Tita Carloni Church facade in Ticino. Since the founding of the Federal Charter of 1291, Switzerland has remained an open-minded country that has sought to balance tradition with innovation. This is true in many aspects of Swiss life, and is particularly visible in matters related to art, religion, education, and perhaps most importantly, Switzerland’s principle of federalism.

Key to this healthy mindset is a belief in the ideals of democracy and the ensuing responsibilities that come with it.

As an architect and holder of a Swiss passport, I admire another important Swiss identity; one that embraces and encourages the safeguard of local patrimony. Assisted by federal and state development policies, citizens are committed to the enhancement of their environment; especially when dealing with vernacular or indigenous buildings located within their respective communities.

The 2018 Davos Declaration

In 2018, this Swiss commitment to existing heritage, was furthered at the level of the European Community through the 2018 Davos Declaration. While the entirety of this important document is close to my heart, two components are foremost in my mind. First, to confront urban sprawl, the notion of culture and the need for design values is critical in maintaining regional traditions and identities. Second, and as an offspring of this statement, is that “…the crucial contribution that a high-quality built environment makes to achieving a sustainable society, is characterized by a high quality of life, cultural diversity, individual and collective well-being, social justice and cohesion, and economic efficiency.” A great vision for the Old Continent.

Ticino

While traveling in rural Ticino, the Italian speaking region of Southern Switzerland, I rediscovered charming historical villages perched high up on the mountains. Their spatial configuration was the result of careful planning of tightly knit urban clusters defined by domestic, public and agricultural buildings. Outside these village centers are idyllic farmsteads with steep farm lands punctuated by the gentle sound of cow bells. As a sustainable entity, the overall organization of these settlements never fails to include commercial, governmental and religious institutions with their respective public plazas; modest in scale, yet majestic in their sense of monumentality.

Typically, one finds that the church and adjacent cemetery take prominence within the historic town center, and regardless of their religious denomination, churches are typically expressed through a bell tower and imposing entrance façade. One may not think of a rebuilding or recladding of a historic church façade as a design project, but this is what famed Swiss architects, Tita Carloni (1931-2012) and Mario Botta (1943-) undertook in two separate instances, with great creativity and personal sensitivity.

Tita Carloni

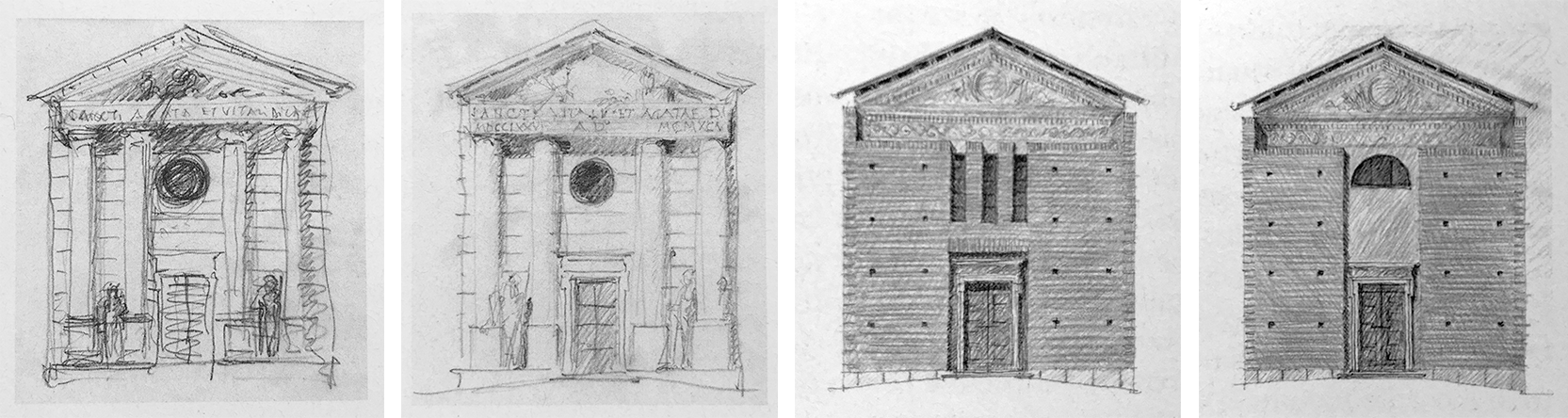

Designed by Tita Carloni (above and below images) this project dates back to 1996. The church of the Chiesa dei Santi Vitale ed Agata, is located in the village of Rovio overlooking the southern part of Lake Lugano. The church’s construction may be traced back to the Romanesque period, with a first modification of its façade and interior to a neoclassical style at the end of the 18th century. Due to the poor state of preservation, it was again modified in 1996, but this time with a striking proposal that attracted my attention upon entering the village. The façade immediately stands out in both its formality and abstract monumentality.

Borrowing from a classical vocabulary, Carloni uses the tripartite division of a temple frontage to quote historical periods through recognizable forms, decorative elements, and a tongue-and-cheek strategy of imitation – often called pastiche. This mindset reflects the period in which the architect was working, and his interest in using a postmodern language to modify the existing façade, lends it both a sense a familiarity with the previous 18th century facade, while giving the building entrance a new personality.

Several moves give this project a contemporary look: abstracted capitals; use of regional and Roman materials such as terracotta and Saltrio white stone; the lack of traditional ornament that historically gave church facades their depth; and the superimposition of new and old (the door entrance is original and dates back to the late 17th century).

Evolution of the facade

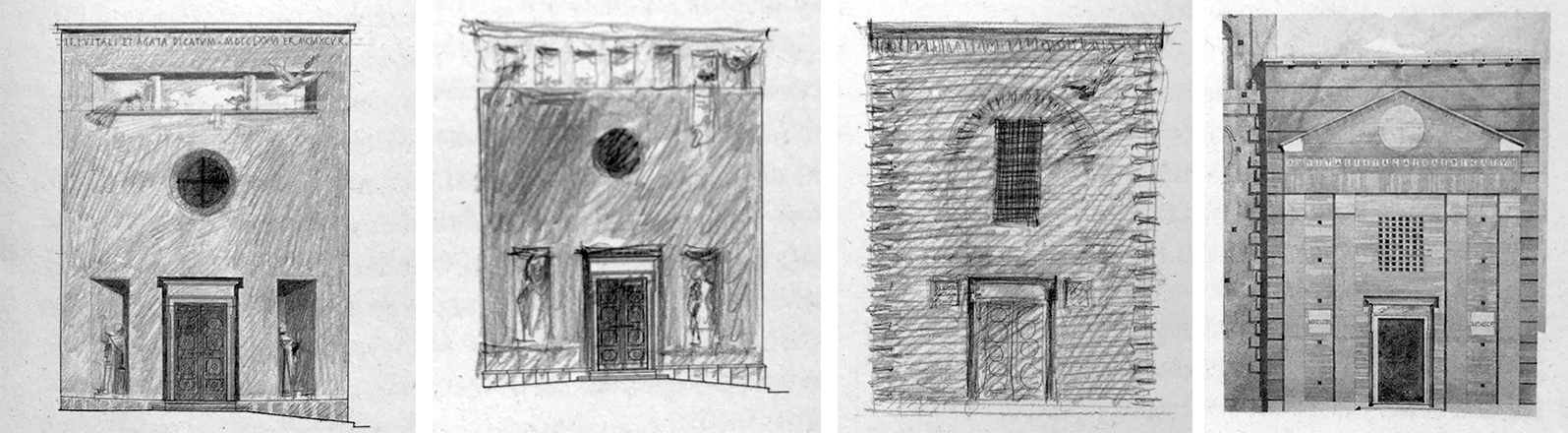

While some claim that the project does not fit into the context of the existing church, several subtle moves let us know of the architect’s intention to seek continuity between the past and the new. For example (left hand color image above), the structural corner stones of the base of the bell tower are represented on both sides of new façade. Through a change of color at every twelfth brick course, stability of the edifice is symbolically represented without resorting to mimicking old building techniques.

Final project

What is perhaps most remarkable in this project is the rectangular background that supports the expression of the temple form. Like a theatrical stage set, it acts as both a framework for the emblematic idea of an entrance, and allows it to be seen as a flat surface (like a mask celebrating at the scale of the town) the ceremonial role of the church within the community. Such simplicity and power of suggestion is achieved through a set of iterations; a process shown above through a set of eight pencil drawings where the architect explores the 18th century church façade by abstracting its original composition, before returning to his first intuition, now rendered in a new way.

Church facade in Ticino, Switzerland: Part 2

The Igualada Cemetery