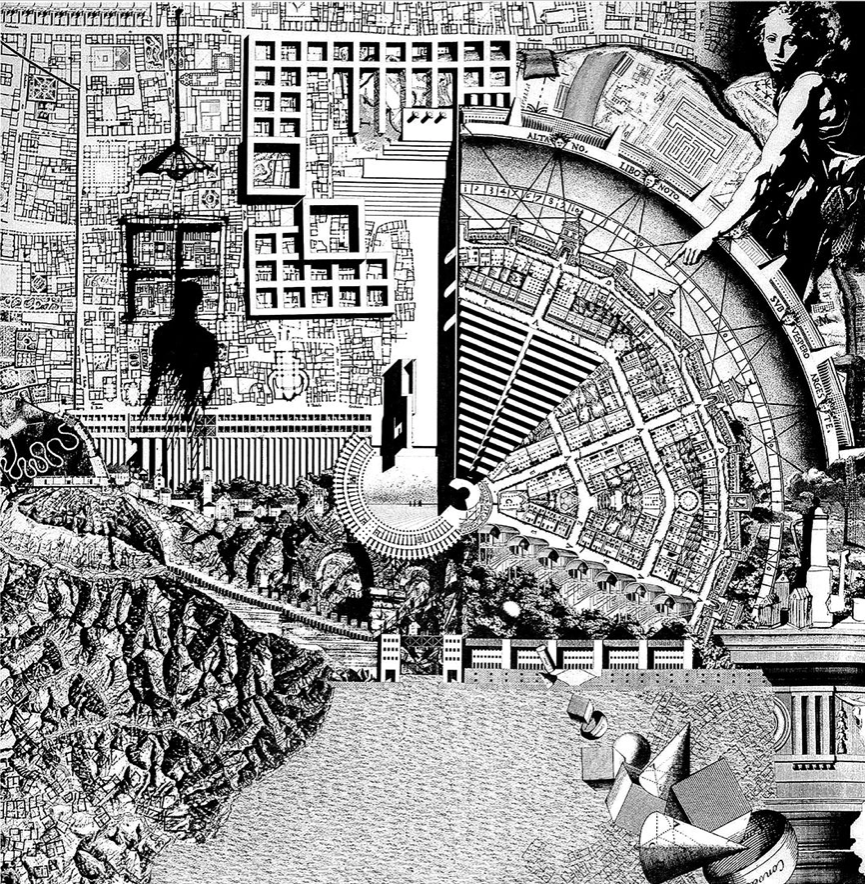

Image 3: Aldo Rossi, The Analogous City, 1976, with Eraldo Consolascio Bruno Reichlin and Fabio Reinhart.

Image 3: Aldo Rossi, The Analogous City, 1976, with Eraldo Consolascio Bruno Reichlin and Fabio Reinhart.

The discovery of the idea of capricci reminded me of Aldo Rossi’s iconography of the analogical city (Image 2, above), a city built of past and present artifacts enhanced by the author’s autobiography formed by his ideals and memories (of course Rossi mentions Canaletto’s painting as key for The Analogous City). I asked myself, if this is a method of understanding and building a city, what would happen if I could catalogue and research cities and map select unbuilt projects and competitions in the hope of creating my own analogous city; a city with an imaginary skyline that would posthumously accommodate rejected and aborted projects created for those great metropolises.

The mapping of those cities would integrate, disrupt, and challenge the existing morphology and create a real-utopic city (philosophical term used by Ernst Bloch), a city similar to those found in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities where he suggests cities in formation or cities as the junction prior to falling into ruin, leaving traces of a city that could have existed.

Two initial research questions

History and fiction bleed into each other, perhaps a legacy of my early childhood memories of Vienna and my later understanding of how cities are always layered and caught between imagination and reality. This became a major underpinning in the work that I would embark upon. Two further thoughts complement my initial impetuous idea as a foundation of my new research.

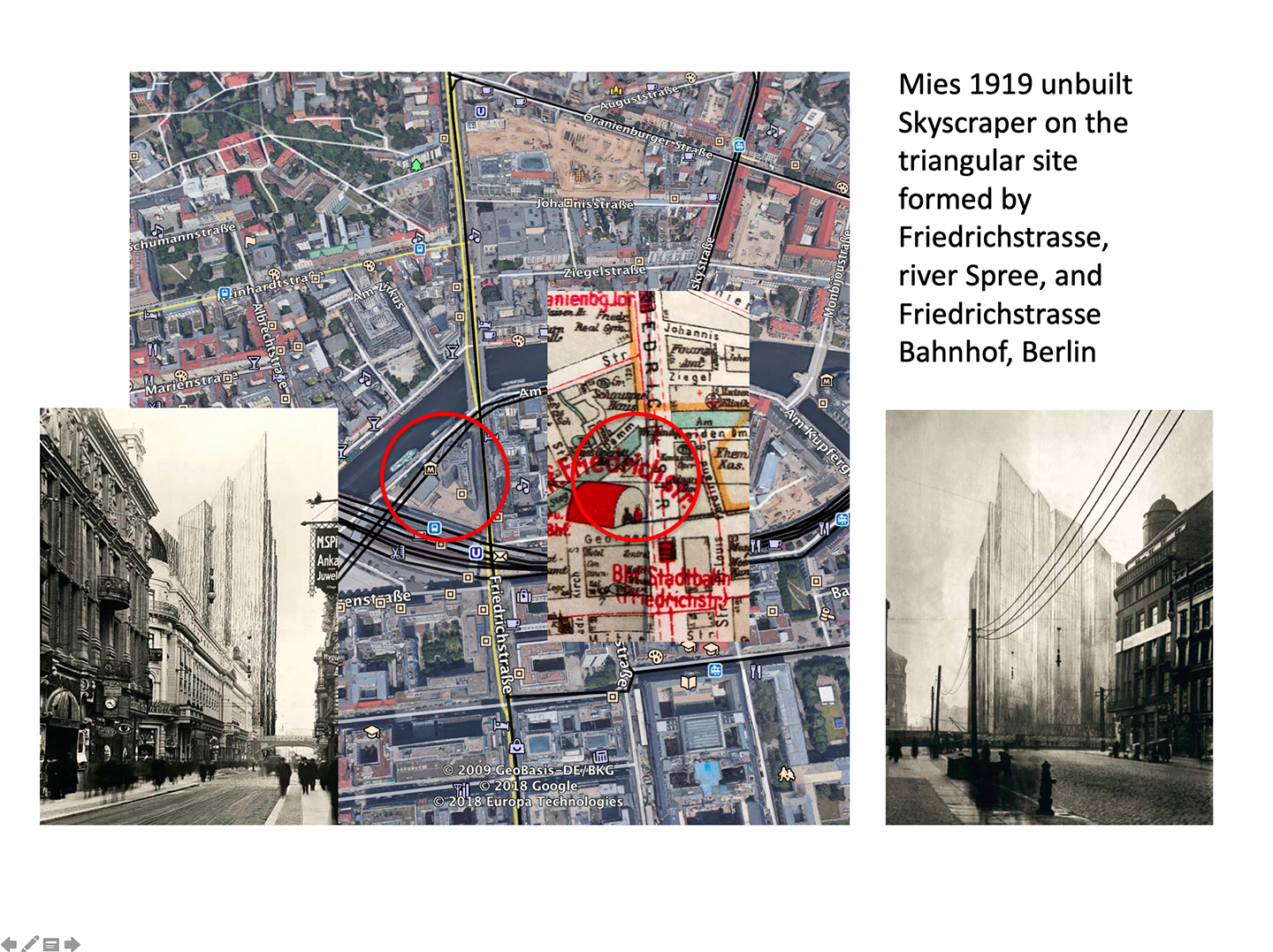

First, what would happen if the question of creating this analogical city was extended to understand where other unbuilt projects are located. For instance, I had always known about Mies van der Rohe’s seminal Friedrichstrasse glass skyscraper in Berlin, but was unsure of its exact location. Lo and behold, when I finally pinpointed its position at the Friedrichstrasse subway station, I could only reminisce on passing there each time I had crossed into East Berlin through the Tränenapalast (palace of tears), the nickname given by West Berliners to the station (first image below under three research examples).

Second, over the years I became fascinated with understanding why so many unbuilt projects and competitions continue to hold key roles in the history and theory of architecture. My curiosity started when I became aware of a number of competition entries for the 1985 Venice Biennale that included the unbuilt project of Le Corbusier for the Venice hospital. I asked myself why would contemporary architects deliberately collage Le Corbusier’s unbuilt project alongside their own vision for the Cannaregio neighborhood of Venice? (Peter Eisenman, Bernard Hoesli, and Rafael Moneo)

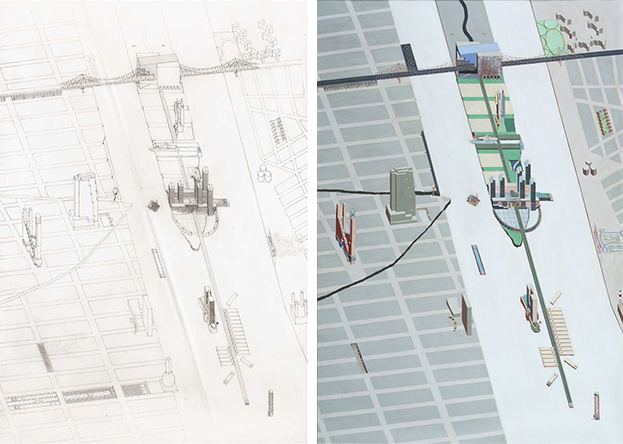

Image 4: Google Rem Koolhaas, Welfare Island

Image 4: Google Rem Koolhaas, Welfare Island

This link reflects my first peregrinations into building a Rome, a Venice, or a New York that could have existed; where buildings coexist through time and formally cross pollinate similar to Canaletto’s capriccios, Rossi’s analogical city and, to add another example, Rem Koolhaas’s Welfare island project (Image 4 above), another proposal for an analogical city depicted by Zoe Zenghelis in Delirious New York.

New entries will continue to populate this web page with both well known and lesser known unbuilt projects. If a reader would like to share a particular favorite unbuilt project, please email me or simply post your suggestions in the blog comments.

Three research examples

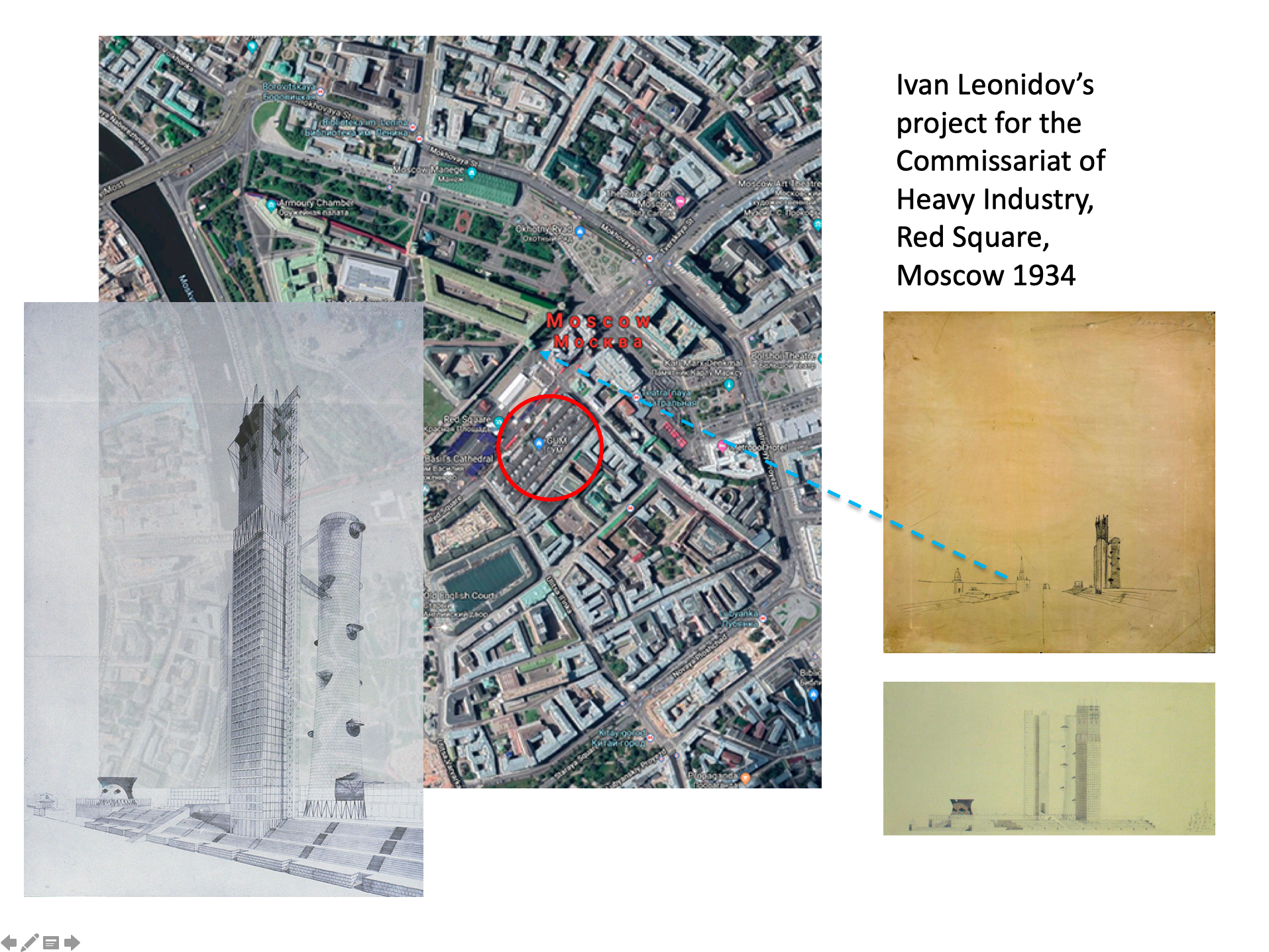

Note: Interesting that the two featured projects in Moscow (by Le Corbusier and Ivan Leonidov) are in such close proximity to each other but three years apart in proposals.