To design a project. Part 1. When teaching—at least where I stand today in my academic career—I think of countless blogs that I should write about architectural education. This is particularly true given that year after year, I see students struggle with similar topics.

The primary purpose of my blogs is to further student education outside the design studio. Today’s generation of students are an Instagram culture. Thus, to add value to their education, I have found it important to promote knowledge that can be acquired and accessed outside the classroom, individually, asynchronously, and spatially around the world.

The richness of blog content

In order to address many student conundrums, my blogs tackle their apprehensions about design issues at various stages of the design process. To me as a faculty, there is an inferred understanding that to work on a project is to develop an approach based on three main points:

- The project per se;

- The inclusion of history and theory as precedence to the project, and, most importantly;

- The process or theory of how to design a project.

Rereading past blogs that touched on these three points, I realize that attention given to the theory of how to design a project (point three) was never fully explored beyond the importance of contextualizing history and theory as a design impetus (point two). In today’s blog, I will focus on point three, the part of design that is encountered by students but often never fully developed, namely how to design a project. As most of my blogs derive from my students needs, the below thoughts were triggered by current student work and the overall difficulty they have in advancing their designs with playfulness, determination, and, above all, creative confidence.

A student’s initial design gesture

I believe that for an architecture process to take place, there needs to be a beginning; something that allows a process. Let’s call this beginning having an idea (a program, a thesis, a position, or an argument about space) that establishes the designer’s initial aspiration from which their curiosity will unfold. From the challenge of translation of ideas into space—understood as a first attempt to give ideas visual presence in the form of a sketch (i.e., artifact)—I believe that transforming thoughts always comes with a number of obvious pitfalls. Let me highlight three that I encounter repeatedly.

First

Over the years I have seen countless iterations of basic shapes (platonic and geometrical figures). These formal manifestations result from a desire to make a gesture—something strong and unique—rather than to understand that the best architectural form is where geometry and meaning work in tandem. Form without content is geometry (often associated with garrulous formalism, which is now furthered by digital bravado).

On the other hand, geometry with meaning is form—at least for me when I create architectural spaces. Yet, for a second-year student starting a design process this distinction is not necessarily understood. It is important they learn this from the outset, as it is a key driver for a successful project. I have made this mistake, playing with geometry without content, others have done it, and countless others will do it!

Second

The second trap in a design foray is when geometry becomes a precise configuration for a building. Students often confuse architecture with its image; a representation that is immediate and more easily consumable. This is particularly true in a digital world where images are finely curated to look good at first glance. We forget how much work has gone into these beautiful images, which remain images!

To consider geometry as building fails to respond to larger architectural issues regarding function, without even mentioning structure and site, or the intangible poetic forces of any project, which I call program. Again, geometry = building may be enough for students, it remains the responsibility of faculty to engage in a didactic way with students to enable them to think about the meaning of an iterative process.

Third

The third and final catch in a student’s approach is not of their making. In most architecture programs in the United States, one no longer teaches architectural fundamentals, at least what was once the bastion of excellence of any first-year program. The obsessive focus is on the education of an architect, regrettably often at the expense of engaging students with architecture and within the disciple of architecture through an interdisciplinary approach that takes its own life as it enters a physical realm.

These three challenges (shape, building, pedagogy), create for many freshmen an insurmountable obstacle. Students learn that geometry is a sign of their creative talent. Countless objects—forms on which any esoteric, or at best, tectonic meaning can be assigned—are produced throughout their first year.

Some are done innovatively, while others are perpetually stuck in past practices as if time never advanced. Projects rarely exhibit internal spatial qualities that carry basic architectural meaning. This faculty fixation does not help students move to second year; particularly when students are confronted with their first architecture assignment.

A critique of the status quo

Although shared by many colleagues, my observations remain personal and come from decades of teaching. Increasingly, I see fewer and fewer first-year design fundamentals transformed into robust architecture thinking for sophomore students. All of this traditional first year teaching—and not learning—is the result of many first-year faculty predilections to a Michael’s Arts and Crafts immersion. Immutable laws regarding principles of design legitimately promote notions of balance, contrast, emphasis, pattern, unity, movement, and rhythm, but do not contribute to what architecture is about: SPACE, and the thoughtful translation of ideas into space.

Many instructors cite the Bauhaus tradition (innovative in its time) to legitimize current pedagogical principles. I always wonder what principles Albers, Gropius, Kandinsky, Klee and other faculty at the Bauhaus would have used to establish a 21st century pedagogy. I am convinced that they would be of “this” time, and would have once again “killed” their masters through innovative pedagogical strategies; a metaphor that Raphael Moneo, Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate (1992), once shared when I was a student, regarding the danger of blind allegiance to any past or living master.

Of course, this is not to say all faculty follow this approach. Luckily where I currently teach, a recent hire has questioned the status-quo of first year by returning, in an innovative way, to a spatial understanding of tectonics. This is done by creating a number of project briefs whose results are provocative, architecturally driven, and which I am sure will better prepare students for their sophomore year.

Let us return to the aforementioned pitfalls

In order to address student difficulties, it is essential to focus first and foremost on their design during individual or collective critiques. This seems obvious for any design studio, and for faculty, it remains an opportunity to understand the project’s potential. More revealing is to witness the student’s timidity—or inability—to confront obvious impasses that seem insurmountable to them. Simply stated, students often seem at a loss when wanting to advance their project. They either stare hopelessly in front of their drawings or wait tacitly for faculty input. They don’t yet understand the richness of building on a theory of how to design a project.

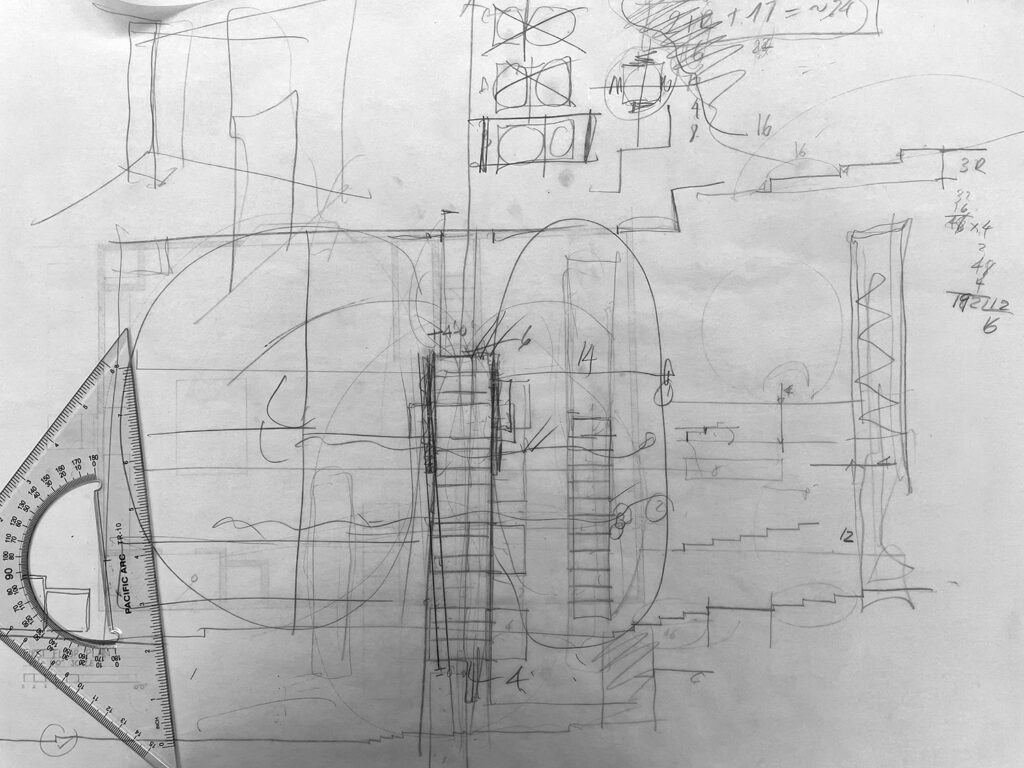

In this context, I believe that one of the most powerful ways to help a student overcome their lack of confidence is to sit and sketch with them. Sketching comes through listening to their speech intonations, hesitations, and silences, all the while seeing what they point to in their drawings. This ‘paying attention’ requires that faculty decipher through the students’ drawings what has been translated from ideas to words and drawings into perhaps, most importantly, the potential values of their design.

Students often do not see or realize the next steps, steps that can help their designs move towards the necessary excellence. This is a major role of a faculty, not simply conveying knowledge but triggering new knowledge that students can then bring to the table.