Hubert Robert: Painting as a source of knowledge. I will admit that my passion for painting is equal to my passion for architecture, although I have practiced and taught architecture for many years and, for fear of embarrassment, never taken my personal attempts in the art of painting seriously. During my own architectural studies, a faculty member who was also a graphic artist, introduced me to the foundation of the science of color. She enticed me to learn how the subjectivity of color could trigger sensations; this would become the source of a lifelong astonishment and appreciation of color and painting.

Paralleling this rigorous study of color, my first formal introduction to painting was conditioned by the architectural faculty at the Ecole Polytechnique Féderale de Lausanne (EPFL) who were extremely knowledgeable, but overtly influenced by early 20th century revolutionary artists. It would only be fair to acknowledge that many of these professors were directly influenced as students by the first generation of early modern architects and artists who were still living when they were beginning their careers. In the early 20th century, there was a strong complicity and influence between art movements and, in particular, from painting to architecture. Thus, it was legitimate that the faculty at my school reflected their strong adherence to the ideological tenants of those masters.

Cubism

This all led to my true revelation about architecture through the teaching of Robert Slutzky (1929-2005), a painter trained at Yale under exiled Bauhaus professor Johannes Itten (1888-1967), and co-author with architect and scholar Colin Rowe (1920-1999) of the seminal essay Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal (1963). In hindsight, it is ironic that Bob became a key mentor in my architectural training and teaching, since he was first and foremost a painter and professor of art. Doubly ironic, as it reminds me how the departmental leadership at my alma mater in Lausanne were visionary and courageous in promoting a holistic approach to the education of an architect, one that was timely, visionary, and truly interdisciplinary.

Through these three experiences, all under the auspices of painting, I became particularly enamored with cubist and purist artists represented by George Braque, Juan Gris, Pablo Picasso as well as the paintings of architect Le Corbusier (Image 1 above, left to right). Eventually, many others art movements, with their respective artists—de Chirico, El Lissitzky, Itten, Malevich, Mondrian, Sant-Elia, Schwitters, and van Doesburg to name a few, circled around my key original protagonists. All of them were sources of inspiration to me, but remained at that time, somehow sadly, only foundational material to the learning of architecture, and in no way the pretext for trying my hand at painting.

However, I have always loved to draw and feel at ease in this endeavor. Beyond a daily obsession with sketching for myself and with my students, I am fond of drawing dogs with a particular delight in getting their eyes right. Right, not in terms of precision (although I am Swiss) or being perfectly faithful in depicting reality, but more in suggesting their inner soul; I believe their eyes give us a profound understanding of their emotions and of who they are (Image 2 above drawn by author).

Pictorial interests

Within this autobiographical history between color, painting, sketching, and architecture, and an education which was solidly grounded in modern art, I was drawn more to a painting’s subject matter; a narrative message conveyed through the artist’s genius between realism and abstraction. This awareness expanded my repertoire of artists to the 15th century International Gothic period which included Pisanello, Simone Martini, and Lorenzetti, and mid 20th century artists such as Bacon, Diebenkorn, Hockney, Morandi, Hopper, Rivera and Thiebaud.

Le Louvre, Paris

Image 6: Le Louvre -Project to illuminate the Gallery of the Museum by the vault, and to divide it without removing the view of the extension of the room, also known as Project for the Transformation of the Great Gallery. Hubert Robert (1796)

Image 6: Le Louvre -Project to illuminate the Gallery of the Museum by the vault, and to divide it without removing the view of the extension of the room, also known as Project for the Transformation of the Great Gallery. Hubert Robert (1796)

Image 7: Le Louvre -Development project of the Grande Galerie du Louvre. Hubert Robert (1798)

Image 7: Le Louvre -Development project of the Grande Galerie du Louvre. Hubert Robert (1798)

During a trip to Paris, where I had the luxury of spending several days at the Louvre, I enjoyed focusing on paintings, and systematically moving from gallery to gallery, from British to Italian, from Dutch to Spanish and French painters, from art movement to art movement, all with no pressure or preconception.

The experience was delightful, refreshing, and, above all, educational. In this process, I rediscovered one of the world’s greatest museums and renewed my affection toward French painter Hubert Robert (1733-1808). Beyond his famous paintings of the imaginary, and his project for the Grande Gallerie at the Louvre, I was familiar with many of his vedute (view paintings) and capricci (imaginary view paintings) of urban landscapes, which depict the artist’s predilection for monuments and antique ruins of bygone empires (Image 5 above).

Image 8: Le Louvre- Hubert Robert by Vigée-Le Brun (1788)

Image 8: Le Louvre- Hubert Robert by Vigée-Le Brun (1788)

Hubert Robert

Hubert Robert is not singular in his interest in those genres of paintings, and the city of lights was no rival to Panini’s paintings or the etchings of Piranesi’s of Rome, Canaletto’s of Venice or Bellotto’s of Dresden and Warsaw—often created as souvenir paintings for young British aristocrats returning from the Grand Tour.

Yet, in one of those majestic exhibition rooms of the Louvre, I discovered a 1786 painting by Hubert Robert titled Demolitions des maisons du pont de Notre Dame in 1786 [Demolition of the houses of the Notre Dame bridge in 1786], one of three versions (Image 9 below) depicting the same subject matter, but with slight variations. All three versions of this painting are featured at the end of the blog.

Image 9: Hubert Robert, Démolition des maisons du pont Notre-Dame, 1786. Oil on canvas, 73 x 140 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Image source: Henri T. de Hahn

Image 9: Hubert Robert, Démolition des maisons du pont Notre-Dame, 1786. Oil on canvas, 73 x 140 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Image source: Henri T. de Hahn

The scene of the bridge is distinctive within Robert’s oeuvre, as it chronicles a unique moment in the transformation of the cityscape of Paris. Progress unfolds while expressing the physical scars due to the ongoing destruction. In this painting, the subject matter is no longer simply evocative and Romantic, but the reality has become spatial and synonymous with a sensory landscape—one can hear, smell, and feel the labor of the demolition of houses.

The stone bridge, the Pont de Notre Dame, is said to be the oldest crossing place in Paris and its importance is due to its location on the former Roman Cardo, a major street from north to south: an important traffic axis found in any Roman settlement. The history of the Pont de Notre Dame dates back to Roman times (1705 maps of Nicolas de Fer), and reflects constant destruction and rebuilding in the same location due to a variety of reasons, including flooding of the River Seine, collapse of the bridge, the 1786 removal of houses for sanitary reasons, preservation of the structural stability of the bridge, and, finally, its current version built during Haussmann’s transformation of Paris in 1853. Fascinated by the almost mundane subject matter of the painting, my mind wandered while I stood in front of it, and, like a Frenchman, I started to classify, systematize, and order topics that the painting brought to my mind.

Architecture

Architecturally, the typology of the houses suggests their design is from the Renaissance period where the first urban ordinances in Paris legislated a strong and uniform street front (further research at home revealed that the houses on that bridge were the first in Paris to have house numbers). The row houses, three-stories tall, were narrow, with an attic and steep gabled roof. They were located on both sides of the bridge defining a new streetscape where light and air provided a place of economic activity, the latter suggested by the large wide arches at ground level. The scale of the houses was in direct contrast to those on the Pont au Change, a bridge located upstream on the Seine and seen through the arch in Hubert Robert’s painting.

While studying the painting, I remembered the famous plan of Turgot where the bridges—both the Pont de Notre Dame and the Pont au Change (next bridge downstream)—featured houses of a more monumental scale, thus the suggestion that in Hubert Robert’s painting, he took artistic liberty in the depiction of the scale of the houses being demolished (Image 10 above engravings from left to right with indication of the Pont de Notre Dame: Plan de Truschet and Hoyau 1552, Matthaus and Caspar Merian 1655; and Plan Turgot 1734–1736).

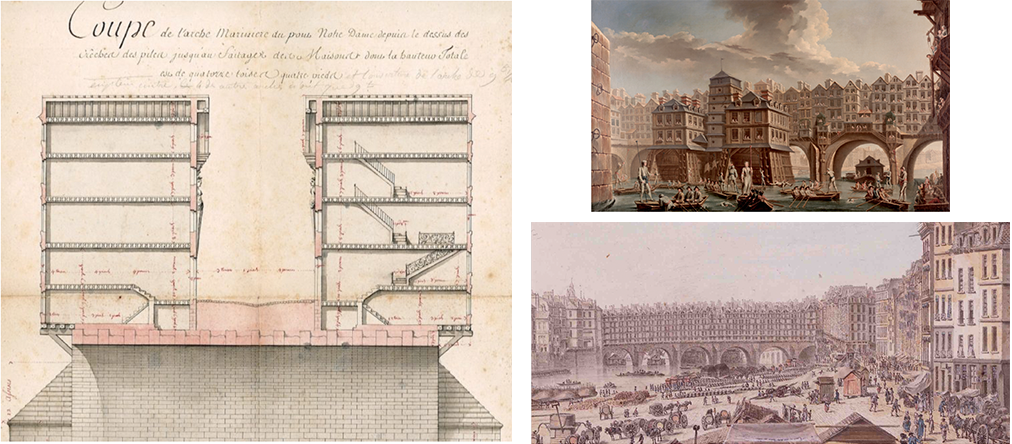

However, further research refuted my initial conclusion about Hubert Robert’s artistic liberty. The discovery by M. Decossan of a cross section through the Pont de Notre Dame, in addition to two paintings of the same subject matter by Nicolas Raguenet and Louis-Nicolas de Lespinasse (Image 9 above from left to right), indicate that Hubert Robert’s painting recorded the interior facades (four stories from the street) rather than those facing the Seine (five stories). While remaining interpretative, the painter depicted with some accuracy and rigor the remaining houses on the bridge.

Urban

At the urban scale, the painting suggests that Paris is undergoing tremendous change and holds the promise of transforming from a medieval city into a mature metropolis. Already the Pont Neuf (“New Bridge” completed in 1607), which is depicted as the third and last bridge seen through the large arch past the Pont au Change, no longer has houses. All houses on bridges across the Seine were to be removed. This was to promote new sanitary regulations throughout the city, and was part of an interest in providing views of the Seine for the new urban aesthetic.

These changes were also a direct consequence of a new geopolitical stability for Paris and France. The existing defensive wall systems built under Louis XIII had slowly been removed to the north of Paris, and with the successful territorial conquests of Louis XIV, Paris was now an open city. However, a robust program of fortifications was built at the metropolitan scale, for both taxation on incoming goods and as a defense system due to two centuries of continued wars in Europe. Of interest, there are only two bridges in the world which today continue the tradition of buildings occupying the edge of the crossing. They are the Rialto in Venice, and the Ponte Vecchio in Florence, both thriving as centers of commerce (Image 12 below).

Engineering

Through the lens of an engineer, the bridge’s six arched barrel vaults (Hubert Robert’s painting only depicts five) express the static limitations of stone to span the entire river (the 1853 metal version easily spans 180 feet). Each shallow arch (not a perfect half circle as it would have made the bridge too high to meet existing street levels on either side of the river bank) complements the other by transferring the resulting diagonal forces from each arch to a single vertical force brought down to the foundation. The expression of robust buttressing indicates both the need to protect the piers from erosion due to forces of water in the Seine, and to avoid the possible devasting consequences of impact from large debris or vessels that would have torn away critical foundational elements.

While a study of the painting brought many other topics to mind (i.e., composition with the subtle vignettes that anchor the painting within important monuments of Paris; accentuation of several horizontal lines; and, the definition of pictorial planes recessing and defining the urban space), I was intrigued by the visual reference that Hubert Robert set in place with the focused attention on the arch that reveals the bridges beyond.

The intention not only emphasized a moment of spatial depth showing the history of the other two bridges, but, knowing that Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1788) was a contemporary of Hubert Robert’s, it seems evident that there was a subtle reference to the visual and illusionary complexity offered in Piranesi’s Prison series in the complex treatment of the arches painted by Hubert Robert (Image 13 below).

Upon moving to another painting, or if I remember correctly, going to enjoy a French croque monsieur at the museum’s Café Marly, I pondered how what I saw in Hubert Robert’s paintings carried powers of suggestion from within its subject matter and, above all, how painting has the ability to engage viewers to lend their own autobiography to bear on the meaning of the painting’s narrative.

Postscript: Three iterations on the same theme

Paintings, such as those by Hubert Robert, are iconographical documents that extend the visual delight to serve as cultural and societal testimonies for the posterity of urban historians, and all those who visit these great museums.

Other blogs of interest on painting

Architectural Education: valuing your mentors -Robert Slutzky. Part 2

Still lives by Ben Nicholson

Simone Martini: three principles of settlement

Le Baron Tavernier: a cafe terrace in the middle of the Lavaux vineyards, Switzerland

Edward Hopper