Vienna

Eating at a diner. Growing up in Vienna, Austria, where I lived between the ages of 5 and 12, restaurant menus were mundane compared to those encountered today. This is particularly true when compared to menus found at road side dining establishments that blanket America; with their over-scaled pages and abundant choices, always followed by gargantuan portions.

During my childhood, menus were a simple sheet of neutral white paper where a select number of recognizable dishes were listed. Menus were not extravagant and had no more decoration than a simple graphic design with a couple of curlicues between food items. The purpose of the menu was clarity of reading.

As an adolescent, I came to understand that most food items were categorized as appetizers, entrée or desserts—a nomenclature that changed when I traveled to America, because in French an entrée is an appetizer and not the main course of a meal. Thus, my genuine confusion when steak frites was featured under entrée!

The Chattanooga restaurant

During my childhood, when visiting the Vienna city center, we occasionally had lunch at the newly opened Chattanooga Restaurant, an American eatery located midway on the historic Graben. At home, we enjoyed staples such as pasta, rice or pizza (still my favorite dishes), Swedish meatballs (my mother was Swedish), and traditional Austrian Wiener Schnitzel with sweet potato salad, or Semmelknödel (bread dumplings). While I enjoyed all of those homemade dishes, they became routine.

Thus, even a generic hamburger seemed to me nothing less than exotic and a fun kids’ food. What I recall most vividly at the Chattanooga was its archetypical American diner atmosphere. Narrow and elongated spatially it was outfitted with the quintessential paraphernalia of stainless-steel paneling black and white terrazzo checkered flooring, and obnoxious neon rock and roll signs.

Tightly spaced plastic covered booths provided family style seating, while a long chrome surface offered counter seating for patrons to eat while seeing food cooked in front of their eyes. Retrospectively, none of this dining experience related to the Viennese café-restaurant culture that had been in place since the Turks lay siege to Vienna hundreds of years ago.

Customs rarely change in Vienna, but the Chattanooga Restaurant broke all conventions by displaying dishes of food on laminated menus filled with full-color photographs. I guess the lamination was meant to look attractive and modern, while also a precaution to help wipe them clean when kids (me) spilled ketchup or their entire soft drink. American popular food had seemed even more glamorous since American allied forces left Vienna in 1955: hamburgers with French fries, club sandwiches, tuna melts, grilled cheese, meatloaf followed by the ubiquitous milkshakes and banana splits or apple pie. Brash American prosperity and optimism had settled into historic Vienna.

New York City

Fast forward to my first dining experience in NYC. Days after my arrival on the new continent, I stumbled on the iconic restaurant America near Union Square, a few steps from where I would attend school in Manhattan. Located on 15th Street directly in front of Fire Engine No. 14, the dining room encompassed a huge uncluttered loft space overlooking the sidewalk with large windows.

The building must have previously served as a warehouse, and towards the back of the restaurant was a miniature replica of the head of the Statue of Liberty standing proudly next to the long imposing bar. When I sat down and was handed the oversized menu, the waiter greeted me with a bright smile and words that made my day: “Welcome to America.” Beyond the casual friendliness that I was not accustomed to seeing between waiter and patron, I remember my hesitation to respond to him in my broken English. I had always wondered how to explain to him the dual irony of my second day in the States AND being welcomed to America with such panache and verve.

At the restaurant America, I was fascinated by the cornucopia of items representing staples of the 50 states. Reading the menu was like Wikipedia before its time, and while some dishes tempted me more than others, I added to my Chattanooga Restaurant experience unknown culinary delights such as Wisconsin Mac and Cheese, Boston Clam Chowder, Key Lime Pie, Memphis Barbecue, Philadelphia Hoagies, and beignets and gumbo from Louisiana, to name but a few.

Mr. Palomar

Not unlike Italo Calvino’s character Mr. Palomar—the 1985 novel of the same name whose character “is a lens employed by his author in order to inspect the phenomena of the world”—I became obsessed with learning about each new dish; I mean every American dish. In one of Calvino’s essays, Mr. Palomar visits a cheese shop, and examines hundreds of cheeses, each evoking a memory leading him to imagine fictive stories based on the origins of each cheese. Classifying, systematizing, and ordering cheese by name, taste, size, shape, flavor, smell, seeds, age and even country of origin, Mr. Palomar’s journey was about the sublimation of discovery and knowledge.

While staring at a cheese, he would imagine cows grazing on endless alpine pastures. When it was his turn to choose a cheese, Mr. Palomar returns from the thinker to the passive man and selects a mundane cheese. Perhaps this story shows Calvino’s talent as a raconteur, where Mr. Palomar is an allegory of life.

That day at America, each dish carried similar pleasures and discoveries for me. One of them was that cooking, and even more specifically, regional cooking is a “manifestation of the human soul.” While dishes result from balancing ingredients, flavors, taste and smell, cooking in general is best expressed through geography and regionalism. In France one calls this terroir, which includes “soil, climate, and sunlight” that give a specific environmental context to food; particularly when describing wine.

Denny’s menu

After gaining the freedom of mobility with a driver’s license (not only a US one, but my first one at the age of 27), I traveled by car, discovering a vernacular America that I had never seen prior to moving to the South. Living in the university town of Lexington, Kentucky, most daily amenities were readily available near campus. Prior to driving around the suburbs of Lexington, I never conceived of a fast food drive-through eatery, the personification of the American dream of replicating taste, quality, aesthetics, and service across a continent, from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Talking to a box to place my order, then moving to a window to pay and retrieve my food was alien, but so much about an American identity of mobility. This comfort from the driver’s seat of a rental car was new for me and still fuels my curiosity when traveling. I was enamored with the many offerings of highway chain restaurants that punctuated my journey from city to town. With their large and prominent signs, Cracker Barrel, Bob Evans, Lone Star Steakhouse, Shoney’s, White Castle, and even Howard Johnson’s with its adjacent motel (for me, a new word, a contraction of motor and hotel), I discovered Denny’s and its menus, and they became for me, the symbol of America’s vastness, a country’s desire for uniformity by building on its best and worst eating habits.

Breakfast

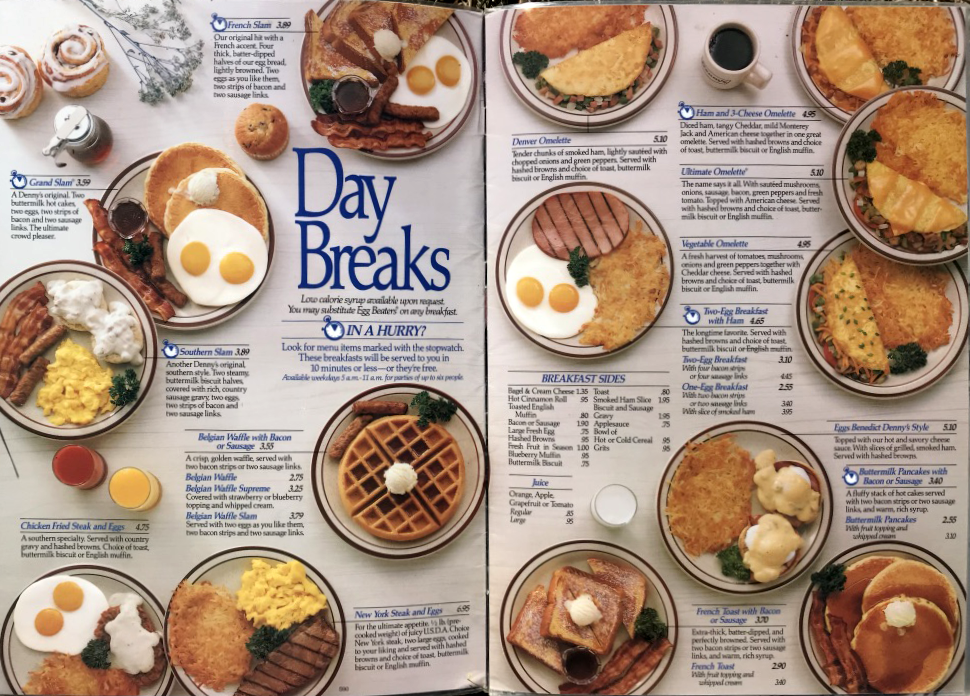

The interior of Denny’s was non-descript, with swift service and food worth its price. But, the menus, yes, the menus, they were fabulous. Like at the Chattanooga and America, any conceivable food item was presented to me on a double page.

Breakfast dishes were featured under the title Day Breaks, and were composed on a bleached-like linoleum surface. Nothing aggressive as client woke from a good night’s sleep. Each plate was composed so that the patron could identify what to expect when the dish arrived. Eggs came in various shapes and forms, which I learned could be sunny side up, over easy, scrambled, poached or served as an omelet. Well-cooked hash browns—that never measured up to the suggested crispiness in the picture—pancakes and maple syrup (called buttermilk hot cakes), French toast and the much beloved bacon, ham or sausage links (at that time another idiom new to my vocabulary). For those who had an appetite, you could order a New York steak or a Southern specialty featuring chicken and country gravy.

The final touch for each plate was a sprig of green parsley, as if to convey the chef’s attention to the repetitive production of breakfast. Scattered between dishes were biscuits, muffins, toast, sweet savories, American coffee, and a morning booster in the form of orange juice (which I learned was shortened to OJ). The choices were countless: one egg or three, mushrooms or ham and cheese, fruit topping or none, what kind of bread, choices of jelly. It was endless. I could just hear the waiter yelling the order!

Each dish was featured as a Denny’s specialty: original southern style, original hit, ultimate, or the famous catchphrase Grand Slam. Even for Mr. Palomar, Denny’s would have been a surrealistic world of choices.

Desserts

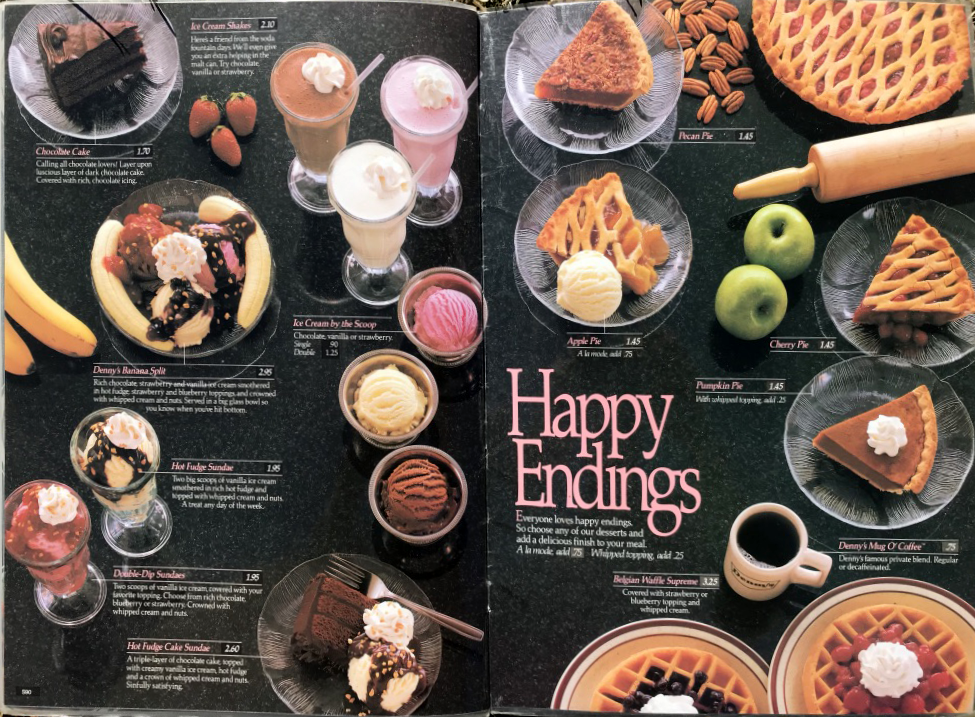

The next pages were titled Fresh Starts, followed by Sandwich Specialties, Dinner at Denny’s, and the ultimate pleasure of Happy Endings. How could one possibly contemplate dessert after such a feast or profusion of quantity over quality? Center stage on the dessert page read: “Everyone loves happy endings. So, choose any of our desserts and add a delicious finish to your meal.”

All dishes from breakfast to dessert were presented in a bird’s eye view with plates carefully composed like still lifes or tableaux of food. Inescapably, moving from back and forth between pages, as one could choose anything at any time of the day, the circular plates filled with color would start moving like balls in a pinball machine or acrobats juggling.

Epilogue

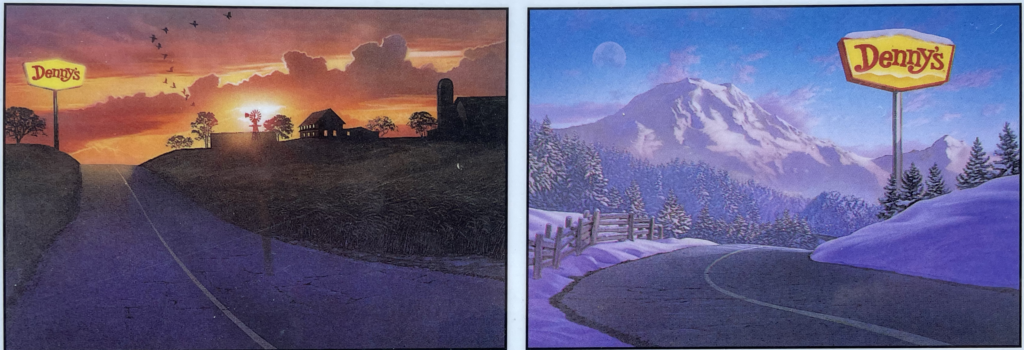

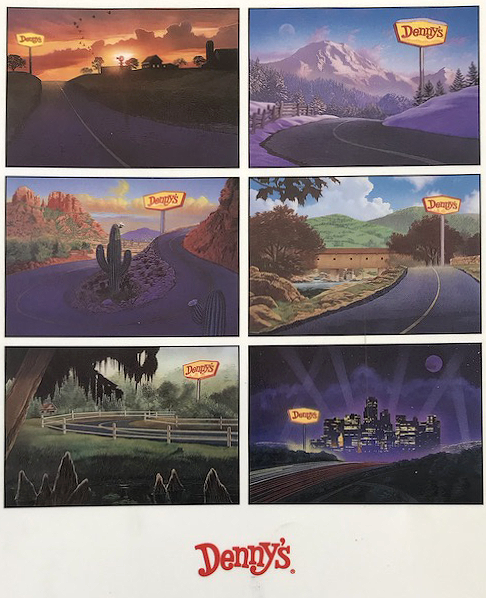

After placing my order, always with the afterthought had I truly made the right choice, I closed the menu and looked at its cover. On a white background, six images suggested iconic American landscapes. They brought me back to reality. Denny’s sign is always next to a road, day and night, through any season, and in any regional climate.

Symbolizing America’s vastness as a continent mimics the menu’s interior featuring ‘Old Fashioned Home Cook’n’. From the first image of dawn and a hardy breakfast, one traverses the country and seasons, most importantly always accompanied by the notion of a time of day, ending with a view of an iconic American city, suggesting the glamour of a metropolis where dessert could still be offered late at night.

The desire for uniformity across a continent builds on our human habits to make food recognizable across the nation. No real local foods are offered, simply good and honest down to earth American family staples; this was something that fascinated me as I discovered the beauty of the American West.