Ever since the Grand Tour, architecture students have explored buildings in situ through formal and informal learning opportunities outside of the traditional campus setting. Whether semester long international travel programs or short design studio field trips, faculty recognize these experiences as vital curricular moments that add meaning to a student’s education, especially when sketching is part of the act of observing. Beyond the pleasure and exoticism of travel, whether to nearby or distant places, learning first hand from buildings remains rewarding and memorable. It is a moment when many senses come into play, and most importantly, brings forth intense visuals that offer students a way to confront their academic understanding of a building with their on-site experience of it.

Ever since the Grand Tour, architecture students have explored buildings in situ through formal and informal learning opportunities outside of the traditional campus setting. Whether semester long international travel programs or short design studio field trips, faculty recognize these experiences as vital curricular moments that add meaning to a student’s education, especially when sketching is part of the act of observing. Beyond the pleasure and exoticism of travel, whether to nearby or distant places, learning first hand from buildings remains rewarding and memorable. It is a moment when many senses come into play, and most importantly, brings forth intense visuals that offer students a way to confront their academic understanding of a building with their on-site experience of it.

Gerrit Rietveld

As an architecture student I did my pilgrimage to Utrecht, The Netherlands to visit the famed Schroeder House of Dutch architect and cabinetmaker Gerrit Rietveld (1888-1964), only to be disappointed by the sight of the building at an unanticipated scale—much smaller than I had imagined. My view of this house was also disturbed by the presence of a ubiquitous 1970s elevated highway that was far too close to this icon of modern architecture; the highway was to me an affront to the integrity of the building (Image 1, above).

Despite these disappointments, I was able to appreciate the power of the building, and, in particular, how it so profoundly challenged what I had learned in the classroom. Slides, books, magazines, and the professor’s erudition and passion for the building had forged a precise image that was, I believed, somewhat educated. I was appreciative of the underpinnings of the architect’s life, and how his interpretation of the art movement Neo-Plasticism (De Stijl) transformed into an architectural built artifact. Most importantly, I appreciated how the graphic drawings translated Rietveld’s radical vision of a historical building type as a new model of domestic life. All of these thoughts embodied my knowledge and comprehension of the building before I arrived.

Yet, at that time and now decades later after many site visits, my understanding of the Schroeder House, while certainly accurate, was incomplete; my visit gave the artifact new meaning by adding first-hand impressions that were formed on the larger site context, with first-hand experience of the materiality and their aging to name but a few of the things I learned. Of course, in this case, I could not fail, while conducting my own promenade architecturale around the house, to remember the historical circumstances in which it was designed. I confronted them with a deeper reflection on the contemporary meaning almost five and a half decades after the building’s completion in 1924.

Meaning of drawing at a site

What is ironic and difficult for students to understand is that any site visit is both a point of departure and a summation that wraps up an appreciation about a building. Any site visit is also a new point of departure: our comprehension that any historical artifact (i.e., precedent) serves to inform us about how we may resolve similar programs within the contemporaneity of our times. This dual appreciation of existing knowledge and one of a heuristic on-site discovery of the artifact, becomes an essential ingredient for any successful site visit.

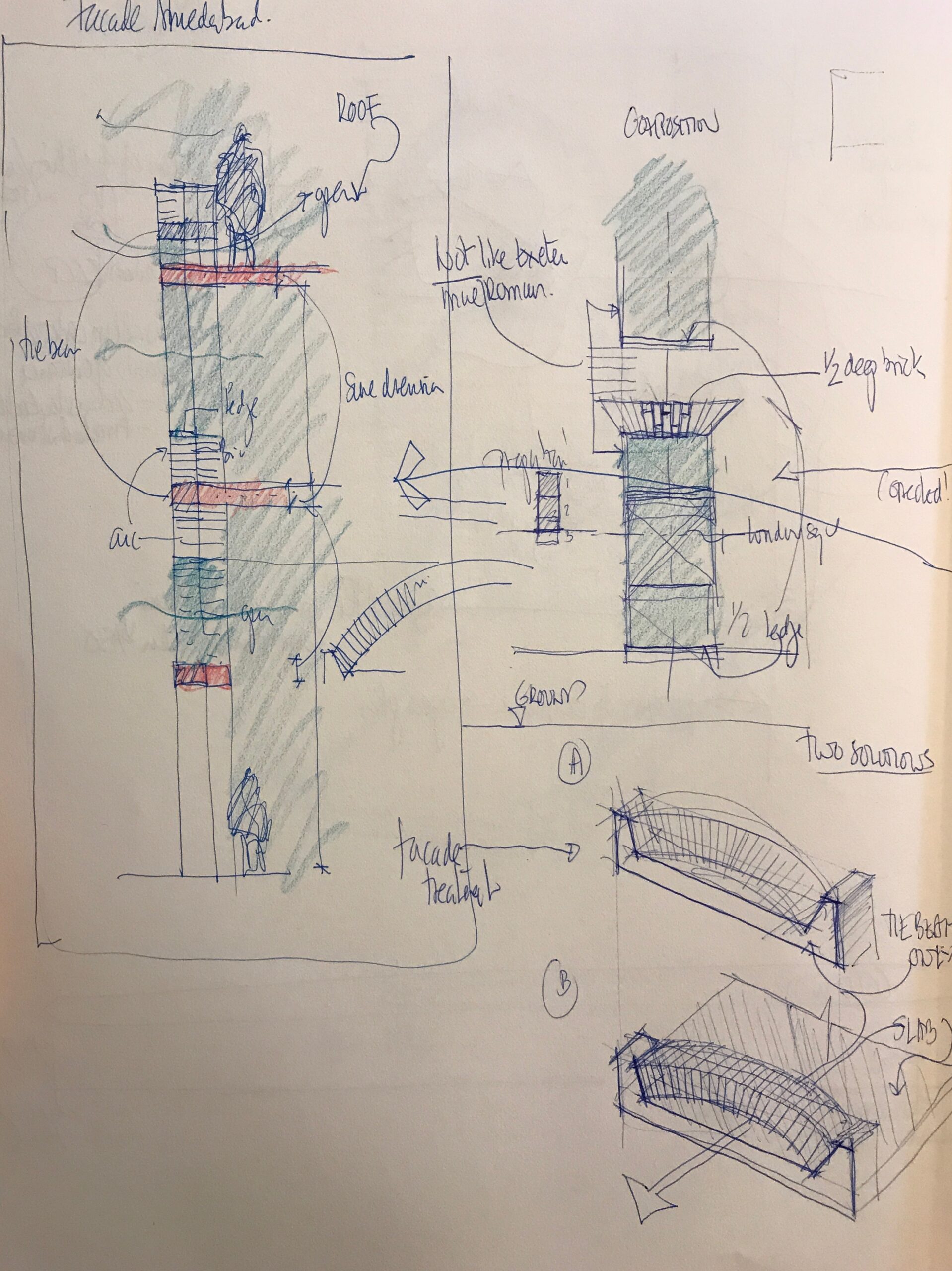

1. Carlo Scarpa

Fast forward to today. More than ever, I believe that students need an on-site experience. While social media, YouTube, chat rooms and other forums create easier access and perhaps a more comprehensive enjoyment of the building, they do not necessarily provide an in-depth understanding that brings learning to the forefront of the experience. Case in point, when accompanying students on field trips, time after time I see them full of anticipation before the visit, then, upon arrival, they simply plunk themselves in what appears to be the first and best place in order to make a drawing in their sketchbook. It is the Pinterest habit translated into an architectural attitude that perverts a humanistic approach to the visit. Drawings are curated to impress themselves, their faculty, or family back home, and often fail to translate a researched understanding of what is in front of them.

2. Louis I. Kahn

Of course, to draw and to observe is different from the need to create an image—a representation that often lacks the discipline that furthers the recording of first impressions. Yes, recording impressions is critical as this translates ideas, feelings and opinions, and if the recording of impressions is genuine, I argue that they are potent because they are autobiographical and translate the in situ experience.

But how can this be done in full honesty when a student has not walked around and in the building to experience it? It seems that somewhere in the process of understanding a building, photographic drawings, rather than an informed conceptual understanding of what is seen, emerge as a priority. Too often, when discussing their sketches, I tease the students by mentioning a particular moment that was important for me. Many students, intrigued with my comment, share with me that they have not even entered the building, as the outside first impression is what struck them, and made them sit down, pencil and sketchbook in hand, and with all the talent and fervor, make a show-off drawing.

I always found this attitude curious as this first impression could have been recorded with their cell phone camera and drawn later when a conceptual understanding of the building and context had filtered through the first impression. In today’s day and age, elevations and plans can be instantaneously uploaded or studied prior to any visit and lived intellectually prior to being confronted physically through all of the senses. Why not take advantage of that and complement it when on site.

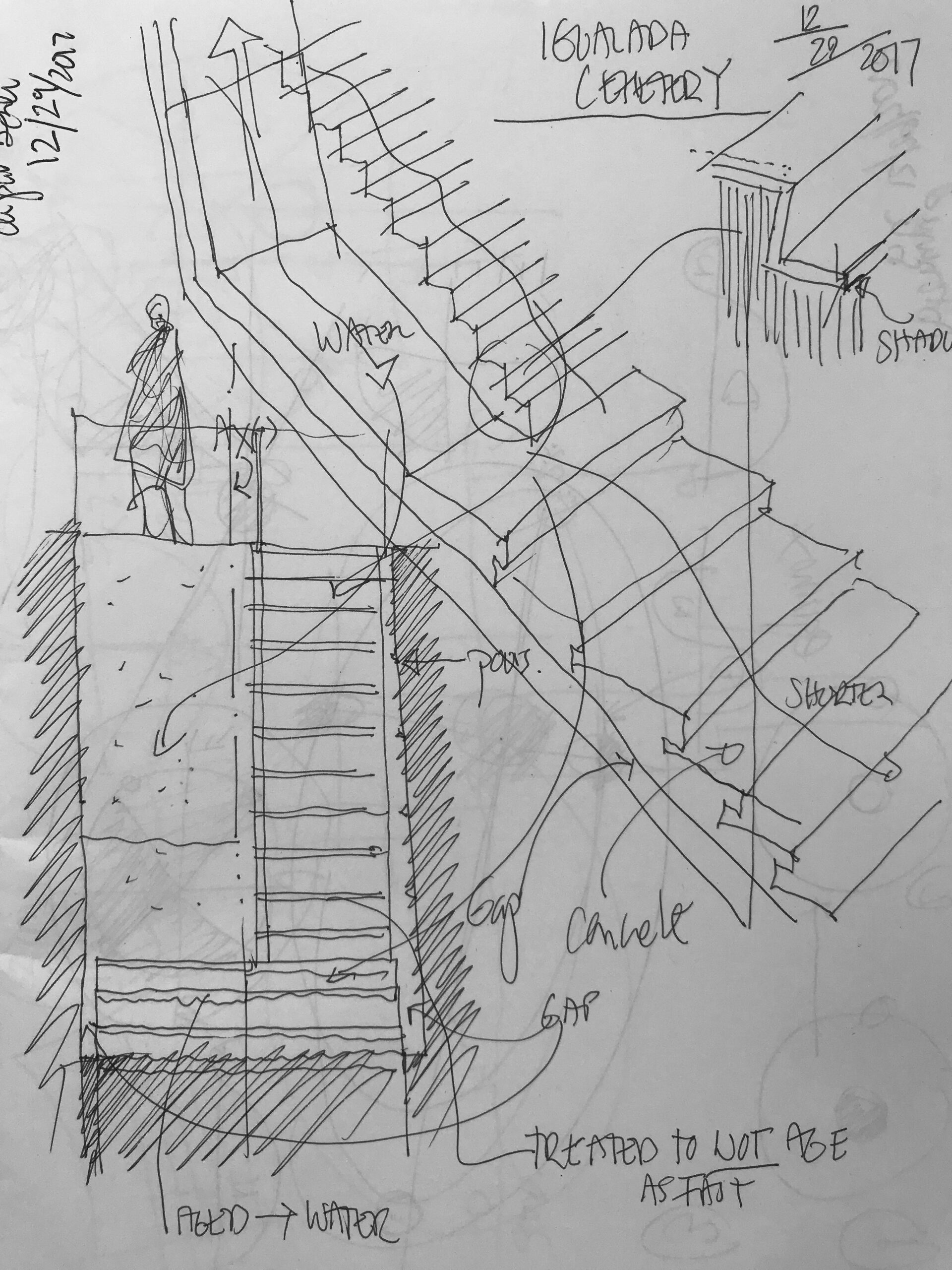

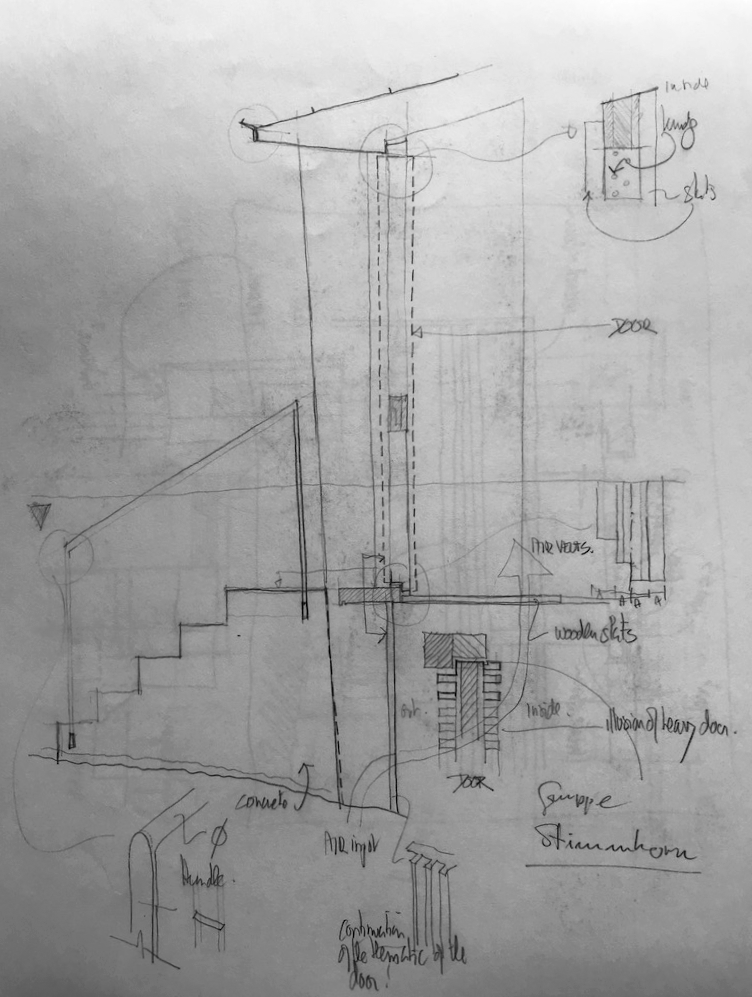

3. Enric Miralles and Carme Pinós

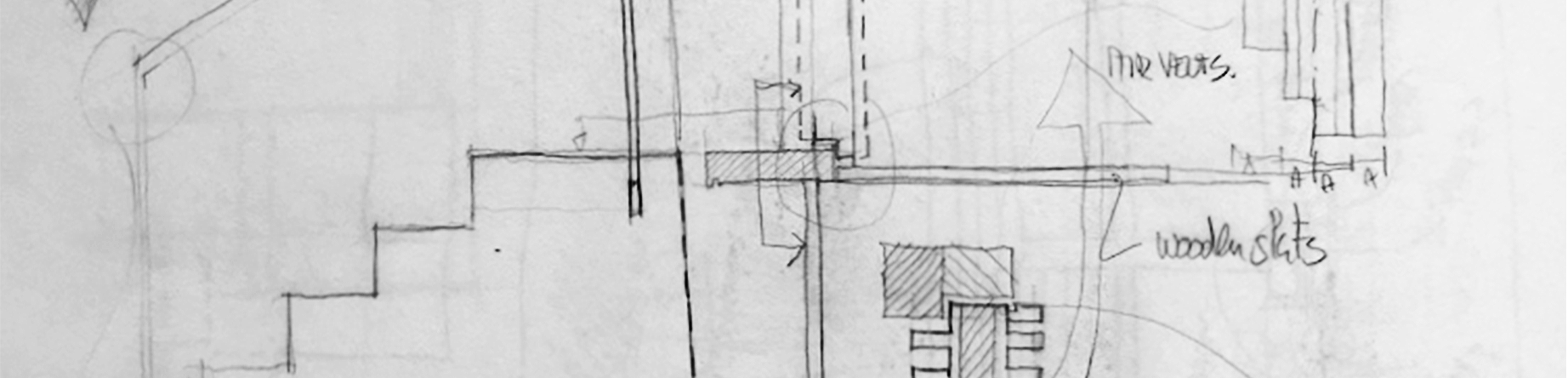

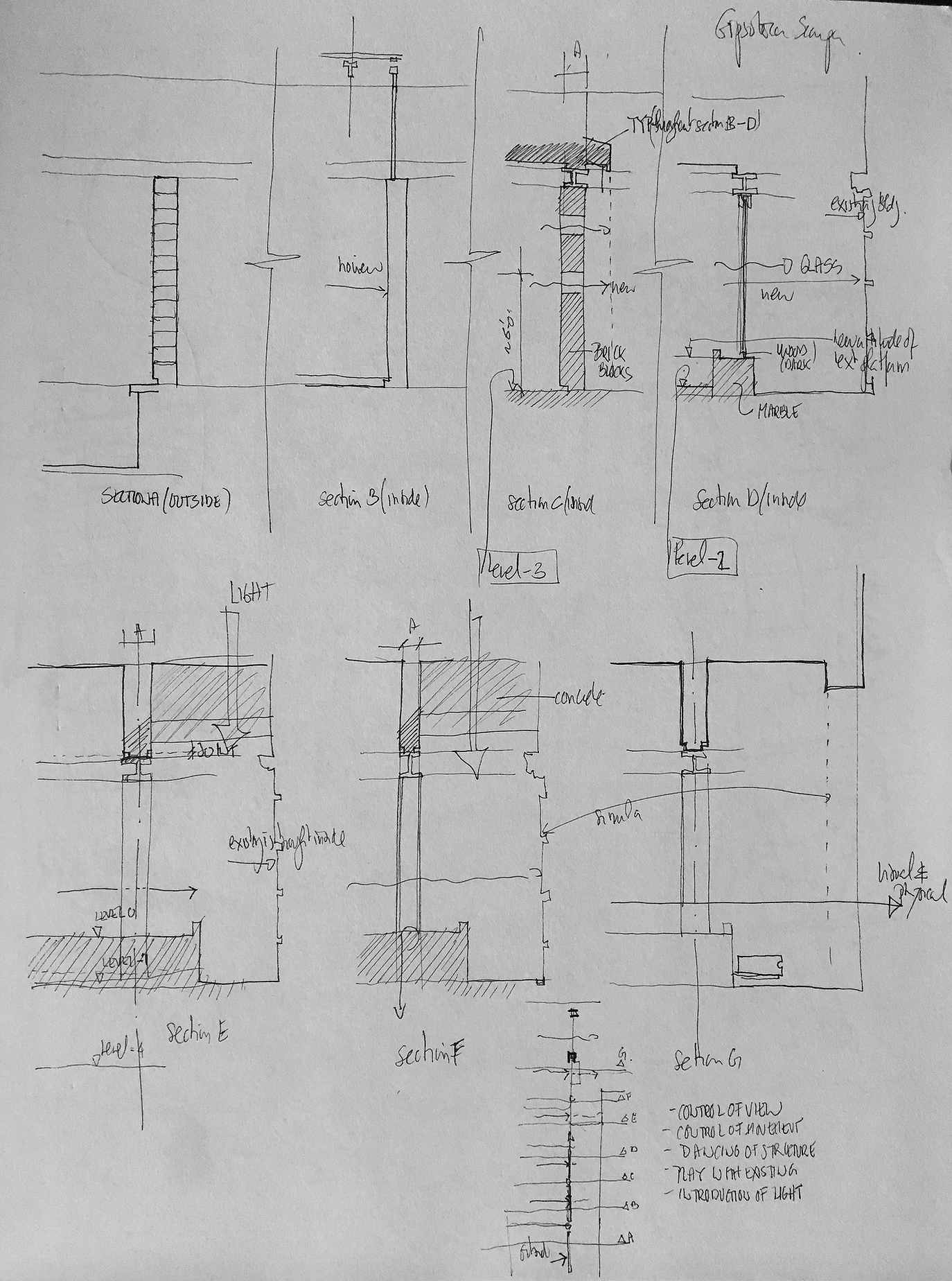

Experience shows me that few students are trained prior to a field trip to see drawing as a disciplinary endeavor. Not to record what they see, but to observe and use their drawings, conceptual sketches, and diagrams as a pretext to develop an architectural discourse on the nature of the object itself; a way of understanding process rather than product (i.e., image). This is one reason I personally enjoy understanding systems of construction during site visits, a spatial device that eschews the need for imagery to the benefit of understanding how things are constructed and detailed.

4. Peter Zumthor

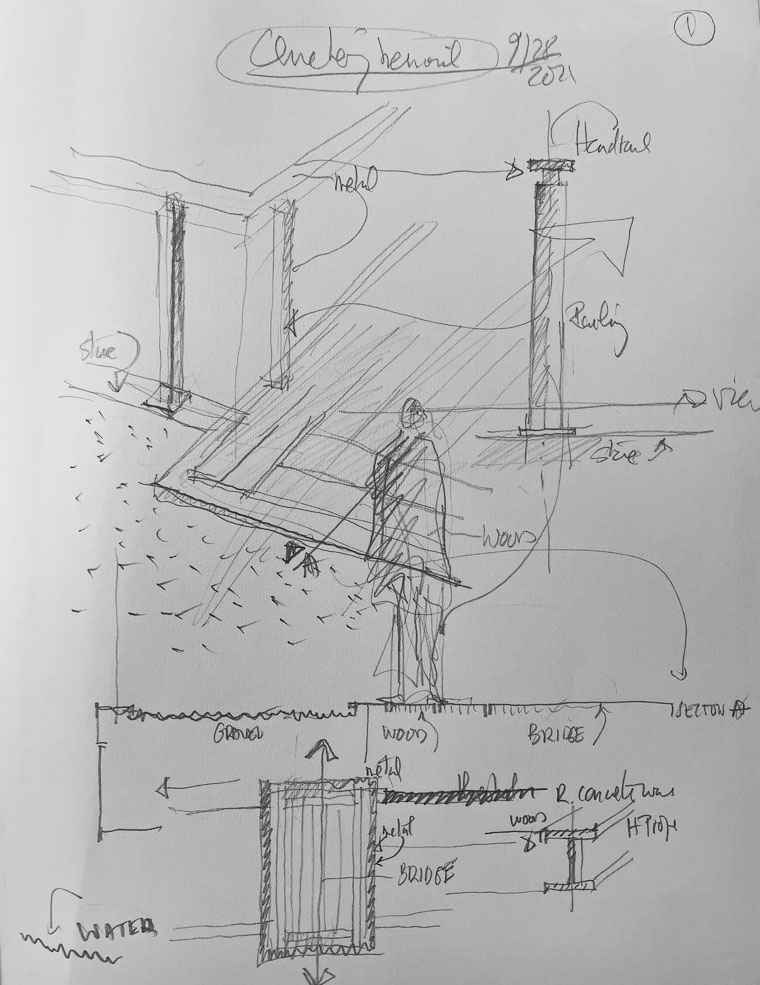

5. Sherwood Memorial Park, Salem, Virginia

Added, 11.06.2021

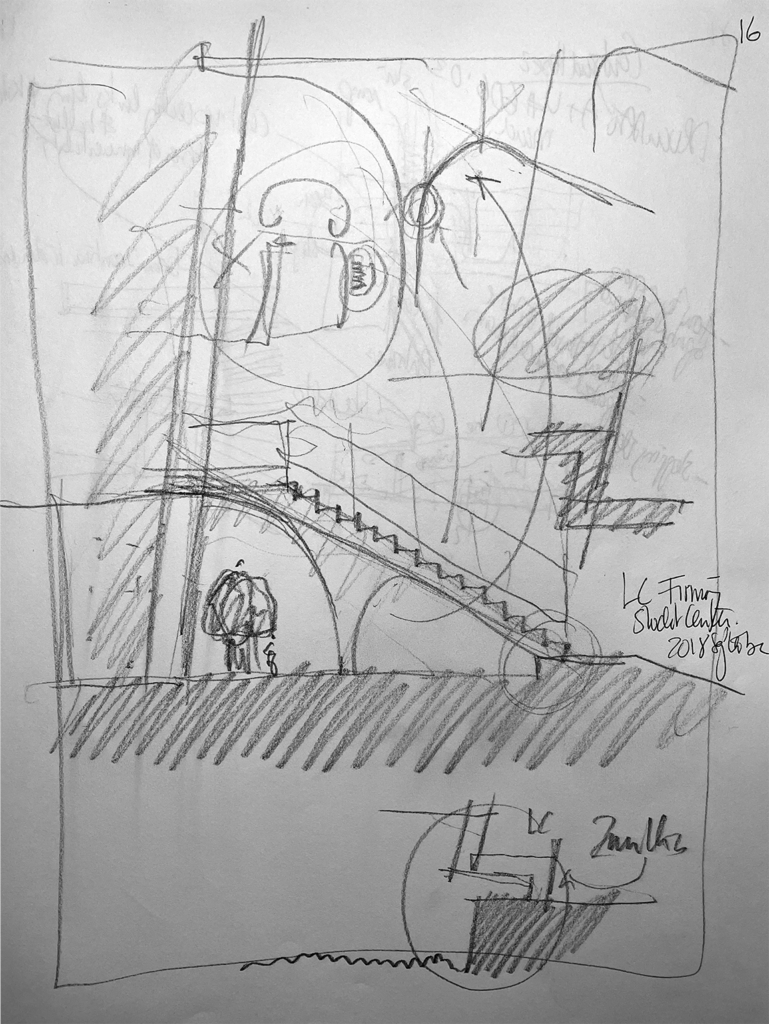

6. Le Corbusier

Added, 01.02.2022

Epilogue

Rekindling memories of my studies, I owe my attitude to site visits to Plemenka Soupitch, my favorite first-year professor. As she knew that I loved to travel and visit architecture sites, she offered me rolls of 35 mm slide film to record construction details of buildings. While the images would be duplicated to enhance the school’s vernacular collection, I was able to keep the originals.

When documenting details of how buildings were assembled, I remember that photographing them failed to meet my curiosity. I slowly gained an appreciation of how things were built, especially during a trip to Rome where I developed an eye for sketching how things came together. The vestiges of Roman walls fascinated me, in particular those called Opus Reticulatum, which were made of stone and brick, secured by concrete in the interior formed by parallel exterior coursework, where corners expressed the need for static reinforcement.

While I could not fully see those details and others at the Forum, I came to speculate on their assembly, and more importantly the chronology of their construction. Drawing my findings, first as a naïve understanding, then through experience and more confidence, I gained an understanding that construction was integral to the act of designing.

To “look, observe, analyze, document, touch and sense… an apprenticeship in time” has allowed me to fill my sketchbooks with details that I still find invaluable to my in situ experience.

Architectural Education: Sketching on a field trip. Part 2

Architectural Education: About sketching -an iterative process. Part 2

Architectural Education: About sketching -an iterative process. Part 1

Architectural Education: What issues does one encounter when sketching?

Architectural Education: Some thoughts on sketching by hand