The history of mirrors goes back to the first human gaze in a pond of still water, which in around 6000 BCE evolved to become the ubiquitous object that we call a mirror. To create mirrors, man started with polished stone (or volcanic glass when available), later fabricating them from various metals, finally ending with rough polished man-made glass backed by mercury. This technique was invented in Venice, which during the Renaissance held the monopoly for the production of mirrors.

Fast forward to the 19th century and the Industrial Revolution. During this time, objects of luxury previously created for the elite were popularized as they were produced in bulk. At the same time, silvered-glass mirrors were invented. Today, we have sophisticated technology in many specialized disciplines that allows us to to discover galaxies far beyond our physical reach, thus continuing man’s desire to innovate.

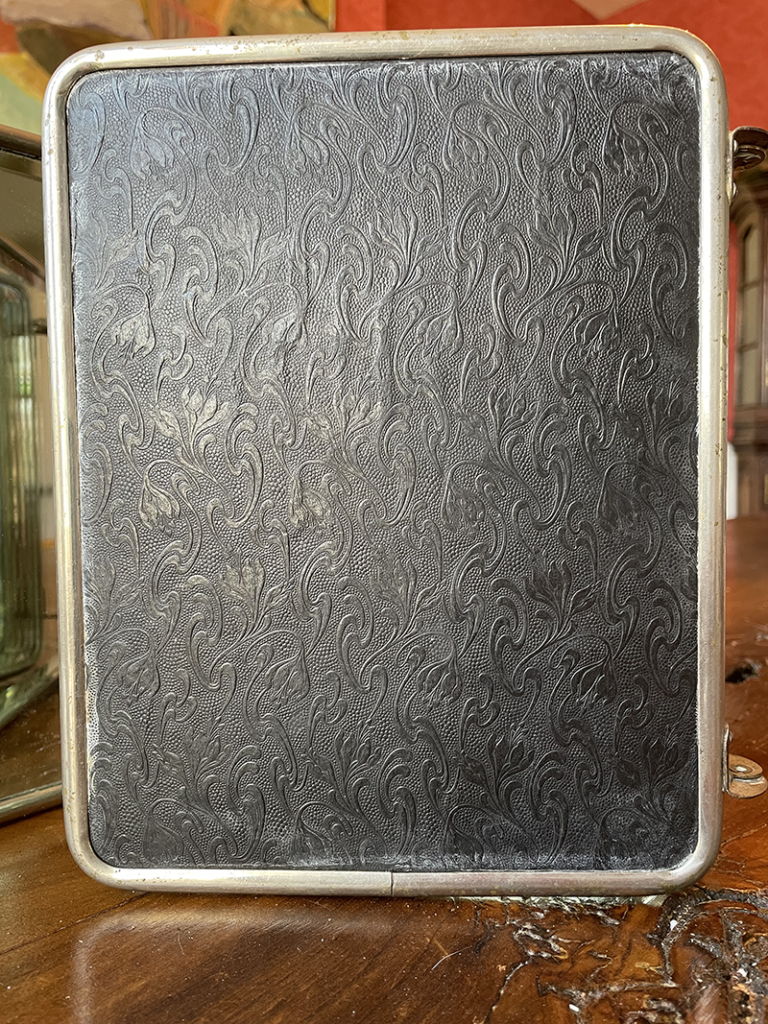

Concurrent with these advancements in technology, since its inception, the mirror has also served as a focus of lust, beauty, and vanity, deception or trickery, a place where truths and illusions are reflected. Or, may I say, an object to be avoided, where shallowness and fear may be revealed. These themes have been extensively depicted through symbolism and allegory in painting (Image 1, above).

Tri-fold mirror

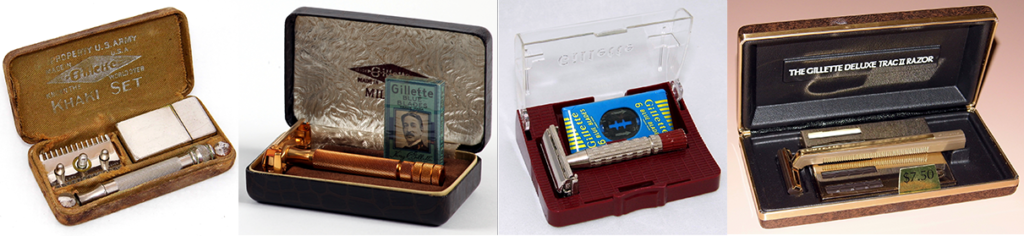

The 20th century tri-fold plane mirror (there are also spherical, convex, or concave mirror types) that is in my possession, may have served for these themes; however, its true purpose was for a barber’s shop and the perfect grooming of a gentlemen (Image 2, above). Now, after some research, I have discovered that this mirror may have also functioned as a military field-gear shaving mirror presumably used by an officer as part of his solder’s kit. For the moment, its true purpose (barber or military) is debatable.

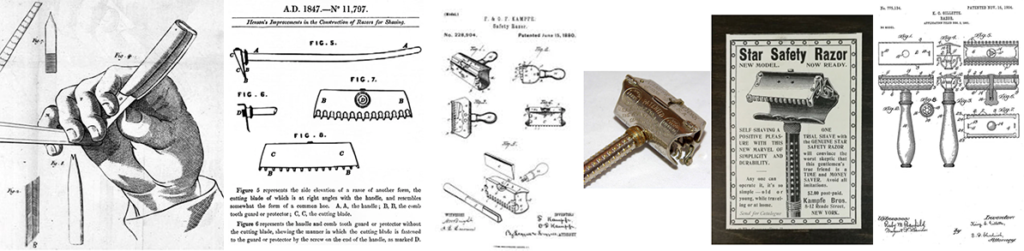

These portable mirror types came about after the mid 18th century invention of the safety razor by Frenchman Jean-Jacques Perret (Image 3, above). This new razor was by today’s standards still a rudimentary object that provided a three-sided wooden guard over a traditional straight razor; a blade that needed constant honing by a cutler. Safe to a certain degree, this straight razor is today dubbed a “cut-throat”! In the late 19th century, King Camp Gillette improved on the Kampfe brothers’ razor by patenting the prototype of today’s removable and disposable razors.

The safe(r) razor rapidly impacted the profession of expert barbers due to a surge in at-home self-barbering. Since tri-fold mirrors seemed to also have been designed for the military, it is noteworthy to mention that during WWI, “Gillette secured a US army contract, putting a disposable razor in every soldier’s pack. It changed the world of shaving instantly.” The next major advancement was the 1930 patent by the Schick company: dry shaving with an electric razor, thus ushering in a more eco-friendly shave.

There were many aspects of Gillette’s improvement on the Kampfe brothers’ razor, all aimed at comfort: an industrial approach to the manufacturing of blades from thin sheet steel; greater safety due to a predetermined blade angle (today there are multiple blades, up to six with a pivoting head); a more ergonomically friendly holding grip; and, once disposable, increased hygiene as part of the daily ritual of grooming.

We have conquered comfort, but I believe that there ought to be a next design industry revolution, one that resolves the question of environmental sustainability so that prepackaged disposable blades and contemporary shaving instruments will no longer be discarded when they are not razor sharp. Per the US Environmental Protection Agency “billions of plastic razors and refill blade cartridges get tossed in landfills each year.” Knowing this, planned obsolescence can no longer be part of any design of objects or architectural buildings! This is why, in recent years, there has been a comeback of the double-edged safety razor.

Various tri-fold mirrors

During my research, I found various models of the tri-fold mirror. Some feature small metal extensions at the bottom to allow the mirror to stand elegantly on a surface. Mine does not have legs, but when opened in the form of a shallow triangle, the mirror stands by itself (Image 2 above, and 5, below).

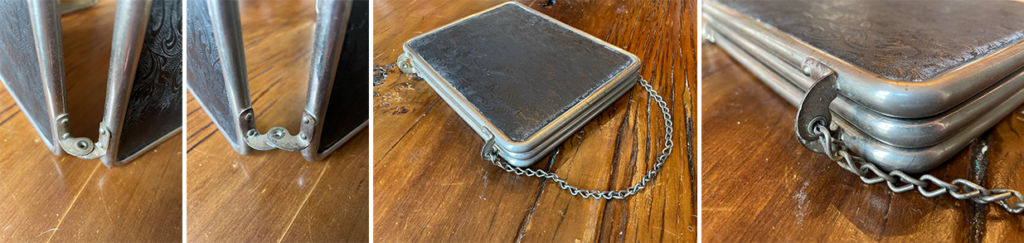

Another key feature is the mechanism joining each mirror. Between various mirrors, I found three types of connections, each simple and elegant, which allow the individual mirrors to join through this curved hinge so that they can open or fold close into a compact piece. This was important for the mirror to be portable and/or to be easily stashed in a pouch (that I do not have), satchel, or held by hand (Image 6, 7, 8, below).

The first example (Image 6, above) has hinges fastened to the top of two mirrors, while in the second example (Image 7, below right image) the hinges are attached to the sides of the mirrors, connecting them by a half-concealed hinge. This version seems less elegant then the first one, and perhaps more susceptible to break while opening the mirror; pulling might possibly damage the delicate rounded frame. The mirror that I have (Image 8, below) addresses my concerns in the second example, while still featuring hinges attached on either side of the outer mirrors.

A last element of importance is the use of two slightly different hinges allowing the mirrors to fold on each other, letting the first flap fold over the central mirror while allowing the second flap to nestle over the first flap. A subtle change in the width of the left and right hinges enables both side mirrors to fold inward, creating a perfect compact element when closed (Image 8, below). This mechanism takes into account the width of the frames, sequencing the opening and closing of the mirrors.

Compared with other mirrors, the refined hinge system suggests that my mirror is vintage 1950s rather than early 20thcentury. Nevertheless, it is still an object of great beauty and has multiple uses beyond serving as a shaving mirror (Image 11, below).

Construction and backing

Each section of the tri-fold mirror is set in a tubular nickel frame that is fastened at the bottom by two screws. The beveled edges give a visual softness and makes the mirror easy to handle. The backs have a floral quilted motif that at first seemed to be leather. Yet, because leather feels soft and warm to the touch, and typically has a distinct oaky smell, these basic attributes did not seem to fit my mirror. Still not sure that mine was genuine leather—also because the embossing would have aged differently with the typical small imperfections found in leather—during my research, I stumbled on a material called Naugahyde.

Naugahyde

Invented in 1914—which predates my mirror—Naugahyde was the “first rubber-based artificial leather.” This man-made product was made from leather fibers and rubber compounds and was used in the making of handbags in the 1920s. Later, a perfected Naugahyde was fabricated from rubber-based materials and was developed for use in WWII leading to mass production in industries such as upholstery, footwear, clothing, and luggage. Based on this, I believe that Naugahyde was used for my 1950s mirror, giving it the necessary durability and beauty which earned it a place in my collection of collections.

General Information

Creator: Unknown,

Date of manufacture: c. 1950s

Materials: Nickel plated, Naugahyde, mirror

Technique: Beveled glass with rounded corner frame

Dimensions: Folded H 9.25 in, W 7.5 in D 3/8 in, and open H 9.25 in, W 23.0, D. 1” 1/8 in

Origins: Possibly France

Additional curiosities named Portraits of a collection

Images