Preparing to travel with students this Fall, I could not remember how long ago it was that I took an overnight train between two major European cities. After some thought, I realized that the last time I took an international sleeper car was a decade ago, traveling from Zürich to Vienna.

All of the other times I slept on day-seat in a six-place compartment with unknown passengers. Those trips remain memorable, although not for the right reasons, especially the ones that took place when I was teaching in Venice for the College of Architecture, University of Kentucky (UK).

Architecture Competition

While there, I was invited to co-author a project with Atelier Cube (Image 1, below), an up-and-coming Lausanne firm. I was familiar with the office as I had completed a required year-long internship with them during my studies at the EPF-Lausanne. The project we were to work on now was a competition commissioned by the city of Lausanne in celebration of the seven hundredth anniversary of the foundation of the Swiss Confederacy.

There were five Swiss architecture firms invited to compete: Bernard Tschumi; Patrick Devantéry and Ines Delamunière; Max Bill (1908-1994); Luigi Snozzi (1932-2020), the latter two both mythical figures of the early and mid-century; and Atelier Cube, with whom I was working. I knew that I needed assistance in order to develop our proposal.

At that time, Andrew, a senior student, had joined the cohort of my junior students in Venice, and it seemed an opportunity for him to get some international and professional exposure prior to graduating from UK. Andrew was not only talented, dedicated, and passionate about the field of architecture, he showed promise to successfully navigate any office setting. There was no need to convince him to participate, and we both embarked as designers with Atelier Cube. We agreed that every third Friday we would take the night train to Lausanne to present progress on the project over the weekend.

Venice

Our typical train journey almost always unfolded in an adventurous manner. I will spare you the agony of purchasing train tickets in the main hallway of Venice’s Santa Lucia train station—one day you paid your ticket with a credit card, the next time they would request only cash. Lying and cheating seemed at that time for some Italian government employees a national sport. I hear that it has not changed much since then!

Aside from the ticket master’s bravado, sleeping on night trains took place in a regular six-seater compartment; often with other passengers. Trying to accommodate—modestly—a night’s sleep was a challenge, especially when passengers dismissed the natural circadian rhythm by endless conversations followed by heavy snoring. These sleepless nights were punctuated by early morning train stops, often with neon lights blaring from the platform inundating the compartment—and this, because most shades were broken or, worse, nonexistent.

Entering Switzerland, passport control was required as the Schengen Convention was not yet in place throughout Europe. National officials from both Switzerland and Italy would bang on our compartment door (of course, never in tandem) waking us up with the usual litany of yelling Passaporte/Passport. Last, and not least, while we were looking forward to the wonderful accommodations provided by Atelier Cube, when we arrived in Lausanne the city was waking up. We were tired, dirty, and smelly, but excited to show our progress after some well-deserved rest.

The luxury of traveling

With age, wisdom, and fortunately a regular salary, one can occasionally splurge on some type of luxury. This happened to me recently when traveling on a long-distance rail journey (10 hours) between Zurich, Switzerland and the Czech Republic’s capital Prague. Nowadays, night trains provide a range of accommodations and amenities that guarantee passengers a good sleep. This time, as part of a two-week travel experience with architecture students, the travel agency thoughtfully booked a single sleeper room for each faculty; what a treat!

Of course, the accommodations were incomparable to those found on the Orient Express, now called Venice Simplon-Orient-Express; an iconic train that expanded its fame through Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express. For two days between Paris and Venice (previously London and Istanbul), and vice versa, affluent passengers live on a restored 1920s moving art deco hotel (Image 2, above).

The Orient Express features only luxury cabins—some suites with separate sitting areas—three elegant dining cars, and several plush living room-bars; all beautifully decorated with marquetery, lacquer panels, and Lalique crystal. In a world where time has become of the essence, we children of the jet age take a flight half-way around the world, and complain about the journey. Fair, because that 16-hour voyage no longer represents the pleasure of travel that was exotic and sometimes romantic. Less opulent Wagons-Lits now crisscross Europe and represent the best in modern train design (Image 4, below). This is what I was on.

My Zurich-Prague night cabin

Back to reality. Upon embarking during the Fall Travel Program at Zürich’s Haupfbahnhof, we (18 students and two faculty) were greeted by the head purser. Speaking several languages fluently, he confirmed our reservations and indicated our assigned compartments. With the obvious excitement of many who had not experienced a movable home on wheels by night we retreated to our compartments and prepared for a good night’s sleep.

My room was next to the purser’s. It was modest in scale and had already been arranged for one passenger. The space was long enough to exactly fit a lower berth on one side, yet not as long as I would wish for my 6’-2” frame. Opposite the bed was a door, allowing the cabin to extend into the next coupe, thus allowing groups or a family to share the same space. This was the case for several students who kept the door open between cabins, which made discussions livelier, until my colleague texted them to be more discreet as the entire wagon-lits that night was not exclusively ours (Image 4, above).

Opposite the entrance to my coupe, was a large square window with a view on the landscape, at least a view which I would wake up with in the morning, hours before arriving in Prague (video, below). Above it was a transom, which I suspect carried the ventilation ducts for each cabin. Below, and to its left, was a built-in corner cabinet that provided a sink, mirror, and amenity package with immaculate white slippers, and a towel. In front of the connecting door was a ladder, giving access to the second and third berths if the cabin had other passengers.

Additional berths

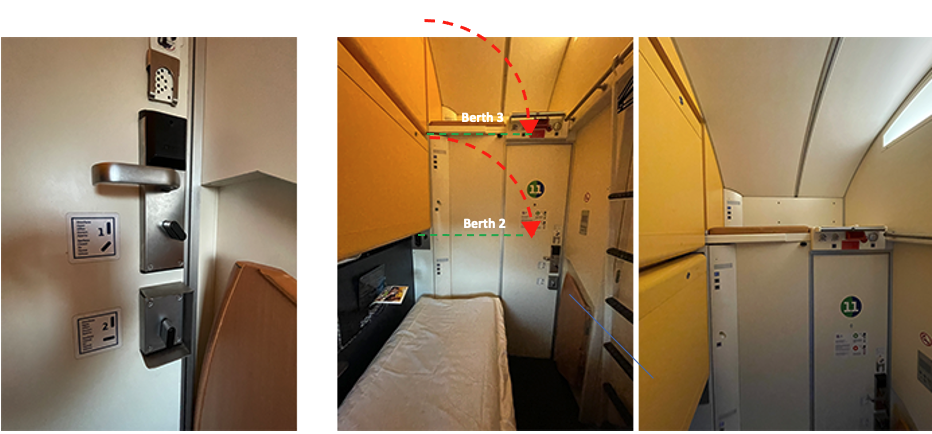

Looking back towards the entry, was the door with two locks (the lower one for the purser in case of emergency), a place to set the entry key card, and to its left, numerous square buttons controlling the cabin’s lights, heat, A/C, and loudspeaker. Above the door, and over the carriage’s corridor, was what I initially thought to be ample space to set luggage without encumbering the narrow space in front of the bed (Image 4, above right).

However, at closer look, I noticed the small knobs on the large horizontal yellow panels situated over my bed. I realized that they were the two additional berths that could be pulled down, thus creating a cabin that accommodates three passengers. What I initially thought of as space for luggage clearly was part of the top berth as similar light switches were provided there. Most importantly, the third pull-down panel was shorter as its full length was reduced because of the window transom (Image 4, left above). What an ingenious way of working so many spatial components within such a tight space.

Finally, the view looking up from the bed was of the curved ceiling, which mimicked the train’s exterior rounded roof. It was formally complex with all the handles, harnesses, coat hangers, and A/C outlets, yet reminded me (sadly) of the minimum existential space I was going to travel in over the next hours.

Middle of the night

When nature called, I proceeded to look for the restroom typically found at one of the two ends of a sleeping carriage. The corridor was eerily deserted at this early morning hour and gave me an understanding of how each cabin was defined from the corridor’s side. For the cubicles that could be joined internally, their entrance doors were adjacent, but divided by an elegant vertical light illuminating the doors from the handle upwards.

The remaining section of wall was slightly curved, providing visual movement between doors, and a modulated scale for the entire corridor. For the other cabins—one that did not connect internally—another rhythm was established between the doors, all the while maintaining the feature of a slightly curved wall, punctuated by the entrance lights (Image 6 above).

Public bathroom

Arriving at the restroom, lo and behold, I realized that not only was there a commode but also a shower as indicated by the symbols affixed on the outside door. While it took some time to open the door with my key card—I guess I was clumsy at this time of the morning—the space was a marvel of interior design. Triangular in shape, all amenities were positioned in an extremely efficient manner.

To the left of the entrance was the commode, a mirror, and a sink cabinet similar to the one in my compartment, although this one did not open and close. To its right was a shower stall of rather generous dimension. What was exceptional, was how the designer was able to package everything in such a tiny space. I marveled at the ingenuity of the bathroom’s functional layout and its immaculate cleanliness. All of the above, almost made me forget the real purpose of my visit (Image 7 above and 8 below).

Morning

Luckily, for our circadian rhythm there was no border control, and upon awakening we were well into the Czech Republic. A generous breakfast had been brought to my room a little earlier, as the purser informed us, much to my disappointment, that due to construction on the train line, we would disembark before the city and arrive in Prague by bus. Before leaving, we checked on the students and reminded them not to forget any personal belongings (a successful reminder this time, but not on a later journey). The purser, in a last gesture of professional curtesy, helped us with our luggage; luggage that expanded and became heavier as our journey unfolded across Europe.

Conclusion

Taking a night train is memorable in many ways and for me it was a reminder that a well designed space can be achieved even in the smallest quarters, such as a train compartment, an airplane, or a boat. I’ll continue to remind my students of this, as they tend to expand space to accommodate their every whim, rather than focus on the essential.

How many spaces of meditation, or views toward the living room have I heard discussed during desk crits, when really it is left over space that does not belong to the program brief. I’m not saying that additions are forbidden. For example, a library and a staircase could be combined in an innovative space, rather than creating a library without character. This is what I love about architecture, the quest for a thoughtful economy of means, that uses functions in a poetic way.