Question of Pedagogy, Part 1. As a student, I remember fondly our first studio day of the semester. It was always magic and full of promise. The faculty member would introduce her or himself, describe the expected requirements for a healthy studio culture, and proceed to share thoughts on the pedagogical intentions offered by the program’s brief.

Question of Pedagogy, Part 1. As a student, I remember fondly our first studio day of the semester. It was always magic and full of promise. The faculty member would introduce her or himself, describe the expected requirements for a healthy studio culture, and proceed to share thoughts on the pedagogical intentions offered by the program’s brief.

As students, we came to like the pedagogical introduction, as it was almost a tacit contract between us and the faculty and we did not have to second guess the overarching intentions of the studio context; i.e., what were we expected to learn during the semester. In other words, the faculty let us know that the learning outcomes of each project were beyond the magic one-liner that I also quickly came to include in my syllabi when I became an instructor.

This straight forward approach by our studio professor never implied that students lacked the freedom to investigate their design as they saw fit. Despite a traditional European master to student hierarchy, there was never a single project that mimicked the faculty’s professional output, and all of my faculty professors were principles of their own architecture firms.

Paralleling this style of teaching, we had theory courses that emphasized two important aspects of learning. One was dedicated to theory of the project and the other to theory of the act of designing [projecting].

- Theory of the project emphasized theoretical concerns that would legitimize the project within the discipline of architecture. For example, we learned in the seminars—that were always integral to the design studio—about the Five Points of Le Corbusier; the epistemology between walls, columns and mixed systems; and the important contributions of modern plans such as the Prairie and Usonian plans of Frank Lloyd Wright, the Bauhaus plan of Walter Gropius, the de Stijl plan of Gerrit Rietveld, the Raumplan of Adolf Loos and of course notions of “spaces serving” and “spaces served” as defined by Louis I. Kahn.

- Theory of the act of designing was to assist students in understanding their project; building up general skills and trust in how to develop an architectural process, one that aimed for the completion of a successful design. We learned how to diagram conceptually in drawing and in model, how to develop a partie, the meaning of sequencing rooms and spaces and other topics that would often corelate with those developed in the theory of the project

These seminars were also an important moment where we were taught to think in an integrative manner. We learned a respect for INTEGRATION, as compared to design studio projects that emphasize the primacy of design followed by the imposition of a site strategy, and a structural system sprinkled with a semblance of construction to fit the parti. Often in these situations students never think of detailing beyond simply learning the obvious principles to pass their registration exams. My own studies explored the true value of a polytechnic education, one that sees ideas articulated conceptually and professionally, with equal respect and commitment. Perhaps this was because of the nature of the curriculum leading to registration upon graduation.

In addition, during my studies, the preoccupation of an already holistic notion of a culture of construction was reinforced by the 1978 death of Italian architect Carlo Scarpa, a time I remember forever as it corresponded shortly before the beginning of my architecture education. His death sparked widespread international recognition and gave renewed meaning to Scarpa’s oeuvre. This moment reinforced that the thesis of architecture is about space and how to conceive and construct it.

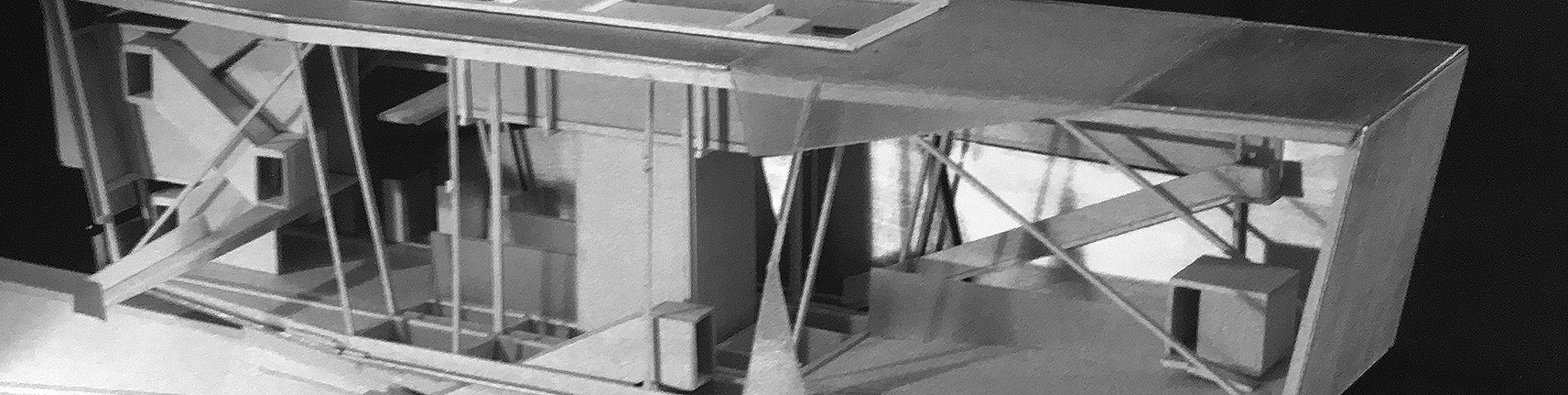

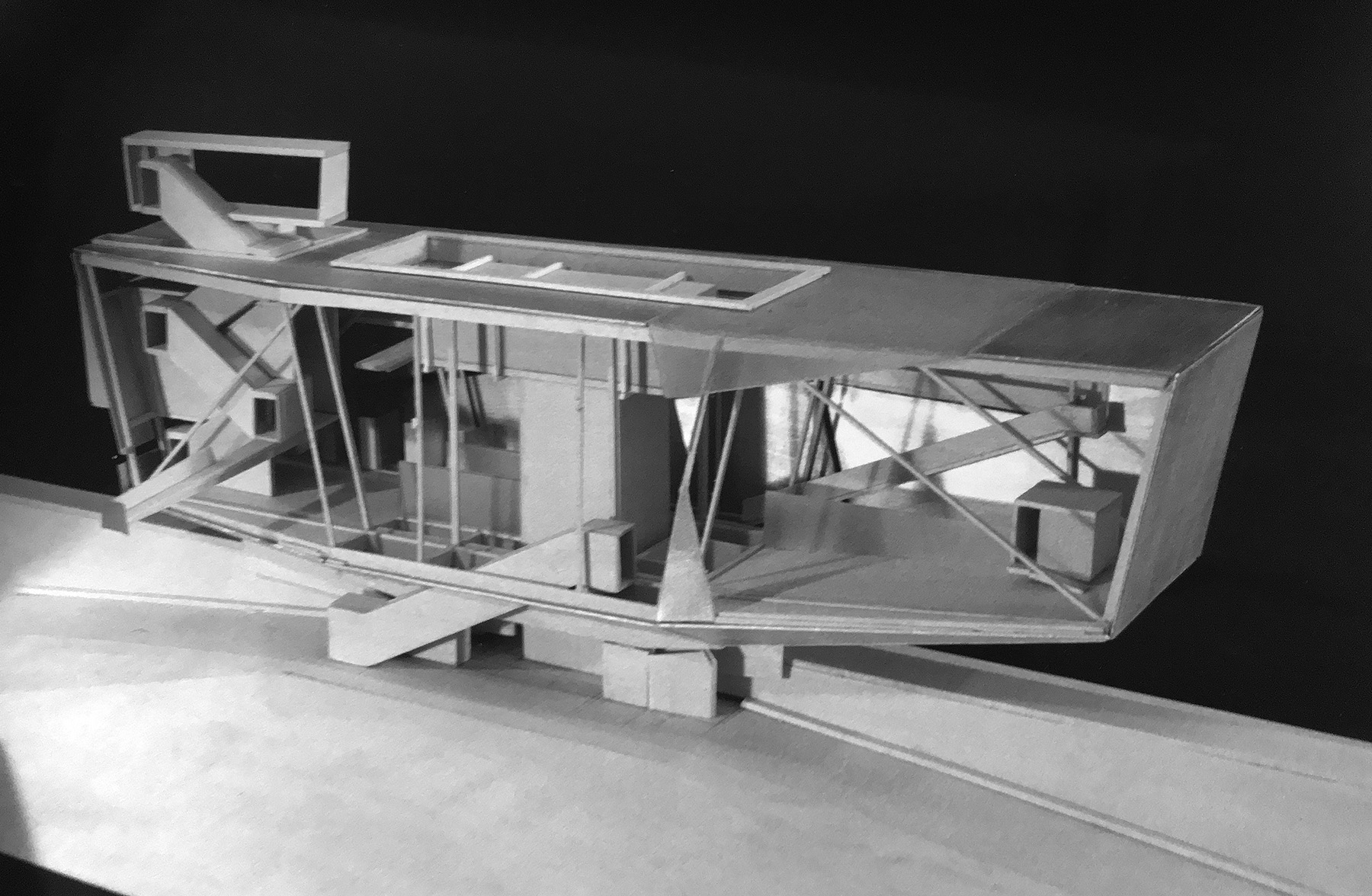

Student project: model of drive-through bank

Student project: model of drive-through bank

Later in life, teaching a third-year design studio seemed a welcome opportunity to elaborate a new brief that emphasized not the project per se, but the notion of process. Having taught second-year design studios for years, I wondered with this more advanced group if the traditional ‘beginnings’ of a design project could be circumvented by avoiding weeks of personal research—often resulting in an endless intellectual procrastination with few tangible deliverables. I decided to experiment by condensing the initial “conceptual thinking” to a thirty-minute charette followed by a three-week intense refinement and final presentation of the project.

Student project: model of drive-through bank

Student project: model of drive-through bank

The premise was simple: when it was their turn to “present” on the first day, each third-year student chose a sealed envelope containing a specific program. I remember picking topics ranging from a funeral parlor to a laundromat-bar, a drive-through bank, racket ball, cinema, toll both, post office, drive-through medical center (easily imagined today as a Covid-19 testing center), gas station, and a small bowling alley.

As a side note, today I would not repeat the program of a funeral parlor! Too complex emotionally for students in third year. However, in subsequent years, I found that a cemetery as a studio project was a topic of great interest for students, especially given that many majestic cemeteries were designed by architects.

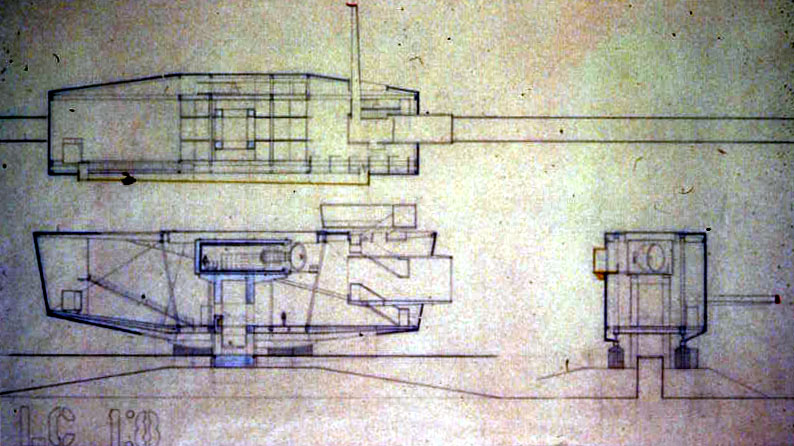

Student project: plans, sections and elevations of drive-through bank

Student project: plans, sections and elevations of drive-through bank

Each student opened their program envelope as their time in front of the class began. After a moment of surprise, hesitation, and often bafflement, and the participation of the audience in the surprise, the student then had thirty minutes to develop their concept in concert with the dialogue between peers and faculty where questions were continually raised to provoke the student to express their convictions and doubts, argue their position, and refine the basis of their intuition and rationale vis a vis their concept. This was done in the most public manner—with diplomacy and equal fervor—through sketching and diagraming and ended with “the concept”.

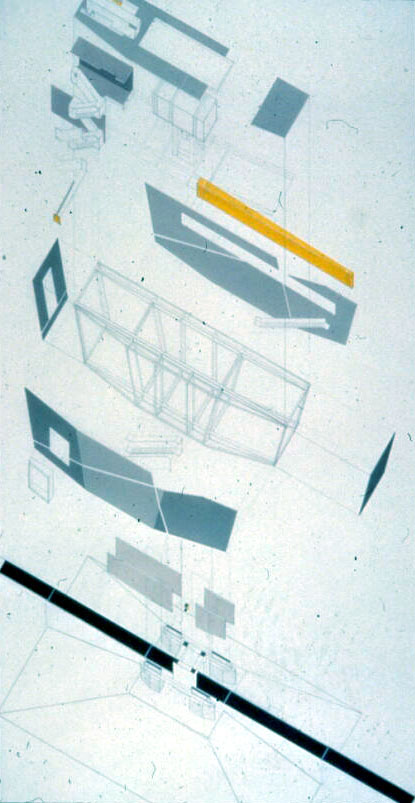

Student project: axonometric of drive-through bank

Student project: axonometric of drive-through bank

I remember the intensity of those discussions as the ideas that were tossed about never failed to inspire both student and audience. Yet, while there was great freedom to develop any mundane or wild idea, the difficulty always remained for the students to be able to hold the concept so that the second phase of the charette would be dedicated to implementing and presenting their idea first and foremost as an architectural thesis with the typical systems of notations such as plans, sections, elevations, axonometric and an accompanying model (see above image). To not burden the students with more complexity in a tight timeline, each program had as its site a simple flat plane defining a horizon that could be manipulated in accordance to their overall concept.

After the completion of the initial public stage (establishment of “the concept”), each student had three weeks to develop their scheme. We would return to desk crits and weekly studio reviews, with the caveat that the parti (a Beaux Arts idea defining a spatial organization of the building based on functional requirements) could not be changed; simply refined to exhibit the initial premises developed during the first charette.

The end result was mixed, as it is in every studio, as the pressure of time was handled differently by each student. And yet, all students’ initial ideas were strong and visionary as architecture should legitimately be, and this despite the modesty of each of the assigned programs and the initial public charette to produce their concept. The important lesson is that the notion of having all the time in the world may not be essential to producing great work, as self-imposed pressure, commitment and strategic thinking are important vehicles in the articulation of strong ideas.

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy. Part 2

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy. Part 3

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy. Part 4

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy. Part 5

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy. Part 6

Architectural Education: The nature of IDEAS