Le Corbusier and the horizon. Regardless of the pedagogy surrounding how history and theory is taught in architecture schools, Le Corbusier’s (1886-1965) oeuvre can rarely be avoided because it is central to the experience of modernity; especially when talking about the innovative and revolutionary architectural ideas conceived by him during the early part of the 20th century.

From the 1931 white period of Villa Savoye in Poissy (Image 1 below) to the mature output of the unbuilt project for the hospital in Venice conceived in the 1960s, I am struck by many of Le Corbusier’s urban proposals; not in a manner immediately evident, especially when analyzing them as manifestoes that took place prior to, or in tandem with his early work. Ultimately there seems to be to be an obvious complicity in his work between architecture and the locus of the city.

There was a question that nagged me for many years: could there be, in particular in his iconographical output, a relationship between his vision of a city (i.e., Contemporary City, 1925; Plan Voisin, 1925; the Radiant City, 1930; and those for South America), and the idea for a renewed European suburbia, often called a garden-city? In other words, does the transformation of the urban structure of the 19th century city—cities of stone—carry meaning regarding the future of a suburban transformation?

I was reminded when rereading several of Le Corbusier’s books, that this question was always central to his early preoccupation, and was reflected powerfully in at least two of his seminal books regarding urban issues. For the purpose of this blog, I will refer mostly to the most iconographical works within those books.

Precisions

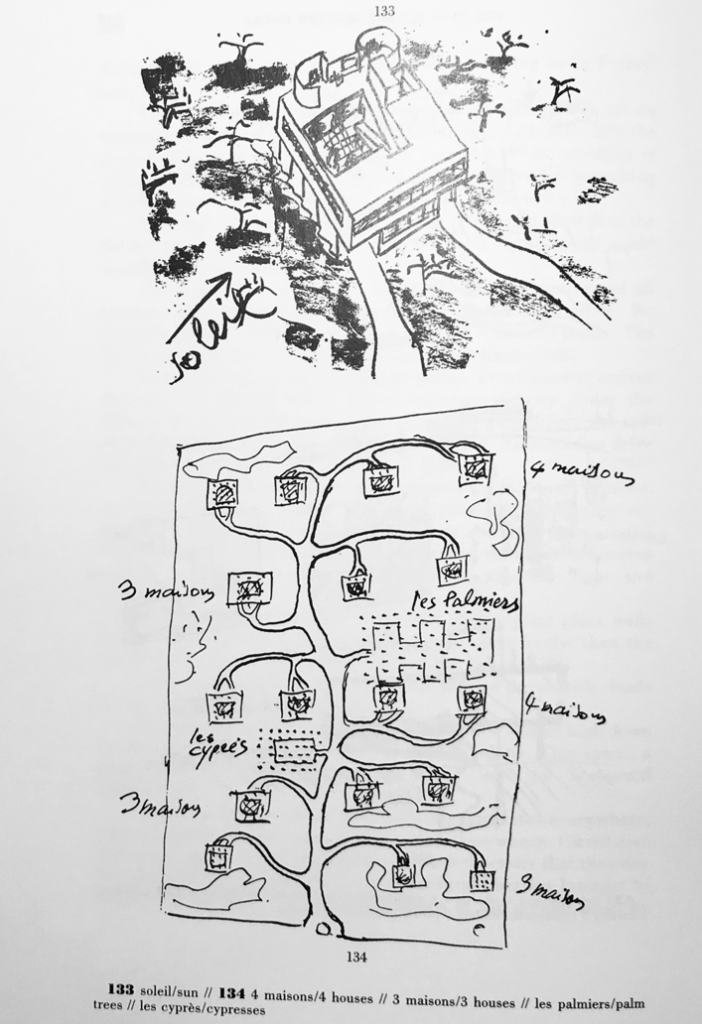

Re-reading Précisions (1930), in which Le Corbusier offers a compendium of lectures he authored during his trip to South America the year before, a combined double image caught my attention. The top sketch in this image (Image 2) represents in axonometric the iconic Villa Savoye among barren trees and a carefully orchestrated vehicular path which guides the car underneath the piano nobile, where it will come to a stop among the ground floor pilotis (columnar structure). Emblematic of the modern house, the bird’s eye view is accompanied by the word soleil (sun); perhaps not solely to contextualize the orientation of the villa to the four cardinal points, but more to anchor the building to the cosmos as part of Le Corbusier’s five points. (Image 3 below).

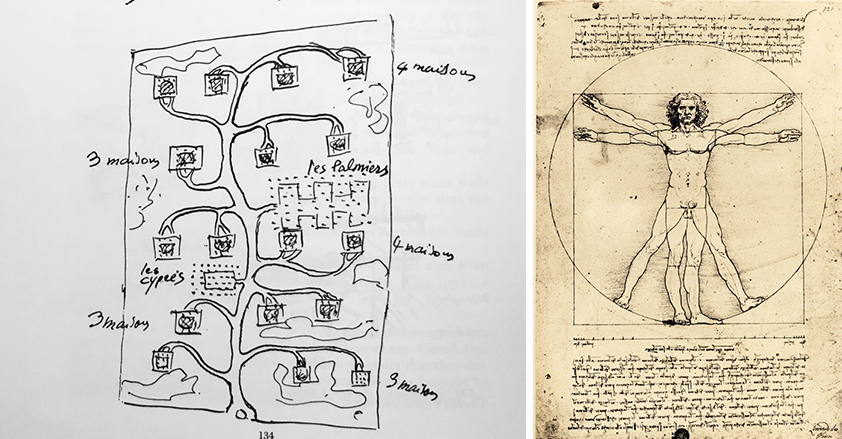

The lower part of the pair of drawings presented in Precisions (Image 4 below) astonished me. It is a site plan suggesting replicas of Villa Savoye—not as an isolated and unique object built at Poissy—but as a set of 17 identical villas on a seemingly flat site. The vertical axial composition of the sketch is emblematic of the growth of a tree where the main trunk serves as the umbilical cord to smaller branches and foliage. In this case, the tree branches connect to one, or a pair of villas. The sketch illustrates a rhythm of five (3, 3, 4, 3 and 4) sets of villas across the main tree trunk or street. I always try to find symbolic aspects in an architect’s work. In this case, the number five may suggest balance, the five senses, or the human being as described in Leonardo da Vinci’s representation of Man (the four limbs and the head that controls the limbs).

Le Corbusier’s proposed layout equates to a suburban settlement (garden-city) with additional notes regarding two species of trees: palm (the branch being an allegory of victory, and symbolism of martyrdom and longevity) and cypress (symbol of immortality). Far from our current suburban neighborhoods where many of the names given to the communities (i.e. Rabbit Run, Hamburg Place, Landsdowne) and their streets (i.e. Maple Lane) express a sense of belonging to the (bulldozed) bucolic landscape which is no longer there.

In Le Corbusier’s sketch, nature is domesticated and planned—contrary to many current communities where trees are planted haphazardly or not at all. In his plan, the trees echo the cartesian arrangement (pilotis) of Villa Savoye’s free plan, or perhaps future high-rise buildings found later (Unite d’habitation in Marseilles, 1952). In this sketch, the overall composition suggests a garden-city based on the duplication of the iconic villa.

In addition to those two areas of greenery, several free-form shapes suggest ponds in close proximity to a number of villas.

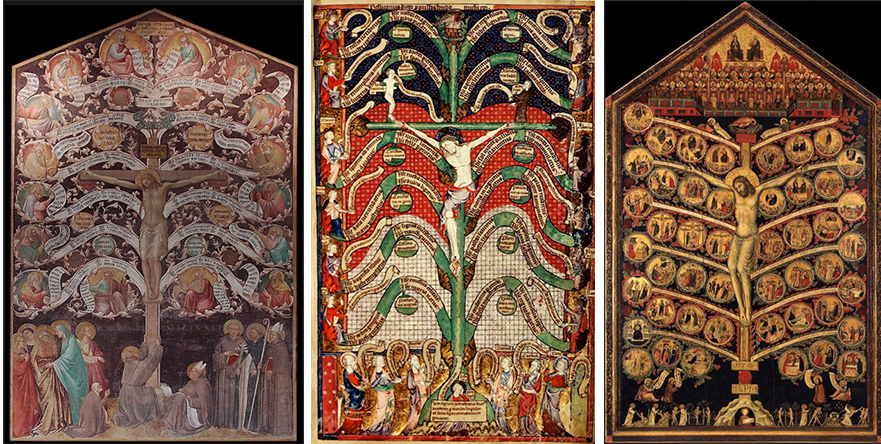

While Le Corbusier’s relationship to his faith has been debated, I cannot fail to be reminded of the formal similarity between his garden-city image and medieval pagan illustrations of the tree of life. Perhaps the symbolic nature between the tree of life and Le Corbusier’s Acadian proposal deserves additional attention, particularly because the tree of life’s iconography is deeply integrated into fine art and culture over centuries.

To my knowledge, Le Corbusier’s second sketch (images 1 & 2) is the only visual description of his interest in a suburban principle of settlement based on Villa Savoye. Interestingly, this drawing in Précisions appears among the promotion of his visionary cities for Europe and South America, including Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paolo and Montevideo.

City of Tomorrow

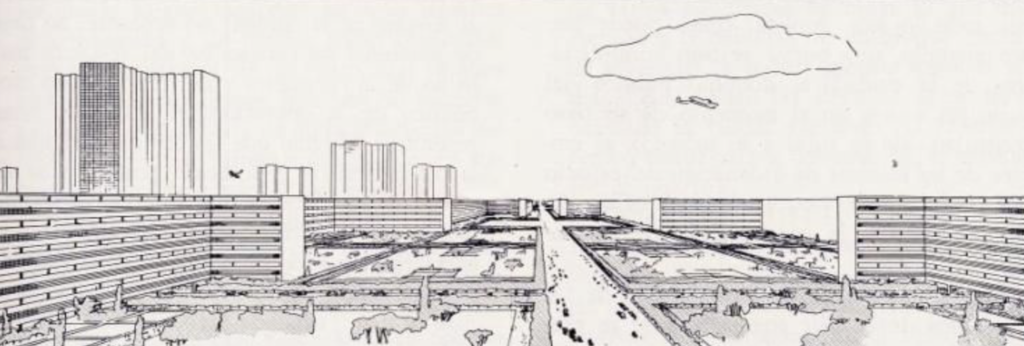

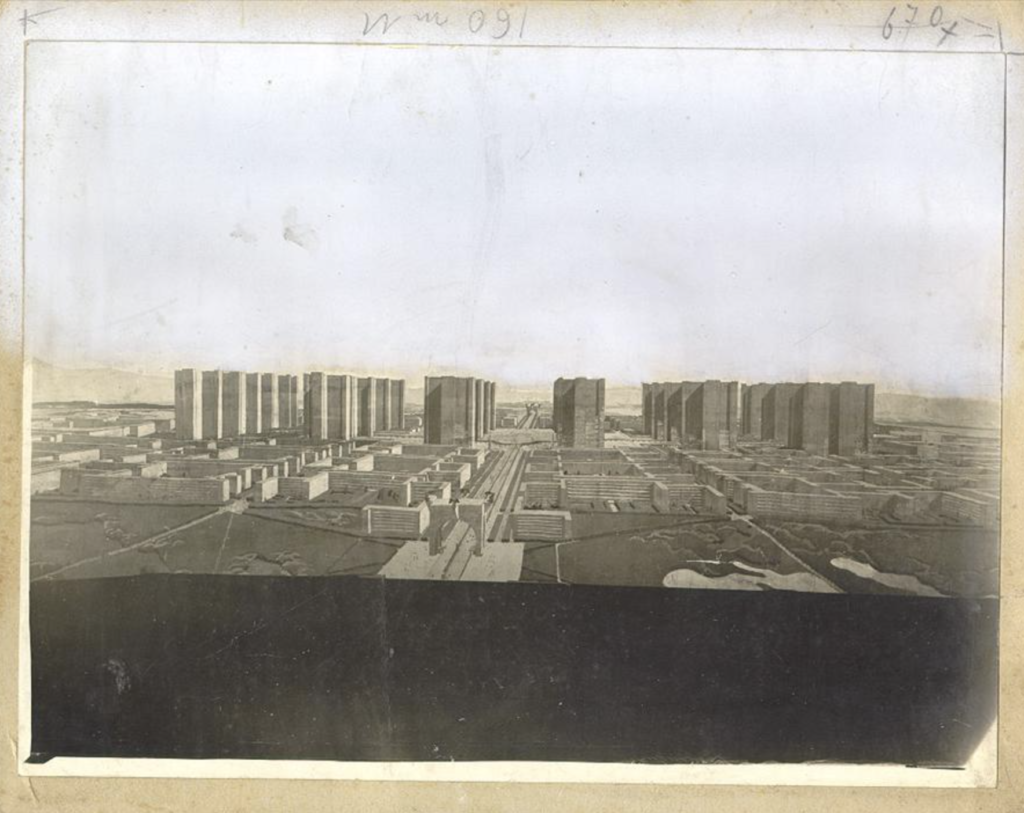

A contemporary City “Panoramic view of the city. In the foreground are the woods and fields of the protected zone. The Great Central Station can be seen in the center and the two main tracks for fast motor traffic crossing one another. Among the hills on the horizon and beyond the foliage of the protected zone can just be seen the Garden Cities.”

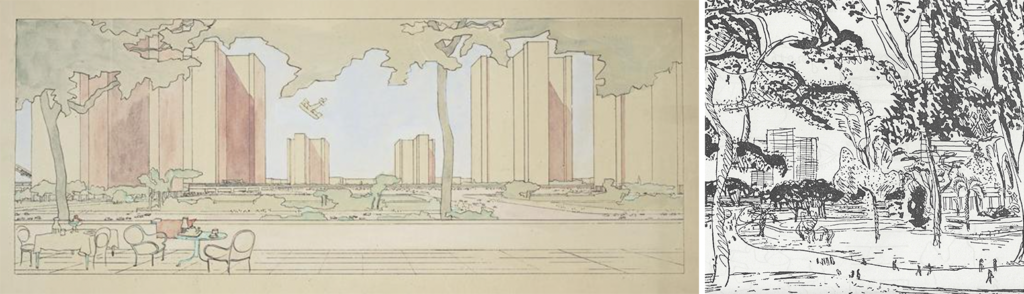

The City of Tomorrow and its Planning, originally published in French in 1925 as Urbanisme, is compelling for its overall content, however, my interest is focused on the iconography of the images. Despite the monumental and often menacing views of the city, each proposal is seen as a “city is an immense park.”

Views from within the city hint at another quality of life, genteel and domestic at times with representations of a luncheon to ease the coldness of what we had come to understand as the failure of modern urbanism. Yet, no humans interact in the view from the terrace; perhaps the empty chairs suggest everyone has left to enjoy a stroll in the park.

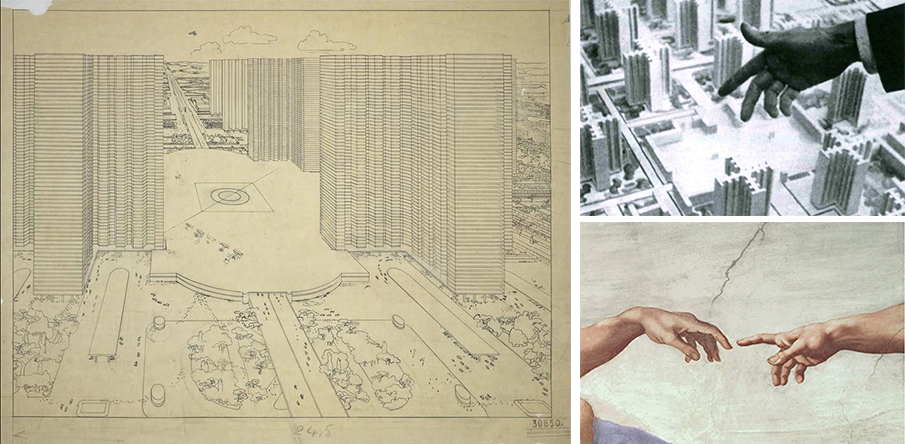

As one proceeds to the bird’s eye view of the center of the city, we understand the magnitude and scale of the “The Grand Central Station,” the new gateway of the contemporary transit hub. This important hub will have parallels later with 21st century airports defined as Non-Places par excellence by contemporary French Philosopher Marc Augé in his book Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity. These later ‘non-places’ encompass a seamless transaction between air, train and vehicular transportation, which were already proposed by Le Corbusier in the 1920s.

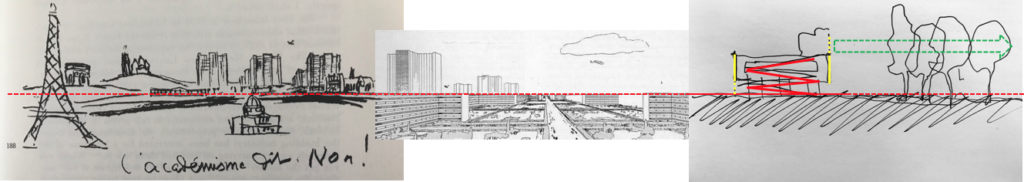

And yet, for me, what defines the intellectual beauty of Le Corbusier’s “The Grand Central Station” (Image 7) and the panoramic view (Title Image) is how the top of the skyscrapers form a perfect horizon. More importantly, this datum line corresponds to the horizon beyond the city, a place occupied by the Garden Cities, along with perhaps the promise of the proposed settlements of Villa Savoye. I find it curious and inspiring that Le Corbusier’s preoccupation with the city and the suburbs can be reflected simultaneously in the various iconographies of his utopic city proposals.

Conclusion

I have always seen Villa Savoye as a tectonic expression of the intersection of the urban life of the nearby city of Paris (expressed through the front vehicular façade), and the rural landscape (expressed through the opposing façade). Through the famous promenade architecturale, one leaves the car, walks on the ramp, and emerges onto the roof to view the panorama of the rural landscape. The house is not only a machine for living but a mechanism that sets itself apart as an instrument between urban and rural. The various iconographical horizons expressed in Le Corbusier’s drawing of his early city projects remain, for me, suggestions of a subtle expression and desire for integration of suburbia and the city.

Additional blogs related to Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier, Sanskar Museum in Ahmedabad

Le Corbusier, Immeuble Clarte

Le Corbusier, Heidi Weber

Le Corbusier and the horizon

La Petite Maison by Le Corbusier

La Tourette by Le Corbusier