Rainer Maria Rilke and architecture. I recently rekindled with two of my favorite books by German author Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926): Letters to a Young Poet and Auguste Rodin. While in college, I was introduced to other significant authors of German literature including Heinrich Boll, Berthold Brecht, Günter Grass, Thomas Mann, and Stefan Zweig, along with Swiss playwrights and novelists, Friedrich Dürrenmatt and Max Frish. Yet, Rilke’s writing has always left me with a sense of awe.

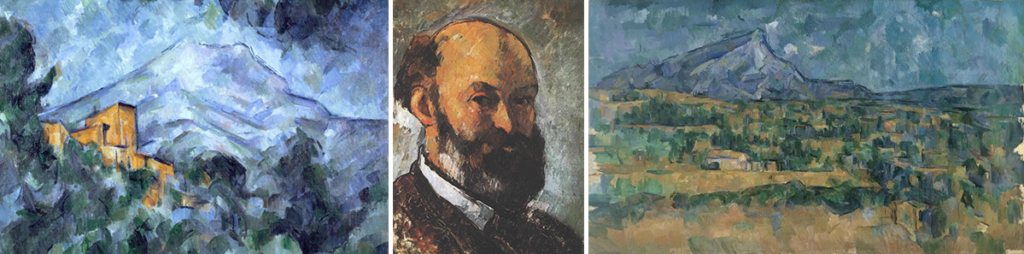

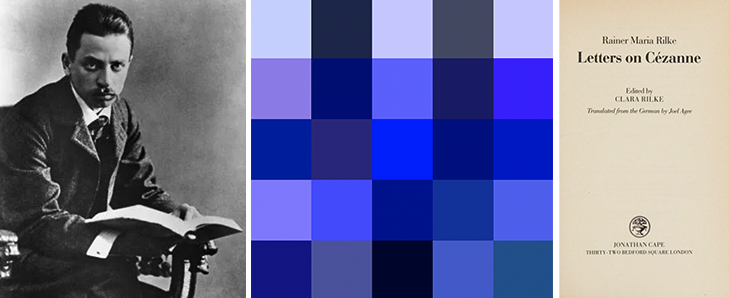

All these years later, I have a new favorite written by Rilke, Letters on Cézanne. As I read, I ponder and stumble through to the next page, because each word, sentence, and paragraph surprises me with the depth and poetic elegance of his writing—”giving visible life to the invisible.” I’m further slowed because I not only want to appreciate the full meaning of his writing, but I also have the habit (a bad one?) of reflecting on what I read and observe, and desperately seek to translate his words into my art form: architecture.

How do Rilke’s thoughts—in fact, any thoughts by anyone—apply to architecture? I have always learned by osmosis beyond the core questions I consistently pose to myself: what may I find within myself to create; how to find the calling of the project; how to infuse life in it; and why do my creations deserve to exist? Perhaps this approach to creating has defined my beliefs: That I favor re-inventing rather than inventing.

Rilke’s blues versus the taxonomy of the color of blue

The following analogy may seem far-fetched, but I want to associate Rilke’s qualification of the color blue with the interpretation of a door. You might ask yourself, what does he mean? Well, let me succinctly present my argument. In the introduction to Letters on Cézanne, Heinrich Wiegand Petzet refers to one of the letters where Rilke “speaks of the possibility of writing a monograph on the color blue.” He follows this with several variations of blues that Rilke writes about. Among them in no order:

Beginning with the pastels of Rosalba Carriera and the special blue of the eighteen century

Cézanne’s very unique blue

Completely supportless blue

The good conscience of these reds, and these blues

An ocean of cold… barely blue

Blue dove-gray

A glimmering of blond old warmth… an ancient Egyptian shadow-blue

Self-contained blue

Listening blue

Thunderstorm blue

Bourgeois cotton blue

Light cloudy bluishness

Densely quilted blue

Waxy blue

Wet dark blue

Juicy blue

Full of revolt, Blue, Blue, Blue (talking of Van Gogh)

Each of these variations of blue are pure Rilke and redefine the color with an extraordinary palette of senses, moods, and atmospheric metaphors. In fact, we very quickly recognize that the quality of Rilke’s blues have nothing to do with the technical taxonomy of blue in its 144 official shades. Some of which are alphabetically ordered:

Admiral blue

Aegean blue

Azure blue

Baby blue

Berry blue

Cerulean blue

Cobalt blue

Cyan blue

Denim blue

Electric blue

Indigo blue

Lapis blue

Light blue

Navy blue

Ocean blue

Peacock blue

Prussian blue

Sapphire blue

Slate blue

Sky blue

Spruce blue

Stone blue

Teal blue

Turquoise blue

Door versus the spatial concept of opening

Exploring the analogy between Rilke’s suggestions of a mood based on the color blue, and the taxonomy of multiple shades of blue, I wanted to compare how students learn about a door and its spatial conditions. As a student, I had first to learn about a door: the basic elements of a traditional door, which included a door jamb and its stop moldings and hinges; lock and hinge stiles; top, middle, and bottom rails; mullions and panels; and the bore hole that will receive the door handle.

Very quickly I recognized that a door was not only a physical barrier but would—if well executed—partake in a spatial practice that would become so much more meaningful. Moving from a door (i.e., the taxonomy of the color blue) to an architectural space that qualified the door as threshold, limit, enfilade, edge, passageway, and transition (i.e., Rilke’s metaphors of the color blue) is an important step in understanding Architecture.

I hope that student’s today—and practicing architects—carry Rilke’s sense of wonder into our own wonderful practice of building.