The nature of being: Shaker architecture. Shaker Village at Pleasant Hill is located near Harrodsburg, Kentucky, and remains on a list of my fondest places in America. Prior to moving from New York City to Kentucky, I remember a phone interview with the architecture dean at that time.

Upon concluding our hour-long conversation, he asked if I had any questions. Not realizing that he intended this as a near job offer I responded naively, asking, Where is Kentucky? Lo and behold, my genuine inquiry secured me an on-site interview, launching a tenure of 19 years at the University of Kentucky, and most importantly, the beginning of indelible and cherished friendships accompanied by the mentorship of inspiring, genuine, and extremely talented students.

Lexington, Kentucky

Being a city boy, my years in Kentucky were my chance to discover the essence—or the meaning—of one of the most beautiful rural landscapes. The Bluegrass region. Rolling hills punctuated by vernacular and indigenous structures, tobacco barns painted deep black contrasting with the white winter snow, distinguished 19th century antebellum homes, and historic turnpikes radiating from the city of Lexington.

These toll roads, as they were also called, were lined by world-famous horse farms surrounded by pristine paddocks, lush grazing fields, memorable white fences, and legendary limestone rock walls—the latter built by Irish immigrant stonemasons who “passed their craft on to black slaves that became masters of the craft of building rock walls.” I had come to appreciate my newly acquired relationship to nature, “…the forest and field, sun and wind and sky, earth and water, all speak the same silence language…” and learned how to listen and unravel the vocation of a site, rather than imposing my limitations and young preconceptions on a place that I did not fully understand.

Image 1: Google images of the Bluegrass landscape outside of Lexington

Prior to my move “down South,” or more appropriately to the Commonwealth of Kentucky, which was a border state during the American Civil War, I was working in an architectural firm in the Big Apple—a dream come true for many young European architects. I remember at that time to have visited an eye-opening retrospective on Shaker architecture and furniture titled “Shaker Design” held at the Whitney Museum of American Art, a beautiful yet brutalist style building designed by Bauhaus architect Marcel Breuer.

New York City in the 1980s

Being Swiss, when viewing the exhibition it seemed natural to me to internalize the 18th to mid-19th century Shaker aesthetic with the minimalist and stark attributes that were presented through photographs, iconographies, and objects, but mostly through furniture. The retrospective was exquisitely curated with items of unequal aesthetic refinement, and I contrasted the exhibited artifacts with, at that time, New York’s populist appetite for post-modern furniture, fabrics, ceramics, and glass; all consumable and ephemeral products created by the Memphis Group with a revival of Fornasetti Style.

This contrast between the ascetic experience of viewing the Shaker exhibit and the daily reality of visual kitsch was enhanced by a reminder that the Shakers’ fame was to “…aptly express the religious sect’s joy in work and its skill at transforming ordinary tools into extraordinary objects.”

Image 2: Main staircase in the Trustee’s building at Pleasant Hill, Kentucky

From the exhibition, I gained an admiration for the Shakers’ unconditional attention toward an economy of means, an insistence on a clear expression of function, a dedication to artisanship, a love of fabricating utilitarian objects, and the generosity in creating day-to-day modest yet beautiful clothing; all sheltered by an architecture of simplicity that communally honored the Kingdom of God.

The Shakers

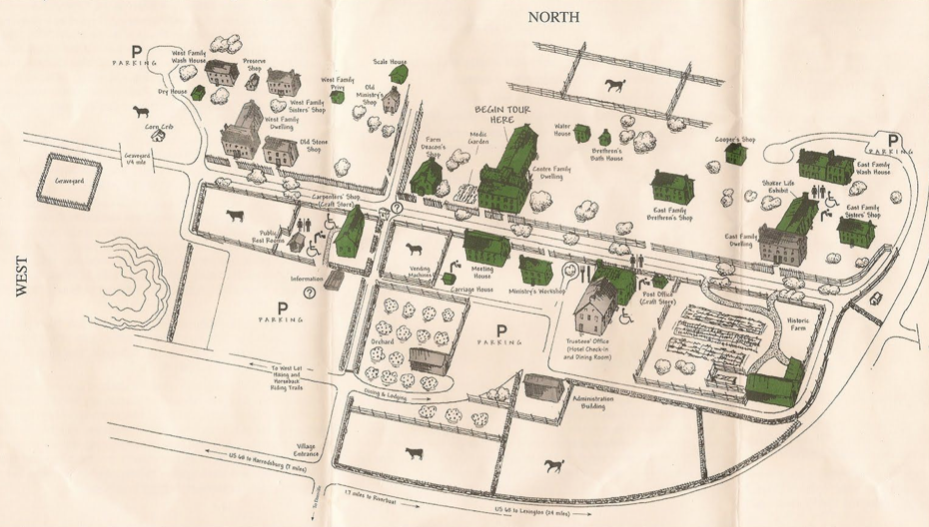

Image 3: Google image of the Shaker Village layout at Pleasant Hill, Kentucky

Image 3: Google image of the Shaker Village layout at Pleasant Hill, Kentucky

At that time, I knew about several European utopian societies that had left their homelands to settle in the colonies of the new world: the Anabaptist Swiss Amish and Dutch Mennonites in Pennsylvania; the German Harmonists in Indiana; and the English Quakers in Massachusetts to name but a few.

Yet, I was unaware of the impact that the Shakers—called the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Coming—had on America from their early arrival in 1776 from Great Britain to New York, Maine, Massachusetts and New Hampshire, eventually migrating to the state of Ohio and the town of South Union in Kentucky, their furthest outpost west of the Alleghenies. Central to the Shakers’ faith was their founding leader, called Mother Ann Lee, and her small group of followers who “came to believe that she embodied all the perfections of God in female form, and was revealed as the ‘second coming’ of Christ.”

Image 4: Top floor with cabinets at the West Family Dwelling at Pleasant Hill, Kentucky

Since then, and despite my countless visits to the Shaker Village over two decades living in Lexington, I continue to enjoy my pilgrimages to Pleasant Hill, especially that I now live in Virginia and within driving distance of Kentucky, which is closer than flying from California where I lived for seven years. Upon my return from a recent field trip to Pleasant Hill, I stumbled on a book by Thomas Merton titled Seeking Paradise: The Spirit of the Shakers. Merton was an American Trappist monk and prolific author living at the Abbey of Gethsemani near Bardstown, Kentucky. Merton writes about the Shakers:

Work was to be perfect, and a certain relative perfection was by all means within reach: the thing made had to be precisely what it was supposed to be. It had, so to speak, to fulfill its own vocation. The Shaker cabinetmaker enabled wood to respond to the “call” to become a chest, a table, a chair, a desk. “All things ought to be made accordingly to their order and use,” said Joseph Meacham. The work of the craftsman’s hands had to be and embodiment of “form.” The form had to be an expression of spiritual force.[1]

Image 5: Domestic objects found throughout the Shaker structures (author’s collection)

Question of being

Merton’s observations are striking and insightful in their pertinence, and beg the question about the act of creating; in particular about the “religious creativity of the Shakers’ communal craftsmanship.” The idea that any future object is imbued by a calling to become, and supposed to be, reminds me of a colleague’s many desk critiques with his sophomore students. He always inquired of his students why they continued to present their projects with typical and casual assertions.

I had, as an architecture professor, become equally accustomed to their words: I kind of want to do this, because I feel that, and I created this or that… While my colleague’s students hesitantly attempted to legitimize their creative authority, Art’s response remained the same, delivered in utter kindness: “Why is space-making about you, why is it not a response to something bigger than yourself?”

An architectural process

Key to his remarks is that for beginning students, design issues tend to be solely a matter of their own opinion, their way of seeing things, and this through their lens of inexperience. The relationship between solving a problem and architecture is still for many students in its infancy, in particular if their first year of a five-year architecture program neglects to introduce them to disciplinary fundamentals about the nature of architecture. Students in these early years often believe that artistic inspiration is the guiding force to establish an idea for a project.

This acquired habit, which may I say has become for many students a visual obsession without much meaning, weakens the architectural process to a point where a thoughtful investigation of their project—through a slow maturation by proposing options and iterations by massaging, calibrating, and adjusting concepts remains quasi absent.

Image 7: Main stair on the third floor with the celebration of an oculus, Trustee’s building, Pleasant Hill, Kentucky (author’s collection)

I believe that for today’s students to be successful as architects, there is a need to return to what the Shakers so eloquently understood when crafting their material culture, from objects to architecture, from usage to the intangible aspects of life. To solely respond through an Instagram culture of I like and I want fails to explore the richness to enable “wood to respond to the ‘call’ to become a chest, a table, a chair, a desk.” There is a balance between authorship and a calling to become which I believe both author Rainer Maria Rilke and architect Louis I. Kahn have eloquently stated.

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926)

“You ask whether your verses are any good. You ask me. You have asked others before this. You send them to magazines. You compare them with other poems, and you are upset when certain editors reject work. Now (since you have said you want my advice) I beg you to stop doing that sort of thing. You are looking outside, and that is what you should most avoid right now. No one can advise or help you – no one. There is only one thing you should do. Go into yourself. Find out the reason that commands you to write; see whether it has spread its roots into the very depths of your heart; confess to yourself whether you would have to die if you were forbidden to write. This most of all: ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night; must I write? Dig into yourself for a deep answer. And if this answer rings out I assent, if you meet this solemn question with a strong, simple “I must,” than build your life in accordance with this necessity; your whole life, even into its humblest and most indifferent hour, must become a sign and witness to this impulse.”

Louis I. Kahn (1901-1974)

“You say to a brick, ‘What do you want, brick?’ And brick says to you, ‘I like an arch.’ And you say to brick, ‘Look, I want one, too, but arches are expensive and I can use a concrete lintel.’ And then you say: ‘What do you think of that, brick?’ Brick says: ‘I like an arch.’”

[1] Merton, Thomas, Seeking Paradise: The Spirit of the Shakers, Orbis Books, MaryKnoll, 2003, New York p.78-79.

To view additional images of the Shaker Village at Pleasant Hill

Addendum (03.23.2020)

Rereading Peter Zumthor’s book Thinking Architecture (1998), I found the thoughts below on architecture pertinent to the content of this blog

Peter Zumthor (1943-)

“Good architecture should receive the human visitor, should enable him to experience it and live in it, but it should not constantly talk at him… Why, I often wonder, is the obvious but difficult so rarely tried? Why do we have so little confidence in the basic things architecture is made from: material, structure, construction, bearing and being borne, earth and sky, and confidence in spaces that are really allowed to be spaces – spaces whose enclosing walls and constituent materials, concavity, emptiness, light, air, order, receptivity and resonance are handled with respect and care?