An architecture project. The education of an architect is primarily centered around a design studio with an architecture program describing the nature of a design proposition. This prompt, which is also called a brief, is usually open ended and offers basic directives on the nature of the problem to solve. The overall freedom offered by briefs, allows students to design a project by incorporating thoughts pulled from sources within and from outside of architecture.

An architecture project

Project descriptions may involve a list of specific and complex functional requirements associated with an urban site, including existing buildings and square footage. This kind of prompt is typically given to senior students as a required comprehensive design studio that is like a teaser in preparation for their three-year Architectural Experience Program (previously called internship) prior to becoming a registered architect.

Regardless of the nature of the prompt, students learn various methodologies, techniques and tools to carry out specific tasks during the design process. For me, this should always be accompanied by the setting in place of a thesis (big idea) which, unfolding through iterative conceptual sketches, flushes out their argument to get to the essence of the solution. The ‘end product’ is often orthographic or digital drawings, and depending on the student’s skill level, video walkthroughs that showcase the spatial relationships based on program, and their interpretation of functions, and the value of use.

In this process of simulating the real world, site conditions are a necessary component of the brief, as buildings engage a physical and cultural context. Also included, and dependent on the studio level, are codes, structural considerations, construction, and details which showcase the student’s ability and understanding of how buildings come together. This process, from concept to execution, is accompanied by desk critiques and more formal presentations with occasional guest reviewers at key milestones during the semester.

Of course, there are as many teaching methodologies as there are faculty, a mix broadened with the innovative pedagogical strategies showcasing junior faculty’s contemporary interests. However, if the project remains the locus for students to learn to design, I remember at my alma mater, the EPFL, two additional complementary dimensions that were integral to the project within the design studio. Specifically, the theory of the project and the theory of the act of projecting.

Theory of the project

I believe that only rarely do we work within a cultural vacuum to create something meaningful. There is usually a lineage of ideas, visual traditions to be questioned, and important societal implications that allow architecture to either reflect epochal changes (in German represented by the untranslatable words Zeitgeist and Weltanschauung), or establish where society may advance through the filtering of ideas (i.e., the art movement Cubism influential in defining a new architecture of the early 20th century).

This stand assumes that we are not alone in the act of creating, and suggests, at least for me, that projects worthy of interest are those that re-invent rather than invent, thus the need for precedence to contextualize any design vision. What I mean by that is that there is a need to legitimize ideas by confronting them with a larger body of our discipline, namely within the history and theory of architecture. This is a tricky proposition when deciding how to proceed in selecting, choosing and incorporating external ideas for the development of a project. This process of reinvention remains a recurring and honest question that starts from our early student years throughout our lives as seasoned architects and educators.

Architects who wish to avoid the conundrum of using examples as a point of precedence endorse the idea of the autonomy of the discipline of architecture—where grammar, syntax, and vocabulary tend to be specific to the design process (i.e., Peter Eisenman). Yet, given my interest in working within an existing context, and developing the meaning of a project by re-inventing the existing, I always reflect on what the history and theory of architecture has offered me. Not simply to reassure myself that I am part of something larger, but to acknowledge that there are elements of permanence in architecture that need constant re-evaluation; never forgetting that the human being remains the most essential component in the design of architecture.

This relationship to precedence allows us as educators and architects to expand on fundamental principles as defined in architecture treatises (i.e., the classical concepts of axis, symmetry, order, hierarchy, rhythm, balance and contrast to name but a few). With this perspective, fundamentals can now be seen within a dynamic context, promoting a necessary evolutionary attitude in the art of making; one that no longer accepts fundamentals as immutable facts to legitimize tradition.

The incorporation of new ideas can be subtle (nature of being) and sincere (being influenced), or brash and without any serious thought about appropriating, borrowing, copying, lifting, or even plagiarizing the past. The latter has always been a concern in academia especially when reviewing term papers. More recently, plagiarism has surfaced as a topic within design studios.

In a world that offers everything at one’s fingertips through the use of a smart phone, students may fail to understand the lack of an ethical stand toward the integrity of their project. Thus, architecture programs run the risk of having students lose their belief that a design project represented the pride and expression of their personal ideas, regardless of how idiosyncratic they are. Fortunately, these incidents are rare but, still, they are concerning.

Referencing the past is key to what I call theory of the project. It is a way to have students discover affinities with precedence by which to confront their design process, or simply get inspired to push their ideas further. To appreciate past projects is one thing, but to focus on specific architectural topics is another. Thus, and beyond pointing to specific architects, movements, or ideas, I like to focus on issues that not only help a particular student, but become a moment of collective learning among the class cohort. Often, these impromptu moments are generated by questions and struggles the students express about their projects.

For example, when teaching, I advocate that for an architecture project to be successful, understanding basic structural static principles goes beyond how loads affect the structural integrity of a building. Structure, as a way to define spatial conditions, becomes an extraordinary tool for students to give meaning to the experience of space and place.

To this point, I often reference projects with an emphasis on how architects have created space by thinking of structure historically within their contemporary interpretations; in particular as an evolutionary principle that brings space to pure poetry. While one-on-one discussions between students and faculty are important, I have written three blogs intended for a larger cohort of students to learn about structure. I consider them as part of a number of discussions on the theory of the project that accompany the studio prompt:

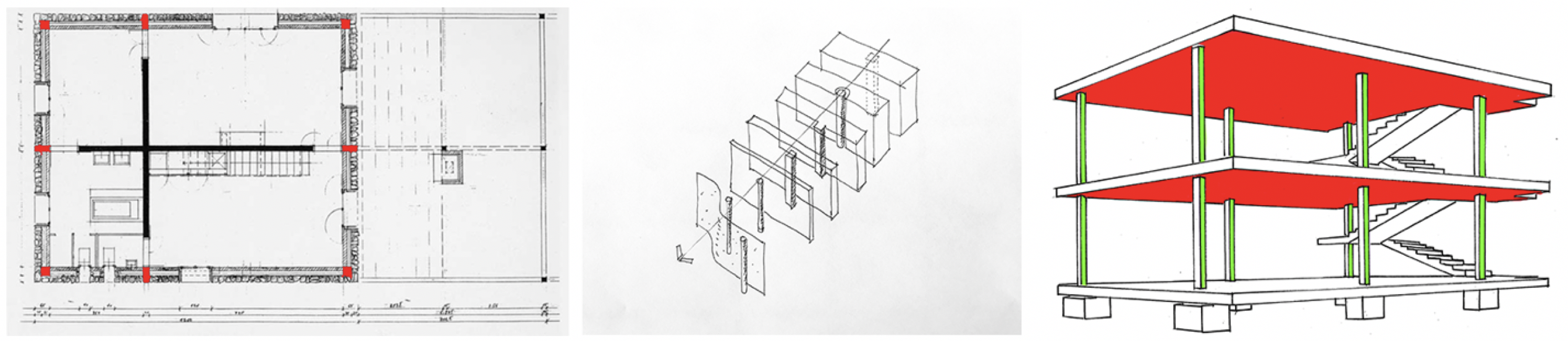

Image 1: Structural principles at the Tavole House by Herzog et de Meuron (left), historical evolution of wall and column (middle), element, system and structure in Le Corbusier’s Dom-Ino House concept.

Image 1: Structural principles at the Tavole House by Herzog et de Meuron (left), historical evolution of wall and column (middle), element, system and structure in Le Corbusier’s Dom-Ino House concept.

- Herzog et de Meuron’s project The Tavole House, which incorporates an historical evolution of the wall and column. The blog presents this house as a semantic interpretation of structure.

https://atelierdehahn.com/architectural-education-herzog-et-de-meurons-tavole-house/ - Louis I. Kahn mentions that one of the greatest moments in architecture was when the column departed from the wall. The blog analyzes four projects specific to how this allegorical statement is brought to life in his buildings.

https://atelierdehahn.com/architectural-education-kahn-poetry-wall-column/ - The blog contributes to understanding structure as both an element and a system defining space.

https://atelierdehahn.com/architectural-education-element-system-structure/

The meaning of theory of the act of projecting

While students work on their project by incorporating precedence (theory of the project), there is one last aspect that is critical for them to advance the project: namely the act of projecting. Why is this concept important and how does it assist students?

1. i.e., sketching, diagramming, conceptualizing

During individual desk critiques, discussions typically focus on the progress of the student’s work. Understanding their process, and how they make decisions and incorporate more complex ideas is often the topic. However, words of wisdom and encouragement should always be accompanied by discussions on the act of projecting. What I mean is that without specific guidance in the manner of how to develop their project, students are often left with high aspirations, yet few tangible ways to advance their ideas.

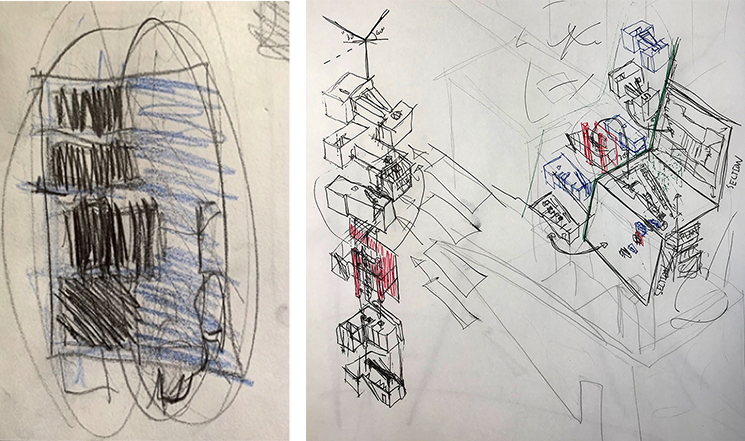

For example, when we encourage students to sketch, few—as least in their sophomore year—are able to choose between drawing, diagraming, or conceptualizing their ideas. Each of these endeavors carries meaning and is chosen for particular reasons during the process of exploration. I see that too often students re-draw their plan or section, missing the opportunity to abstract the design, or more importantly, the idea that lie behind the intention of their design.

Either endeavor in the design process is often conducted timidly as the students fail to understand the question at stake. To provide guidance on which sketching technique to use is critical for the project to advance (achieving a beautiful drawing is a bonus, but not the intention). Even the choice of use of a thin pencil versus a thick graphite pencil; the introduction of color to highlight specific intentions; and, most importantly, the decision to draw rapidly and succinctly remain challenges that are important to address.

When a student feels more at ease with sketching, I regret that most of these drawings are not followed by processes of iteration. Often a single sketch is produced, with no follow up on variations of the ideas. I advocate two important iterative methods, both important, yet different techniques useful for specific endeavors while seeking clarification for the overall project.

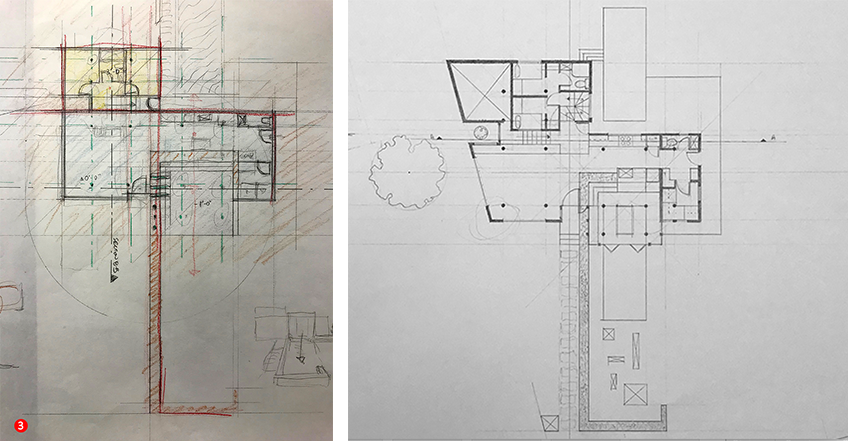

Finally, while it is important to sketch ideas and engage a visual dialogue between intention and actual produced image, students will rapidly face the question of how to move from a sketch to a drafted sketch, from a drafted sketch to a drafted drawing. All of these milestones in the project, reflect the importance of the act of projecting.

Image 2: two students: conceptual diagram and conceptual drawing for the design of an exploded axonometric

Image 2: two students: conceptual diagram and conceptual drawing for the design of an exploded axonometric

Image 3: Student sketch-draft and drafted sketch (middle right and right)

Image 3: Student sketch-draft and drafted sketch (middle right and right)

Similar to the theory of the project, the following three blogs were created for students to learn about the above topics and are part of the act of projecting that accompany the studio project:

- https://atelierdehahn.com/architectural-education-about-conceptual-diagraming/

- https://atelierdehahn.com/architectural-education-sketching-iterative-process-2/

- https://atelierdehahn.com/architecture-education-study-sketch-drafting-part-1/

2. i.e., model making techniques

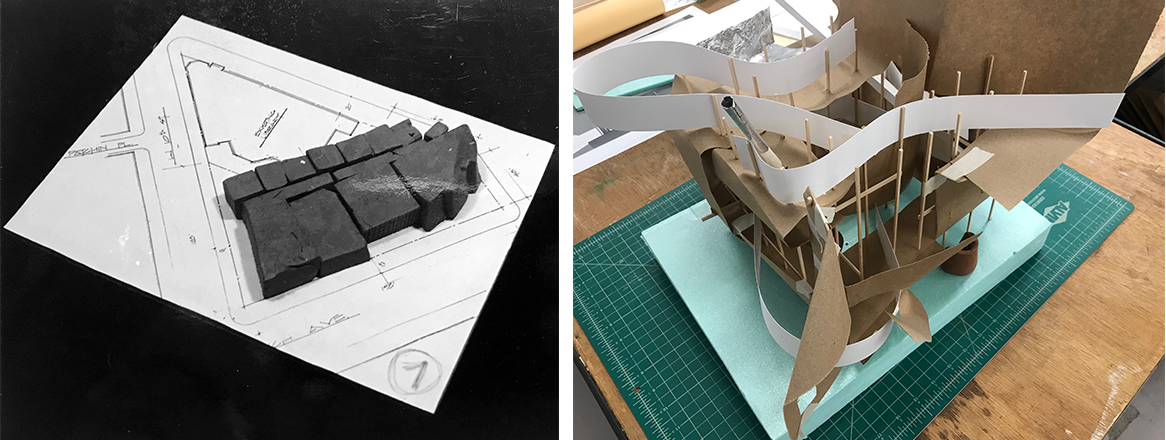

If drawing, sketching, and conceptualizing are integral to the visualization of a student project, exploring a project three-dimensionally (in model) is equally important to the progress of the project. In particular, exploring model-making techniques cannot be simply left at the whim of the student’s talent, but should be accompanied by examples that give guidance and don’t leave the student in the dark. I understand that this is a pedagogical stand, one that accompanies the students rather than having them experiment at every moment of their design.

Learning a process has value in the act of projecting, and offers some fundamental and basic guidance in how to approach a first foray in model building—not as an aesthetic pursuit, but one where conceptual design thinking accompanies hand gestures through appropriate or unconventional usage of materials. Again, these techniques are to be understood as methods of investigation for specific moments in the design process.

Image 4: author’s sketch mass model made out of plasticine (left), student sketch model out of various materials (right)

Image 4: author’s sketch mass model made out of plasticine (left), student sketch model out of various materials (right)

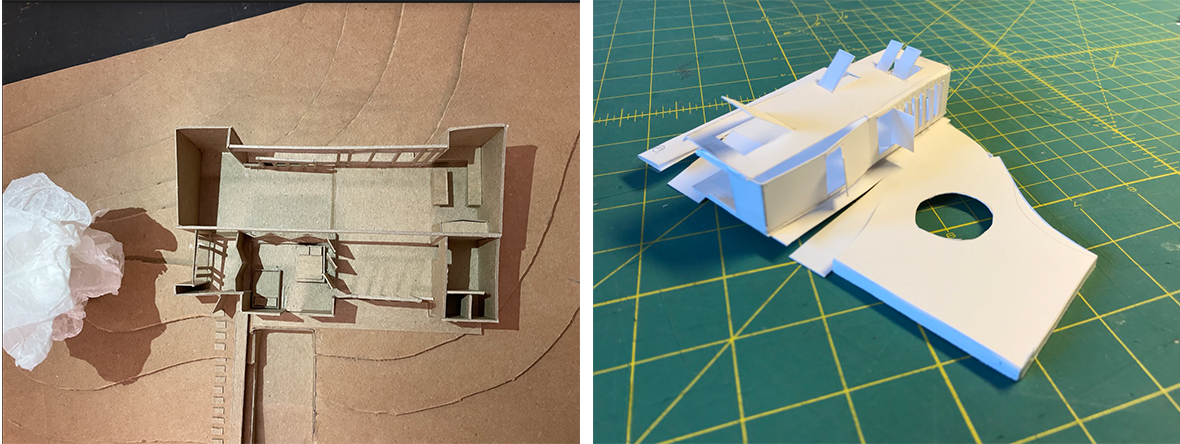

Image 5: student cardboard/chipboard model with site (left), author’s sketch model by folding one single paper

Image 5: student cardboard/chipboard model with site (left), author’s sketch model by folding one single paper

These three blogs shed specific light on the above educational strategies:

- https://atelierdehahn.com/architectural-education-why-model-sketching-part-3/

- https://atelierdehahn.com/architectural-education-why-model-sketching-part-2/

- https://atelierdehahn.com/architecture-education-model-sketching/

Conclusion

While the project remains the locus to learn about designing architecture, I have, since my own tenure as a student, wished to accompany learning with key moments: techniques and tools that are both intuitive and rational for the sole purpose of giving some sense of comfort as students progress in becoming seasoned designers. This approach has always been eye opening for both my students and myself, especially in translating thoughts into actions.