Urban Posters in Paris, France. In most cities around the world, and in particular in Europe, public posters, placards or affiches -as they are called in France- became commonplace after the invention of Guttenberg’s printing press around 1450.

The ability to reproduce words and images on paper expanded rapidly over the next centuries and, since the 19thcentury, the idea of advertising in the public realm has been integral to the identity of most urban environments.

Advertisements

Over the last two decades, digital signage has forcefully replaced many traditional paper panels, especially those aimed at the automobile driver. Prominently positioned around major arteries, large-scale outdoor billboards advertise a cornucopia of products and simultaneously inform drivers of impending traffic congestion on Paris’ boulevards or ring roads (peripheriques). Smaller digital versions of the signs are part of the pedestrian scale, morphing image into image through fading or scrolling techniques; all done silently and seamlessly in front of anxious bystanders awaiting an already crowded bus or underground metro.

Each time I visit The City of Light, I am reminded that, despite the use of modern digital signage, the plastering of walls with old fashioned posters is still alive and well. The Parisian pedestrian is fully accustomed to this dense visual landscape. The affiches are designed to catch one’s eye quickly, to convey unambiguously a message with strength and wit, be immediately understandable and, most importantly, be memorable for the passerby.

Celebrated artists

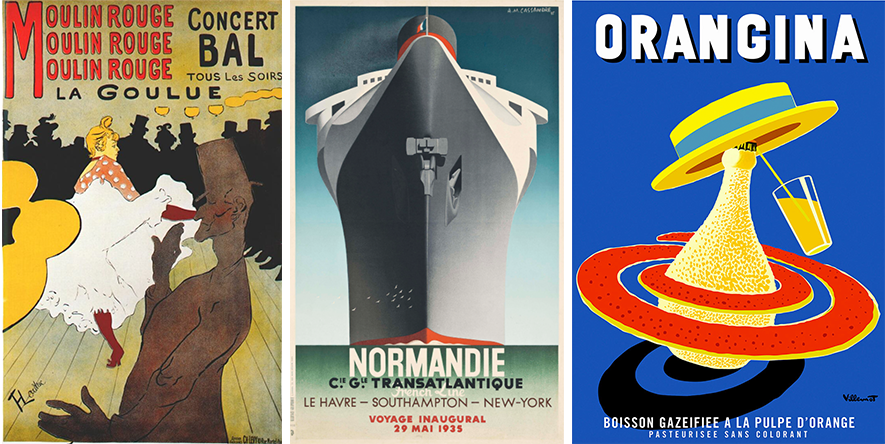

There is a robust history that traces the evolution of advertising affiches as important, yet temporary art pieces. Among the celebrated French commercial graphic artists are visionaries such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), who captured so beautifully the Belle Époque of Parisian nightlife; A.M. Cassandre (1901-1968) who advertised luxury travel through the ocean liner Normandie; and Bernard Villemot (1911-1989) who promoted French cultural icons such as the Orangina drink.

The colleurs d’affiches

The métier of the colleurs d’affiches is to layer upon existing layers, new advertisements on walls as well as on designated urban furniture or temporary construction site barriers. Armed with roles of posters, a bucket of water with glue, and a long broom, within minutes a new message replaces the previous one. New content slowly masks past announcements:

- of art performances or museum exhibitions

- of the promotion of believed to be indispensable home products

- of Happy Meal toys tied with a newly released family film, and

- of political campaign posters of long forgotten candidates.

Designed obsolescence is expected. Eventually a thick wall is created, requiring history to be removed and the publicity cycled to resume on a fresh canvas.

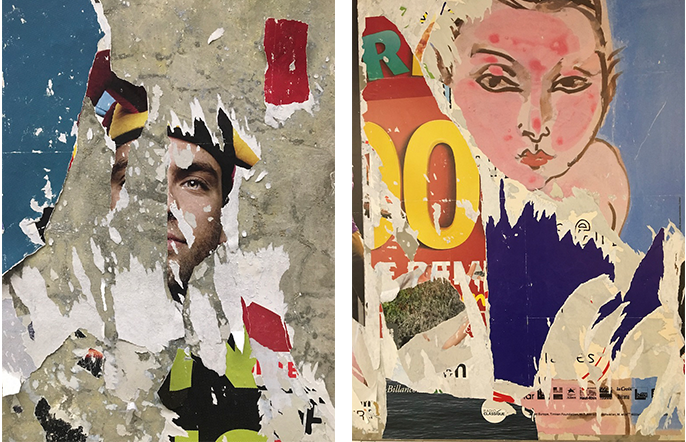

Accidental visuals

And here is where the magic starts. The removal of those layers creates accidental and unexpected visuals, allowing associations of words and images to produce new thoughts. Beneath their surface, these urban palimpsests promote an art of memory allowing past content to be selectively recombined and explored through our personal and collective minds.

At first glance, the visuals appear aggressive and violent, simply because of the tears and jagged white edges created by human gestures. And yet, our first impressions rapidly subside to a sense of awe; these fragments now captivate our gaze and slowly transform our curiosity into astonishment and delight. As French painter Amédée Ozenfant (1886-1966) once said, “Art is the demonstration that the ordinary is extraordinary.”

Self-created art

While art remains subjective and is a matter of taste, I find these self-created art pieces to be beautiful within the world of contemporary aesthetics. The accidentally created iconographies are often formally playful, and occasionally provocative with suggestive and subliminal meaning. Forms, geometries, contours, colors, textures and typographies forcefully compete with each other as no unified meaning remains.

These art works remind me of the beautiful and poetic collages of German Dadaist artist Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948). Discarded bus tickets, newspaper clippings, wrapping paper and other visual items of interest to the artist are brought back to life within a composition where each memory piece partakes in their neighbor’s story.

Among these unintended images, I find those that contain ghost-like human faces to be the most fascinating. Their faces gaze at us from the background and engage us briefly as their temporary interlocuters. With their complicity, we may now finally make sense of those irrational associations found in the windows created by paper fragments.

Simon Collat, Frontispiece of the Oeuvres badines du comte de Caylus (tome X. 1787). (fr.wikepedia.org)

Charles Marville (1813-1879), French photographer, detail of a photo depicting posters in Paris, Fonds photographique françcais -commande publique (1835-1870). (fr.wikepedia.org)

Emil Mayer, (1871-1938) Austrian jurist and photographer, photograph of a colleurs d’affiches gluing a poster in a street in Vienna, Austria. (fr.wikepedia.org)

Henri de Toulouse Lautrec (1864-1901), Moulin-rouge poster: La Goulue (Google images).

For additional images, please visit Urban Parisian street art