Herzog et de Meuron Tavole House. Within the plethora of contemporary domestic houses, I continually return to study the Tavole House (Stone House) designed by Swiss architects and 2001 Pritzker Prize Laureates Jacques Herzog (1950-) and Pierre de Meuron (1950-)—the first Pritzker Prize given simultaneously to two architects.

The use of the word contemporary might be a misnomer for this house, as the project’s aesthetic does not support what I see today as new, a word that typically relies on boisterous or garrulous form making. And yet, the Tavole House is so very much of our time, so just and appropriate, despite its completion over four decades ago (1982-88). Why is this? Perhaps a first line of defense is to read the architect’s own comments about the intervention:

Tavole House

“Set in an undulating landscape of abandoned olive groves, the three-story house stands on a promontory, engaging part of a former stone terrace. The design concept of the house is based on the fusion of plan, elevation and section. The building is characterized by a cross, made visible in the construction of the side walls where the in-fill dry stonecomes in contact with the reinforced concrete frame.

The structure occupies the center on the “piano nobile,” while on the top floor spaces are more interconnected. Here, the house rises above the trees, giving a panoramic view through the vertically articulated strip windows. This notion of extension has its equivalent in the opposite direction with the raised terrace and its pergola-like enclosure. The external wall infills are of slate-like rubble stones, the window shutters are of steel sheets and the door and window linings are of split slate sheets. On the whole, the detailing is spare. Herzog & de Meuron, 1988[1].”

My interpretation

Image 1: Google image of the location of the Tavole House

Image 1: Google image of the location of the Tavole House

Located in Liguria, Italy, halfway between Nice(France) and Genova (Italy), Tavole is a small village of roughly 90 inhabitants. The house is located at its outskirts amidst an abandoned olive grove, and has a wonderfully discreet presence with both its small footprint on the landscape and the architects’ choices of specific local construction materials.

While the siting of the house exhibits essential attributes in what Italian architect Vittorio Gregotti (1927-2020) calls a principle of settlement—an understanding and interpretation of basic cultural site conditions such as the seasons, orientation, winds and rain, humidity, topography, soil and view to name but a few—my fascination with this project is how vernacular and indigenous traditions can coexist seamlessly with the idea of innovation; and this, by building on the great lessons of architecture. Most important for me, is how materials and structure are key in understanding the project.

Like many regional buildings around the world, houses, religious and agricultural edifices were constructed around the availability of local materials such as earth, wood and stone. Reflecting ancestral human gestures when working the landscape, farmers cleared the fields of brush and rocks to prepare them. Stone and wood were removed and first used as border walls to terrace or enclose pastures, and when shelter was necessary, the architects through instinct, observation and experience, erected walls that became enclosures enabling basic human activities to take place—the sheltering of farm animals, and the safeguard of provisions during the winter season.

Building techniques

Buildings were assembled using rudimentary techniques for stone and wood, and construction often expressed—particularly in the case of stone construction—a pattern that was laid free-hand, generally with no mortar. Human measurements were favored over predetermined plans, and the overall geometries of buildings remained simple with structures based on a static system of compression. Despite what might be understood today as a set of restrictions, the resulting architecture had tremendous “expressive, plastic and symbolic values.”

My fascination with the Tavole House reflects similar admiration for what vernacular architecture represents: ancestral building techniques, usage of local materials and know-how in craftsmanship and building skills. Yet, this humble stone house offers another important reading based on an elaborate and subtle interpretation of the history and theory of architecture. Three observations are, in order:

1. “The building is characterized by a cross…”

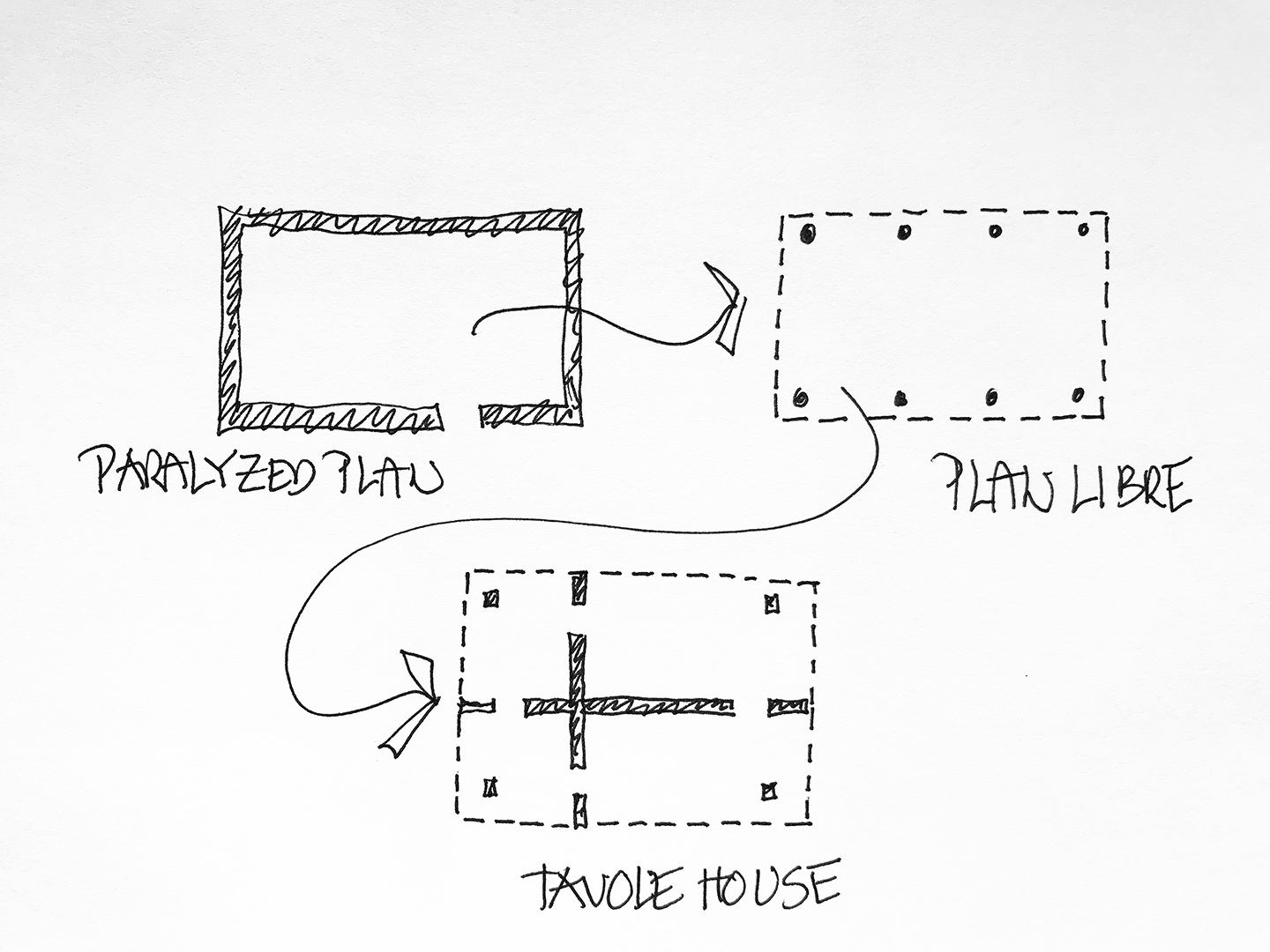

Ever since the creation of the plan libre (free plan) by Swiss architect Le Corbusier (1887-1965), load-bearing walls were slowly abandoned in favor of a structural system using individual columns with beams, slabs, arches, vaults and domes. This strategy enabled rooms to become open spaces with new spatial relationships between areas and functional requirements. The new-found freedom of the free plan allowed floors to express different spatial organizations from level to level, and create skins of buildings almost entirely fabricated from glass.

And yet within this modern language, the Tavole House re-questions the belief that the open plan is the only contemporary way to organize spatial complexity, thus the architects designed the house by interpreting traditional precepts such as the wall, a structural system that Le Corbusier fought so vehemently against; something he called a paralyzed plan that was organized by a series of rooms defined primarily by walls.

The following three diagrams illustrate the conceptual interpretation of the Tavole House as the intersection of the paralyzed plan (walls) and the free plan (columns).

Here, the plan of the Tavole House (Image 2 above that features the piano nobile -one of three floors) recaptures the convention of load bearing walls and uses the intersection of two walls at right angles, made out of reinforced concrete, to organize four distinct rooms connected to each other through a peripheral circulation path. This strategy of movement is similar to a classical enfilade where a “corridor” connects rooms one to another along the interior facade. The hierarchy of each room is well defined with the master bedroom (1) and bathroom (2) tucked on the north side at the back of the house, while the living room (3) and kitchen (4) extend to the south patio space, allowing light and passage between the interior and exterior.

Furthermore, what is fascinating for me in a second stage of the analysis of the structure of the house, is how the architects extend the cruciform interior walls by registering piers and “hidden” square columns at the periphery of the façade (below image).

2. “…made visible in the construction of the side wall…”

Two types of support are found at the periphery of the house. First, four piers define the passageways between the edge of the cruciform structure and the exterior envelope. They “belong” semantically to the wall as their form is aligned with the interior cruciform structure while also being expressed in the façade as a post and lintel frame structure. Four additional square columns are strategically placed at the corners of the rectangular floor plan, but are “hidden” by the skin of the building, both in the façade and from each of the four rooms. The walls, piers and columns recapture, in a subtle manner, the historical evolution from a masonry load bearing wall to a columnar system (last diagram of the blog), the latter which ironically becomes absent in its tectonic expression throughout the building (to the exception of the pergola).

Like many modern and contemporary houses, Herzog et de Meuron’s Tavole House is heir to the origins of architecture as expressed in the primitive hut (1773) and theorized by L’Abbé Marc-Antoine Laugier (1713-1769)—as both the foundation of an abstract skeletal structural system and the idea of a shelter through the “anthropological relationship between man and the natural environment.” (above image)

3. “…where the in-fill dry stone comes in contact with the reinforced concrete frame…”

At last, the acceptance and reversal of traditional construction methods is found in the architects’ expression of the in-fill. The skeletal framework is ready to receive a non-load bearing skin (above image enclosure expressed in green), yet its expression is one of stone, a material used traditionally throughout the region and in the world as a load bearing wall system.

Conclusion

Contrary to the accepted modern free plan, the Tavole House is a refreshing interpretation of the origins of the primitive hut, and extends its conceptual language by giving it a necessary solid skin that offer the inhabitants protection from the outside environment. While the theoretical concept makes sense, the usage of stone as a skin creates a conscious visual ambiguity of what is load bearing with what is infill. When viewed frontally, any of the house’s facades (the infill), despite their sense of weight, express an abstract pictorial plane that at moments gives the illusion of being able to slide between the horizontal beams (below image 6).

The Tavole House reminds me of another wonderfully executed intervention by Herzog et de Meuron, namely the subsequent project for the Domino Winery in Napa Valley, CA (1997). The return to using a load bearing wall system for this building follows the architects’ quest to respond to the question of what new spatial condition can a contemporary architecture offer, when historically buildings have moved from structural wall systems to columns with endless possibilities offered through the notion of the free plan.

At the Domino Winery the skin of the wall is rethought as a traditional mass, this time constructed out of gabions—an engineering technique to build retaining walls for roads and rivers—rather than dry stone as in the Tavole House. This invention allows the thickness of the wall, which generally is opaque beyond necessary window and door openings, to show transparency by letting light filter through its thickness (see below images). The impression of an exterior mass takes on a new meaning when seen frontally, thus enabling the thick masonry to become a skin of stones; a poetic gesture expressed through material and structure.

Image 9: Google images -non-load bearing skin of the Dominus vinery

Epilogue

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was considered one of the greatest contemporary composers who had a “reputation as a musical revolutionary who pushed the boundaries of musical design.” His chief conceptual ideas were presented in the celebrated book Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons, a wonderfully provocative series of essays delivered at Harvard in 1939.

Reviewing my copy of the book, I was reminded of the importance of poetry—derived from the Ancient Greek word ποίησις (poiesis)—as a way to evoke meaning; an “activity in which a person brings something into being that did not exist before.” Stravinsky set the stage of his lectures by mentioning that poetics was embraced by classical philosophers, not as lyrical dissertations, but more through “the single word techné [that] embraced both the fine arts and the useful arts and was applied to the knowledge and study of the certain and inevitable rules of the craft.” He further writes “That is why Aristotle’s Poetics constantly suggest ideas regarding personal work, arrangement of material, and structure.”

For me, Stravinsky’s attitude toward the poetry of making music is very similar to the crafting of architecture. His stance reflects a reverence to tradition as not a blindfolded attitude to a bygone past, but something that is truly revolutionary. In this sense, and quoting Stravinsky again when he refers to G. K. Chesterton (a famous British mystery writer): “…whereupon Chesterton pointed out to him that a revolution, in the true sense of the word, was the movement of an object in motion that described a closed curve, and thus always returning to the point from where it had started…”

Image 10: Structural evolution-revolution from the wall to the column (author’s drawing)

To me, both the Tavole House and the Dominus Winery demonstrate Herzog et de Meuron’s ability to create poetry through material and structure. However, their revolutionary impact may be the reversal of the historical chronology of wall to column seen in these two projects: wall becomes skin (Tavole), and wall then becomes transparent (Dominus).

Additional blogs on the topic of vernacular architecture

Ballenberg: a vernacular architecture museum

Architecture Education: lessons from vernacular architecture—invention versus re-inventing

Case Rezzonico by Livio Vacchini, Switzerland

Street Pavement: Wittenberg, Germany

A question of preservation

[1] https://www.herzogdemeuron.com/index/projects/complete-works/001-025/017-stone-house.html