John Hejduk

John Hejduk and Jose Oubrerie. During my studies at Cooper Union, I remember Dean John Hejduk (1929-2000) claiming that he had read and digested the entire Oeuvre Complete of Le Corbusier, thus suggesting that he no longer needed to refer to this seminal set of books. This blunt statement suggested that Hejduk fully understood the master’s work. And yet, I was a student, Hejduk’s proclamation perplexed me because I wasn’t sure if he was serious, or simply posturing in front of students.

Absorbing what I had heard, I was reminded of my admiration towards an America that I was discovering to be an incredibly boisterous country; one that was very different from what I was accustomed to back home in Switzerland in terms of how people shared their thoughts. Later that year, I stumbled on a project by Hejduk for the XVII Triennale of Milan (1986), and got closer to understanding the meaning behind his assertion.

The Triennale of Milan exhibition was curated by architects Mario Bellini and Georges Teyssot. They invited 18 architects and architecture firms to reflect on the theme of the domestic project. While many entries were provocative (i.e., Casa Palestra by Rem Koolhaas), obviously, Hejduk’s proposal caught my attention.

First, because I was still a student at Cooper and enamored by his stature as a revered professor and dean. He was famous for his unique pedagogy, which stood in stark contrast to that of the many European expats populating Ivy League architecture programs. Cooper Union’s innovative approach to teaching architecture was honored at the Museum of Modern Art with an exhibition entitled Education of an Architect: A point of View, with an accompanying exhibition catalogue.

Second, his pedagogy (called by the MoMA a “footprint of the future”) was complemented by a group of eminent educators and architect-theoreticians who sought international recognition for their cutting-edge work.

Cooper Union’s commitment to students, was matched by the New York Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (I.A.U.S) founded and led by Peter Eisenman. Both institutions were exceptional at this particular time and place, and forged much of my thinking as an architect and educator—as I attended both institution in the 1980s .

Triennale of Milan of art and design

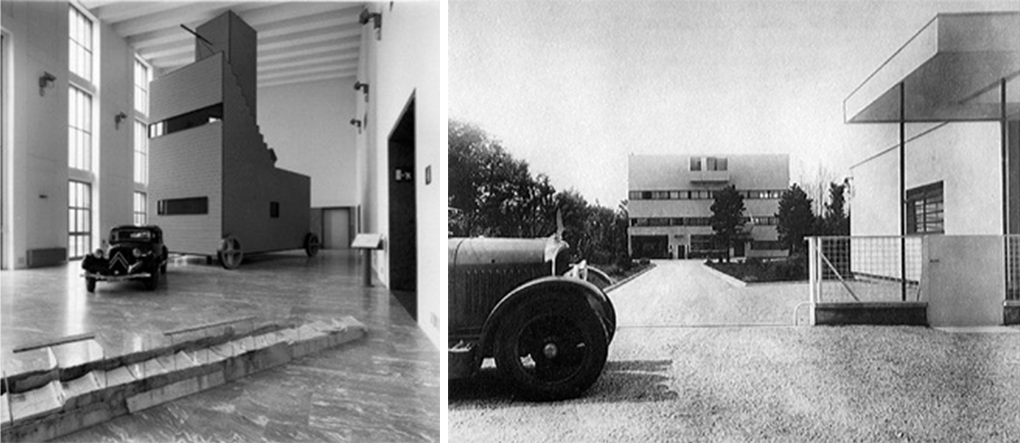

Hejduk’s project was as at first glance both expected and elusive: The legendary Voisin C7 car towed a two-story object that underscored the project’s title: The mobile House and the nomadic condition. Reminiscent of the iconic photograph of Le Corbusier’s Villa Garches—where a dialectic between machine (car technology) and house (machine for living) carried the power of architecture’s new role in society—Hejduk’s clin d’oeil to modernism, and to Le Corbusier in particular as one of the greatest European architects of the 20th century, seemed for me evident. (Image 1 above)

What was less apparent brought me back to Hejduk’s comment about no longer needing to refer to Le Corbusier life’s work. I gradually realized the suggestive power of Hejduk’s statement, that it points to the question that Le Corbusier may never have truly addressed; namely the design of a modern nomadic architecture. Thus, and what I later came to hear from Hejduk himself, was that having absorbed the Oeuvre Complete, he could now dedicate much of his design work to completing the pieces that Le Corbusier had not tackled in his own lifetime.

This attitude reminded me of German theorist Jurgen Habermas, who wrote that modernity is “The Incomplete Project.” He postulated that ideas articulated during the Enlightenment—and later by the 20th century avant-gardes—were inherited and needed to find conclusion, especially during the time of his writing, when postmodernism was raging.

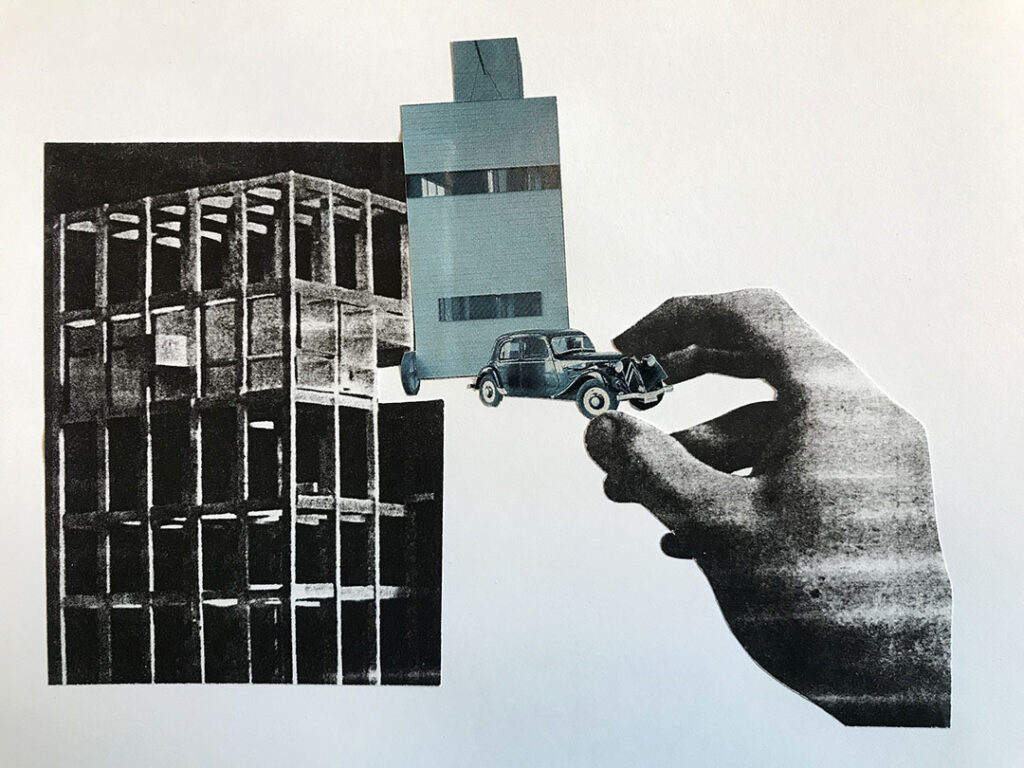

If I correctly understood Hejduk’s desire to complete the gaps identified in Le Corbusier’s work, I had now, even more, gained reverence for his life goal. And this, despite lingering questions about his later work done during my tenure at Cooper as a student; projects that seemed removed from the Education of an architect: a point of view. As a consequence, I was fascinated with my discovery and translated my thoughts into a collage which brought Le Corbusier and Hejduk together. (Image 2 above)

José Oubrerie

Fast forward to my early years as a faculty member at the University of Kentucky (UK). At that time, José Oubrerie served as Dean of the College and was one of four living apprentices from Le Corbusier’s Parisian Atelier at 35 Rue de Sèvres. Latvian architect Jerzy Soltan (1913-2005), Chilean architect Guillermo Julian de la Fuente (1931-2008) and Indian architect Balakrishna Doshi (1927 -) were the three others; the latter two I had the privilege to meet briefly.

Julian and José had worked together at the Atelier, and, after Le Corbusier’s death, collaborated on the Venice Hospital project; a superb mat-building typology (the term was created by British architect Alison Smithson) in such a deeply anchored historic city. The project ended abruptly after the political coup de grace by Venetian authorities (similarly to the unbuilt projects of Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis I. Kahn).

On the other hand, Doshi had returned to his home country and was instrumental in assisting Le Corbusier with the four projects in the city of Ahmedabad. In addition, Doshi worked with American architect Louis I. Kahn on the Indian Institute of Management (IIT) in the same city. These three key protagonists were inspired by Le Corbusier, and all three later in life made their respective and individual aesthetic contributions at the international level.

University of Kentucky

As faculty, and certainly for all students at UK, we were fortunate to have José Oubrerie take the helm of an already well-established architecture program; one that was brought forth by the vision of deans Anthony Eardley and Charles Graves.

José was a natural extension of UK’s strong pedagogy expressed through the earlier hiring of Cooper and Cornell graduates—among them the young Daniel Libeskind. Having José in an administrative role was equally important, since as a European he had no qualms claiming that teaching should be contextualized by the architect-educator’s commitment to making architecture. This dual responsibility may seem obvious today, but in the late 1980s, I remember that if you were in academia, practicing architecture was frowned upon as being an illegitimate research agenda. You either practiced or were committed to pure research, thus securing one’s academic career following the aphorism publish or perish. José encouraged a very different climate that demonstrated the need for a strong culture of construction within academia.

Miller House

In the past decade, José’s Miller House in Lexington, Kentucky, USA (completed 1991) has been the subject of extensive research, leading to recognition as one of the great American domestic structures of the 20th century. One of these studies resulted in the 2013 book Et in Suburbia Ego that surveys the Greek tragedy of the Miller House, including its story, an interview with José, analysis and influences through precedence, and a magnificent set of specifically created as-built drawings. This book was a seminal and authoritative milestone that finally did justice to this exceptional piece of architecture.

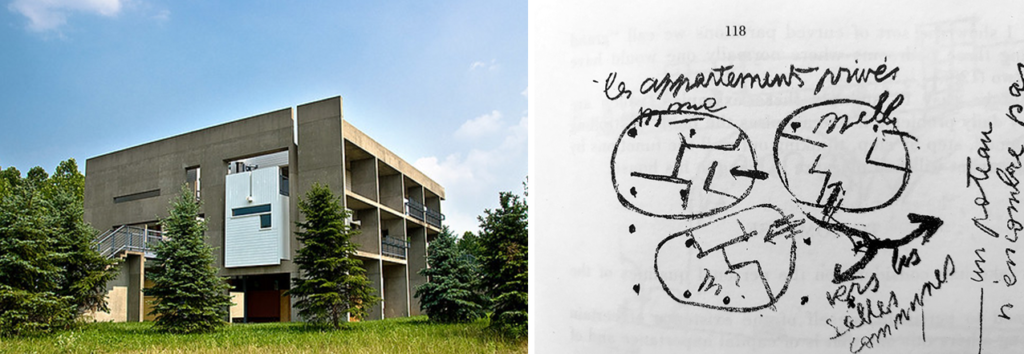

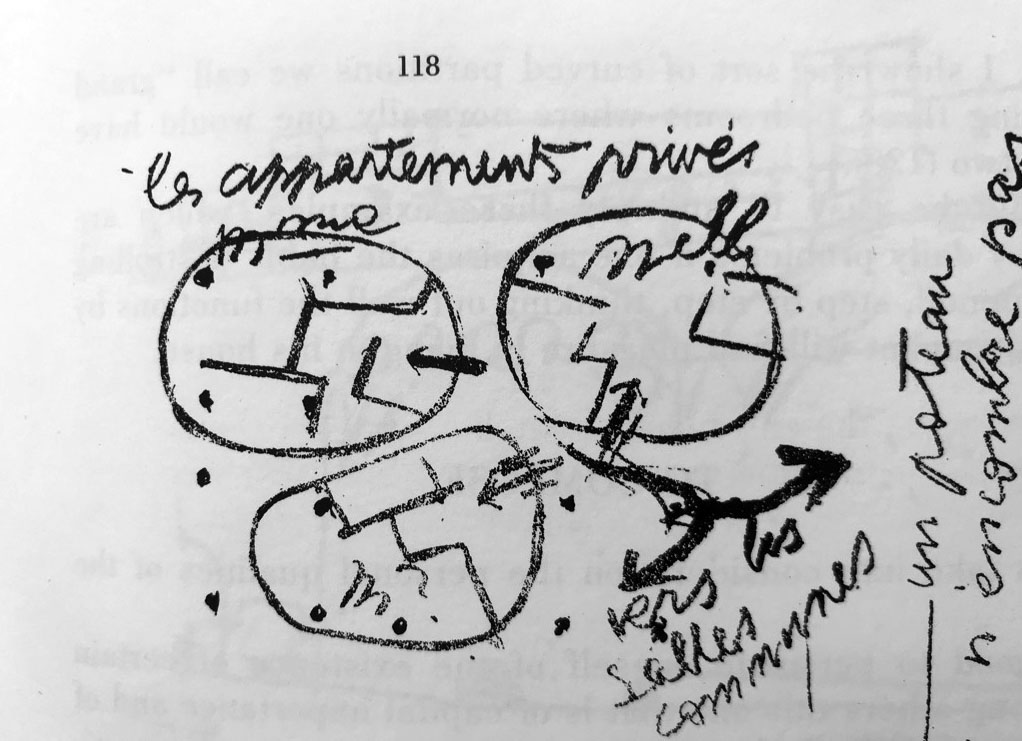

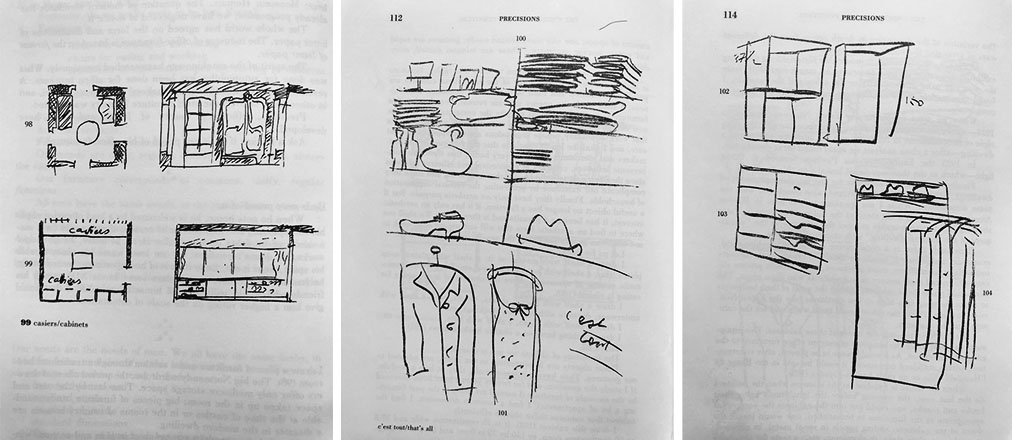

I mention the Miller House because similar to Hejduk’s contributions to understanding the work of Le Corbusier, I like to argue that for José, the Miller House in Lexington carries a similar vision of completing one of Le Corbusier unbuilt projects; or better stated, he has interpreted a very rough scheme of a tripartite house sketched out by Le Corbusier in his 1934 book Précisions. That book is a fascinating compendium of Le Corbusier’s lectures during his 1929 trip to South America, and is very revealing of his endless imagination in reconsidering man’s modern dwelling.

A model of life

The book is arranged in a non-chronological manner, somewhat based on seminal themes, and in the chapter The Plan of the Modern House under the subtitle To Circulate (Fifth lecture, October 11, 1929), Le Corbusier offer a vision of a house (Image 3, above):

“Let us go on now to another example of modern circulation inside a house. This scheme corresponds to a particular way of life; I draw only the plan of the bedroom floor (118). Monsieur will have his cell. Madame also, Mademoiselle also. Each of these cells has floors and ceilings carried by freestanding independent columns. Each cell opens by a door on a walkway along the three apartments. Once through each door one is in a complete unit made up of an entrance, a dressing room for storage of underwear, linens, and clothing, and exercise room, a boudoir or office, a bathroom, and finally the bed. Low or ceiling-height partitions, built from cabinets or not, subdivide the space, letting the ceilings through. Everyone lives as if in his own small house.”

I had never given much thought to this quote as Le Corbusier’s texts and arguments are often dense and aimed to shock and provoke. Yet, years after seeing the Miller House completed, and rereading Précisions in preparation for a seminar, I realized the implicit lineage of Le Corbusier’s description with the parti offered in the Miller House. José’s examination through his personal painterly sources, complemented by his Latin (aka, French) and now American interpretation of the master’s work, made total sense.

All the ingredients were there: a contemporary model of life for a family of parents with two adult children. The Miller House parti was “conceived as a collection of three separate dwellings within a common boundary;” and included a programmatic zoning between bedroom and bathroom, with a private stair to an upper level work studio; and offered connectivity between all three units through a complex set of catwalks above the public ground floor spaces—all defined by a series of columns.

Cabinetwork

Furthermore, preceding Le Corbusier’s quote in Précisions, we find under another chapter titled The Undertaking of Furniture, the exhortation that “The renewal of the plan of the modern house cannot be undertaken without laying bare the question of furniture.” From the simple question what is furniture comes Le Corbusier’s declaration “that in addition to seats and tables, furniture is mainly cabinetwork.” It is to be integrated through standardized cabinets with a thoughtful eye on the inner arrangement to serve the needs of the modern family.

Conclusion

When I was a student, we were taught to look at precedence in an informed manner and, in particular, contribute to a reading of a site through its cultural context. I remember one day being asked the question: “and what next?” I hesitated then, hoping I had understood the question, reiterated how I had come to the proposed solution that I believed was inventive, yet mindful of the historical implications.

With a complicit smile, my professor clarified his question by confirming my informed instinct, while asking what did I think future architects would make of my interpretation when viewing my project, my built project. If any form of continuity was to exist, I had to realize that something would come after my project, perhaps after a thorough analysis of my interpretative moves visible in the work.

Frankly, I had never thought about this important question and since then I have been mindful, especially when working professionally, that no work ends with the architect’s project. Perhaps, this viewpoint is one of the many aspects of how architecture engages memory and questions of lineage.

Epilogue

It is evident how Hejduk’s and Oubrerie’s references towards Le Corbusier’s work are inextricably intertwined. While for one, in an homage to someone he admired and never apprenticed under, there is a generosity in completing key moments left open in the master’s oeuvre, for the other, it was to have had the courage and determination to complete the master’s oeuvre through the need to reach beyond himself.

While the death of Le Corbusier was an obvious departure from the Atelier de Sèvres, I feel that José’s parcours can best be summarized by quoting Romanian artist Constantin Brâncusi: “I had to leave Rodin’s atelier for no beautiful trees can grow in the shadow of a majestic oak.”

There is a self-effacing modesty that I admire in Hejduk and Oubrerie wanting to work through their master’s language, yet linking their work to the idea of The Incomplete Project. Like Russian avant-garde artist and theorist Kazimir Malevich, “an artist cannot afford to be self-satisfied, only that man can be said to be alive that doesn’t mind discarding what he believed yesterday.

Additional blogs of interest

Lexington: a lesson in stairs (Jose Oubrerie)

Interview about architecture