National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. There are many moments in one’s life where emotions take over, but few are so powerful that no matter what you think or what you do, feelings, sentiments, and memories become one in mind and body.

National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. There are many moments in one’s life where emotions take over, but few are so powerful that no matter what you think or what you do, feelings, sentiments, and memories become one in mind and body.

In the spring of 2018, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, located in Montgomery, Alabama (USA), opened its grounds to the public. By the time of my visit a few months later, countless national and international editorials had covered this public place, contextualizing the importance of the opening of the memorial in America’s history. Honoring the past has never been an easy journey, as it forces all sides to recognize and own responsibilities of past actions based on our collective consciousness -in this case the history of American slavery in the South, and the deliberate lynching and racial terror inflicted on men, women and children of color.

Image 1: Sculpture on the Memorial grounds, Antebellum Mansions, view of the steel columns (author’s collection)

While words remain powerful tools of expression, as an architect, I favor translating ideas into space. But how does one achieve a sense of place for the commemoration of such brutal events? In Montgomery, it was done with restraint and suggestive power. Located immediately to the west of downtown, the site occupies two-thirds of a city block between Caroline and Holcombe Streets. Non-descript homes surround the site, with occasional highlights of beautifully restored antebellum mansions. I entered the memorial through the discreet entrance building.

The surrounding grounds were carefully curated, with information and sculptures punctuating my ascent to the centrally located square pavilion designed by MASS Design Group. The gradual internalization of what I saw and read on that walk could not compare to what I would experience through all of my senses after entering.

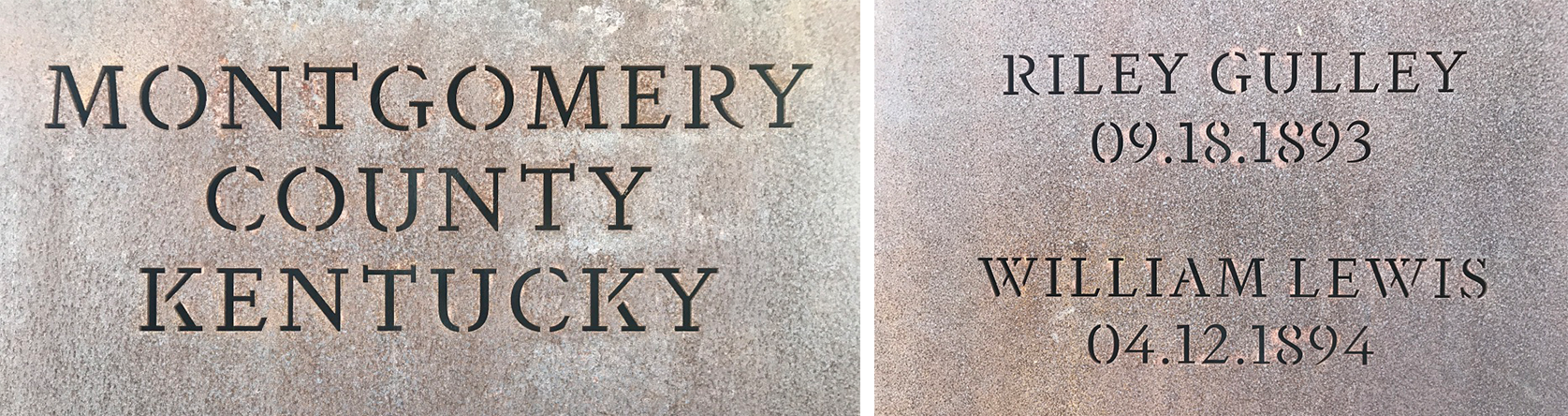

In the first of four long and broad open-air corridors that form the covered pavilion, I was face to face with a field of oxidized rectangular columns. On each of them I read inscriptions stating the state, county, names of the deceased, and dates of lynching. Sadly, I found too often the names of the deceased replaced with a single, haunting word: Unknown.

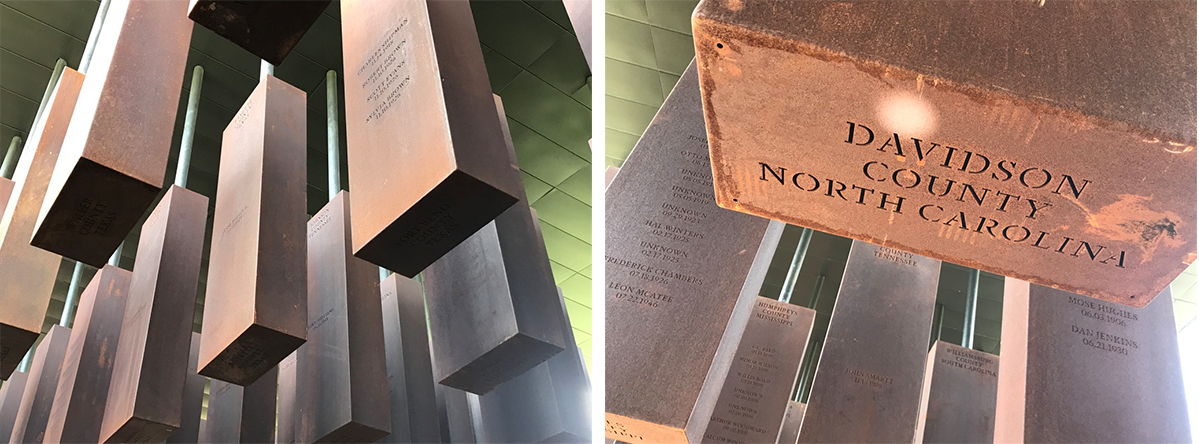

There was an immediacy to the visual density and purpose of the place, and an ominous sense of drama was created as the strong mid-morning light cast shadows on the wood flooring. While situated near the ground, the oxidized Corten steel columns seemed to be suspended from the ceiling by thin tubes. After a closer look, I realized that they, in fact, did not touch the ground, confirming a feeling of inevitably of non-return. And yet, there was something comforting; each human column had its largest dimension facing the path of my visit so that I felt I was in front of individuals, a person behind each name that I could touch, feel, and hug.When I arrived at the end of the first corridor and turned the corner, views to the inner courtyard subsided.

The floor began to slope below grade and the steel columns seemed to slowly rise above my eye height as I descended. In the middle of the journey, my eyes were drawn to the end of the space where a horizon was created by the bottom of the columns and the top of the concrete retaining wall. A thin sliver of light emerged, rendering visible the lack of connection between columns and earth. From there, the names and death dates of these men, women and children were above my gaze and emphasis was now on the underside of the columns where the inscription of county and state remained clearly visible. Here, each individual became memorialized as part of a collective memory.

At the end of the second corridor, I took another right turn and was confronted by hundreds of columns, a vista where each hovered high above my head, all the while conveying an incredible sense of weight. I could not escape feelings of guilt in front of the horrors that men inflicted on other humans. My previous spatial experience of descent was like dying and returning to earth as I was now physically below grade, while those who suffered and were unjustly lynched, rose to heaven.The culmination of my journey inside the pavilion occurred in the fourth corridor in front of a wall of water.

Like tears, the water gently covered an inscription which began: Thousands of African Americans are unknown victims of racial terror lynching…. The surrounding benches offered a moment of repose to reflect on the experience. The floor was again horizontal, stable and espousing the ground.

Image 7: actual and metaphors of shackles (author’s collection)

Upon exiting the pavilion, I was reminded of the powerful sculpture created by Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo located at the entrance. The traditional sculptural expression of human bodies suffering under the torture of slavery could now, after experiencing the pavilion, be measured against the abstract steel columns. Figuration and abstraction worked in unison. Both the abstract content within the pavilion and the outside figurative sculpture participated in new connections. One that has not left my mind is the detail of the pavilion’s railing anchored to the floor, an abstraction of the shackles attached to the feet of the slaves in sculpture. Architecture speaks forcefully about this story.

The creation of spaces has always been an extraordinary tool to lend physicality to a vision, a model of life, or simply a way to offer answers to even the most mundane functional ideas. While context and the siting of a building, its form and geometry, its materials and construction techniques all partake in the success of any project, experiencing a place with a higher calling means transcending the physical construction as one’s body moves through the stories told through space.

Additional blogs of interest:

The Igualada Cemetery

National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama

Architectural Education: Sketching on a field trip. Part 1

Church facade in Ticino, Switzerland: Part 1

Church facade in Ticino, Switzerland: Part 2

For additional images, please visit NationalMemorial