Architecture thesis, Part 1. Most United States undergraduate architecture students will engage in a thesis project that spans the entirety of the last semester or academic year. After learning about the foundations of their discipline between their 1st and 2nd years, followed by the consolidation of ideas that takes place in their 3rd and 4th years, students are asked in their last year to demonstrate a sense of independence, generally through a more robust project called a thesis project.

The following content suggests a five-point approach to developing and completing an individual capstone endeavor. These points are both a summary of my own educational experiences as a thesis student, as well as my tenure as a teaching faculty member at various academic institutions.

This is not an exhaustive examination of all aspects of a thesis –there is far too much to cover and many well-researched books are available for an in-depth understanding of the nature of a thesis. These five points are offered as a guide to enable students to focus on the number of steps that will assist them in framing important questions leading to their thesis. Also, students will find a set of examples to compare and contrast the nature of a project versus that of a thesis. These are examples of thesis projects, not of thesis statements. An important difference.

A final introductory point, but certainly not a minor one, is that for the these to be successful it is essential that students follow their academic requirements and meet regularly with their faculty advisor(s) to discuss their interests and methods of achieving what is, perhaps, one of the most important projects of their early career!

“…What are the relationships between ideas and architecture? Can an authentic and meaningful architecture be developed in our current pluralistic context? Can successful aspects of Modernism remain vital in the context of Post-modern criticism? How can architecture help us to form an understanding of our cultural context? It is in a context of inquiry that discourse can best be carried out, a questioning before criticism, concerning ideas that establish the foundations of judgments and products in our civilization. Architecture forms a vital part of human culture, and thus we are concerned with the development of architectural ideas. By examining the relationships between architectural intentions and implementations, we may come to a more comprehensive understanding of meaning in architecture and architectural thought…”

ARCHITECTURE AND ABSTRACTION

Introduction to Pratt Journal of Architecture

“The cat sat on the mat is not a story.

The cat sat on the dog’s mat is a story.”

— adapted from John le Carré

Thesis:

Thesis:

A position or proposition that a person advances and offers to maintain by argument

- What is the BIG PICTURE/IDEA that is important for you to demonstrate/tackle over the time of one/two semesters? A thesis is not a project; it is the idea –an original idea– that brings about a project.

- Has this topic already been appropriately addressed and/or do you believe that you can add a different perspective or a different approach to this particular topic? If yes, can you frame your argument within those existing propositions?

- What new insights and critical thinking would you like to bring to your thesis?

- What is the difference between a thesis and an architectural thesis?

An architectural thesis distinguishes itself by having a particular tectonic expression linked to the specifics of an architectural vocabulary, leading to an argument about the configuration of space.

Examples:

A project: an addition and/or renovation of the college of architecture design studios by providing a state of the art learning environment.

An architectural thesis: addition of much needed studio spaces on the rooftops of all other academic colleges on the university campus because the sine qua non-condition of the education of an architect lies in its interdisciplinary within those units.

The following five points – argument, objective, problematic, methodology, and communication – are intended to be followed as a series of incremental steps, moving from the overarching BIG IDEA—meaning what do you intend to demonstrate—to a more in-depth methodology leading to the final visual and oral presentation of the thesis. While one may be tempted to start randomly with one of the points, it is important to first read each one carefully to understand the inherent order in which they have been formulated. Stated differently, the execution of the points occurs in order as one builds from the initial argument, through to the next point and the next. Following the points in order will assist in creating a comprehensive approach to a successful thesis project. And yet, depending on how a student approaches their thesis, all five points may be interchangeable in their order.

- Argument:

a coherent series of reasons, statements, or facts intended to support or establish a point of view.

- What do you want to prove, demonstrate, persuade through your thesis?

- What are the basic premises in developing your argument?

- What type of reasoning are you employing to define your argument?

- What are you curious about in stating your argument?

- Objective:

something toward which effort is directed: an aim, goal, or end of action

- What specifics do you wish to address and how do you strategically want to research/address them? Objectives are often considered as an action plan that get you from where you are to where you want, through a series of concrete steps?

- How will you describe the path of your argument and your thesis?

- What form does your objective take –text, diagrams, pathway, etc.

- What specifics do you wish to address and how do you want to research them with tangible strategic actions aimed at accomplishing those tasks that you set in place?

- Problematic:

Is the action of posing a problem

- What areas do you need to focus on in order to address the “emerging” problem(s) that accompanies your stated argument, objective, and thesis?

- What are the precedents that can influence your decision-making?

- While conducting your research, you may find the “true” topic of your argument, thus do not hesitate to adjust your initial premises

- At last, challenge yourself but do not get overwhelmed by what you find!

- Methodology:

the analysis of the principles or procedures of inquiry in a particular field

- Define a draft narrative and refine it during the entirety of your thesis to establish a framework of your investigation that explains your objective, problematic, and argument. This will lead to a proposal and should include a method of study based on the particularities of your investigation, accompanied by a solid bibliography and reference list

- Which methodology will you use to address your thesis? Inductive (probable/uncertain) or deductive (strong evidence) processes? Note that both may be used over the course of your investigation

- Do not avoid comparing and contrasting various methodologies that you experience during your studies, and be open –if necessary– to inventing your own methodology.

- Communication:

a process by which information is exchanged between individuals through a common system of symbols, signs, or behavior

- How do you want to communicate and share your findings at your oral defense?

- Should you support your thesis project through traditional systems of notations specific to the discipline of architecture, borrow methods of findings from other disciplines, or do you simply invent your own language, syntax, vocabulary, and grammar to exhibit your thesis?

- Will you feel comfortable not meeting your argument? This does not mean that you have not learned.

In conclusion, it is important to note differences between a project and a thesis. The following examples -based on questions of a learning environments, issues of domesticity, and the re-invention of a building type suggest possible differences:

Thesis examples

Example 1:

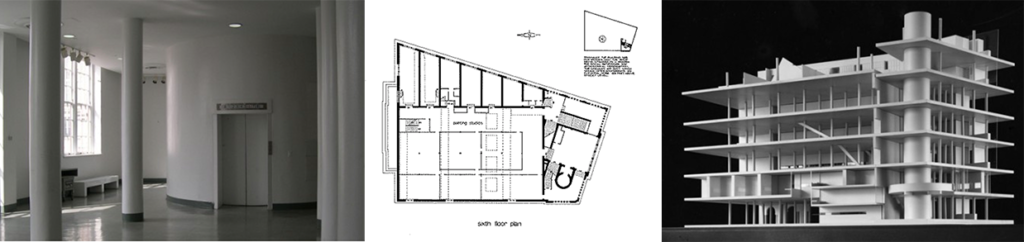

This example (designed and completed by John Hejduk architect, and Dean of The Cooper Union in NYC) focuses on the renovation of the foundation building at Cooper Union. As a project the design would simply offer appropriate and updated teaching and learning spaces to educate architects and artists.

Hejduk’s thesis for the building was to create a learning environment that was to be showcased within the spaces of the building. If a student had a particular question about an architectural topic, particular aspects of the building were designed to exhibit answers in how those questions were addressed and resolved. The building became an open book of architecture.

Example 2:

Commissioned to rethink a Kindergarten for the children of Como (Sant’Elia Kindergarten), Italian rationalist architect Giuseppe Terragni avoided developing a project of educational spaces that reflected 19th century values.

On the contrary, he developed a thesis that recognized and promoted new pedagogical aspirations and transformed the entire program to vibrant and complex learning opportunities that partook in a new architectural language –creating quality classrooms filled with light and immediate extensions to the outside; a Mensa for children to get a school lunch and dedicated spaces for bathing activities –the later two as a model of life that extended and complemented family life as integral to the health and welfare of its future citizens.

Example 3:

This example is about a thesis regarding domesticity. In it, French architect Jose Oubrerie creates the Miller house in Lexington, KY, wherein he establishes a model of life showcasing his vision of how parents may interact with their adult children.

Contrary to developing a house which contained the necessary programmatic spaces, the architect formulated a thesis that the house was a home within a city; where each child and the parents separately inhabit a vertical space (home) that encompasses sleeping, washing and study areas with a separate entrance from the outside. The ground floor accommodates a large public space similar to an Italian Piazza (city) with living room, dining and kitchen activities serving the central living space.

https://atelierdehahn.com/architectural-education-modernism-the-incomplete-project-john-hejduk-and-jose-oubrerie/

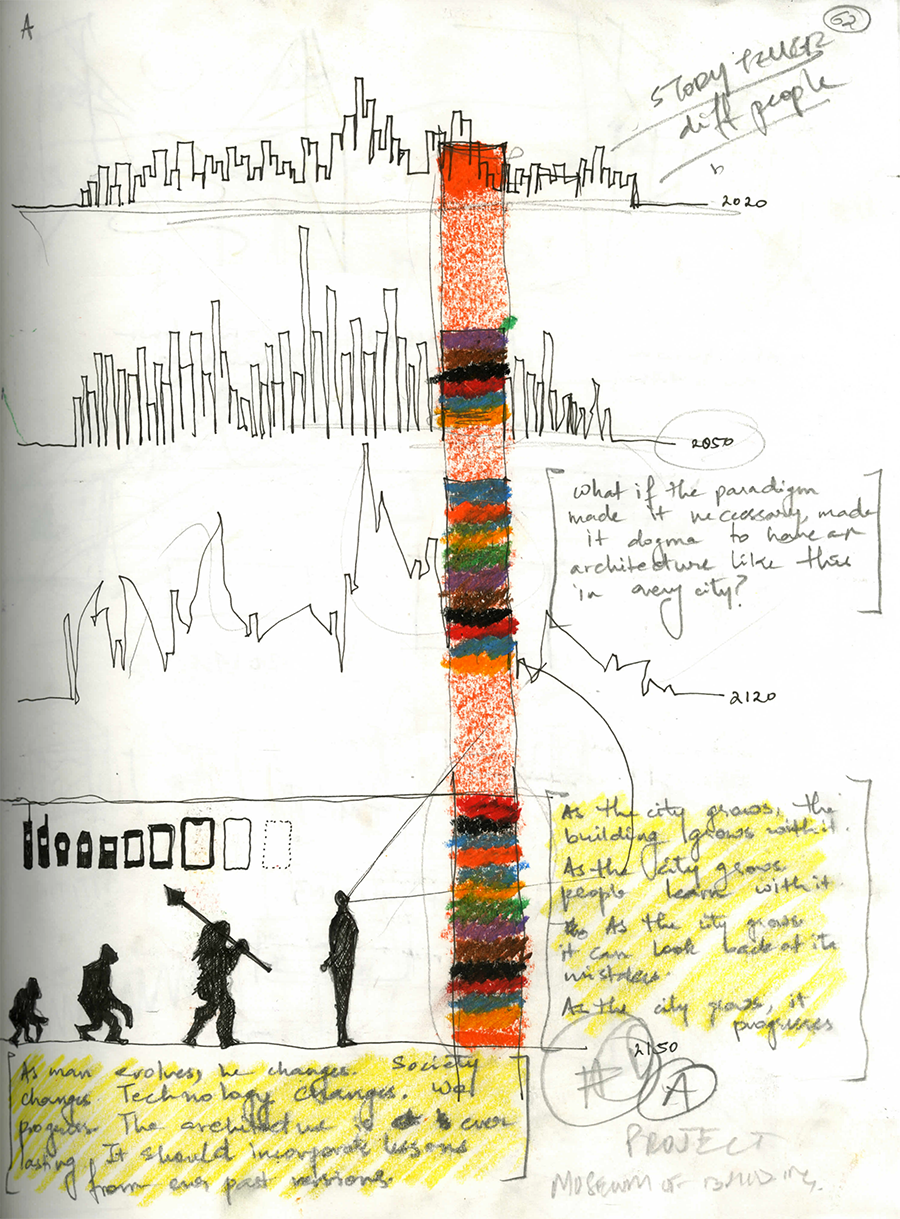

Example 4:

The final example is from a proposal I drafted in response to the 1988 competition, to redesign the library of Alexandria, Egypt, a library considered the most important in the ancient world. The thesis proposed a “city “ with vertical towers representing the different disciplines (architecture, art, medicine, philosophy, science, technology, etc.). While the base of each tower contained the existing collection of books, the growth of each tower was expressed through new building technologies as well as new methods to preserve human knowledge.

The overall organization was predicated on two major axis –Decumanus and Cardo as metaphors of the Roman principles of settlement, on which a permanent set of cranes would continuously build and expand the library vertically. From afar, the Alexandria library would be a living organism expressing the cultural aspirations or contemporary realities through the height of each tower.

For example, if the tower(s) of science were to dominate the landscape of the library, this would indicate the importance of the subject matter reflecting contemporary production of knowledge. Over the course of the library’s life, towers would dominate or be dominated based on the state of the collection of a particular discipline, thus showing the state of our human aspirations.

Additional blogs of interest on thesis

Architecture thesis, Part 2

Architecture thesis, Part 3

First steps in a student’s design process

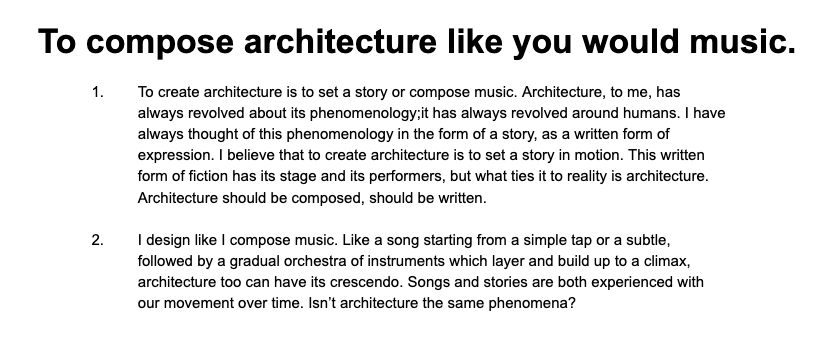

Thought about a project