The need for disciplinary integration: Part 1. I have always considered teaching architecture, and perhaps more importantly the practice of architecture, an all-encompassing endeavor. And this, despite observing year after year, endless jargon among my colleagues promoting the discipline of architecture as autonomous and self-referential.

Some even endorse the term non-referential to legitimize an architecture theory, that, I believe, is a disguise for a new formalism; a clever makeover to reconnect modernism’s dogmatic and idealized approach with today’s elitist architectural production. However, regardless of these positions, I have always preferred the idea that design is a holistic endeavor toward an everyday or silent architecture (yes, with a lowercase a), rather than the celebration of an architect’s genius.

To my dismay, some of my colleagues do not promote one of architecture’s important charges: namely, to balance creativity with the nature of solving problems. In academia, the push to define architecture as autonomous remains among some the source of a certain arrogance, and, sadly, has predisposed some students to think that they can stand out by being exclusive in their intellectual position. This self-confidence is the result of many influences, but, to me, most important is that historically in Western society, Architecture (yes, with a capital A) has for over the past two millennia “…laid claim to being the ‘mother of the arts,’” thus an architecture based on grammar, syntax, and vocabulary.

While I regard and encourage scholarly research to anchor students with an appreciation of architecture’s lineage, at an undergraduate level students have primarily entrusted us to deliver an intellectual edification that will give them the confidence to receive “the education of an architect,” while also leading to the practice of their discipline within a professional context, namely building and not simply theorizing (the latter belonging to the world of critics, historians, and social commentators). This balance between theory and practice is in fact the richness of my own education, which is polytechnic in its nature and part of the identity of the school where I currently teach.

It is customary that a few students will choose a career in teaching, getting a master’s degree and possibly pursuing a PhD, thus, it is critical that they acquire a strong historical and theoretical foundation to allow them to pursue their dreams. Whether continuing in practice or academia, my argument remains that there should be no disconnect between the practice of architecture and the study of architecture theory and history. This is particularly true within the design studio; a belief which is in direct opposition to the minimum required content defined by the accreditation body (NAAB).

Vernacular architecture

Thinking of my art form as an inclusive undertaking, I understand that this conviction stems from my polytechnic education at the EPF-Lausanne, and a subsequent teaching position at the ETH-Zurich. As early as in my freshman year, faculty introduced us to architecture (with a lowercase a) through the appreciation of vernacular architecture; a way of building that is “characterized by its reliance on needs, construction materials and traditions specific to its particular locality.” Professors Frederic Aubry and Mario Bevilacqua, along with Aubry’s First Assistant Plemenka Soupitch, created Lausanne’s first-year identity and were instrumental for a generation of students.

The locus of our learning was to understand how culturally indigenous traditions formed an immense and varied repertoire of architecture; an attitude that is perhaps an important part of the humble richness of Swiss architecture. Later, at Cooper Union in New York City, I rediscovered the meaning of vernacular through the teaching of Raimund Abraham and the work of his friend Walter Pichler. The great lesson for me was to design space that relied on creating a physical reality. This was imparted as an integrative process involving multiple stakeholders.

Indigenous builders relied on inherited gestures respecting site, climate, structure, and material constraints. These non-architects grounded their objects within norms and attitudes defined in material culture and social patterns of behavior. When I came to teach at the University of Kentucky, I was made aware of Shaker architecture; this reconfirmed my past experiences. The unpretentious complexity of their architecture and vision of life, added to my belief that space was not seen as solely a formal endeavor, but a cultural act that responds to constraints that often are expressions leading to tangible problem solving.

Over the years, I embraced in both my practice and teaching the need for other disciplines to contribute and play a key role in the creation of places. Architecture, as I often mention to my students, does not have to resolve all spatial problems that one encounters when designing. This is at the heart of my continued interest in having students learn early on that the discipline of architecture is a collaborative act of creation between multiple disciplines.

This is perhaps the reason I have always sought college settings—mostly Land-Grant universities in the US—that housed multiples disciplines, including architectural engineering, construction management, historic preservation, interior design, industrial design, and landscape architecture, in addition to architecture. Of course, each of the colleges I have associated with had created their own portfolio of programs. For example, the institution in which I currently teach offers interior design, industrial design, landscape architecture, and architecture, but to my regret, is soon to retreat to being a school of architecture without its previous connectivity between disciplines.

In my case, and this since my early days at the University of Kentucky, I have as a faculty—and later as an academic leader—encouraged students and colleagues to undertake collaborative endeavors between disciplines. Yet, while many disciplines are housed under visionary college names established in the early 1960s (e.g., College of Architecture and Environmental Design at Cal Poly), the on-ground reality remains that it is more challenging to enact collaborative efforts than to foster an identity that is silo-centric.

Conclusion

The reasons are multiple, and most often faculty claim that there is little time to explore more formalized, integrative, and collaborative endeavors. Certainly, grassroots undertakings by a number of faculty continue to promote punctual collaborative design thinking. But since my time at Cal Poly, I have not seen a formalized approach to integrate students from various disciplines within one design studio (i.e., such as construction management, architectural engineering, and architecture). The richness of that program meant that students were fully integrated in a design studio where they worked issues out, rather than retreating after lectures to their disciplinary units, thus preventing the idea of true inter-disciplinary complicity.

I hope that as education adapts to the 21st century, students are allowed to experience a more integrative approach to architecture.

Related blogs

The need for disciplinary integration. Part 2

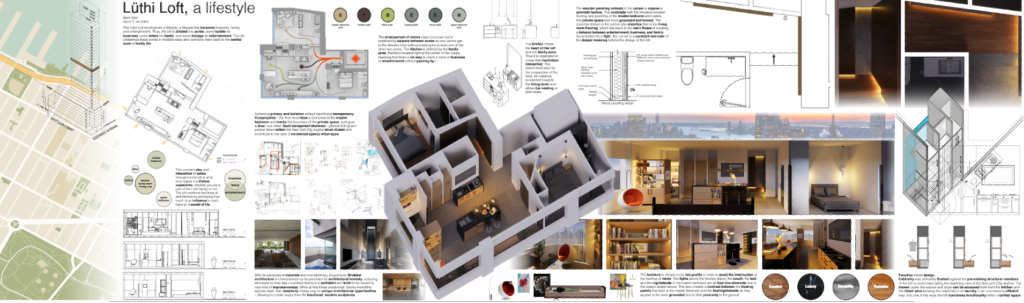

Final architecture presentation drawings

What a wonderful treatise— What a great source for a jumping off conversation with colleagues. Thank you so much

Yes, perhaps one day when transparency and trust in creating an enriched educational model is again timely.

Thanks