Thoughts on architectural education, Part 1. While studying architecture in Switzerland, I remember struggling with the many competing and conflicting voices regarding what architecture meant, and most importantly, what my future role as an architect might hold.

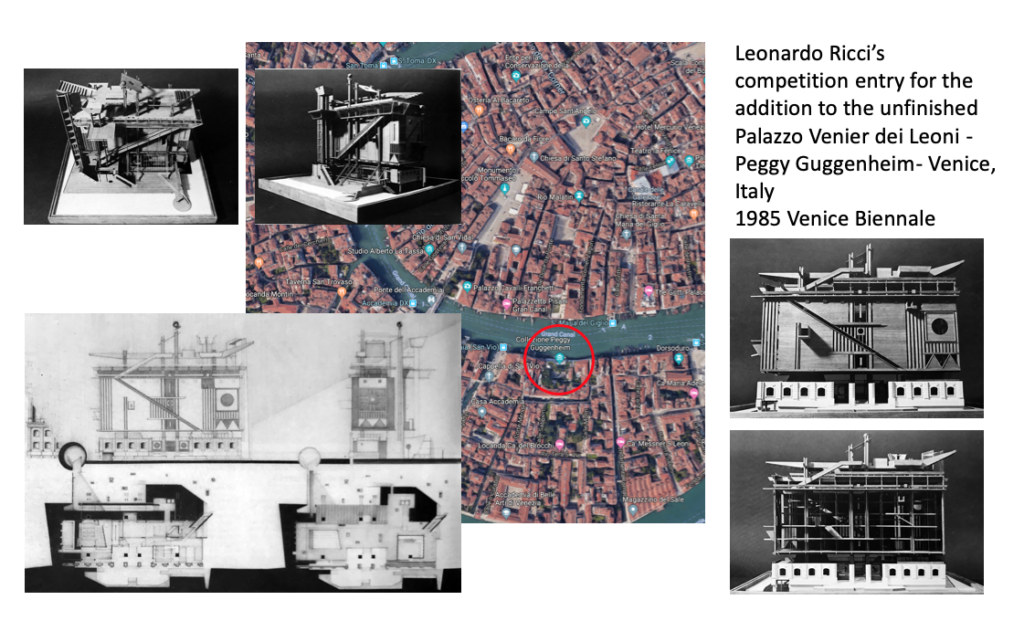

A few years later, I met Leonardo Ricci (1918-1995), an Italian architect and Dean Emeritus of the School of Architecture in Florence, Italy. He was a master in the traditional sense of the word, and for me as a young faculty member in the US, he embodied what I came to learn to be an existential truth about the art of making architecture.

But above all, he was, and will always remain an inspiring educator for me as well as for generations of his students. His demeanor was humble, yet he was the author of an architecture that could only be described as visionary. While our interaction was brief as colleagues at the University of Kentucky, he left an indelible mark on my way of thinking; one that gave meaning to the trilogy between the need to create a model of life, give it structure, and then allow shape to take place.

Ever since then, my commitment to this way of thinking nurtured my way of living, my practice of architecture and, most importantly, my commitment to a new generation of architects through various academic responsibilities.

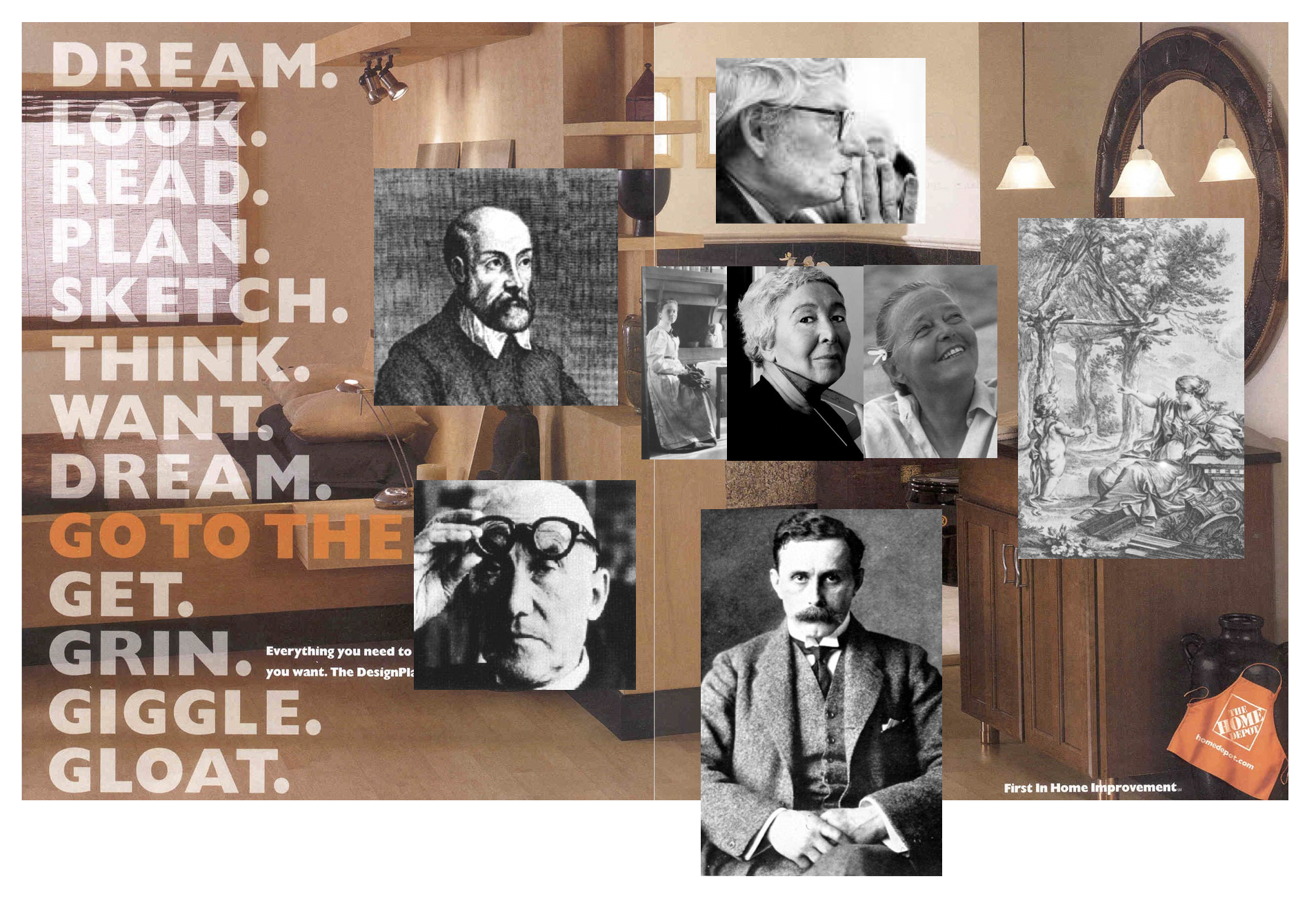

One day, I stumbled on a double page advertisement (Image 2, above) by a big box hardware store that stated that they could provide most of the services that I was trained to do: dream, look, read, plan, sketch, think, want and dream (again). From the idea of design (from the Italian verb designare, which means to draw) to one of a project (a notion of projecting an idea into the future), I realized that perhaps the value that I was expected to bring to my art was now similar or simply reduced to a consumable product.

What purpose did I now have when the public could practice architecture without a license, or worse without the added value of an architect? One needs to drop by one of these hardware stores or IKEA on a Saturday morning to witness hordes of neophytes selecting a cornucopia of materials or furniture with the desire to implement their architectural dreams.

Master architects

I thought of the master architects whose work I learned from and admired (Image 3, above). They were part of the history of both our discipline and our profession, but now may have no further refuge in the next generation if our art is no longer needed. But perhaps I missed something essential between an Architecture created by the masters with a capital A, and architecture that was superbly, yet simply designed by anonymous architects.

A further thought came to mind. Have those architects not already been replaced by many similar 21st century stores and in particular TV home remodeling programs with signature contractors promoting a do-it-yourself strategy? Clients, in their most honorable roles as Medici patrons, are now morphed into demanding customers, and since a decade have played the role of avid consumers of TV shows (Image 4, below).

From Hallmark TV family series to The Simpsons, from sitcoms to the Kardashians (with PG13 labeling!), we look at these shows as if we are looking into a mirror and witnessing ourselves. Similarly, today our houses and the renovation of our homes have become center stage in all possible medias (i.e., HGTV, web announcements, Instagram posts), and this in 24 hours round the clock at home, at our office, at the gym, and in airport lounges!

I remember reruns of the original 1979 TV series This Old House with knowledgeable Bob Villa. As a young architect, the series’ content seemed informative about issues of preservation, and tangible as a way to learn essential tricks of the trade, especially those used in the United States as that was also foreign to me. Yet this show held a certain pragmatism as construction often needs to be.

Eventually, this program morphed into new formats such as Design on a Dime, Extreme Makeover, Fixer Upper, Rehab Addict, and Buy Me, mostly hosted by HGTV. While their purpose is varied, viewers are entertained and receive an identical blunt message: local designers and contractors now provide architectural services and the journey to completing your dream house is exciting, rewarding, and, of course, promoted as a less expensive endeavor.

Democratization of design

While I believe that the democratization of our built environment is welcome — as it has exponentially increased the public’s interest and appetite for design issues — why is it that the quality of current built surroundings remains visually identical; mostly poor, uninteresting, and often devoid of simple yet progressive ideas about a model of life?

Perhaps we have already reached another milestone in our digital age; a virtual space where we no longer need particular buildings and places to accommodate some of our essential human needs (Image 5, above). Case in point:

- From traditional brick and mortar mom-and-pop stores, to flagship and big-box-retailers (i.e., Walmart and Cosco), now Amazon’s online shopping provides us with next day delivery of millions of items that cover most of our basics -from groceries to leisure items.

- To compete, local bookstores are on-line and electronic readers have competed to replace physical books.

- We broadcast our social interactions without any further need to interact in a public space. We Tweet, Kik, Message, Snapchat, WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram, our thoughts in 280 characters or less, and Google the web without ever needing to travel, communicate or interact physically.

- Let alone that AI is creeping into our daily lives…

The architecture of…

Our social skills are disappearing behind expensive portable and addictive screens (with the event new googling gestures) made in emerging countries. I sometimes wonder if our traditions have expirations dates? This new virtual space is a natural evolution of our physical world and, let’s be realistic, we can no longer live without those man-made digital prosthetics. The complex implications are far beyond this short commentary, and academic literature and popular web sites extensively cover a variety of attitudes and remedies aimed at adjusting our new ways of living on a highly connected planet.

Yet, in this constantly and rapidly evolving world, one where digitalization imposes and bends our needs while saturating us with information that can never be processed intelligently, the word architecture has happily returned to its anthological meaning. In countless news articles, editorials, and advertisements, architecture has subtlety reintegrated itself in our daily lives.

In a certain way, I am comforted by its abundant use: i.e., the architecture of the brain; the architecture of the electrical car; a strategic architecture of warfare; the architecture of healthcare; a new security architecture for East Asia; the architecture of the Kyoto Protocol (on climate change); … architect of mass human rights abuses at the border; and, “America led the world in constructing an architecture to keep the peace” (President Obama’s 2009 Nobel Peace Acceptance Remarks), Image 6, above.

These examples no longer suggest the architect’s métier is solely providing buildings, or more correctly a work-of-architecture. But as a noun, in those daily uses, architecture reflects back to its original meaning. Its Greek origins remind us that architecture is the combination of two leadership roles: ἀρχι- “chief” and τέκτων “creator”. The connection of those words legitimizes our art form, but perhaps most essentially, we can now envision a renewed interconnectivity of our social and public roles to provide a model of life, and through this to regain our role as architects beyond the mere making of art-buildings.

Perhaps the true locus of those changes may be found in academia, not simply in architectural programs but in a learning environment that favors a true interdisciplinary approach to problem solving. As architecture regains its letters of noblesse, we may want to think about:

The RESPONSIBILITY of architecture in the first quarter of 2021?

What does it mean to provide LEADERSHIP in architecture in the first quarter of 2021?

What does INNOVATION in architecture mean in the first quarter of 2021?

Additional blogs of interests

Thoughts on architectural education. Part 2

Some thoughts on teaching. Part 1

Some thoughts on teaching. Part 2