Peter Zumthor, the chapel at Sumvtig, Part 1. Whether you are a student or an architect, you will remember visiting a famous architectural work for the first time. Confronting one’s ‘academic’ knowledge with an in-situ (often through sketching) experience often results in moments of epiphany followed by long lasting memories. Architecture has a tremendous physical power in orchestrating the five senses, eliciting different emotions, and often leaving us speechless in front of the grandeur of a masterpiece.

The experience of architecture

In his 1959 book Experiencing Architecture, Steen Eiler Rasmussen (1898-1990) reminds us of architecture’s way of translating ideas into space and how the end result—the intellectual and intuitive experience—makes us grasp something of the “essential nature or meaning of something.” From a feeling for place to an interpretation of function; from light, color, shape, scale, texture, rhythm, smell and sound to the metaphysical idea of being, buildings become architecture when one engages with them.

Yet, at times, our first experiences with architecture are accompanied by an initial sense of disappointment. Our visual recollections, or better stated, our visual interpretations from our years in architecture school become fictionalized. When visiting a famous edifice, how often have I found its scale to be misleading, the pristine images of a façade changed by the weathering and aging of materials, or the spatial sequencing different than the slides, PowerPoints, Google pages, or the glossy monographs published by Phaidon or Taschen. While today’s over scaled coffee table books serve an important purpose, they tend to promote architecture as an object, rather than an event that encompasses more than a visual experience. But let us be honest, there is nothing that can replace an in-person visit, and having a dependable visual introduction remains key to our first appreciation of any masterpiece.

The Schröder House

With a classmate in architecture school, I remember visiting the 1924 Schröder House in Utrecht, the Netherlands, designed by Dutch architect Gerrit Rietveld (1988-1964). My friend’s parents owned a Rietveld house in Maastricht, and together we researched the architect’s avant-garde approach to design. Despite carefully studying the site strategy, the floor plans, sections and elevations, and the important influence of the design principles of the de Stijl art movement on the overall composition of the house, I was disheartened when I arrived.

After walking along the tree-lined Prins Hendriklaan, through a typical Dutch middle class neighborhood, I discovered the house exactly where I had expected it to be, but the epiphany of finally seeing in-person this famous building was interrupted, as it now faced a four-lane overpass. What I saw as an intrusion to the sanctity of Rietveld’s oeuvre made me realize that architecture and its context live beyond the architect’s intentions.Image 1: Google images -Undated photographs of the Schröder House focusing on the object rather than the context

Caplutta Sogn Benedetg

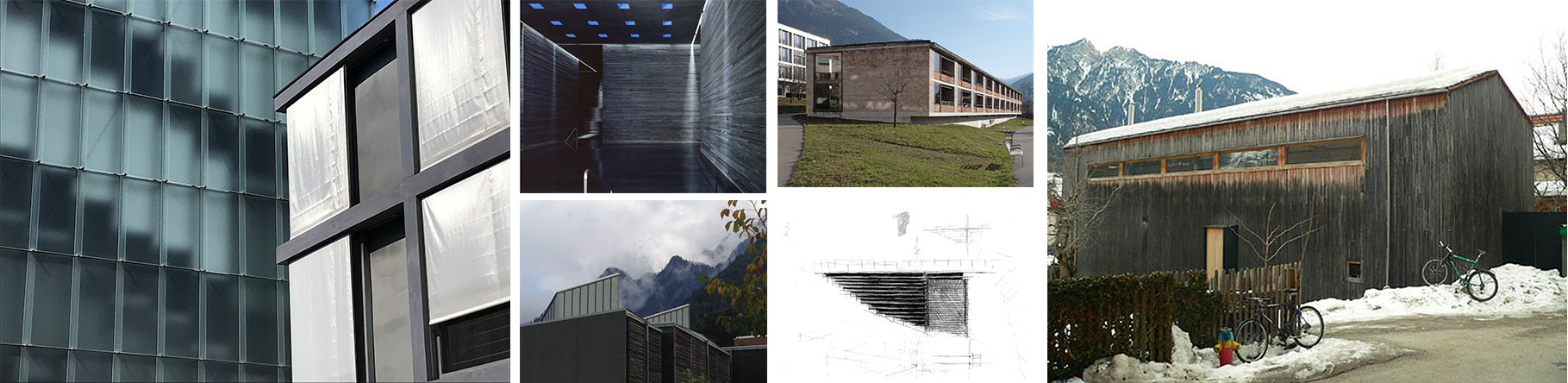

At times, the combination of epiphany and slight disappointment enables one to balance surprise and affirmation. This was never more true than during my first visit to the Caplutta Sogn Benedetg near Sumvtig, Switzerland (1985-1988), designed by 2009 Pritzker Laureate Peter Zumthor (1943-). While the best-known of his approximately thirty built projects remains the Thermal Spa (1996) located in the Alpine village of Vals—also famously known for the water of the same name—my favorite masterpiece of his is this chapel.

The chapel at Vitg had already received worldwide praise and I was eager to experience it in person. Following a pilgrimage to Zumthor’s nearby buildings (the word nearby may seem an oxymoron for most Americans but distances within Europe and in Switzerland are short driving distances), I was unaware of the magic that was to unfold.

The landscape, form and meaning

Set within the landscape, the chapel was modest in scale; a jewel. Situated on a steep slope in the hamlet of Vitg above the village of Sumvtig, the chapel is oriented to the East and parallels the expansive and sublime valley between the cities of Disentis (with its Benedictine monastery founded in 720) and Chur (capital of the canton of Grisons). The approach through a curved footpath offered a gradual change in scale while viewing the chapel—first, its shape, and finally, the beautifully crafted entrance details—giving me pause as to why such a simple gesture was enough to awaken my senses.

Was it the similarity in scale with the earlier chapel at the entrance of Vitg, or a consequence of multiple metaphors for the chapel: a teardrop, a roof echoing the form of a leaf or the hull of a boat, a soaring tower, Noah’s ark, or because of its unusual form, a spaceship, or worse, a giant hot tub. Perhaps it was due to the scale and how the architect’s unconditional attention to detailing offered an entrance to his past as a master cabinetmaker, a tradition transmitted from father to son.

Whatever the reasons, the chapel exhorted a profound and majestic presence, an experience that Zumthor defines for his architecture in general as being “…like a gap in the flow of history, where all of [a] sudden it is not past and not future.” Ever since being introduced to Zumthor’s work, I have felt this magic throughout his buildings and attribute my impressions to his ability to create an architecture of permanence that approximates both a way of making a place as well as a way of demonstrating how materials refer to ancestral modes of building. “…It’s about space and material,” Zumthor said at his Pritzker inaugural speech when he defined architecture. In today’s architectural climate, both in academia and in the profession, such simplicity of thought is refreshing.

The history of the project

The genesis of the project in Vitg traces its origins to a national competition which reflected the congregation’s desire to replace a 13th century chapel destroyed in an avalanche in the mid-eighties. Despite the decision to relocate the chapel to a nearby site in order to protect it from further natural disasters, the new religious structure respected the austere and compact volumes of the white churches punctuating the valley’s landscape. Ultimately this may be the only resemblance that Caplutta Sogn Benedetg has with the original chapel.

The process of aging

Constructed primarily of wood—a vernacular material used for the region’s houses, farm houses, and agricultural buildings—the Caplutta Sogn Benedetg adopts this custom in opposition to the traditional noble materials employed for religious structures. Beyond this fundamental change in how to clothe a building type (i.e., church), Zumthor’s choice of wood enables the architecture to come alive due to the weathering of material.

The images below show how the exterior surface is at times charred by the sun, rendering the shingles gold, brown, and punctually black, then transitioning to the north face where the wood maintains its youthfulness, as if it was the day of the chapel’s dedication. While buildings display the effect of climatic conditions, the chapel’s beauty is a result of its ability to embrace weathering, and as a result it gives a new sense of how one may want to read a building.

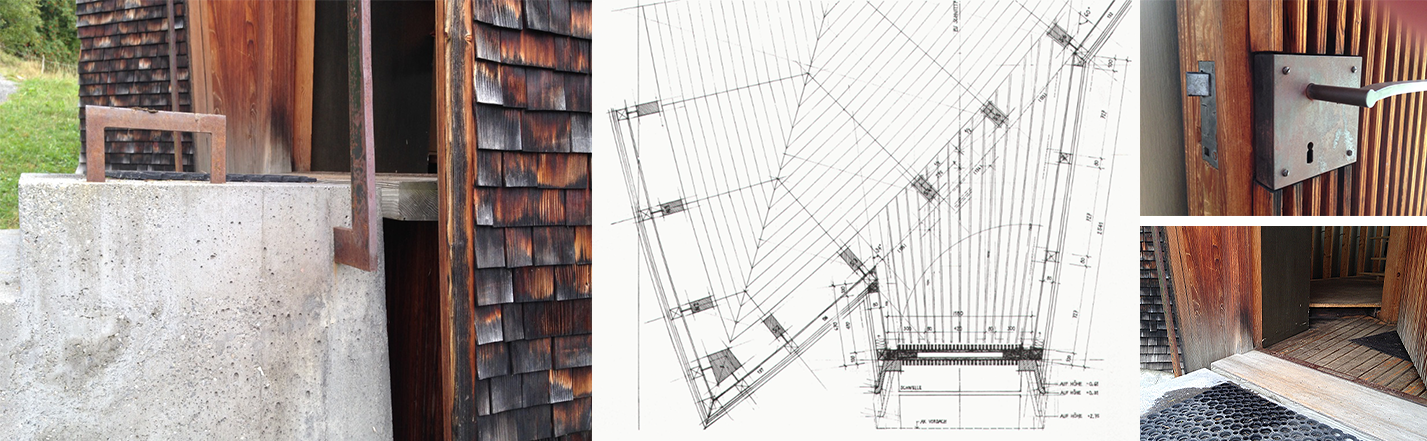

Image 7: Details of the aging of the chapel’s shingles from the sun blackened surfaces, to the north untouched surface by direct light (author’s collection)

Image 7: Details of the aging of the chapel’s shingles from the sun blackened surfaces, to the north untouched surface by direct light (author’s collection)

From the exterior, if stripped of the bell structure and discrete cross on the roof, one would not know the building’s function. However, upon entering, one is immediately confronted with a space that could only be called sacred. The beauty of this single, all-encompassing room is found bathing in light, with shadows cast by the wooden structures on the curved silver wall. The visual density and repetitiveness of the tall wooden membranes reminded me of an organ pipe and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s quote that “Music is liquid architecture; Architecture is frozen music.” There is a Benedictine sense of austerity and solitude present in this chapel, and Zumthor’s detailing reflect the sense that “God is in the detail.”

Image 9: Google images and author’s collection: details

Conclusion

While each of Zumthor’s projects is unique in their own right, the curved plan of the chapel stands out among his masterpieces. Zumthor describes the chapel as “a building [which] develops from a leaf or drop-shaped plan.”

In the language of mathematics and geometry, the basic form of the church is half of a lemniscate, but none of my research forays into the multiple essays on the chapel’s description, elaborate on this shape or attempt to clarify how one builds a lemniscate. This project remains seminal for me, and is an example of how poetry and place can achieve harmony. At the same time, the project left me with questions about the shape of the building. Committed to understanding this, I decided to now embark on a discovery for answers to the following questions:

What is the nature of this form, which looks like a leaf?

How might one approach the question of representation of this geometry?

To what extent can this form be associated with a circle, a hyperbolic curve, or an ellipse?To what extent does this geometry depend on historical precedence?

Image 10: Google images -Roof and plan of the chapel

Image 10: Google images -Roof and plan of the chapel

Architectural Education: Peter Zumthor Part 2 -the lemniscate