Prior to talking about Raimund Abraham, let me set the context. During my year abroad at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (I.A.U.S) in New York City—an inspirational time studying under Diana Agrest, Peter Eisenman, Mario Gandelsonas, George Ranalli, and Anthony Vidler—the city became a natural extension of my academic interests and, of course, a palimpsest to discover and experience first-hand what it meant to be at the center of the world. During the 1980s, the Big Apple was a city in deep transition, and living there was nothing less than crazy, particularly relative to the tameness of my home country Switzerland.

Prior to talking about Raimund Abraham, let me set the context. During my year abroad at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (I.A.U.S) in New York City—an inspirational time studying under Diana Agrest, Peter Eisenman, Mario Gandelsonas, George Ranalli, and Anthony Vidler—the city became a natural extension of my academic interests and, of course, a palimpsest to discover and experience first-hand what it meant to be at the center of the world. During the 1980s, the Big Apple was a city in deep transition, and living there was nothing less than crazy, particularly relative to the tameness of my home country Switzerland.

Union Square Station

Image 1: Google images from left to right- Wayfinder of the MTA, photographs of the 1980s, and tiles on the wall

I remember often traveling to Grand Central Terminal by subway near midnight with my roommate Michael after a studious day and far too many bagels with smear at the hole-in-the-wall Bagel Palace. After descending into the station and passing the turnstile at Union Square, we would patiently wait for the number four or six on the quasi-deserted Piranesian platform, staring blindly at the graffiti-covered express cars on their final run down to the Brooklyn Bridge, counting the obese rats jumping from track to track, waiting for the squealing wheels announcing our train at the station’s curved platform.

These sensory experiences, heightened by the weariness of the late hour, were often carried out under the patrolling eyes of the vigilante Guardian Angels or transit police officers with German shepherds. Once we were on board, the conductor’s announcement reminded us to “stand clear of the closing doors” and often, to our dismay, added “Ladies and gentlemen, we apologize for the unavoidable delay…” (Image 1 above)

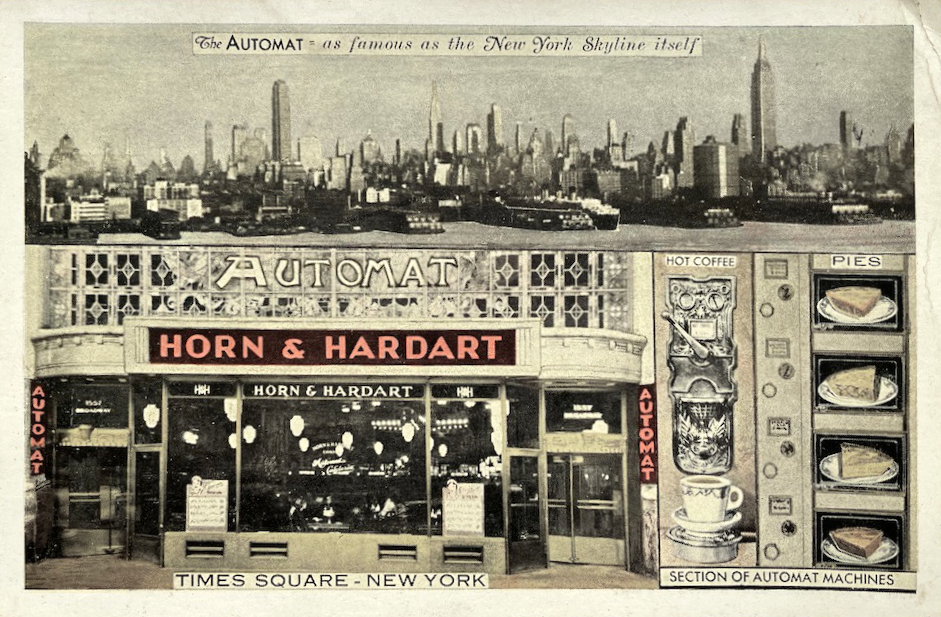

Horn & Hardart

Four stops north, we would exit the subway maze that we knew by heart, traversing the majestic and silent Beaux-Arts concourse of Grand Central Terminal, and, on the walk back to our dorm, pass in front of closed Horn & Hardart automat restaurant located on the southeast corner of 42nd Street and Third Avenue (Image 2, above). I remember being awestruck at the sight of the pristine chrome wall of coin-operated slot dispensers containing take-out salads, sandwiches, meatloaf or mac and cheese, apple pies, cakes, and various chocolate desserts; all representing what I came to know as iconic American food.

If we could afford to splurge, we would stop at one of the 24-hour convenience stores, navigating the packed aisles flooded with fluorescent light, looking for a two-quart Tropicana orange juice carton or a small pre-packaged brownie or carrot cake slathered with thick processed icing. Few words were exchanged, just a watchful look by the clerk protecting the cash register. Most of the clerks embodied the American dream, their nationalities reflecting the last wave of immigrants to the New World. At that time, many of them came from South East Asia and Eastern Europe.

New York City

While Martin Scorsese’s film Taxi Driver still reflected certain neighborhoods, Mayor Ed Koch was successfully forging the city’s future after near bankruptcy. The new prosperity brought forth a shrewdness, zest, and combativeness at all levels, and showcased that money was king as ATM machines appeared at most every corner and the wealthy made their mark gentrifying the city, opening sushi bars and galleries, and patronizing 5-star restaurants and disco clubs such as the Palladium on 14th street (which was renovated by Japanese architect Arata Isosaki (1931-2022) following the model of Studio 54).

In the area of Cooper Union on St Mark’s Place there was an explosion of uncanny street art, and, for an architecture student, the city offered endless opportunities to see material greed in the completion of questionable yet iconic post-modern skyscrapers such as the AT&T building (1983), Trump Tower (1983), MoMA’s expansion (1984), and the Lipstick Building (1986) to name but a few. Yet, the city still had its fair share of homelessness and crime, all the while struggling to overcome the AIDS epidemic, a crisis visible at every corner of the East and West Village.

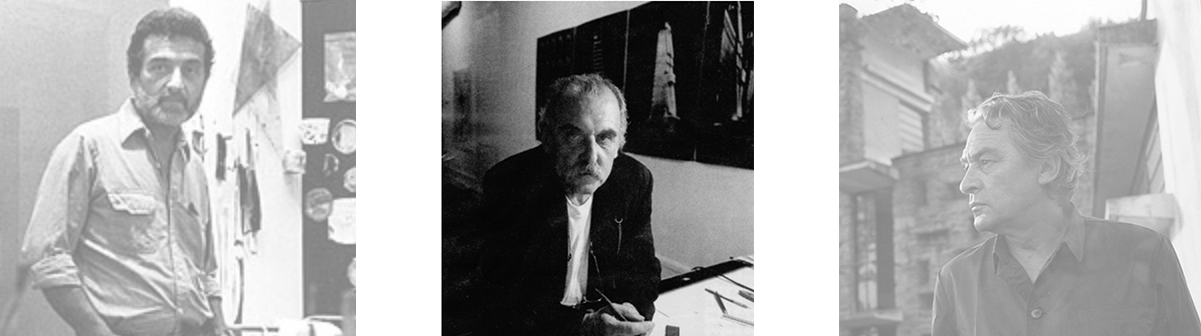

Raimund Abraham

During those thought provoking times in NYC and at the I.A.U.S., I rekindled with my former professor Robert Slutzky (1929-2005)—whom I had at the EPFL in Lausanne—and got to appreciate the educational pedagogy that Cooper Union offered its students under him and others among the illustrious faculty. Being in love with the city, I decided to follow in the footsteps of my professional internship mentor (Marc Collomb of Atelier Cube in Lausanne) who attended Cooper as an exchange student. I was accepted as one of three international students, and returned fall of 1985 to NYC to study under Raimund Abraham (1933-2010).

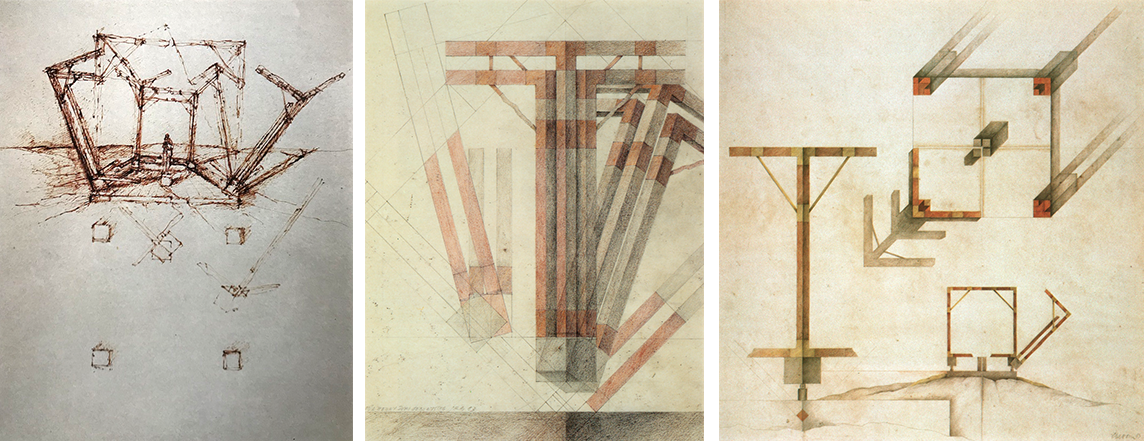

Image 3: Google images from left to right -Raimund Abraham projects for a House for Euclid, (sketch, corner detail, and section/elevation)1984

Image 3: Google images from left to right -Raimund Abraham projects for a House for Euclid, (sketch, corner detail, and section/elevation)1984

I had come to know Raimund’s work through word of mouth, research, and a curiosity towards him as he was trained in Austria and was heir to a Viennese tradition which was dear to me as I had lived there as a young child. I was particularly enamored with his drawings as he had completed few buildings at that time. Beyond the obvious attraction to a specific iconographical aesthetic—perhaps a more appealing way of drawing among the many post-modern architectural representations produced during these years—Raimund’s drawings conveyed something special about architecture.

They strayed from the typical plans and sections suggestive of construction documents. Instead, his exploratory and imaginary renderings encapsulated ideas about architecture that seemed to me archetypal, and which took me off guard with their ephemeral ambiance about the nature of being.

A question of drawing

Similar to the drawings of utopian architects such as Boullée, Lequeu, Ledoux, and Piranesi, Raimund’s drawings simultaneously bridged and blurred art and architecture. Each of his beautifully drafted depictions points to the poetry of the tectonics of architecture, yet always evades a desire for resolution; an attitude that brought tension to what I came to understand as a process of becoming.

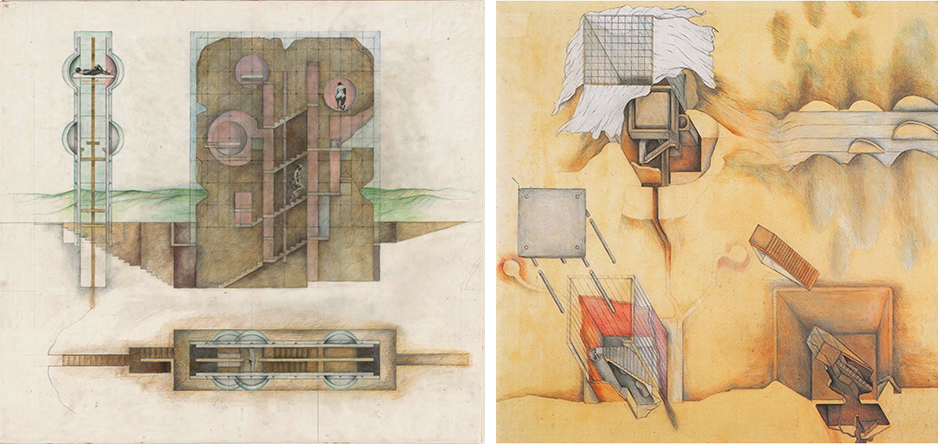

Image 4: Google images from left to right -Raimund Abraham’s House without rooms (1974), and 9 Houses Triptych (1975)

Image 4: Google images from left to right -Raimund Abraham’s House without rooms (1974), and 9 Houses Triptych (1975)

A drawing for me is a model that oscillates between the idea and the physical or built reality of architecture. It is not a step towards this reality and in this respect, it is autonomous. However, for me there must be latent some anticipation of the physical reality and its commemoration of the idea. In this sense, an architectural drawing can never be rendered. On the contrary, it has to be constructed so that it reveals the idea of the syntactic form through the medium of lines. In much the same way it has to anticipate the sensuality of the material through the layering of colour.

Raimund Abraham, Raimund ABRAHAM, Ungebaut/Unbuilt catalogue 1986

A question of language

Through Raimund’s drawings, I saw for the first time a contemporary architectural language that was powerful, idealistic, and visionary. Studying under him I began to appreciate the ontological act of grounding architecture to the horizon. This stand is best described by John Hejduk (Dean of Cooper Union 1975-2000) in an essay on the paintings of Robert Slutzky. John wrote that “In the discipline of architecture, architects pursue the datum of the horizontal plane. The horizontal plane is the architect’s ‘plan,’” and “The essential earth-plane datum is the architect’s prime horizontal field of action, without which no plans can be made, no building can stand, and no cities can be built. Constructors, architects, must revere the significance of the horizontal.”[1]

For me, the realization that an architectural practice could hinge on such an uncompromising position was breathtaking and encouraging. It was far from what I had experienced during my studies in Lausanne, although for me, retrospectively, the combination of both approaches has become a valued pedagogical stand through my decades teaching in architectural schools.

Unlike Robert Slutzky’s teaching that invited students to not create spaces for the sake of abstract forms and shapes, Abraham’s output “…was not drawing for art, nor to be translated into structure: it was drawing to question universal ideas of place, time and experience.”

A project without function!

I also learned that at times an architecture project could be designed without a function, but never without a site. Finding this proposition almost insurmountable, confidence in my impressions and intuitions guided me in many projects to develop tectonic interventions that in turn had the power to suggest function and a higher ideal of programmatic purpose (i.e., our studio brief under Raimund was to intervene on the site of the decaying West Side transatlantic ship piers, and my project ended up being a hospital between land and water; a position that translated in tectonic form the fragility of a patient’s physical or mental illness).

Through Raimund’s approach, I learned to seek fundamental ideas about the nature of architecture, especially those related to dwelling and those rituals, but above all, I have persistently pursued Raimund’s obsession regarding the horizon, which he cherished as a topographical place to create an architecture between earth and sky.

Since then, other protagonists have joined my interest in the vocation of the site, from the understanding of the territory of the Ticinese Tendenza to Vittorio Gregotti’s idea of a principle of settlement. Yet, in every attempt to find the vocation of the site, I am reminded of how Raimund contextualized his intervention as if he would “give back identity to the landscape,” an engagement that still leaves me perplexed in how he was able to create the role of architecture as site.

Epilogue 1

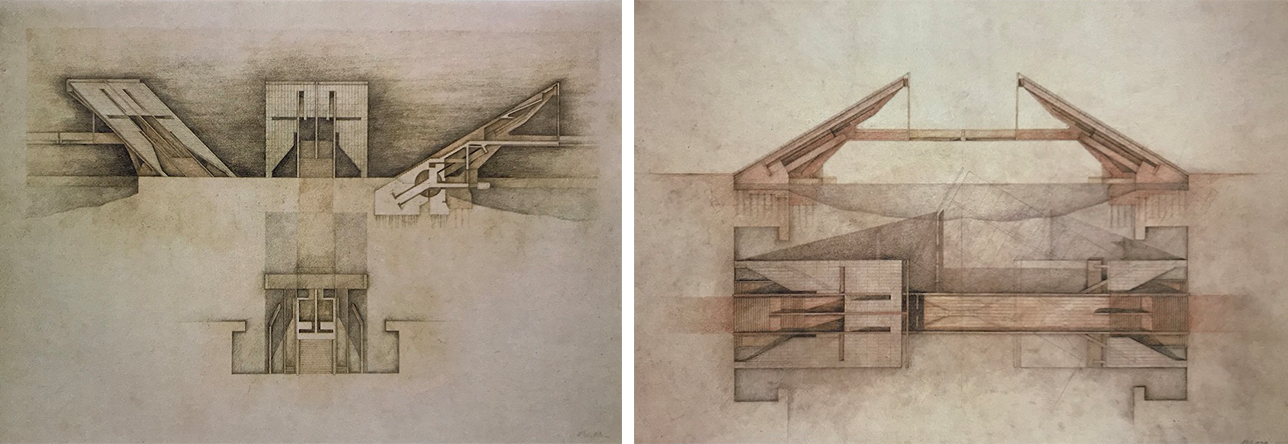

Image 5: Raimund ABRAHAM Ungebaut/Unbuilt catalogue 1986 Academia-Bridge entry project for the Biennale di Architettura, Venice (1985)

Image 5: Raimund ABRAHAM Ungebaut/Unbuilt catalogue 1986 Academia-Bridge entry project for the Biennale di Architettura, Venice (1985)

(Image 4 above, and image 5 below) Raimund was not shy about his position related to architecture. I remember meeting him in the corridor of the Foundation Building at Cooper when he had just returned from Venice after receiving the highest award for both of his entries at the 1985 Venice Architectural Biennale. I can still see him smoking a cigar, proud of the recognition, and devouring his success. As students, we were equally excited for him, and privileged to have him as an instructor.

Image 6: Raimund ABRAHAM Ungebaut/Unbuilt catalogue 1986 Ca’ Venier dei Leoni, Guggenheim entry project for the Biennale di Architettura, Venice (1985)

Image 6: Raimund ABRAHAM Ungebaut/Unbuilt catalogue 1986 Ca’ Venier dei Leoni, Guggenheim entry project for the Biennale di Architettura, Venice (1985)

Epilogue 2

Ever since moving from Canada to Europe at the age of five, I have felt displaced, not knowing where true home was. I always admired those that had a sense of belonging, which I believed to be a vital condition to become an architect. During my tenure at Cooper, I thought that to develop a practice, I needed to settle down, and thus return to Europe or elect a new place to live out my dreams.

My unease in confronting what seemed a life’s choice, was exacerbated by the sudden death of my father. One day, I took courage and asked Raimund to share his thoughts. Without hesitation, he looked at me and with his typical existentialist position, told me that I was a nomad and should celebrate this condition. From then on, I have never looked back at my life in the same way.

[1] Hejduk, John, Painting as City of the Mind (1980) in “Robert Slutzky: 15 Paintings, 1980-1984”, Exhibition catalogue at the Modernism Gallery, San Francisco 1984.

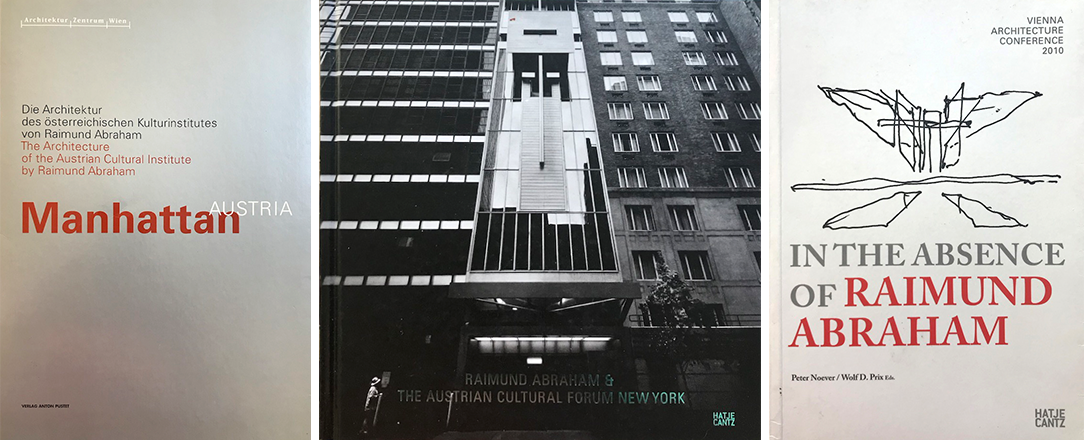

Image 7: Raimund Abraham Austrian Cultural Forum New York City 2000 (author’s collection)

Image 7: Raimund Abraham Austrian Cultural Forum New York City 2000 (author’s collection)

Image 8: Raimund Abraham Austrian Cultural Forum New York City 2000 (author’s collection)

Image 8: Raimund Abraham Austrian Cultural Forum New York City 2000 (author’s collection)

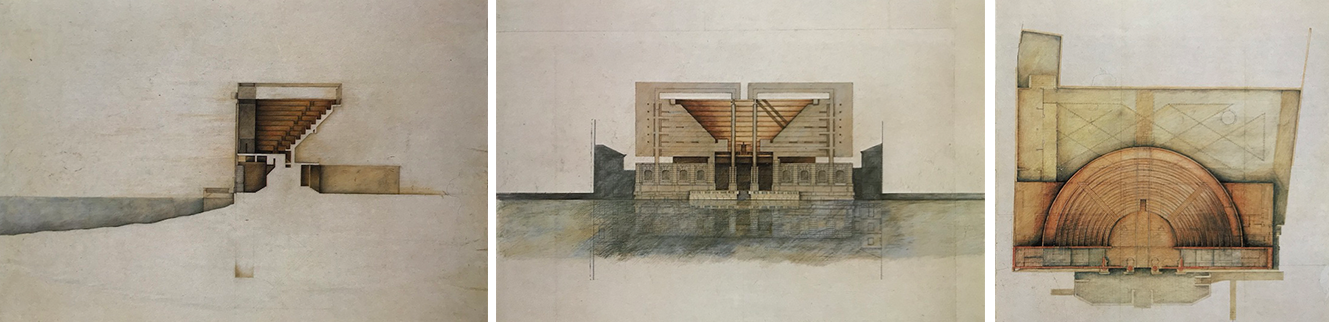

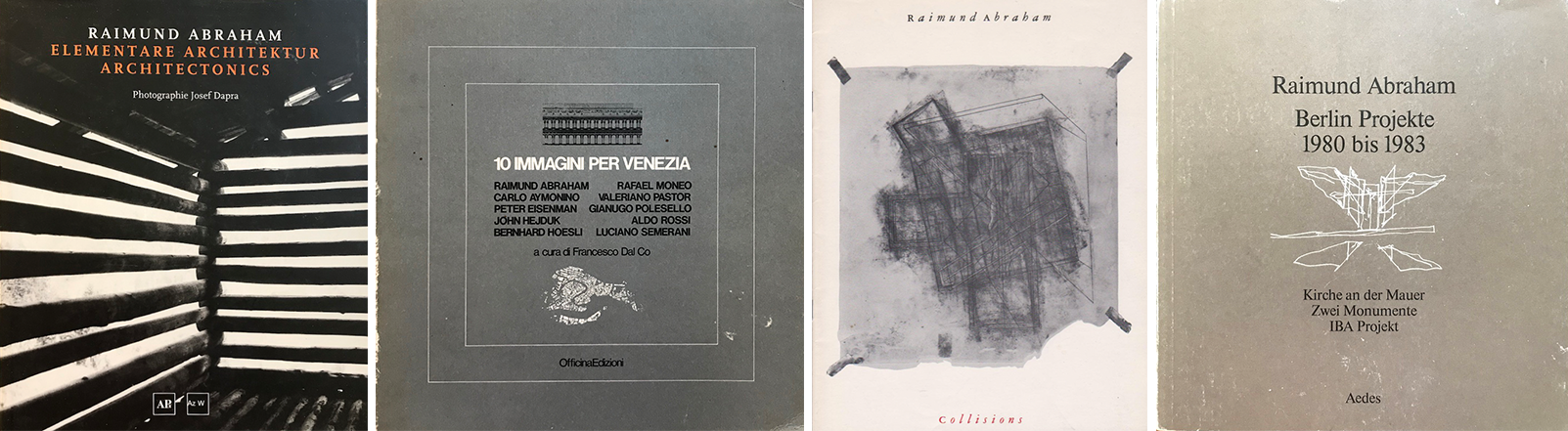

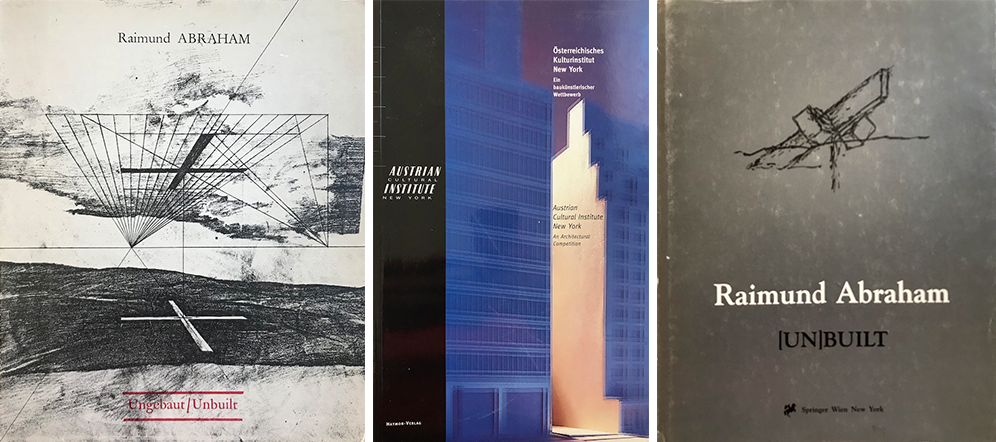

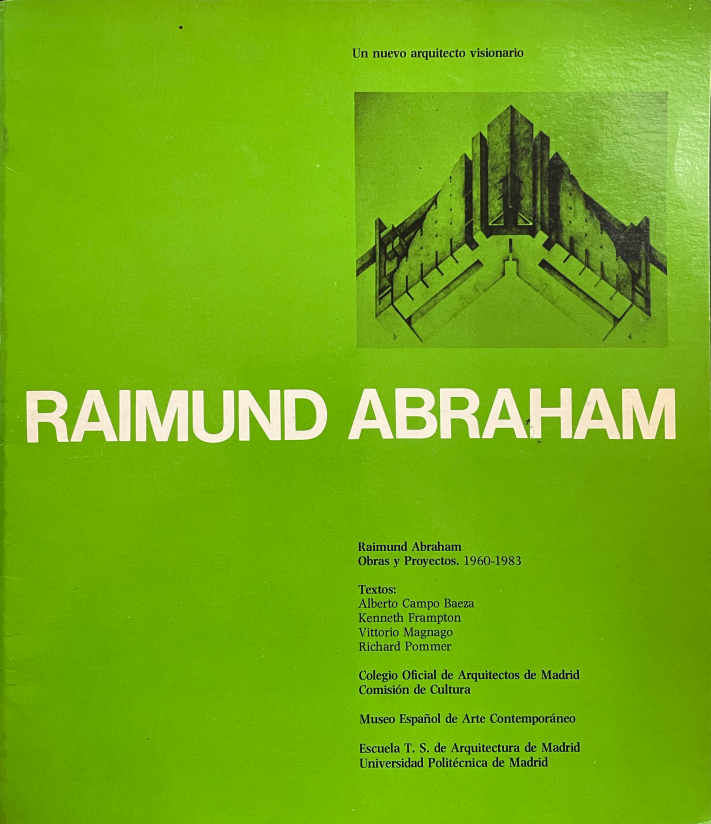

Select publications on Raimund Abraham’s work

Image 9: Select books from and about Raimund Abraham’s work: 1963, 1980, 1981, 1983 (author’s collection)

Image 9: Select books from and about Raimund Abraham’s work: 1963, 1980, 1981, 1983 (author’s collection) Image 10: Select books from and about Raimund Abraham’s work: 1986, 1993, 1996 (author’s collection)

Image 10: Select books from and about Raimund Abraham’s work: 1986, 1993, 1996 (author’s collection) Image 11: Select books from and about Raimund Abraham’s work: 1999, 2016, 2010 (author’s collection)

Image 11: Select books from and about Raimund Abraham’s work: 1999, 2016, 2010 (author’s collection)

Additional blogs of interest

Question of Pedagogy. Part 6

Robert Slutzky

The meaning of architecture -memories from Cooper Union

Interview about architecture

I had a sudden impulse to look up the Austrian Cultural Forum. I got to the page, saw the fascinating drawings and was immediately flooded with memories of my year in the internship program at the institute (IAUS) on Union Square. That was a particularly rich year at the beginning of my growth as an architect. We occasionally encountered Grace Jones on the elevator and even she looked architectural. Unfortunately, my year at the institute was its last. Toward the end of the session, our critic, Michael Monsky, informed us that the institute was closing and directed us to help ourselves to whichever books we wanted from the library. The book I’ve consulted the most in my career has been a book of ink-wash renderings titled: Fragments of Greek and Roman Architecture.

Dear Aubrey,

I just returned from teaching abroad, thus my apologies for not responding immediately. As I can assume, you know that I attended the IAUS (1983-1984) and while I did not directly have Michael as my instructor, he was seminal in our overall education at 14th street (I was the last group who saw the original IAUS premises at 40th street. Like you, I keep wonderful memories of the IAUS and was deeply saddened when they closed. I attended the auction and bought a number of items that I still cherish.

Thanks for your memories

Henri