Still lifes by Ben Nicholson. Recently, I was delighted to rediscover the British artist Ben Nicholson (1894-1982) whose paintings I had so much admired while studying architecture. For some reason, I lost touch with his oeuvre despite my growing interest in the art of painting, especially the still life genre that I so much cherish. There are two reasons for my renewed interest in the still lives by Ben Nicholson.

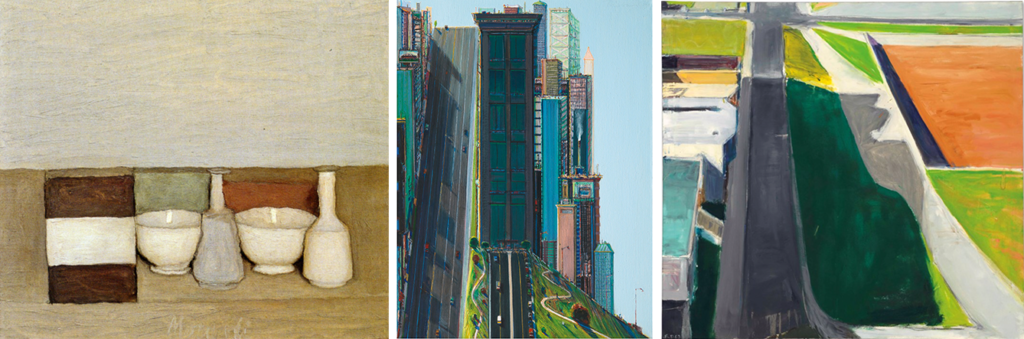

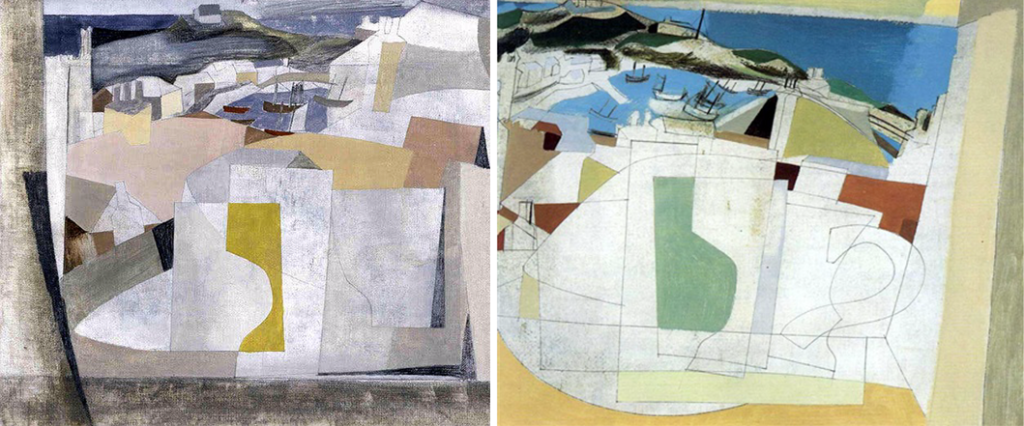

First, when encountering Nicholson’s paintings decades ago, I looked upon his work in a somewhat inaccurate manner, namely as an artist peripheral to painters such as Paul Cezanne, Pablo Picasso, George Braque, and Juan Gris (Image 1, above). In front of these pillars of cubism, I did not see him as a seminal figure in his own right. Second, through my deepening interest in painters such as Georgio Morandi, Wayne Thiebaud, and Richard Diebenkorn (Image 2, below), I discovered that some of Nicholson’s still lifes combined that genre with those of landscape and seascape. What a revelation!

Still life and landscape/seascape

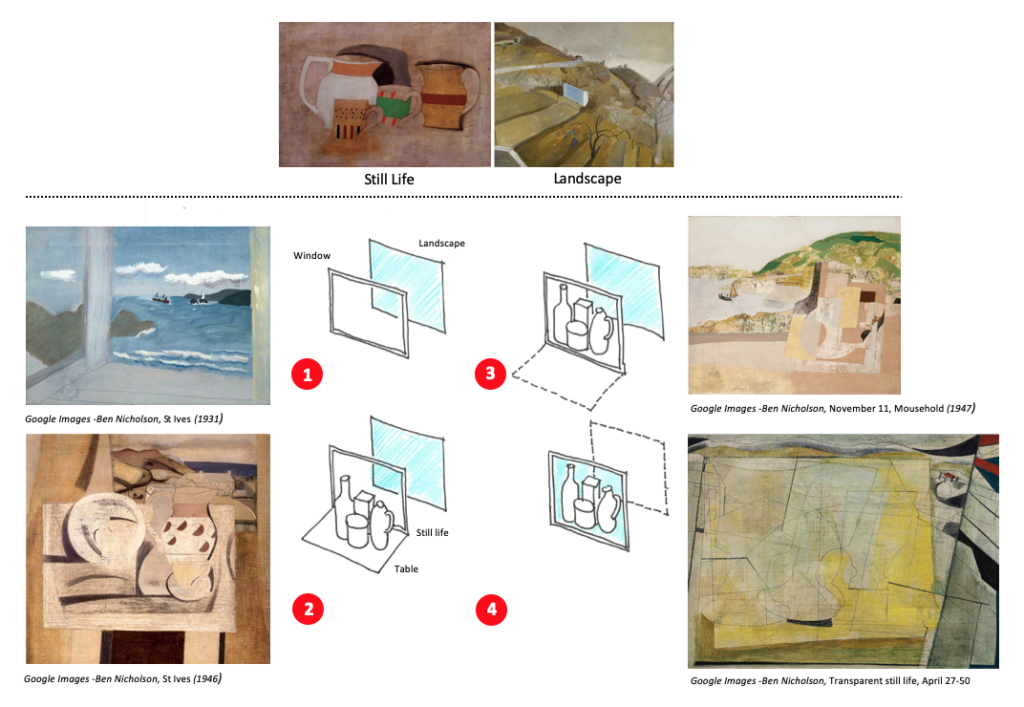

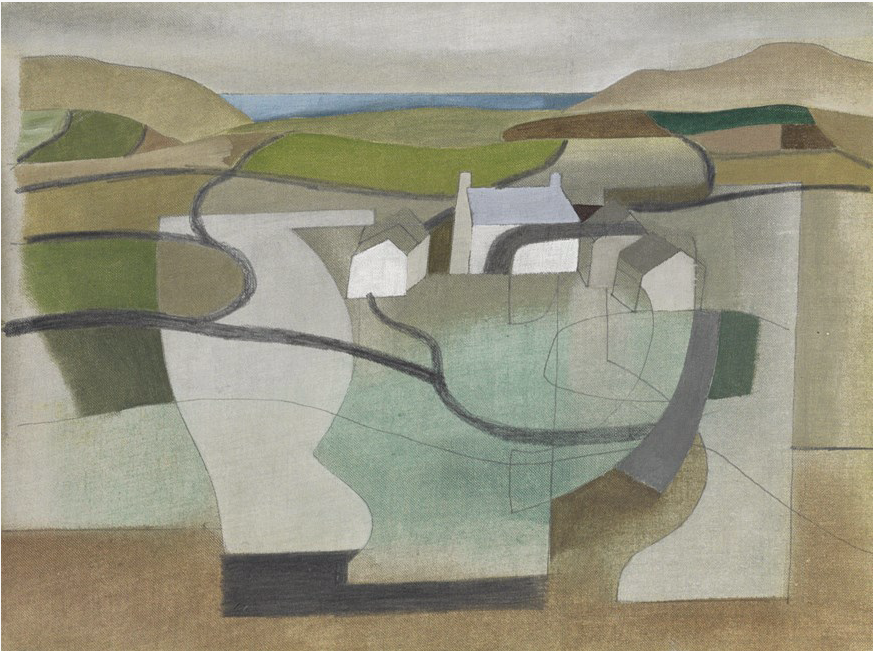

The paintings by Nicholson that I’ve selected to discuss here were completed in St Ives, Cornwall, on the far west coast of England. In them, he builds upon two traditional pictorial genres—still life and landscape. During his two decades of self exile from London, Nicholson used a distinctive approach to his paintings. In them, he overlapped, superimposed, and, most importantly to me, blurred the outlines of domestic objects—in the later ones to suggest the memory of still life groupings—into a landscape/seascape, always viewed through an open window (Image 3, below).

My fascination with Nicholson’s pictorial style results from its similarity to an architectural process—the creation of a section—when he flattens the foreground (interior still life formed by domestic objects) with the distant background (exterior landscape/seascape). In doing so, he plays with the opposition of the figurative and non-figurative, while at other moments balancing abstraction and realism in his subject matter through this personal approach to the universal and historically important pictorial themes of still life and landscape.

The resulting compositional tension found in the St Ives series, is for me, rather extraordinary, especially as each painting in the sequence matures and allows the viewer to retrace the artist’s process. Beyond the pictorial qualities that owe much to cubism, my interest is coupled with that of the modernist credo in architecture. Namely, the integration of internal architectural spaces with an outdoor environment, a constant preoccupation with many architects of the 1920s, in particular Le Corbusier (Image 4, below).

Cubism

As a student, I learned about the art movement called cubism, a style of painting that became influential in the early twentieth century. While these paintings led me to see pictorial space in a new way, I also became aware of the complexity of the spatial formulations offered by cubism that were central to understanding modernism in architecture.

At that time—and retrospectively it seems obvious as my architecture instructors were die-hard modernists—I favored a language of painting that contained abstract geometries and lines that no longer depicted subject matter in a traditional manner (meaning a Renaissance representation of space defined by a single fixed viewpoint created through perspectival drawings). What was so exciting about understanding cubism as a symbol of modernity, was the recording of multiple viewpoints within a variable pictorial space, simultaneously suggesting time and form on a two-dimensional flattened canvas.

For me, many of these cubist precepts formed an intellectual approach that was mostly self-referential play with lines, surfaces, colors, textures, and transparency, while employing techniques of collage that used simple geometric fragments suggesting flat transparent planes formed by overlapping shapes. The wonders of abstraction taught me about the suggestive power of cubist artists who were unconcerned with traditional representations of nature that offered a hermetic world view, where ideas were drawn from the subject matter itself. Abstraction was part of the idiom of a cult of modernism where, in the work of Ben Nicholson, pictorial compositions commented more on what was seen rather than seeking to represent something.

All of these new references were part of a language of painting that any young student in the 1980s would see as inspiration for their architecture designs: particularly, as with me, when your professor was the painter Robert Slutzky. Yet out of the myriad of cubist paintings I discovered, I always returned to those that carried a suggestive power of figuration (formal rather than symbolic) through domestic objects such as guitars, jugs and bottles, glasses and fruit, all typically set on a tilted table with a non-descript background (Image 1, above).

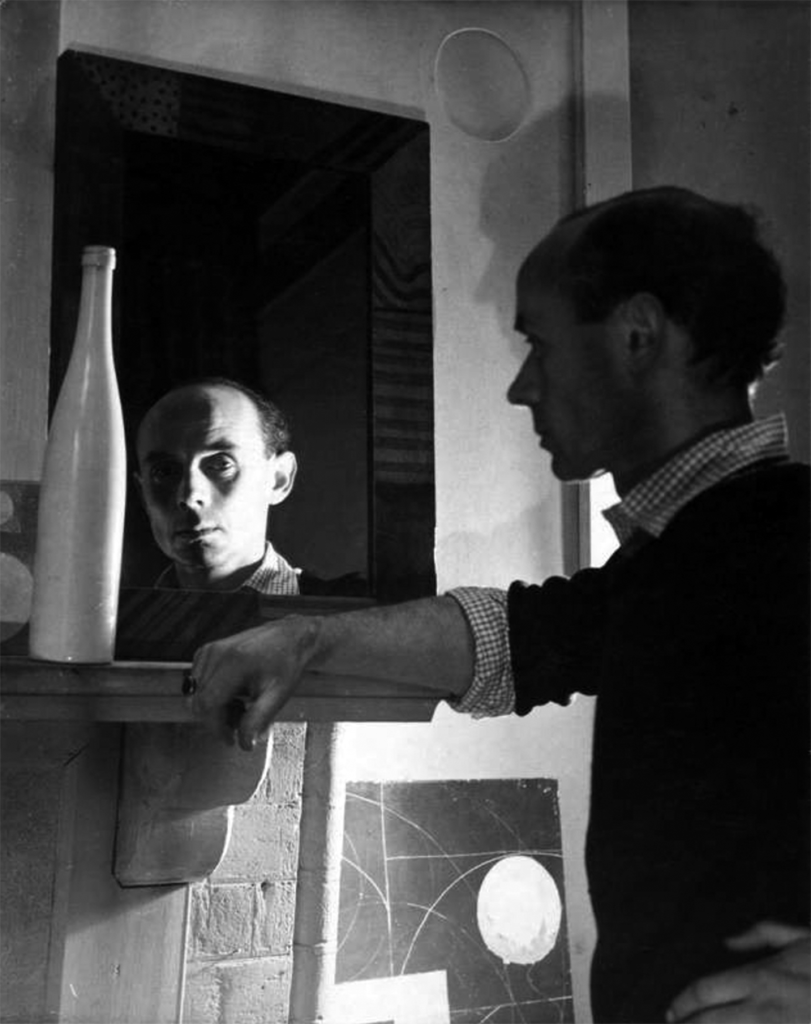

Ben Nicholson

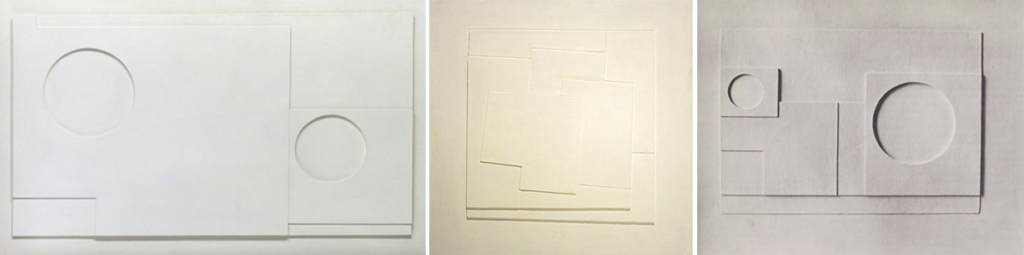

Recollecting my early interest in Nicholson’s work (Image 5, above), I remember being enamored with his beautiful white monochrome reliefs from the 1930s. Their strong geometric patterns often featured various sizes of circles carved out of squares or rectangles. To me, they were abstract architecture plans without function or program; tectonic expressions of spatial relationships between shapes, proportions, and light. Later, when becoming acquainted with his work, I became fond of Nicholson’s paintings that emulated cubist ideas through primary colors, particularly those with an earthy palette which exemplified his search for abstraction in overlapping and interpenetrating forms (Image 6 below).

New revelation

Recently, I came across a series of abstract landscape paintings done during the second World War; the period 1939-1958 when Nicholson and his family left London for the south west fishing town of St Ives at the tip of the coast of Cornwall. Prior to Nicholson’s refuge from an imminent war, St Ives had gained an identity as a thriving artist’s colony: “for a few dazzling years this place [St Ives] was as famous as Paris, as exciting as New York and infinitely more progressive than London.”

St Ives was at the height of its fame from the 1920s to the 1960s, a period which is known as the St Ives School. (The sculptor Naum Gabo and Dutch painter Piet Mondrian also lived there.) In this secluded and rugged Cornish peninsula, light was a source of renewed inspiration, and Nicholson returned to painting landscapes, tackling traditional subject matter in a modernist abstract way.

The merging of still life and landscape

Through my research, and closer look at Nicholson’s progression during his stay in St Ives, I better understood his process, and his reverence for Picasso, Braque, and in particular Gris—although Gris was not much mentioned during my research as he seemed during his lifetime less appreciated as a radical pioneer of the cubist revolution, thus critics omitted, at least to my knowledge, Nicholson’s reference to his pictorial compositions. Perhaps additional research would attempt to reconsider Nicholson as having a more meaningful and deeper relationship with Gris. I will include select paintings by Juan Gris to compare and contrast with Nicholson’s work (Image 7, above).

Nicholson’s Evolution

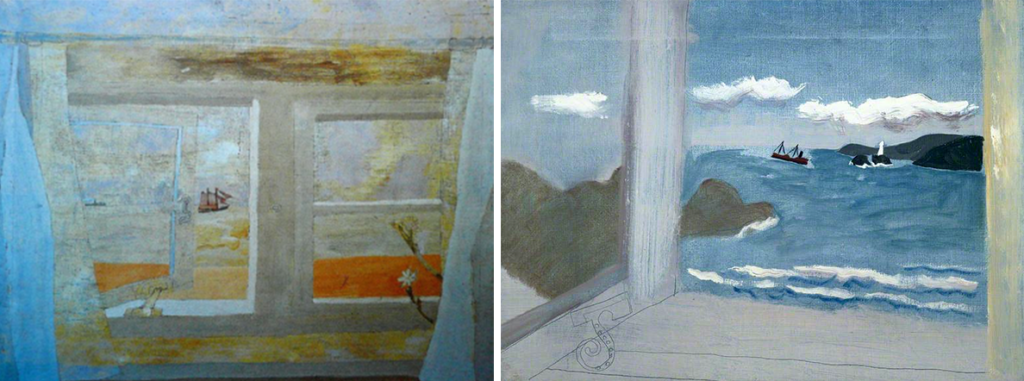

What I marvel at in the coastal scene paintings completed in Cornwall, is that Nicholson brings a new creativity and depth of connection between classical still life and landscape. He takes his earlier cubist-inspired compositions of domestic objects and places them on stage in front of an open window that frames a landscape in the background: a paysage that will eventually become integrated with the still life (Image 8, below).

In the St Ives series, Nicholson begins with rather naturalistic views of the landscape—although I am intrigued by one of his untitled works (Image 8 below, right) where we see a dramatic progression in his viewpoint. Here, the window frame reflects the landscape, thus suggesting a continuity between window pane and exterior. This flattened the reading of the composition.

Nicholson will proceed in a future series to include a cubist inspired still life—typically expressed in the foreground—with the landscape as background for his composition. At this stage, the window is merely suggested, although the still life and landscape remain somewhat separate. In the painting St Ives, 1946 (Image 10, painting to the right and both paintings in Image 11, below), there is a suggestion of blending the foreground with the background.

Nicholson’s further iterations set the still life directly within the landscape. In these examples (Image 12, below), the still life is almost depicted as an alien object, and with the artist’s choice of color and expression of light in the overall composition, the distinction between still life and landscape begins to compress and blur. A further progression depicts the inside domestic realm (still life) and the outside public world (landscape) as nearly one, although partially recognizable through the treatment of a foreground and a background (Image 13, below).

The final act

Nicholson eventually developed a complex armature in his paintings, where edges and suggested geometries of both genres dissolve and are absorbed into an abstract panoramic composition (Images 14,15, and 16, below). The flatness of these paintings is characteristic of the synthetic period of cubism, especially in the work of Juan Gris, as well as the complex information found in architecture drawings that contain the sectional cut, the projection of information pertaining to select foreground and background spatial conditions.

The spatial fluidity between his traditional still lifes and landscapes of the 1930s, transforms into Nicholson’s calligraphy of the landscape, a handwriting of lines, shapes, forms, and geometries of a new abstract paysage. Lines skate through the composition, making the textured landscape and domestic objects indistinguishable as self-referential formal strategies; perhaps a pictorial way of reengaging with the avant-garde of Paris and New York as Nicholson prepared to return to city life in London.

Conclusion

Of all of Nicholson’s mature compositions done at St Ives, there is a painting that stands out for me as critical to the sequence we just looked at (Image 17, above). In this painting, the atmosphere is naïve, the composition is overly simple: a foreground with two rudimentary houses linked by a wall parallel to the canvas. In the distance, is a view of the harbor and a settlement of toy-sized town houses. The left house features two openings: a bold red ochre door that is ajar, tempting us to sneak into the house to view the still life composed on the interior table, one that we have already seen through the window.

There is rich ambiguity in this painting, where a still life is presented through a window. This becomes in his later work, the foreground of his composition. It is as if the artist anticipated a reversal of roles, where initially the still life was seen as a background only to then serve as the foreground, ending as a seamless dialogue between interior and exterior, where cups, vessels, pitchers, and glasses mesh with the landscape through lines and geometry. The landscape can be a cup, and the jug the topography of cultivated plots of land.

A fitting end to this investigation and certainly not the end of my fascination with architecture and painting.

Other blogs of interest on painting:

Hubert Robert: Painting as a source of knowledge

Simone Martini: three principles of settlement

Le Baron Tavernier: a cafe terrace in the middle of the Lavaux vineyards, Switzerland

Architectural Education: Robert Slutzky. Part 2

Edward Hopper