Segovia, Spain. I remember arriving on a sunny mid-November morning at the outskirts of the town of Segovia, Spain, and seeing for the first time the magnificent Roman aqueduct there. The warm winter light bathed the imposing arches, accentuating the majestic masculine stone features (Image 1 below). The structure serves as a symbolic gateway to the old medieval city to the north, and the gridded Roman encampment to the south, with the Cardo and Decumanus arteries that define any Roman military settlement.

It is at this precise point (under the aqueduct) that one enters the city, a moment where the unmortared structure of granite stones showcases the double arches at their fullest height of 100 feet. To the east and west, the aqueduct joins the horizon and slowly fades away into the countryside, until finally reaching its water source, the Frio River 10 miles to the south-east. It is interesting to note that water was transported by the aqueduct from this river to the city until 1950, surely nearly two thousand years of use!

Years ago, I visited another of this famous building type: the Pont du Gard located in southern France. The aqueduct there is majestic, situated within the idyllic landscape that bridges the Gardon River outside the Roman city of Nîmes (Nemausus in Latin). Despite the splendor and architectural ingenuity of the Pont du Gard, the aqueduct in Segovia, Spain, seemed even more prominent because its slender arches acted as both a foreground and background to the medieval city; similar to how the scale of Roebling’s Brooklyn Bridge must have appeared against the skyline of lower Manhattan when it opened to the public in 1883 (Image 2, below). I should note that the aqueduct in Segovia was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985.

Aqueducts

Aqueducts were integral to Rome’s vision of setting in place key urban infrastructures to serve citizens in the numerous provinces; territories extending from England to Africa, and as far as Babylonia (modern Iraq)—all surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. Structures such as basilicas, triumphal arches, amphitheaters, colosseums, and residential housing blocks constituted important parts of any Roman city. Equally important were the monumental aqueducts that expressed the genius of their civil engineers.

Not only were these edifices built with know-how, they were vital means to transport clean filtered water to urban areas. Aqueducts needed to negotiate complex topographies to channel water artificially from distant sources to, in this case, the city of Segovia. Thus, the construction superimposed multiple arches to gain the necessary height needed to traverse peaks and valleys while keeping the water flowing towards its final destination—generally at a one percent slope.

Segovia’s symbol

I found along my walk through the city, countless reminders of the acqueduct’s importance to its citizens and cultural identity; and this, often in inconspicuous places such as house facades, or on water and electrical panels mostly set into pedestrian walkways (Images 2 and 3 below). UNESCO’s site mentions that Segovia’s aqueduct “is the symbol of the city and can in no way be separated from Segovia as a whole.”

Entrances

While visiting Segovia, I had several free hours and, after marveling at the aqueduct, I ventured to discover the city with some freshly deep-fried churros drizzled with chocolate in hand. Like most European historic centers, the city’s urban fabric is made out of buildings that express styles developed over centuries. Cities are never homogenous and tell stories like a complex palimpsest.

As an architecture student, I was trained with a French sensitivity, one which is polytechnic and that espouses to classify, systematize, and organize ideas in a similar way to those developed by architect Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand in his 1830 Recueil et parallèle des edifices de tout genre. Thus, when I walk around any city, I notice patterns and types that hold my attention, recording them photographically (unfortunately not as often as I would like in my sketchbook).

What initially drew my attention upon entering the medieval city of Segovia were the discreet and majestic front entrances that are part of the repertoire of my list of curiosities. Doorways are not simply doors to an inside domestic world. They are passageways, limits, and edges that reflect the status of the inhabitants with designs meant to impress passersby, and engage those invited to cross the house’s threshold.

Entrances showcase architectural attributes such as styles, decorations, and ornamentations, structural principles (post and lintel or arch construction), and the usage of noble materials that typically have a scale that is foreboding to mark the secure nature of the portal (Image 5, below).

Detailing

As I contemplate the lexicon of opening types, I am reminded of the symbolism, construction, and craftsmanship used in detailing these entranceways. Designed in an integrative manner to accommodate pedestrians and carriage movement passing from one world to another—the pedestrian public to the private realm—artisans accompanied these transitions with artifices of various scales. Along my walk, I found Medieval, Islamic, Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Neo-Classical, 19th century, modern, and even a few contemporary interventions that collectively form a wonderful street unity—all of them serving as rich legacies showcasing the city’s centuries of slow change.

Doorways are typically accompanied by intricate detailing which varies in visual scale (Images 7 above, and 8 below). As an overall composition, the architecture extended to the scale of the city (Image 5 and 6 above), the scale of the human (image 7 above), and the scale of the hand (Image 8 below). Through this attention to construction and detailing, artisans demonstrated their mastery of various skills by creating memorable moments of intense visual delight.

Often, at the entrances to patrician houses (Segovia was an important center of trade and cloth industry in wool and flannel textiles), one finds a family crest or an iconic symbol of a family trade firmly anchored above the entrance on the key stone or symmetrically in the overall doorway composition.

Street facades

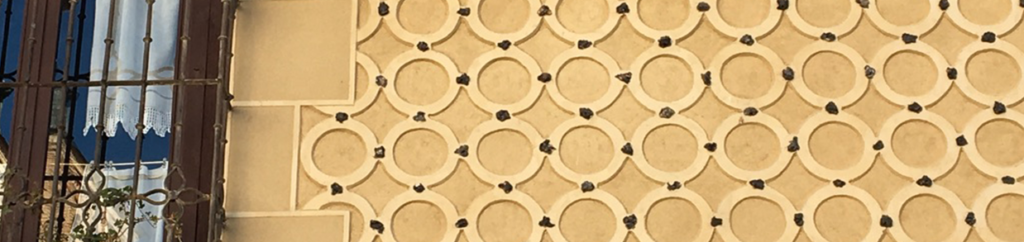

There is so much to admire when looking at each façade, but the narrow and winding streets of Segovia offer something even more beautiful and astonishing. Wall after wall, surface after surface, features decorative elements that create the uniqueness of each house and streetscape. While each facade varies in size, composition, and geometry, the mosaic of these architectural facades is often referred to as Moorish Patterned Wall Decoration, a legacy of the Islamic conquest of Al-Andalus, the name used by the Muslin population for the Iberian Peninsula during its conquest between 711 and 1492.

The arabesque motifs are pure splendor and give such personality to each building while showcasing the societal hierarchies of its inhabitants. There are hundreds of intricate geometries—suggesting the Arab world’s deep knowledge of mathematics that translated into the arabesque patterns—and while most of them have been repaired or even totally redone, I could not find during my visit the surface of any façade tessellations mimicking its neighbor (Image 11, below).

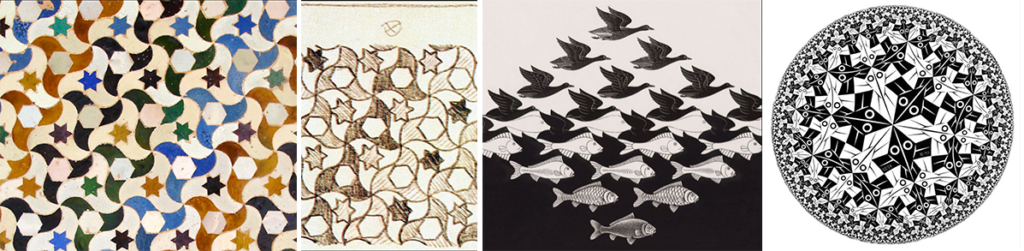

The planer repeated textures vary from simple to geometrically intricate linear motifs, to interlacing patterns with overlapping graphic shapes similar to the contemporary work of M.C. Escher (Image 12, below). In fact, when doing research for this blog I discovered a study by Escher of the arabesque tiles of the Alhambra, a great example of contemporary artists building on and expanding the work of the past (Image 12, below).

Construction

Off the main drag, I discovered facades that had weathered badly, thus revealing the process of stuccoing the building. Similar to most countries that use traditional stucco to cover a building, yet, Segovia’s facades may be an exception because of the decorative bravado that results in grace and visual complexity. Despite the thin surface, the graphic quality is three-dimensional, allowing shallow shadows to cast on the main surface, often of a different texture and tone, showcasing degrees of lightness and darkness.

This tradition has maintained its currency, and can be found in recent interventions, although to my taste there is a of lack sophistication and elegance, perhaps simply because there seems to be a misinterpretation of scale, an almost mechanical attitude, that counters what was so well negotiated in past surface treatments (Image 13 and 14).

Conclusion

Visiting cities takes time and a trained eye in order to appreciate gestures that give an identity. Of course, each of us focus on specific ‘fragments’ that are the most autobiographical, or perhaps sometimes we discover a new and refreshing way to look at things. I, and my trusted iPhone, remain mindful of Le Corbusier’s article “The Eyes that do not See” published in 1923 as part of Vers une architecture.

Love Escher and the various optical expressions he envisioned as he worked. Your images of doors and their trim are wonderful examples of individuality, and their broadness. Well written and thank you for sharing.