The importance of sketching

To design a project, Part 2. I have always liked to draw and more importantly, sketch conceptually. I was trained to think visually, and for me there is no better way to convey ideas than by drawing; from conceptual thinking to plan development.

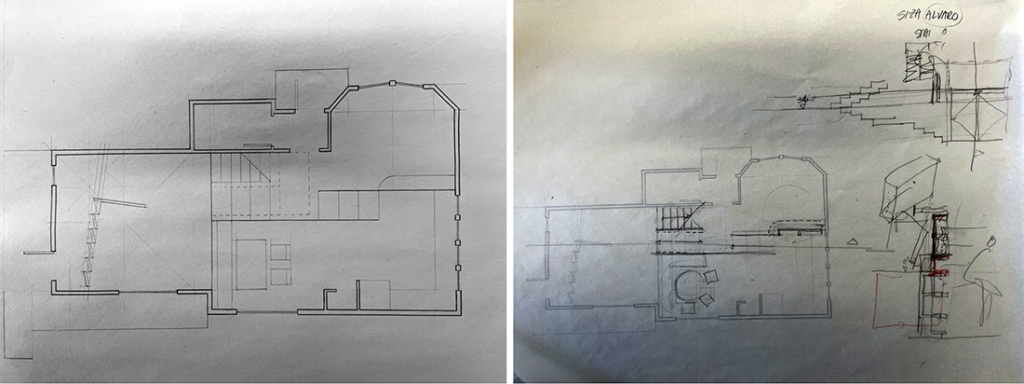

For students—at least those I have mentored over past decades—observing first-hand how I think and develop a project through sketching instills confidence. Certainly, with experience, sketching becomes second nature, and using various lead or color pencils (typically of a softer lead), I can articulate ideas with the student and help them grow in their own understanding of the design process.

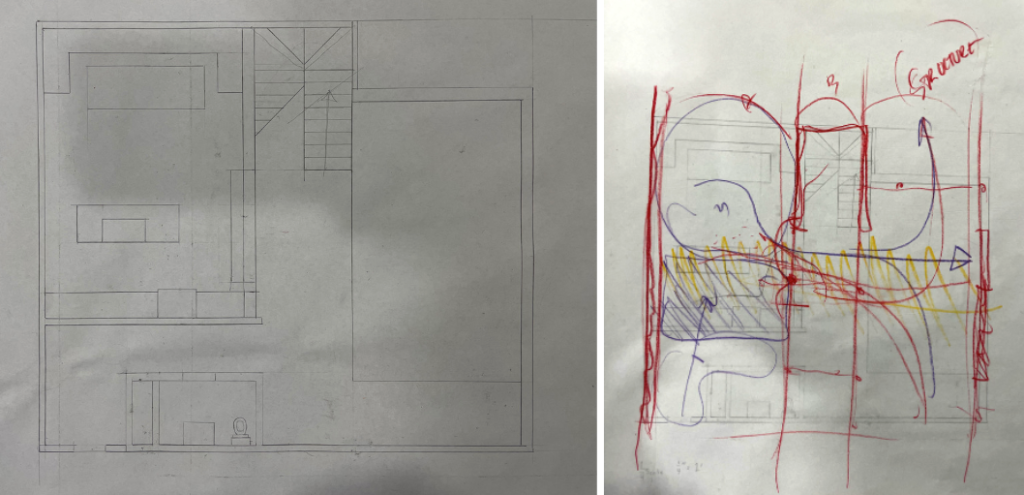

This is critical to clarify ideas for both author and viewer. For the students, this visual and intellectual activity of seeing first-hand how faculty discuss a project incorporates how unforeseen strategies emerge through the act of sketching. For me, it is a important means of partaking in the students’ way of thinking. In this process of sketching with students, I recognize that there are obvious downsides (i.e., questions of form; concept versus the form of a building; and authorship of the sketch).

At the end of the day, I appreciate how the students’ motivation, energy, and confidence is built up after each desk crit. To see (or even better, to observe), to process information, and understand how a faculty or peer interpret their project, is to open multiple paths of investigation for the student through an understanding of how to design a project, which is different than the simple act of doing a project.

Offering suggestions in the hope that students find solutions on their own seems a great Socratic approach, but there is a balance between suggestion and sitting down with a student, taking a pencil, and sketching with them about how a project can progress.

This may seem self evident, but in an environment that emphasizes John Dewey’s learn-by-doing approach, learning by example seems critical, and this more than ever in an Instagram culture where a thoughtful understanding of how things are made, may well be a thing of the past. Sketching and discussing with students has proven, at least for me, an invaluable strategy in seeing projects progress to a next level of excellence for the students.

What does sketching entitle?

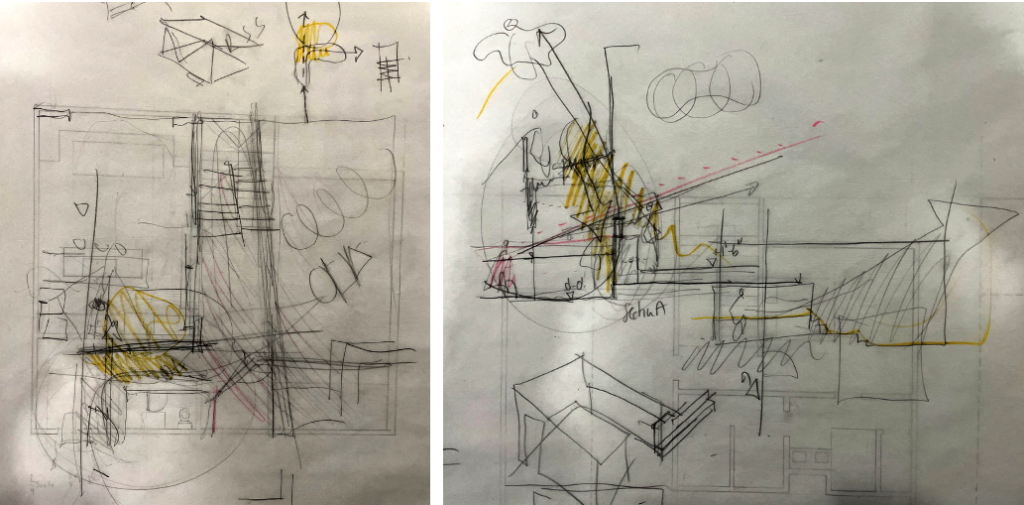

Helping students think about how to design a project is fundamentally different from showing them what to do in a project. When sketching with a student, I invite them to understand how space in perceived, how a procession is established from room to room, room to space, or space to space. This exploration of movement should come naturally as they define limits, edges, and transitions between spaces and rooms. To bring contrast to the sequencing of a horizontal promenade architecturale, is to add vertical circulation and a healthy dose of re-thinking function and program in an innovative manner. Then you are on your way towards something truly rewarding.

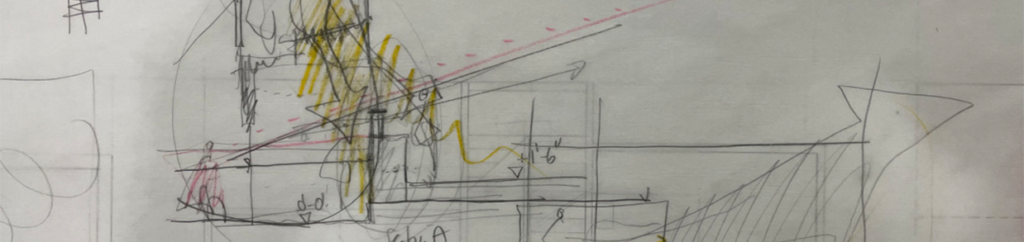

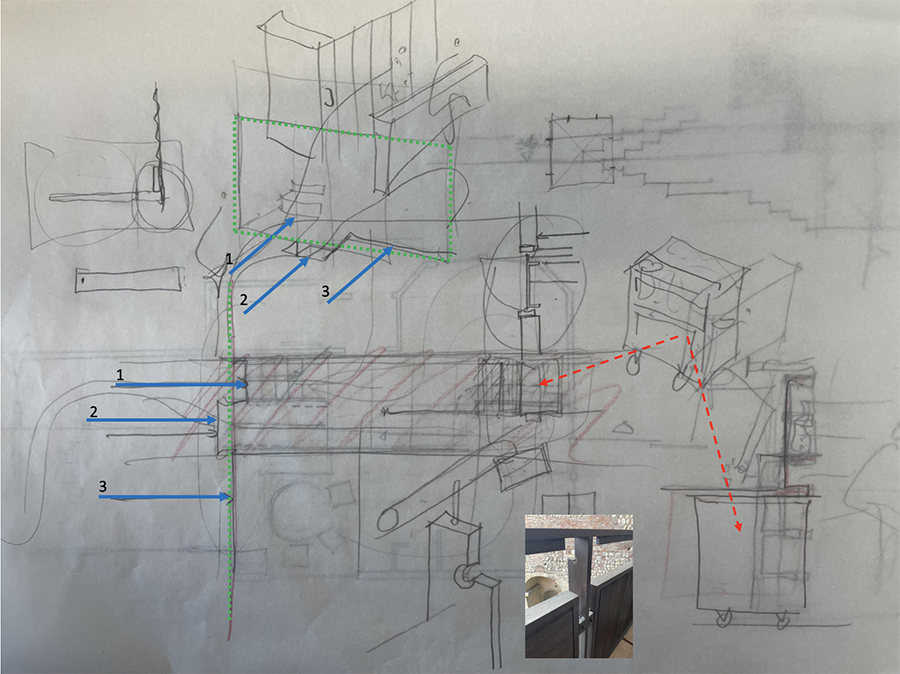

Similar to the sketch in Image 2, here work is conducted in defining an entrance way, given the tenuous L entrance. View towards the kitchen and light from the above terrace assists in giving the entrance a processional quality from front door to hallway in front of the stair, from which the living room and kitchen flow from there.

Empathy towards this process is to believe that design sets the human experience center stage at the beginning step of an architectural process. Certainly, this does not jeopardize the adage of the primacy surrounding the discipline of architecture. On the contrary, the balance between haptic experience and the legacy of architecture as history and theory is when the design process takes its full value. Disciplinary precedence and its typological memory constitute the act of creating. And it is here that I return to my previous trilogy of:

- The project per se;

- The inclusion of history and theory as precedence to the project, and most importantly;

- The process or theory of how to design a project.

All three aspects merge into the underlying material architects work with when designing a project. It is part of the conceptual variants that can be re-formalized, set in form, and translated in various ways according to the contemporaneity of one’s times. The student’s role is to order these points in a conscious and articulated manner. In short, this is about the theory of how to design a project.

Students learn how to develop a parti (spatial organization of function) based on an architecturale promenade. Its spatial continuum is defined by movement, even if a procession includes built-in disruptions to emphasize a series of events along the path of spatial discovery. To achieve excellence in sketching as a process, is to set oneself in the space created and to move through it in a cinematographic way. While drawings convey space—or the outer edges of space—students need to initially learn, practice, and rely on basic systems of codification.

In this process, there is the important role that intuition plays, the dialogue between oneself and the project. Project and author have a back-and-forth conversation, and while there is always the need to claim that ‘I wanted to,’ perhaps the best strategy is for the project to inform its author about the nature of being. Capturing possibilities is at the end one of the most creative activities while sketching and I hope that my students will be well versed in this way of thinking.

Conclusion

Students slowly learn a process or theory of how to design a project. It is far from easy, but I have already witnessed great strides in their abilities to express ideas, calibrate their spaces, and bring coherence and spatial complexity to their projects. Perhaps the following thoughts can add to a never-ending discussion:

- Process should never be a behind-the-scenes activity. It must be integral to the visual and intellectual decision making of any project.

- Process is about the deepening of knowledge and often the creation of new knowledge.

- Process, if done correctly, becomes a record of an emerging thematic coherence with its strength and opportunity, documenting the taken and dismissed paths.