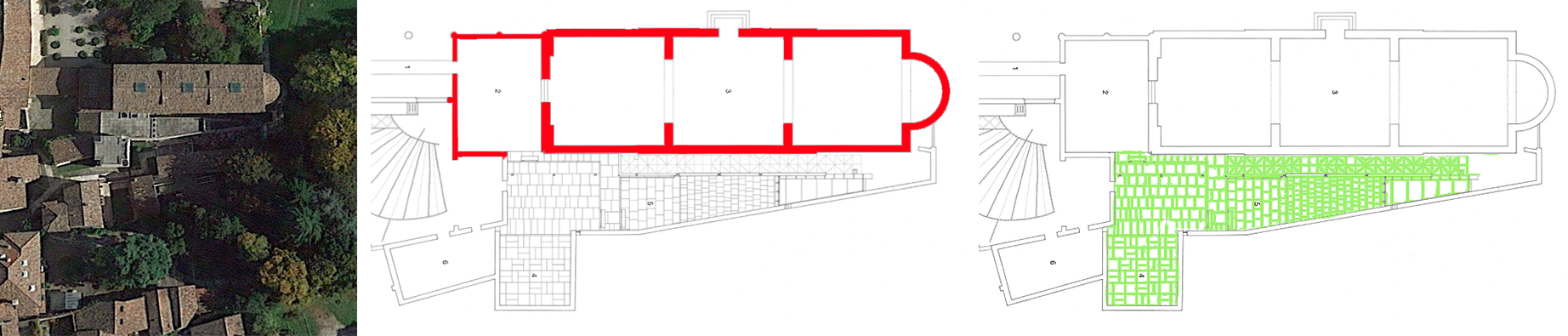

Carlo Scarpa Gipsoteca in Possagno, Italy. North of Venice, Italy, in San Vito d’Altivole, lies the cemetery of the Brion Vega family—the magnum opus of Venetian architect Carlo Scarpa (1906-1978). Nearby, in the village of Possagno, is another of the architect’s projects. Modest in scale, his addition to the existing Gipsoteca Canova, familiarly called the Museo Canoviano, forms an ensemble dedicated to the plaster sculptures of Italian artist Antonio Canova (1757-1822)—the name Gipsoteca meaning collection of plasters in Greek.

Museo Canoviano

Like many of Scarpa’s interventions in historic places, the pavilion-like extension to the existing 19th century Neoclassical museum is both humble and majestic. Humble in the architect’s respect for the historic fabric, and majestic in establishing a contemporary dialogue between the old and the new. As a young student, I only knew about the project through books and faculty praise, however my first visit was already more of a pilgrimage than an excursion to check off a building on the list of Scarpa’s projects. My trip to the Gipsoteca left me with indelible memories: the setting of Canova’s sculptures within an architecture of light endowed the addition with a sense of ethereal space.

In Scarpa’s characteristic manner—discovered through visits to other sites, I understood that one cannot dissociate his museum architecture from the exhibited artwork and vice versa. In fact, Scarpa’s foresight in developing a modern museography was to choreograph the display of art with the architecture. In the Gipsoteca, this duality between Canova’s artifacts and an architecture at the service of the displayed art was paramount.

My in situ experience became an internal conversation about process, creativity, and architecture’s higher purpose. This played a role in my personal resolve and contempt for self-referential architecture (need I say an architecture of objecthood) that has been legitimized in both academia and the public realm over the past decades.

Upon the death of their “favorite son,” Canova, the town of Possagno decided to erect a basilica-type gallery adjacent to the artist’s birth house in order to preserve his work. Marble statues, original plaster casts, preparatory wax and terracotta sketch models, marble slabs, and other artifacts (working tools, diaries, and personal mementos) were retrieved from his studio in Rome and added to artefacts in Possagno to form the nucleus of the museum’s collection.

According to Giulio Carlo Argan, art historian, former mayor of the city of Rome, and author of one of the most important essays on type and typology, Canova was considered the most celebrated neo-classical sculptor of his time, thus the desire to dedicate a museum to his oeuvre.

Canova’s father was a stonecutter, however, from a young age, he was raised by his paternal grandfather who was a stonemason. This upbringing paved the way for Canova’s artistic motivation through the excitement of cutting, shaping, and creating wonders out of stone that would compete—in his words—with the most beautiful classical statues.

The marble figures exhibited at the Gipsoteca are nothing less than superb; they translate Canova’s genius and technical authority at full scale, and illustrate the nuance and subtlety of human modulation. It is interesting to note that many of the plaster and terracotta cast models contain bronze nails distributed on a gridded pattern, so that with a sophisticated mechanism called pantograph, Canova and his apprentices could replicate the exact measurements from plaster casts to marble stone (above images).

The history of Scarpa’s addition (1955-1957) to the Gipsoteco/Museo Canoviano is well documented, both in terms of the history of the project and the descriptions of the exquisite, and often subtle architectural features found throughout the new building (i.e., the consideration of the addition as “Scarpa’s interpretation of the traditional walled patio garden as an exterior space,” thus the suggestion of an interior pavement treated similarly to patio pavers.) (Image above in green).

Yet, essay after essay devotes particular attention to Scarpa’s mastery which offers the museum’s space “… more abstract qualities of atmosphere and light.” Contrary to the original museum/basilica’s coffered vaults—with central lightwells illuminating the art work—Scarpa created two matching corner skylight windows that allowed light to bathe the surface of the interior plaster walls and, as he states “…to cut, if possible, the blue of the sky.”

This engages Canova’s artifacts within an architecture of light and shadow, a sensitivity that sets the Gipsoteca (and many other of Scarpa’s interventions) apart from conventional approaches to museum designs current at that time. Of note, I found a number of paintings that, at least for me, hinted on Scarpa curiosity towards the window in a pictorial space (Image 3, and 4, above)

Despite this focus on light, and while viewing the space in utter amazement, my eyes were drawn to a particular spatial moment. I was intrigued by the transition between existing and new buildings; an architectural moment found in many of Scarpa’s other works (Olivetti Showroom in Venice (1957-1958), Galleria Fondazione Querini Stampalia in Venice (1961-63), and Museo Civico di Castelvecchio in Verona (1959-1973)). Scarpa’s predilection to mediate between the new and the old—and not the present versus the past—enables the architect to showcase his artistic and aesthetic ideas by establishing a complicity within a preexisting historical context. These ideas are typically developed through a series of tectonic moves expressed through a material and/or spatial joint between the existing building and the new intervention.

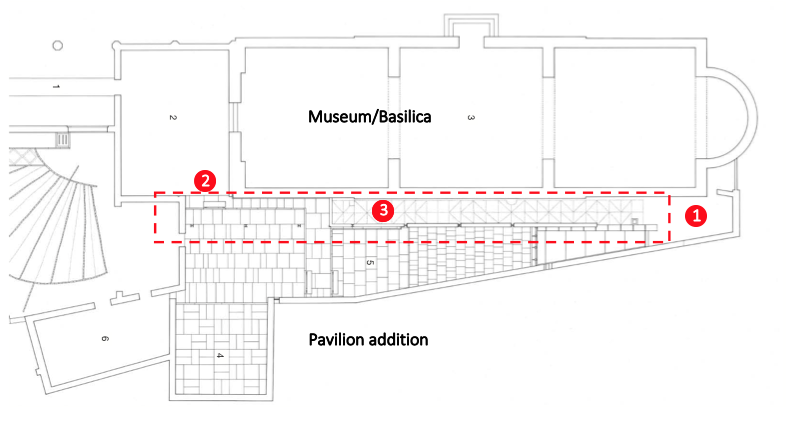

In the Gipsoteca project, Scarpa treats the addition as a separate L-shaped building in which the tall stem of the L parallels the existing thick-walled Basilica containing three main exhibition spaces (above image). Here the idea of the joint is given two distinct treatments. While it defines itself as a continuous visual wedge between the pavilion and the existing museum (image above in dashed lines 1), the joint differentiates itself as being both an entrance physically linking the interconnecting new gallery spaces with the Basilica’s foyer (above image 2), and provides an elongated open air space that gives physical distance between the addition and the existing building (above image 3).

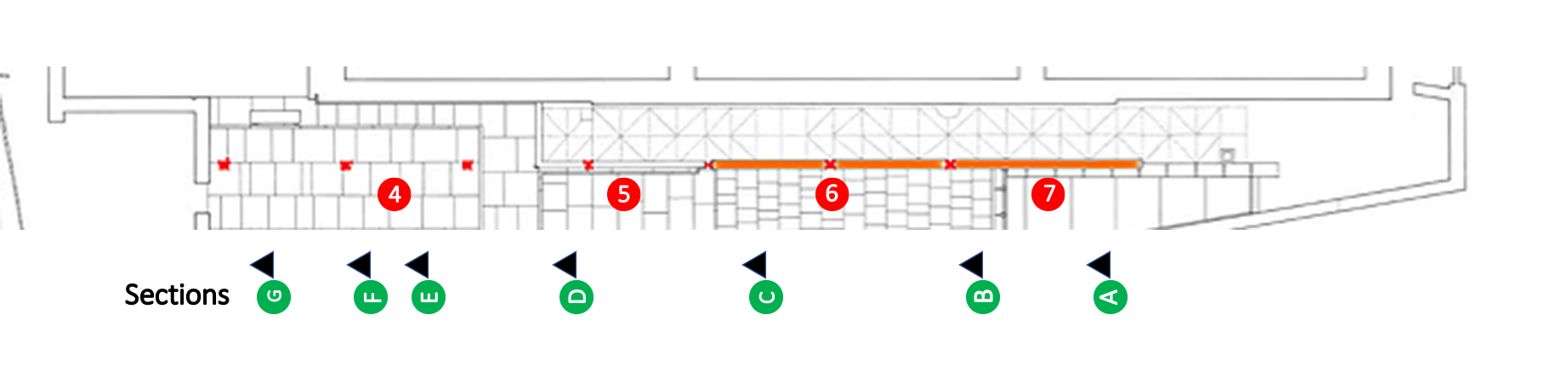

These two spatial subtleties (2 and 3) are achieved primarily through the creation of the treatment of the inner edge of the joint that resembles an arcade. Defined by seven metal columns (above image in red) of which three at the entrance are free-standing (4), they are followed by a fourth column that assists in articulating the glass separation between inside and outside (5), to finally lead to the three remaining columns (6) that merge with a screen-like wall (in orange (7)) that reveals and conceals intermittently the wall of the existing museum through a series of small apertures in the wall.

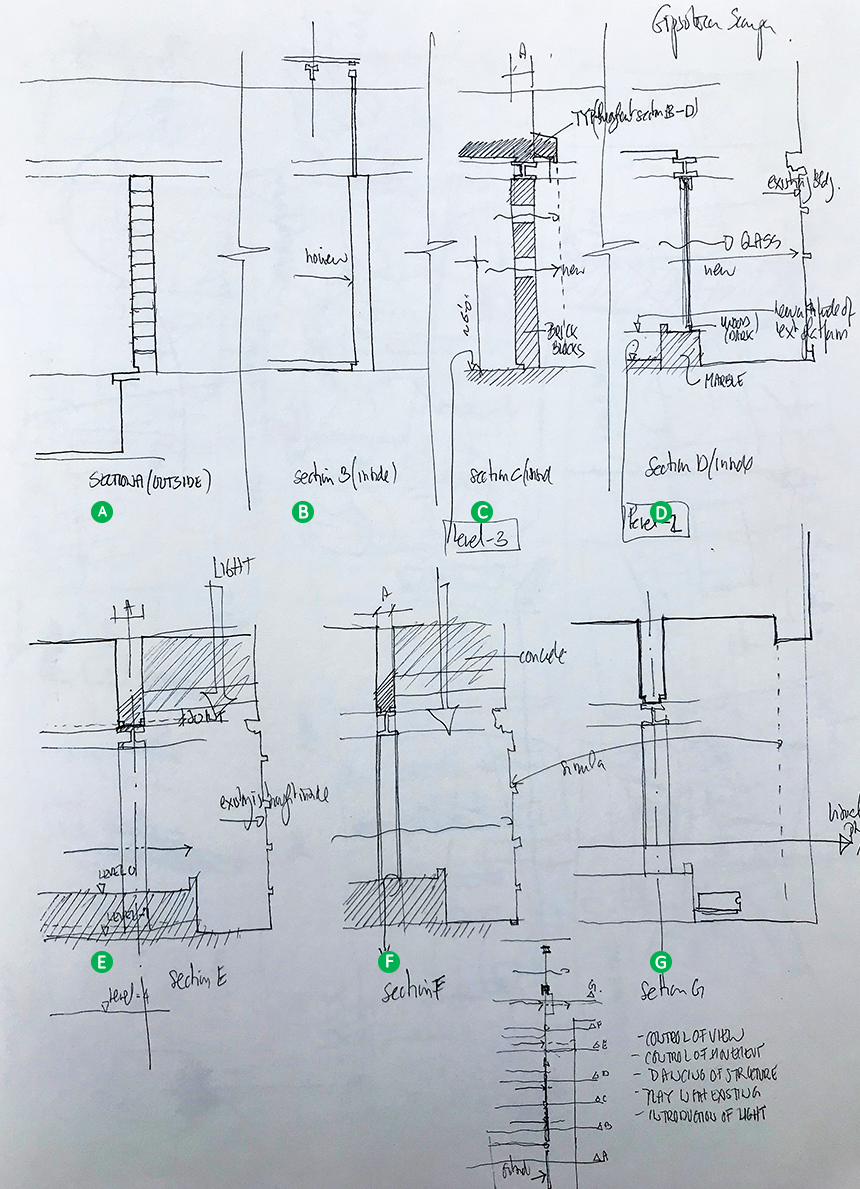

While the plan of the arcade appears straightforward, the magnificence of Scarpa’s spatial intentions at this particular moment is revealed in section. The following seven sectional sketches (above and below image A through G (in green)) record these basic principles and reinforce my belief that the emptiness of the joint is not the most important element, it is how Scarpa treats the edges of the joint that is his genius.

Sketch by Henri T. de Hahn. Note: column in section E rotates by 90 degree in section F, to rotate again in section G by 90 degrees.

Additional blogs on the work of Carlo Scarpa

Carlo Scarpa Venice entrance pavilion

Carlo Scarpa and detailing

Carlo Scarpa’s Gipsoteca in Possagno. Italy

Carlo Scarpa’s Gavina Showroom in Bologna, Italy. Part 1

Carlo Scarpa’s Gavina Showroom in Bologan, Italy. Part 2

Galleries of other works by Carlo Scarpa

Carlo Scarpa, Cemetery Brion Vega

Carlo Scarpa, Castelvecchio

Carlo Scarpa, Giardini

Carlo Scarpa, Gipsoteca

Carlo Scarpa, IAUV Architecture

Carlo Scarpa, Querini Stampalia

Carlo Scarpa, Olivetti Showroom

Carlo Scarpa, Banca Popolare

Carlo Scarpa, Venezuela Pavilion

All unattributed images are from Google public domain