About sketching an iterative process, Part 1. I believe that any architectural project starts with a concept, and let us call it to have an idea. As humans, we communicate ideas through sound, smell, taste, touch, and VISION. There is an English adage, A picture is worth a thousand words; a saying that suggests that complex ideas may be expressed by a single image transmitting the essence of the idea.

For architects, there are a number of means of translating ideas into space, however, sketching remains one of the most evocative skills in our kit-of-parts of visual tools. Ideas may be precise, logical and geometrically determined; or shapeless, metaphorical and imprecisely expressed. Regardless, how does one start to sketch, and in particular how does one practice drawing in an iterative manner, especially if one is a beginning architectural student?

First thought

Let us recognize that we all have an initial anxiety when we start sketching. Any new beginning is about the immediacy of facing one’s own limitations. What medium to use, how to hold one’s pen, and the fear of a blank sketchbook staring at us, are familiar moments for any student. This self-imposed pressure may explain the first stumbling block: the desire for perfection. There are other worries, including how to conceptualize an idea, or how to know what to draw before committing it to the page.

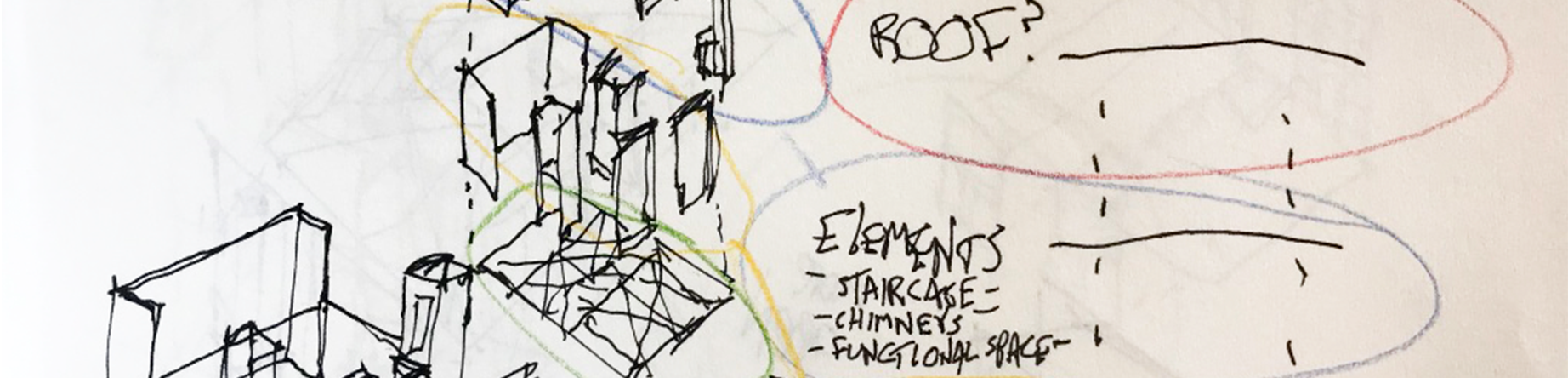

Anything that we sketch will appear imperfect. Let it be, as our first lines, shapes, or any accompanying ideas in words can always be fixed. With time and confidence, we learn how to coordinate our mind, hand, and drawing so that sketching becomes second nature, even if one does not always know from the outset what the drawing is about.Image 1: sketches by a student (author’s collection)

Second thought

Critical to this endeavor is to acknowledge that sketching is often not linear, even if there is a line of reasoning underlying each of the steps. Sketching is first and foremost a design process that evolves naturally through improvisation and iteration. Rather than following a predetermined path, the guiding force should allow one to develop free associations, letting many different and unconnected ideas seep into the page. Students should trust their instincts in their approach; there is a logic behind this intuitive way of sketching. And yet at the same time, while acknowledging the idea of imprecision, one continues to seek vigorously to do one’s best, thus the need to find a happy medium between imprecision and perfection in the search for clarity of one’s ideas. This tension should become the locus of any new beginning.

Third thought

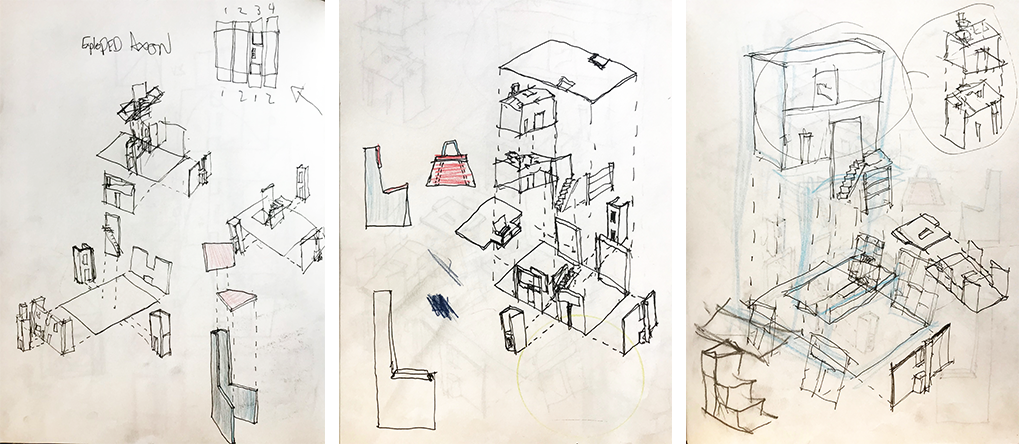

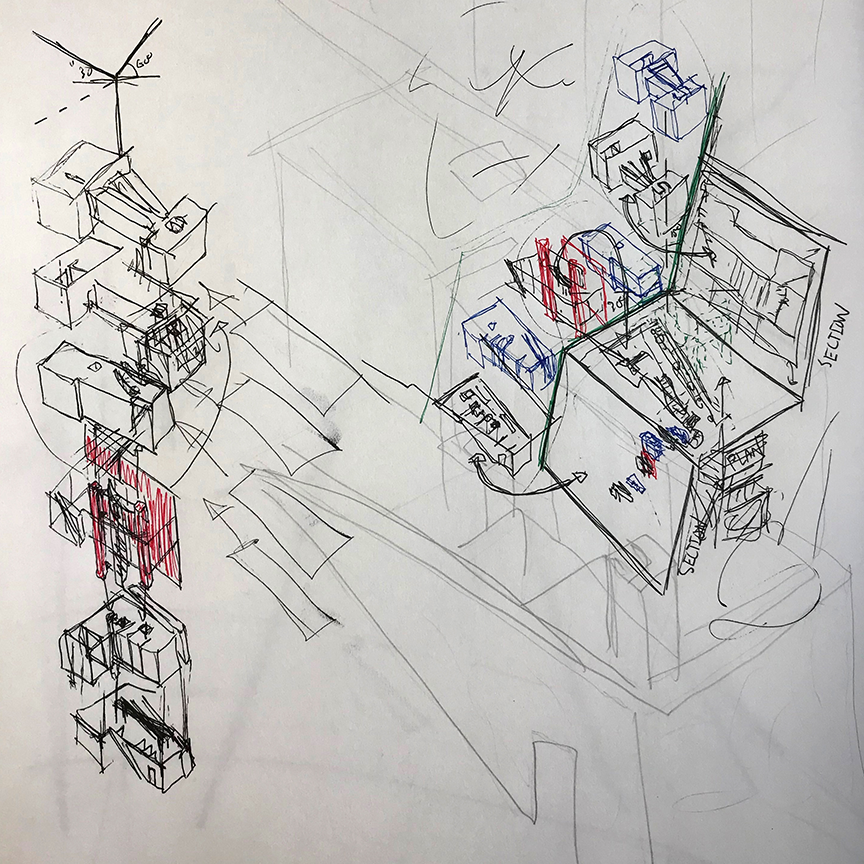

Don’t seek ‘the singular and perfect sketch.’ The true intent of sketching is to work out ideas while generating and communicating a design intent. This process is iterative and translates a sequence of thoughts onto paper, while simultaneously speaking back to let the drawing suggest new paths of inquiry. This might seem counterintuitive, but this process is like a conversation with the sketch. In fact, as soon as one finishes a drawing (i.e., lifting the pencil to pause and think), immediately move to another sketch to further the first idea, to adjust any visual misunderstandings, or to simply explore new concepts that were suggested in the initial drawing.

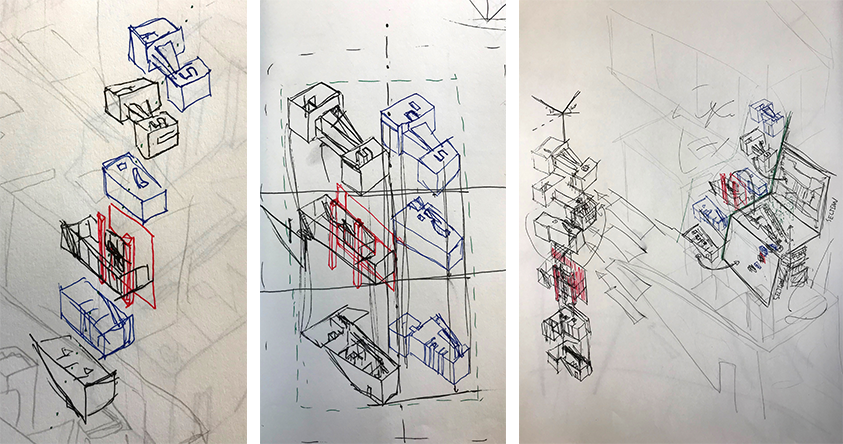

This creative process is often referred to as ideation. With practice, the pencil will sing (meaning work more loosely as you draw) and move faster than is possible to think. Contrary to a perfect sketch that carries the weight of something that is seemingly predetermined, the iterative process allows rapid experimentation and innovation in exploring ideas.

Approach to sketching

The above three concepts underlie a particular approach to sketching, one that enriches any design development and allows a student to compare and contrast between several design variations and possibilities. Testing ideas in this form is essential, and is particularly rewarding when looking back at one’s own drawings. A coherent line of reasoning slowly materializes, one that synthesizes the artistic balance between desire and need, both as a conscious and unconscious act of drawing. In the end, the sketches will convey the author’s process, their findings, mistakes, and opportunities.

Allowing modulation of line weight -ranging from consistent thin and precise lines, to rough and blurry markings, a variety of shapes, color, texts and other systems of notations – is a process that approximates our initial idea to one that searches to be close to an ideal.Image 3: sketches by a student (author’s collection)

Conclusion

The above three sketches represent a project given to my second-year architecture students. At the end of a case study of notable houses throughout the 20th century—from Le Corbusier (1887-1965) to Rem Koolhaas (1944 -)—one of the assignments asked students to diagram concepts discovered during their research, and express them in an exploded axonometric. Having honed the basics of an orthographic projection, the question remained what and how to represent a series of ideas in an abstract way, while assuring readability of their findings. The images of these two students suggest an already clear and rigorous approach to sketching as an iterative process.

- Louis, I Kahn, Margaret Esherick House, 1959, Philadelphia, USA

- Rem Koolhaas: Maison D’all’Ava, 1991, Saint Cloud, France

Architectural Education: About sketching -an iterative process. Part 1

Architectural Education: What issues does one encounter when sketching?

Architectural Architectural Education: Sketching on a field trip. Part 1