Inventing versus re-inventing. In past blogs, I stated that my academic and professional interest favors re-invention over invention. Working in the creative field of architecture surrounded by colleagues and students who thrive on furthering their art form, I always find it curious when reviewing student work, how many of them claim to invent a site strategy, to organize domesticity, or state a position in architecture that wants to be new.

“The distinguishing feature of great beauty is that it should surprise to an indifferent degree, which continuing, and then augmenting, is finally changed to wonder and admiration.”

Montesquieu (1689-1755)

And this, often for the sole purpose of being new at the expense of any other worthy criteria. Perhaps students don’t state it as forcefully as this, but I see in their intentions the result of the constant pressure to create something that has not yet been seen.

Question of the new

For a beginner this stance is normal, but if the sole purpose of a design is to be new, this attitude may hinder the success of the project. Add to this conviction about newness a healthy dose of youthful stubbornness, and you have a perfect recipe for a design project that has little backbone or subtle complexity. This is because of the students’ belief that creating something ex cathedra is what gives architecture its legitimacy.

To be innovative, cutting edge or even avant-garde, seems to be the credo of many students, often without much reference to what these terms truly mean. Call it a position of self-certainty, where ideas only follow design decisions of the new and end up being often erroneous and having little to do with the calling of a project. Yes, the nature of being of a project should be more important than the “artist’s” individual imposition on the project.

Question of the “I”

When listening to students, I often hear statements such as I want, or because I like it, rarely do they say that their design strategy is in response to [something]. In this process, students voluntarily disregard any sympathy to a context, a memory of a site, an interpretation of indigenous building techniques, or a genuine interpretation of a program’s brief to name but a few possible design strategies.

Giving birth to an idea should never be a solitary or exclusive process: it is a discussion among many constraints—real or self-imposed—that create a healthy tension that promotes excellence in its final resolution. And yet, many student’s adopt a self-reflective position determined by their willpower as the only way to design. They are taught early on that they must invent in order to create and legitimize ideas and thus show that they are worthy of being labeled a talented designer.

Where this stance comes from may have multiple origins. One that I repeatedly point towards is that during a typical first-year cursus in most architecture programs in the US, students are trained as artists/designers and not as architects—mainly because of the idea that an undergraduate degree is as much about receiving a solid liberal arts education as it is about learning about architecture. Perhaps liberal arts outmaneuver architecture because they are intended as a looser course of study than a professional degree that requires discipline to understand the complexity and profundity of the art of making architecture.

Consequently, and specifically for me, second year students often have difficulties understanding how to negotiate concessions that are the hallmark of orchestrating any work of architecture. (This obstacle remains with some students through their subsequent years.) While a design gesture will always remain critical to offering clarity, intention, and to a certain degree a strong formal design proposition, the complexity of architecture goes far beyond the unique imaginative stance of the author; i.e. inventing, which in academia is often about form making.

Finden and erfinden

I have always appreciated the German words finden and erfinden. While both are based on the word finden, their meanings differ radically: one is to find, and the other is to discover. I favor the latter (erfinden), as to discover is a process that leads to the rediscovery of something existing through a critical eye, and becomes integral to re-invention; i.e., being part of a certain context, a lineage, or memory that is uncovered and reframed in a different way. I have always had difficulties understanding how in architecture one can claim to invent from nothing, perhaps because the palimpsest of knowledge is so ever present as culture partakes in a continuity between past and future.

This attitude might seem passé, especially in light of what academic circles promote as non-referential architecture—for me, an oxymoron in terms of an architectural identity—but given my own training, practice, and teaching, reassessing the past and being influenced by it is healthy and gives the author of any design project the capacity to own their judgment; one that makes common sense and lends beauty to the poetry of space making. Too often in architecture schools dogma is used to legitimize architecture, while for the end user, who buildings serve, there are far too many subtle autobiographical attributes that influence the enjoyment of space and place that do not retrace or read the architect’s mind.

School of Cugy, Switzerland

Image 1: Cycle d’Orientation de Cugy, Classroom building to the right and library to the left (author’s collection)

During a trip back home to Switzerland, a friend recommended that I visit a recently completed secondary school in Cugy, located in the canton of Fribourg. The images he shared with me were tempting, as I had not seen much recent architecture in the French speaking region; especially those in my home canton.

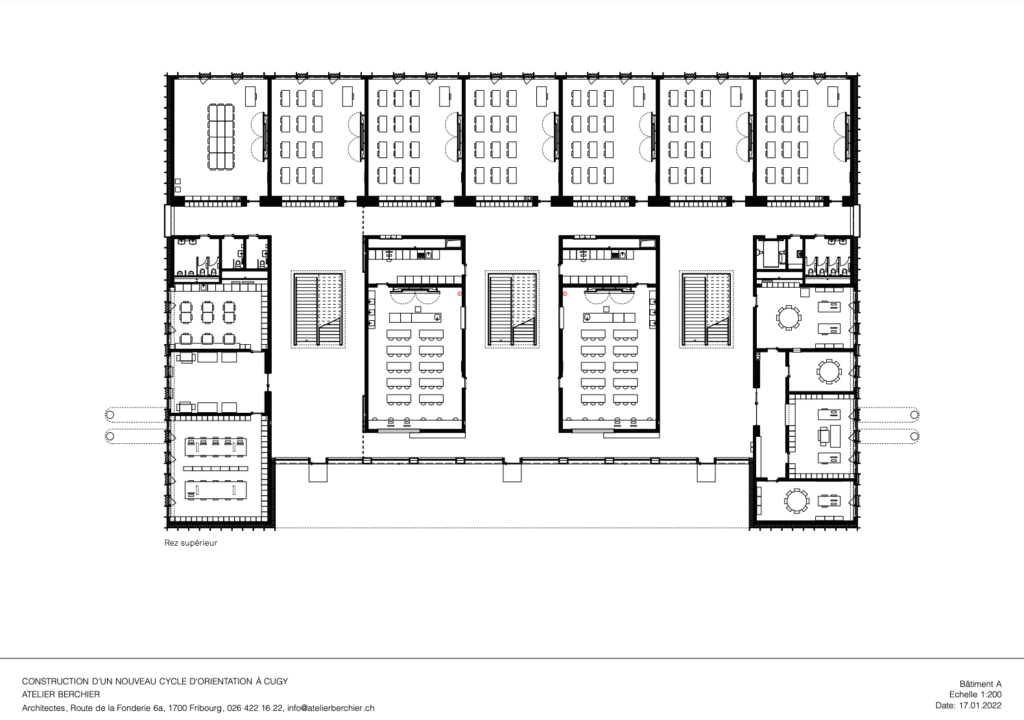

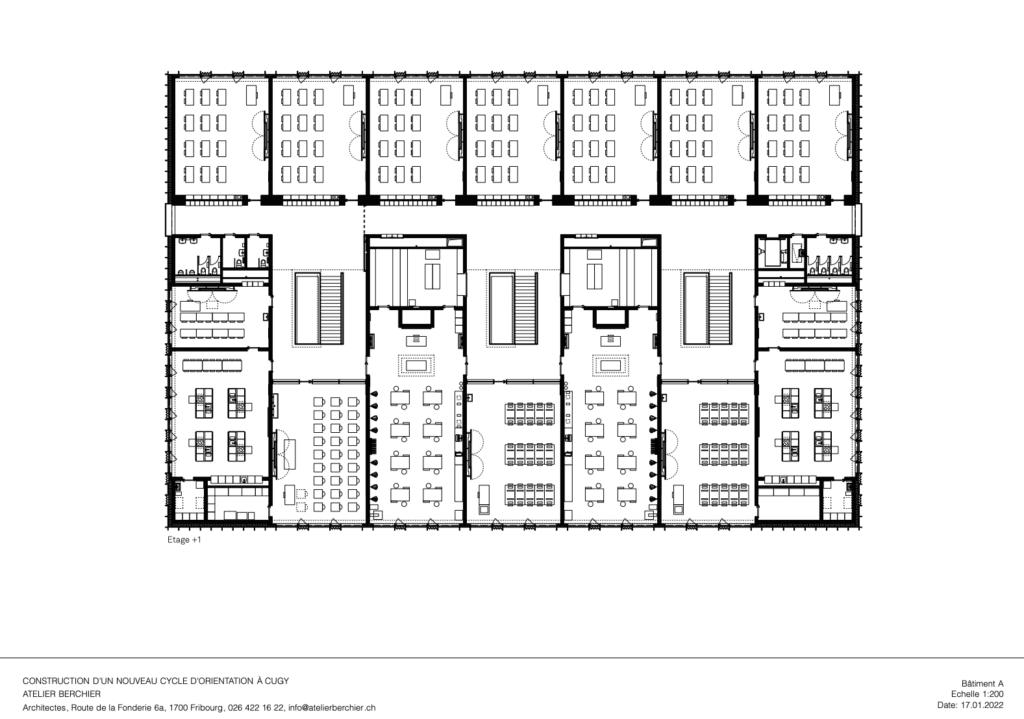

The school complex resulted from an architecture competition—customary throughout Switzerland for any public building—and was created to respond to a demographic growth of students within the region. Situated strategically between neighboring villages of Fétigny, Montagny, and more distant enclaves of the canton of Fribourg, the recently opened school of Cugy (2019-2021) currently serves 400 students, but is designed to expand to a capacity of 500.

It was cloudy the day of my visit, but fortunately classes were in session. Situated south of the main village road, the school complex designed by ATELIER BERCHIER (Fribourg) is formed by three two-story buildings (Image 2, above) comprising 1) twenty-one classrooms with administrative offices; 2) a library, dining facility, and specialized teaching rooms; and 3) double gymnasium courts with locker rooms and heating system.

The buildings were easily recognizable as their scale differed from the nearby individual villas, yet they offered a human scale in a building type that could have easily overwhelmed the site and the nearby village. No pronounced pitched roofs mimicking the nearby houses; only a strong unity between buildings that was marked by the black color of the facades, reminiscent for me of the famous Kentucky tobacco barns.

Upon my arrival, and as I moved closer to each building, a simple and beautifully detailed façade system gave uniformity to the entire school complex. Constructed primarily from wood, vertical modules of four boards formed the entire skin of the building, while allowing windows and the integration of shading devices with occasional louvers to provide specific light for assigned rooms within the composition of the facades. At times, the modules are doubled or tripled to allow large windows and doors within the system, at other times the modules are extended to provide public entrances to the buildings (Image 3 above).

The inside of the classroom building is austere, as many contemporary school buildings are in Switzerland, but due to the expansive light sources and the shimmering surfaces of concrete walls—which are as glossy as marble—both public and classroom spaces are bathed in gentle and uniform light.

Needless to say because it is Switzerland, particular attention is given to the construction and detailing of each surface and element, noticeably of the stairwells which are treated as a sculptural element with a clever way of offering transparency from one side to the other of the stair hall (Image 4 above and 5 below).

Rediscovering

A few hours after my visit, I stumbled on a very beautiful wooden façade in the nearby medieval town of Morat. The vertical slats forming the louvers were reminiscent of what I had just experienced at the school, and suggested a direct correlation between what seemed to be an 18th century intervention in Morat and that of the school in Cugy (Image 6 and 7 below).

The interpretative aspect is subtle yet directly applicable in a contemporary manner. In this instance, accordingly to the architects, vernacular and indigenous agricultural structures were looked at, in particular tobacco barns. Not as vestiges of a farming identity, but as a building technique that I call a culture of construction; one where the use of white pine-wood (pre-grayed) “integrates itself well within the agricultural and natural landscape.” The simplicity and common sense are what I appreciated when looking at the modern school façade. Its composition is not fussy; it is rigorous yet remains playful with an ordering system that allows exceptions within the rule.

In addition, as a re-invention, the school facade partakes in a regional continuity of building over the centuries. Tradition is ever present, and when re-invented it takes on new meaning and adapts certain universal gestures within a contemporary idiom. I am not saying that the architect viewed the façade in Morat and adapted it to the contemporary design, re-invention is rarely that direct. It is the reinterpretation that takes places subconsciously because tradition is central to the experience of being Swiss and in particular in Swiss architecture. The school is a new building, yet its facade talks about the past.

Postscript

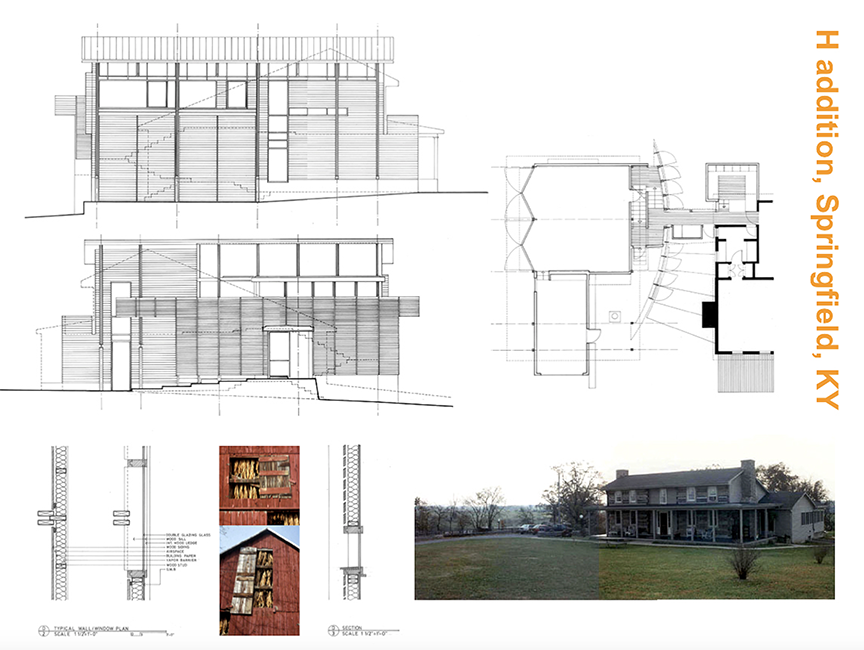

The modern school in Cugy and the 18th century façade in Morat reminded me of one of my architecture projects that ended on the drafting board. The brief called for an addition to an existing 1850s log cabin in the US and, enamored by Kentucky vernacular architecture, I opted to design a façade between the addition and the existing building as a screen made of movable louvers reminiscent of nearby Kentucky tobacco barns. Clearly my Swiss education, where I learned early on that indigenous and vernacular architecture can influence contemporary architectural production, has remained with me wherever I am in the world.