Architecture thesis, Part 2. Throughout countless thesis critiques with architecture students, I always end up somewhere in the discussion asking the same question: What is your thesis? Their answers (yes, plural) are often evasive and timid, and suggestive of their initial unfocused interests as they struggle through numerous topics that are in their own right promising and robust.

All the students’ answers are legitimate, especially when the projects are at the beginning of a year-long thesis. At this point in time, I believe that it is quasi-impossible to precisely define a thesis, as the student’s interests are generally broad, spontaneous, and significantly autobiographical. As they progress, students usually get sidetracked by youthful distraction, virtual inspiration, and bravura; or find that their thesis interests morph into a set of meatier arguments fueled by research.

This interest in research occurs when students slowly regain their confidence and discern what is important in a thesis pursuit. This often happens after a self-imposed period when they feel the need to outperform themselves one last time because they believe that a thesis represents the culmination of their academic tenure (e.g., signature project) at the moment they are embarking on a promising professional career.

Faculty recognize the importance of this time in a student’s life. Especially since the thesis represents the first-time a student works on their own and is asked to set in place a program brief, develop an argument, a thesis objective, a design methodology, and how to present findings.

I mention this because, as a student, I had the opportunity to attend several of Mario Botta’s lectures. At one of them, he presented his completed 1977 project for the secondary school in Morbio Inferiore. Botta made a statement that he often only knows what he did when the project is completed.

For me, Botta’s tongue-and-cheek suggestion was that finding the thesis argument may be defined and re-defined over the lifespan of the project (as projects and the resulting spatial conditions of all the things experienced by the author); or, for a thesis student, during their year-long commitment. If a process is set in place that builds on previous ideas, one can then consider moving forward towards a successful thesis instead of constantly dwelling on what the thesis is about.

Architectural thesis?

When the academic semester is in full swing, faculty should have no qualms about requesting from a student a more in-depth description of their thesis, especially after students have had time to set in place the intellectual dimensions of their argument. During those mid-term discussions, and after some preliminary ground testing on the students’ overall ideas, I follow-up with a more pointed question: You just described a project or a thesis—but what is your architectural thesis? A long silence is followed by a confused smile, often with noticeable consternation, and on a few occasions, slight embarrassment that sets the question of the architecture thesis at the center of the student’s spatial preoccupations.

When, the dust has rapidly settled, my initial provocation jumpstarts a rich discussion about the pertinence of conducting a thesis within an architecture program. While the question about how to unfold a thesis has been addressed by me in a previous blog, I have since then learned from discussions with thesis students that my suggestions might have been taken as a linear way of thinking, one which was clarified in a second blog. There, I described possible first steps of any design process—be it a thesis or a project, which ended with the recommendation that students must learn to prioritize ideas based on their intuitive personal design approach.

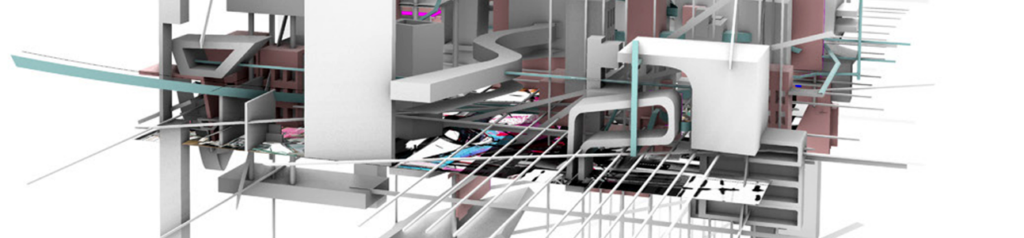

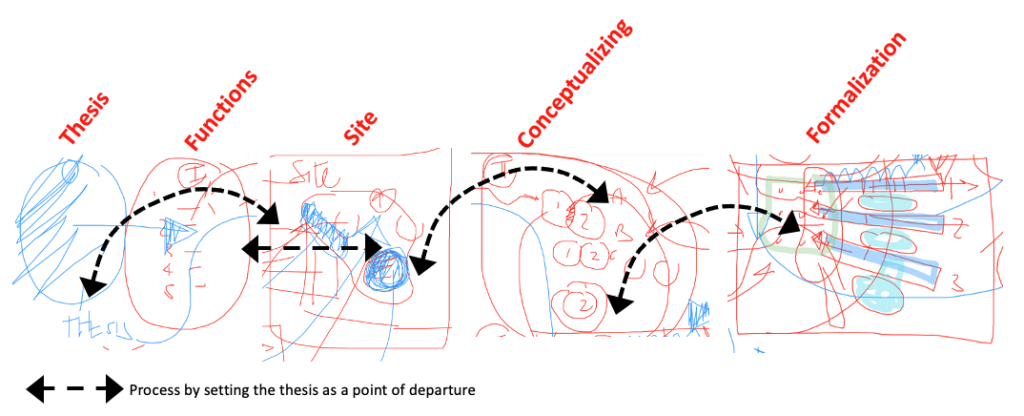

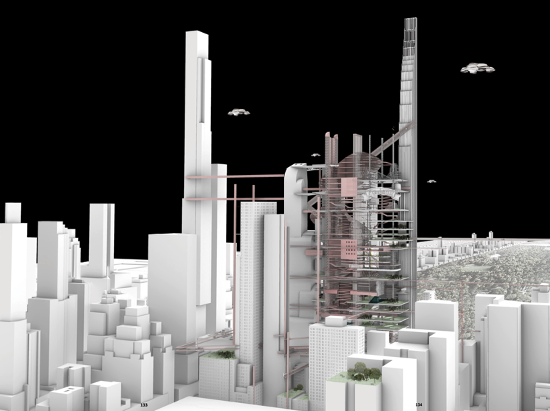

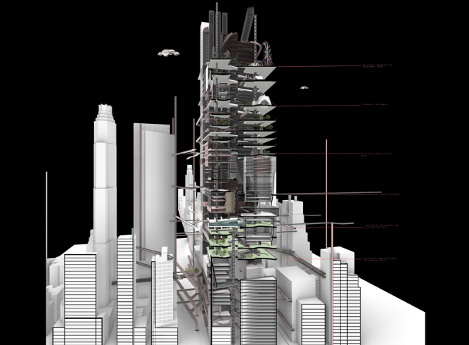

As educators, we tend to tell students during their fifth year that they need a thesis, a BIG IDEA at the onset of any project (Image 1, below). While this approach is somewhat myopic and does not build on the strength of each student (given my comment on Mario Botta), I believe that it is important that students recognize that a thesis idea can (or desirably should) emerge from multiple directions. Especially using various sources that are often incongruent to the initial thesis idea.

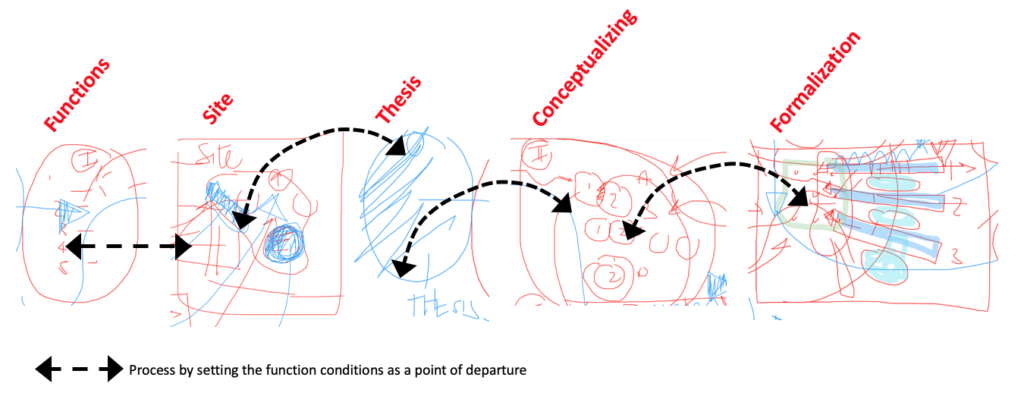

For me, and this is a personal design approach, I favor at the beginning of a thesis to include a function that will hold my attention, which then immediately calls for a program; an initial reading of the site and its context; an interest in materiality; and a basic structural system that allows me to structure spaces that I envision. All of these design impetuses typically contribute to negotiating a spatial organization, while giving a fall back to jumpstart a project rather than desperately trying to find the ideal idea. Of course, other impetuses may be a driving force for students.

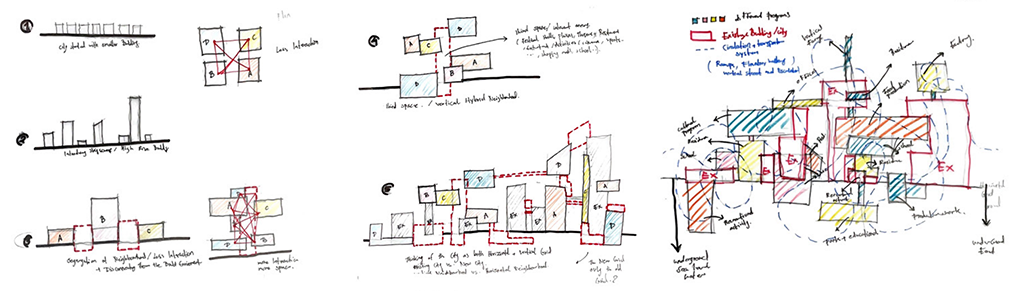

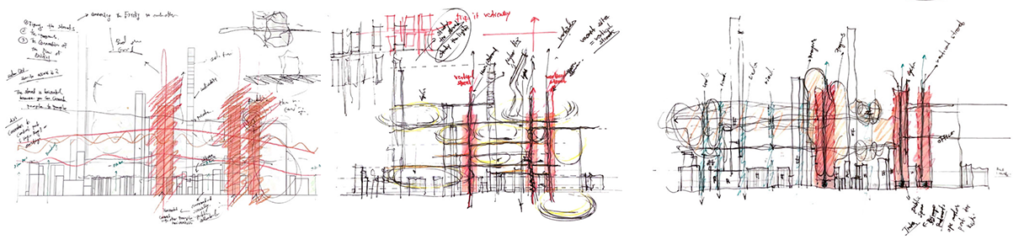

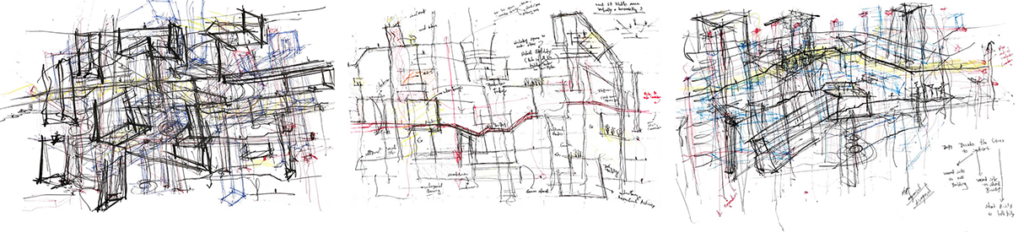

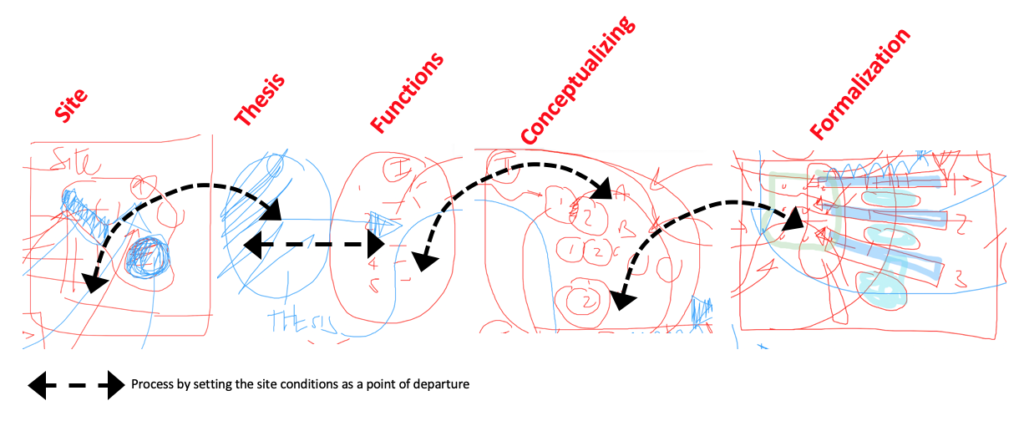

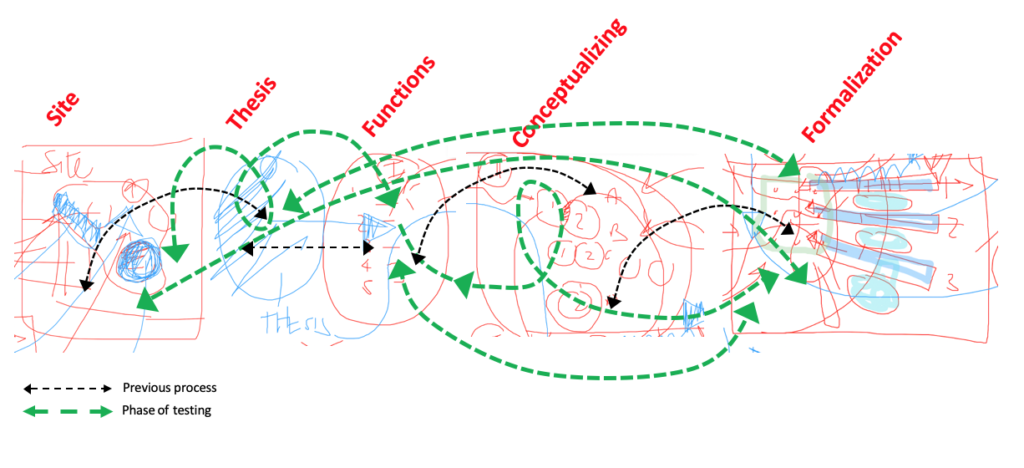

The following diagrams (Images 5, 6, 7, below)—although exclusive in their focus on specific topics—suggest points of departure to unfold multiple paths; all promising ideas that can lead to a successful final thesis outcome. I diagramed these three processes, to show that a thesis can be the motor of the project, or, in example 2 and 3, emerge from other initial preoccupations such as site or function. Of course, with experience, a multi-layered back and forth is perhaps the best process to develop a project, a THESIS (Image 8, below).

What attitude to have when exploring a thesis?

For this blog, I decided that rather than further explore what an architecture thesis is, or outlining multiple processes that take place when working on a thesis—particularly as among colleagues we understand that there is no common definition regarding a thesis or process—I decided to focus on what attitude a student should have to be able to complete a successful thesis project. Thus, the following two thoughts offered in no specific order.

Wanting to say something

I start from the preconception that architecture and its thesis has a primary interest in space. Space, not as simply a concept, but as a complex set of coordinated and sequenced moves that suggest meaning through the design of an artifact, thus requiring a critical position on whoever the end user is. This is accomplished by exploring the five senses in perhaps an untraditional manner—be it paper architecture or a system of notifications leading towards the promise of a building, or at a minimum, a conceptual idea of a space (Image 9, above).

There have been endless questions asking if meaning can be imbued on an artifact by a designer or if meaning is solely a matter of the user’s experience—a question that has its parallel in the words authenticity and calling. This parallel finds its origin in the Romantic idea: if an object is either beautiful in its own right or acquires this quality by the user’s sense of beauty projected on the object. At this moment, I trust the student to determine their position on this matter.

The above statement about creating space may seem superficial or banal, but I have seen over decades of teaching that many architecture students forget that creating space IS their art form. At times, sociological or philosophical implications take front stage, thus there are moments in a student’s thesis project where an inability to translate those weighty preoccupations into space become insurmountable. This is because the ideas become more powerful than the tedious negotiation of translating those ideas into space.

Multilayered interests are vitally important in a design process—especially when dealing with complex human thoughts. However, students often appease their curiosity through research without returning to the initial idea, simply researching it to death, often at the expense of the unique richness of architecture. It seems obvious that while working on their thesis, students need to have already acquired a solid background in developing space and, most importantly, have something to say about the new spatial organization they are designing and the sequences that will carry a project over their entire fifth year.

Figuring out what to say is essential, because without intellectual conviction, a thesis – a BIG, BOLD and COURAGEOUS idea about space – students might end up with a very good project, but not a thesis. In all the schools I have been affiliated with, faculty have had honest debates about the ill preparedness of some of their thesis students, thus the question if and how faculty should offer an alternative track to engage those students during their senior year. Frankly, I feel that no decision will ever emerge from these discussions, as the question should always be based on a democratic approach to education centered around the students.

If faculty triage students towards a thesis versus a project—for all the healthy academic reasons that should solely focus on the student’s wellbeing (note the medical jargon here, which I believe needs to be addressed in a post-Covid era) —any forced assignment (thesis or project) will create students who legitimately feel that they are being ranked first or second, a policy that should never apply to any student.

Although one must be sensitive when engaging in such a conversation, these faculty exchanges are necessary to develop the strength and opportunities of a thesis versus a project. I often argue that a student is not lesser because they wish to conduct a project, as often they will find within their process the nature of their thesis. Let’s be frank, this is how architects mostly make statements in their profession (e.g., Mario Botta).

Being committed . . .

Students must be committed, passionate, and dedicated. This might seem a tacit understanding for both faculty AND students, but I have observed that during the initial foray into a thesis argument, students get easily distracted. While they draw from learned and often mastered foundations over four years—a time in which they should have developed a repertoire of their own ideas—many students are challenged to commit to an idea. Of course, the greatest ideas range from pure intuition to a deliberate process-oriented design thinking.

In all cases, I feel that the difficultly is that while the students need to continue to reach higher than they ever thought possible, they are often unable to sit down and proceed with a topic. As an American idiom correctly states: the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence. This pursuit of something unique can be detrimental to a healthy departure leading to a thesis.

I believe that there is a balance between tradition and innovation, influences through precedence and personal inspiration—e.g., rendering traditional ideas in novel way while shouldering designs on those that they have come to admire and respect. This leads any project, especially a thesis topic, to create a meaningful disruption with the past, all the while developing a very personal identity that can be explored during the thesis year. Ideas are multilayered and emerge from multiple venues that often reflect past preoccupations rooted in previous projects. Moving ideas and strategizing them simultaneously in one direction might be a first line of defense toward being committed.

Conclusion

While I have promoted that any project needs to carry a thesis, or at least a big idea, there are countless factors that make a thesis. Ask any of my colleagues and you will get diverging ideas. Yet, having students be bold, daring, and courageous, may be something that needs to be continuously stressed beyond the insistence of a ‘true meaning of a thesis’. To be authentic in research, to remain playful in design pursuits, to be curious about the unknown, to be compassionate for ideas, and to be genuine in understanding what YOUR architecture should be, should always eclipse the pressure of how a project is perceived by others.

Shouldn’t a thesis remain first and foremost an intellectual manifestation of a student’s creativity?

Additional blogs of interest on thesis

Architecture thesis, Part 1

Architecture thesis, Part 2

First steps in a student’s design process

Thought about a project