A compass set. For an architecture student in the early 1980s, owning a compass was not a luxury, it was a necessity. This, along with other required mechanical tools (drafting instruments) including a triangular metric scale (which in Europe serves both architects and engineers), various triangles, ruler, T-square (parallel bars were rare and expensive and were seen as an American luxury for a European student), protractor (measured angles), templates known as French curves (to draw complex geometry), eraser shield, and the ubiquitous item that was expensive but lifesaving – Rotring’s famous rapidograph ink pens.

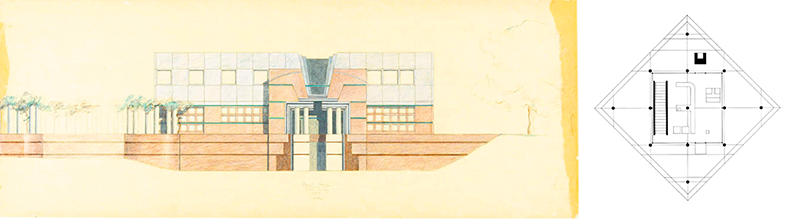

Beyond these technical instruments, I cannot omit from my list the pencils, sketchbooks, and the invaluable paper that I came to know in America under the name flimsy (a transparent paper for tracing which came in different weights and had a recognizable yellow color called canary or buff) (Image 1, above).

While interning in an architecture office in New York, I learned that yellow tracing paper was used for sketching, while white tracing paper and velum were for final drawings and renderings. This is because when printing, drawings on white trace seemed to have more luminosity.

Many of the instruments I listed above, as well as sketch paper, have slowly disappeared with the advent of digital drawing and design programs. At the institution where I teach, we value crafting drawings, although we understand and forcefully promote digital renderings as integral to a student’s design thinking.

Sketching

During my studies, sketching was considered an art form and was not easy to master. Practicing sketching with a controlled freedom was a goal for any student. On the other hand, producing sketch-drafted drawings, followed by precisely drafted ones in pencil, ending eventually as inked drawing for final reviews, was integral to the design process (Image 2, above).

Many of my drawings that I remember as successful were based on how I could geometrically and mathematically draft my ideas. While recognizing changes to education and practice over the past decades, I continue to stress these drawing techniques with my current students; in particular as the digital has opened immense creative design possibilities that I could never have envisioned during my studies. I firmly believe that to be more than proficient in a digital age, it is still necessary to master a variety of drawing skills.

For students, the use of computers and their powerful drawing tools have become second nature. This doesn’t begin to count the increased presence of Artificial Intelligence (AI), with its ambitious promises to creatively support us – to the extent that one day, we will realize that AI has rendered the architecture profession quasi obsolete.

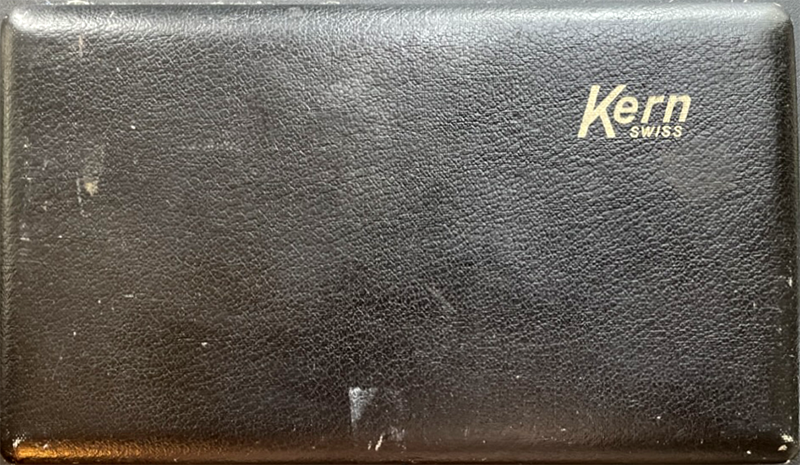

Kern Compass set

As a student, I owned a compass that was precise and inexpensive. It initially served to draft garrulous geometries, that—retrospectively—I believed would set me apart, as they seemed creative and unique. I came to realize that what was important in any project was that geometries become form (geometry with meaning) in order to translate my ideas into an architectural space.

Today, I see similar moves with my second-year students, to the exception that for them form making, along with a quasi-obsessive fixation on the object, makes the apprenticeship of space making such a challenging task. For most of them, coming out of first year, architecture is about making “cool geometries” and they find it difficult to reconcile form, function, poetry, and programmatic ambitions.

My first REAL compass set

One day, and because of some very sad circumstances in my life, I inherited a compass set (aka., engineering drafting tools). I was honored to have been gifted such elegant instruments, and upon looking at them, realized that it was not a generic set. It was a Kern compass set whose name was synonymous with the Swiss-made label of excellence that conveyed precision and technical perfection, along with a restrained aesthetic beauty.

While other Swiss brands such as Jakob Amsler and Gottlieb Coradi, or German makers Haff, and Keuffel & Esser, manufactured high quality precision compasses, Kern, in the early 1900s became the Rolls-Royce of high precision drawing instruments. Needless to say, I was in heaven, and eager to use the tools during my architecture studies.

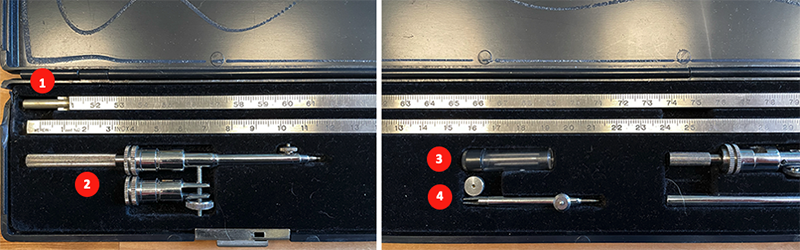

The set (Image 4, above) has a black leather case with an outside inscription that reads Kern Swiss. As you open the cover, there are ten pieces that serve a variety of purposes, each carefully assigned to their proper place through recessed slots in a blue velvet lining (Image 5, below).

The description of the compass instruments

To describe the set’s content, let us start with the three main compasses (note that the red bold numbers correspond to those in the following images). The first compass has an adjustable down joint holding the lead (1), that can accommodate other pieces (pen and ink points or extension arm). In the set, above that compass, one finds an extension arm to draw circles of a larger diameter (2). The second compass is a proportional dividing compass with two sharp needle points to record dimensions and report those measurements to scale, to compare, or to transfer a measured distance to another point in the drawing (3) (Image 5, below).

The third instrument is a bow-spring compass (4). Contrary to the previous two compasses that are constructed with a hinge mechanism and a screw, the bow-spring compass is based on a spring where both legs expand simultaneously outwards through the movement of a serrated center wheel. This allows one to change the radius of the circle all the while maintaining an impeccable accuracy. All three compasses have a ridged cylindrical handle for easy grip of the instrument.

The particularity of the bow-spring compass was its ability to finely calibrate when drawing very tight circles, resulting in incredibly precise drawings. Each of the three compasses are ergonomically designed to feel good in one’s hand and brought my drawings to a new level of excellence. I continue to share with my students the importance of owning excellent instruments as they will help them in accurately representing their ideas.

Included in the Kern set are two ruling pens (5) (Image 6, above). Of similar shape but presented in two sizes, the pens are used to draw precise and consistent lines of a variety of thicknesses while inking a drawing. As with any drawing instrument, users need to be precise in the handling. Not only is it important to hold the pen at a 90-degree angle to the drawing, but to load them with ink requires dexterity. This task is done by inserting ink between two flexible metal arms and tightening them carefully by turning the wheel which will bring the arms towards each other to create a desired line thickness (aka line weight).

One quickly learns that this maneuver IS the easy part. The tricky parts are uploading the ink rapidly without making a mess ON the drawing, and promptly picking up the previously drawn line (with an understanding that the previous ink had already dried) so that there is perfect continuity between line thicknesses; and this, without any smudges. God forbid you didn’t clean your pens, as maintenance of a ruling pen was a nightmare as ink would dry fast and cleaning after each use was essential. If you ever forgot to empty the ruling pen, one had to provide love and patience to remove the dried ink!

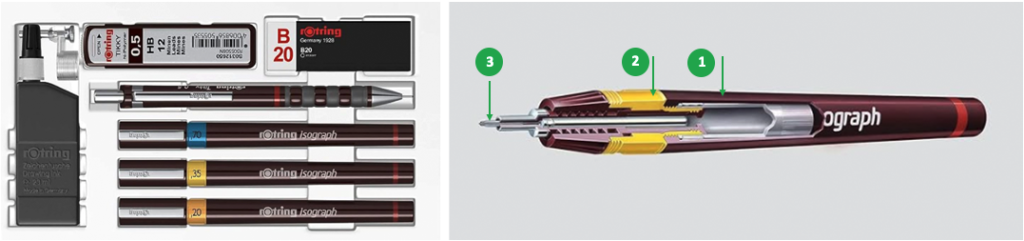

This is why for most of us it was critical to rapidly invest in a set of Rotring Isograph Technical Drawing pens as they made drafting in ink easier than a ruling pen. However, they were expensive, very expensive for most students, but like owning a computer these days, the pens became indispensable. While ink pens saved time, they were even more picky than ruling pens, and demanded constant attention (Image 7, above).

If at the end of an inking session one forgot to screw back the cover, troubled started—the ink pen was dead! If you were courageous, which I was, I would unscrew the pen holder (1) (Image 7, above right), then remove the color-coded barrel holding the nib (in this example, the universal .35-line width) (2), then slowly pull out the stainless-steel nib (3) and clean it delicately with warm water. To set the nib back into the slot without bending it (especially if it was a .13 mm size), one could consider oneself a hero.

In conclusion, inking the traditional way or with Rotring pens demanded dexterity, concentration, dedication, and a trained eye to not mess up the drawing in terms of line weight. And let’s hope to never experience the obvious beginner mistake of letting ink flow under the drafting ruler or triangle, especially if it didn’t have an inking edge. How many coins were taped to the underside to create an inking edge!

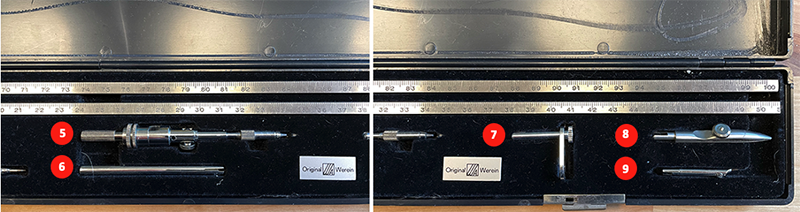

In addition to the instruments described above, the Kern compass set included a drawing nib and an inking attachment nib (6) (Image 5, above), as well as a screwdriver (7) to tighten any loose parts of the compass (Image 8, above).

When drawing with a compass, much of the precision relies on the ability to finely calibrate the hinge. If the compass is not sufficiently tightened it may loosen slightly while rotating, and the leg holding the lead could widen thus creating a less than perfect final circle. The screwdriver is elegantly designed (like any Swiss instrument) with a ribbed exterior making it easy to grip firmly. Ingeniously, inside its hollow cylinder are additional pins and lead.

To add to the precision of each compass, Kern instruments are made from plated metal to provide the necessary durability. I remember that after each use, I carefully cleaned the instruments and set them back in their resting position as if they never had been used!

An Italian beam compass set

My second set was purchased during a teaching stint in Venice. Visiting my favorite art and design store near Campo Santa Margherita, I saw for the first time a beam-compass that was fabricated by Original Werein numbered 940M. Beyond being a tool of incredible precision, its claim to fame was that one could draw a one-meter circle—a little over three feet in US measurements (Image 9, above).

Set elegantly in an elongated box, there were two fifty-centimeter square metal rods that, once connected through a male and female socket, allowed one to draw circles larger than any regular compass—even with several extension legs (Image 9 above, and image 5 – red dot No. 2, above).

To use this instrument, one needed to insert at one end of the rod (1) a needle (pricker) point anchored in a holder with rough and fine adjustments (2), as well as a pencil point (5) positioned to draw the desired circle. The two rods show a total of 100 centimeters in increments of one millimeter. I have recently seen a similar one with the difference that three rods were needed to form one meter. Needless to say, when using it, the compass becomes a piece of conversation.

Additional items in the set included a plastic lead holder (3), an additional beam to measure distances (4), Rotring pen holder (7), ruling nib for inking (8), and extra arm holder with pin (9). This set has been a great companion for projects demanding the precise drawing of larger radiuses. Unfortunately, the protective felt is missing on the cover! (Image 10, above)

A German compass set

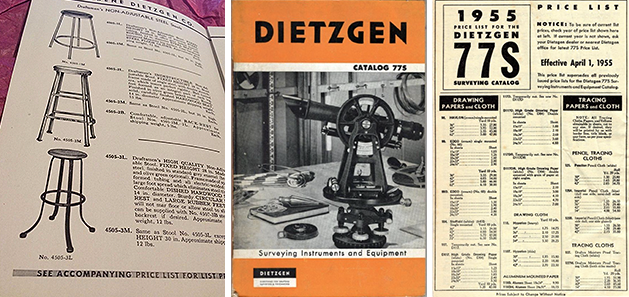

Years later, I was gifted a master pro Dietzgen drafting set No. 1212PJ by my father-in-law. It belonged to him as a young adult and was purchased in order to complete (and excel I’m sure) in a correspondence drafting class. Just looking at the number of pieces the set contained, it must have been a luxury in the mid 1950s (Image 11, above).

Although the name on the set reads Dietzgen (a German name), the “Dietzgen engineering supply company was founded in 1885 in Chicago by the German immigrant Eugene Dietzgen. The first manufacturing facility opened in 1893, producing T-squares, drawing boards, surveying instruments, drafting instruments, [slicing rulers]and other engineering supplies. High quality and craftsmanship of the tools made Dietzgen sets highly sought after.” (accessed 12.12.2023: https://ihsi.omeka.net/items/show/6). In what was to become an empire, specific catalogues were created to sell the products that included, to my delight, drafting stools, chairs and tables, and drawing leads aimed at serving draftsmen with their Dietzgen precision sets (Image 12, above).

Research on this set suggests that its fabrication dates somewhere between 1930 and 1950. In fact, I found the next generation set numbered 1213 PJ dated c. 1930, thus, I am happy that it is still in such perfect condition. If it wasn’t, I understand that Dietzgen drafting sets (who in 1908 purchased their drafting instrument factory in Germany) had a lifetime guarantee. Lucky me!

My last compass set

When I was living on the west coast, I discovered an even larger Kern compass set in a San Francisco store in Chinatown. While I had moved to the digital world and no longer needed to draft by hand (although I continuously sketch, conceptualize, and diagram with my favorite 5.6 mm graphite pencil), the set was so tempting with its elegance and immaculate condition. Of course, I had to own it and, while I have rarely used it, this compass is amazing given the versatility of all of the instruments and remains next to my desk as an object of beauty.

Conclusion

The brief history of my modest collection of compass sets is not only about the beauty of these precision instruments, but mostly to draw attention to the idea that to create works of great precision the will of the artist has to partner with the best instruments in order to translate ideas. Today, especially for architecture students, digital drawing software programs are taken for granted.

The ease of creating by simply punching appropriate buttons doesn’t compare to the experience, at least once, of crafting a beautiful drawing by hand. There is an elegance and precision to the mastering of line weight, the pleasure of drafting, and above all, a pride in seeing the aesthetic results of labor.

This is not to say that a digital drawing does not carry a sense of delight in the art of making. But hands down, and without being old fashioned, the art of making by hand is still something that remains exceptional when well done with some sense of indulgence, decadence, and sensuality.

Additional blogs of interest

Harrods mid-century cocktail cabinet

Secrétaire a abattant

Post Office Box cabinet

Cooling board table

Tri-fold mirror

Thanks for sharing, a really nice collection.

Werein was an Italian frim. I thought they made their own compasses so your beam compass might be Italian instead of german?

Dear Mike, Thanks for the comment. I conducted research but could not find a country for the maker of the Original Werein. Given its German name, I assumed it to be German. However, I purchased it in Venice, Italy, thus you might be right. I will make the changes to reflect your comment. Amities, Henri

Thank you for sharing your research.

I am in search of origin of a Compass box that I purchased decades ago. I shall email you the details in case you can help.

Dear Sir,

By all means, please share with me what you are looking for. Happy to help. Amities, Henri

I have been a collector of vintage items since a young age. Sometime in 1995, I acquired this set from a Delhi antique store, modestly labeled as “drawing tool box” and was reasonably priced. I brought it home and it had been stored away for over 25 years. It was during the pandemic I decided to catalogue my collection and this box got my attention. The box had multiple markings “Le Corbusier, Chandigarh” on it. Having never heard this name in my lifetime, I decided to research it. This is when I found out about Mr. Le Corbusier, who was the most influential urban planner and architect of the 20th century.

The various markings clearly indicate that this box had some historical significance with Le Corbusier, Chandigarh.

One of a kind Vintage Drawing Instrument Set, Drafting Compass Compendium, Circa 1930 used by Mr. Le Corbusier while living and working on building Chandigarh.

This is a standard full-set of Technical drawing instruments, Drafting Compass. Interior finished with rich maroon velour lined tray with silk covered hinged box lid.

Top of the box is a plastic lable marked “Baasler regd trade mark” on the Bottom left corner corner lable marked Kilburn. The box has 2 extendable shelfs in the top shelf holds 13 steel tools(8 tools 5 attachments) the Bottom shelf holds 13 steel tools. There are 7 french curve ruler (Burmester curve set) below the bottom shelf at the base of the box (image 7). The rulers of Size Curve NO. 1,2,3,4,5,12,10. Interestingly, one of the tool is labeled ‘Baasler’. The box has various marking indicating the name Le Corbusier, Chandigarh. There is a writing on the top edge upper lip of the box penned in ink also on the underside of the box it is clearly carved “Le Corbusier Chandigarh”. On the silk hinged lid is a hand written reference number Inside and at the base of the box on the paper lining it’s marked in ink “Le Corbusier Chandigarh”. Inside the box is a small paper note in ink marked “Le Corbusier , Chandigarh and ARI No. 102” referencing the file record of this Draftingcompass.

Sorry for my late reply. Holiday travel… Wow, you are a lucky person and should cherish this unique artifact. It seems a true historical items. If you can, please kindly send me some pictures of the set. I am utterly curious to see it now, especially being an architect, and loving your country.

Dear sir,

I have just sent across few images to your yahoo email account. I have also shared my cellphone numbers incase you need additional information or images. I am available on WhatsApp too.

Warm regards

Gopal