Design versus project. There is much to say about how curricula are developed and their importance in defining the content of any rigorous academic program; in our case an architectural education. Traditionally, classes within the discipline of architecture are taught according to required and elective professional courses, while additional opportunities provide students with a personalized liberal-arts education.

“The mentor teacher…shows us his subject and then ourselves. The mentor magician shows us his world, and then our possibilities. He makes the world’s contradictions look like connections, hidden to lesser eyes.”

Adam Gopnik in At the Strangers’ Gate: Arrivals in New York, p.129

The sequencing of all courses is defined by each institution, yet follow national regulatory requirements (the National Architecture Accrediting Board (NAAB) serves as the official external reviewer of all professional architecture programs in the USA). The NAAB defines a minimum of conditions to guarantee that students are taught a prerequisite content based on an understanding or ability of specific subject matters. However, this accreditation process leaves ample room to legitimize the institution’s curricular ambitions in how to implement a professional degree (i.e., a bachelor or master of architecture).

Pedagogy and didactic

And yet for educators, regardless of regulatory requirements, the focus on issues of pedagogy (the theory of education) and didactic (the theory of teaching) have always been paramount in defining the identity of their program and experiences offered to their students. Furthermore, teaching the discipline of architecture, versus the learning of how to become an architect, has been, since two centuries, the center of passionate debate regarding how best to mentor the students. To implement these professed and often unnecessary opposites, is to differentiate teaching and learning as two contrasting pedagogical models.

Teaching and learning

While one model favors a master-student relationship that imparts fundamentals and required subject-matters (teaching objectives), the other model entrusts students to assume responsibility of their learning through a deeper introspection (learning objectives). While I believe that there is no perfect educational model, I favor both approaches in order to bring a balance between the best of both worlds.

To impart and communicate knowledge (teaching) and the discovery and the apprenticeship of knowledge (learning) should work in tandem. For me, fundamentals are what teaching should impart and the creation of ‘new’ knowledge is what learning should offer. But what does this mean and are they always in direct contradiction?

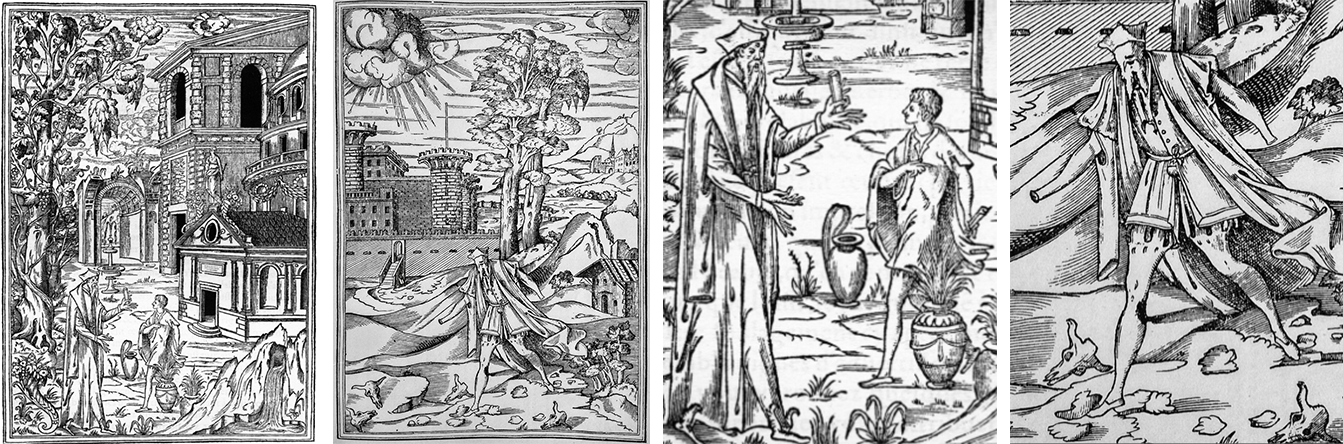

Before suggesting an explanation, I was reminded of two famous woodcuts by French architect Philibert de l’Orme (1514-1570). Recognized within an influential book for the history and theory of architecture, whose content includes a number of geometrical, technical and theoretical concerns, de l’Orme concludes his treatise, not with architecture but with images of two architects: the good and the bad architect. While published in 1567, the iconographical power of these images remains relevant today. Their ability to embody two academic paradigms represented by knowledge and education, or the lack of, gives us much pause. Between the good architect (images 1 and 3) and the bad architect (images 2 and 4), each representation suggests an allegorical message about the profession (Image 1, above).

- (Images 1 and 3) Within an idyllic urbanscape divided between nature (the natural) and culture (the man-made), the good architect is depicted as a scholar whose interaction with a novice suggests the transmission of knowledge. He has three eyes, four hands, and winged feet. These symbols, with a scroll in one of his left hands, display the master’s multiple abilities and virtue at the service of education.

- (Images 2 and 4) The bad architect seems lost in a desolate landscape outside of a medieval fortified town scattered with skulls. He has no ears, no eyes and no hands, thus lacking the ability to learn, to see or to work.

Design and project

I suggest that to clarify what I believe to be a fundamental duality between teaching and learning architecture may lie in a contemporary approach of the notions of design and project: (faculty) teach design and (students) learn to project.

- DESIGN (from the Italian word designare) suggests several meanings beyond the simple understanding of an act of drawing. On the one hand, we understand design (1) as a plan leading to the construction of a building or a work of architecture. This encompasses an accepted system of drawing codifications that enable architects to represent their ideas which allow contractors to physically build what is described in the architects’ drawings. On the other hand, design is understood (2) as a sequencing or staging of events.

Finally, (3) “to design signifies a process of developing a design,” an apprenticeship of translating ideas into space. While this approach to the notion of design is closest to my love for teaching, as an educator, and in particular as the program in architecture where I teach is sanctioned with a professional degree, all three approaches to design are seen as fundamentals that need to be imparted to students.

And yet, in this process of transmission and inheritance between teaching and learning, I often wonder how fundamentals are instructed today as it seems that they are being lost from generation to generation. Colleagues retire after a lifetime’s commitment to academia, and with their departure most often their knowledge and experience is never duplicated. Junior faculty arrive with their own autobiographies and educational aspirations, which are always welcome and so needed for academia to recalibrate its identity and contemporary mission.

But, in this generational conundrum, one might understand that to impart fundamentals is no longer possible in a traditional manner (i.e., a constant return to the core of our discipline). In this new reality, fundamentals may now be seen as a result of a dynamic process that reflects the students’ learning abilities in order to interconnect between existing knowledge. This is where the notion of project takes on new meaning.

- Similar to the above description, the word PROJECT has various implications. From its Latin origin projectum, signifying “before an action” it shares the idea of planning something or being a plan; similar to the first definition of the word design. For example, in a university setting, a project is typically understood as a research assignment that students work on by establishing a hypothesis, which is followed by research and a report in various shapes and forms.

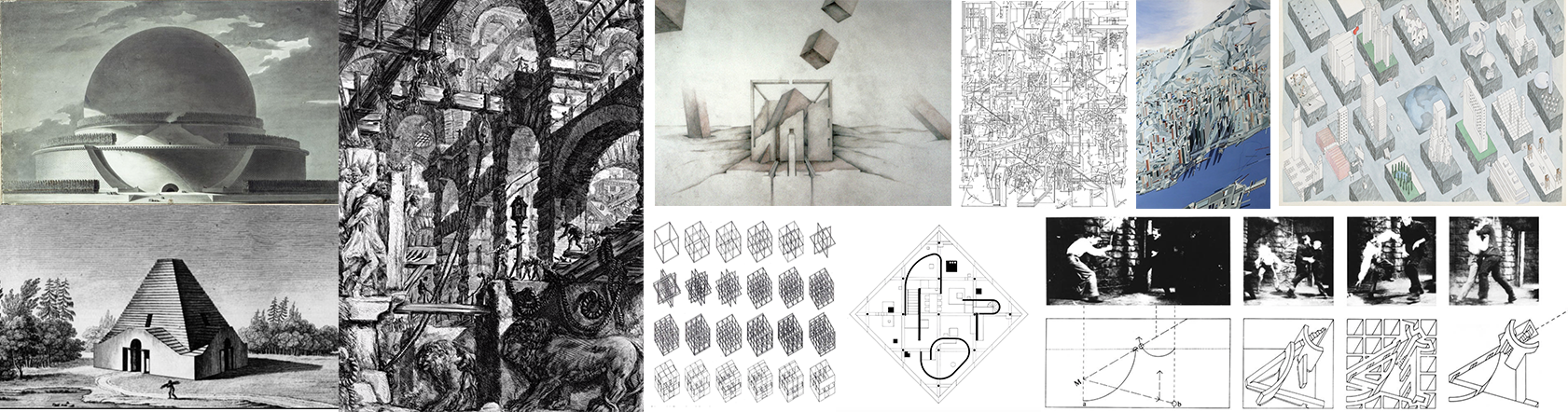

However, in the world of architecture, this definition offers other important interpretations, in particular about what may constitute Architecture as either a built artifact or a drawing (unbuilt); the latter being exhibited by 18th century projects of Boullée, Ledoux, and Piranesi, and closer to us through the early architectural iconographies of Raimund Abraham, Peter Eisenman, John Hejduk, Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind, Rem Koolhaas, and Bernard Tschumi (Image 2, above).

Here, project as a verb is about projecting in the future, pushing the disciplinary boundaries to lay down new grounds of space making. Often reversing the codification of conventional drawing techniques, the meaning of designare is now in favor of form. Form as an idea and not a shape.

To further this idea of projecting, is to establish among students opportunities and an appetite to creatively seek new knowledge. This is more relevant than ever. In a world where students have constant access to digital information at the click of a finger, it is the faculty’s responsibility to guide them to seek out a personal interconnectivity between existing knowledge, one that leads to the creation of new knowledge.

To achieve excellence in this approach to the idea of a project, students will either interpret existing and obvious links between knowledge, or more promisingly create an interconnectivity between disparate ideas, something that relies primarily on their personal and autobiographical experiences. The coming together of unrelated, distinct or unlikely ideas is a fascinating locus by which the idea of creating new knowledge is possible and encouraged.

Image 3: Google Images – the good and bad government by Ambrogio Lorenzetti

Conclusion

In conclusion to the primacy I have set on the title of this blog design versus project, I am drawn to the world of painting and in particular to the three frescoes (1338-1339) exhibited in Siena’s Palazzo Publico, Italy. The allegorical frescoes are the creation of Italian International Gothic artist Ambrogio Lorenzetti (c. 1290 – 1348) and further de L’Orme’s allegorical imagery of the good and the bad architect. Here, the health of the city is admonished through the deeds of the Good Government (above image 1) and the Bad Government (above image 2).

This suggests that the role of architecture is no longer served by architects who create works of art, but instead by those who serve a higher calling which is civic in nature. This topic is covered in my blog.