Architecture thesis, Part 3. There is a wonderful tradition at my current institution of holding weeklong thesis week’s presentations, a time when architecture students pin up their progress and get feedback from peers and faculty. During this time one or two faculty impart their wisdom regarding the day’s projects. These short addresses happens at the end of the day and are delivered in various formats depending on the faculty’s goals and interests.

These shared thoughts are diverse and typically look back critically at what was achieved, however they also may simply project how students might pursue new venues of research. Either way, key to the faculty presentations is that an intellectual dimension is imparted allowing students to transform many of their questions and struggles into a productive next thesis phase.

Many of my blogs focus on pedagogical issues and I have written two on the topic of thesis. In the first blog, I presented thoughts on the nature of what is a thesis; and this through a hierarchical five-point road map (argument, objective, problematic, methodology, and communication) to ensure an initial structure to anchor students in their design process. The second blog touched upon the stance students might have as they embark on a year-long self-directed research. In this second blog, I developed two foci topics: the need to want to say something and the necessity of being committed. The suggestions developed in each of the blogs should not be seen in isolation, especially that primary and secondary advisors remain key to a student’s success.

This third blog on the topic of thesis (yes, I realize that there seem to be endless words of wisdom that one can, and should, impart to students), will reflect on my previous observations and address, through an umbrella thinking, four additional points. Each of the four points found below are written to be understood as fundamental to any thesis activity, all the while suggesting a common attitude that I believe a student should have for a thesis—or any project—regardless of their topic, philosophical stance, or methodological road map.

I have organized the four points chronologically as they reflect my own autobiography as a lifelong learner, from my time as a student, to today as an educator and architect. Let us start with point 1.

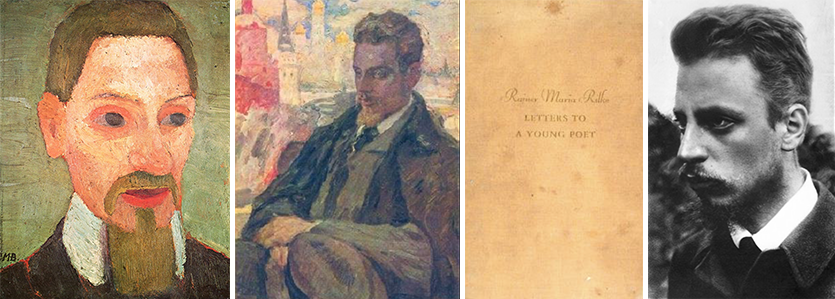

1. Rainer Maria Rilke

“After all, works of art are always the result of one’s having been in danger, of having gone through an experience all the way to the end, to where no one can go any further., The further one goes, the more private, the more personal, the more singular an experience becomes, and the thing one is making is, finally, the necessary, irrepressible, and, as nearly as possible, definite utterance of this singularity…”

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to Cézanne

My first point is anchored in my college years where German was for me the second foreign language to be learned—at least at school as I had learned English at home from my parents, and French at the French Lycée in Vienna, Austria. During my college years in Switzerland (I lived at that time in Fribourg which is a border city between French and German speaking cantons), I became familiar with significant German literature through authors such as Heinrich Boll, Berthold Brecht, Günter Grass, Thomas Mann, and Stefan Zweig, along with two Swiss playwrights and novelists, Friedrich Dürrenmatt and Max Frish.

Ironically, it is only during my foray to the United States to study at Cooper Union that I met the work of another German language giant, Rainer Maria Rilke. Cooper, at that time, was an intellectual heaven for me and the faculty—each in their own way—idiosyncratically treasured and promoted their persona by amplifying key books among their students.

For Raimund Abraham, who was my architecture studio professor, authors such as Maurice Blanchot (The Space of Literature), George Kubler (The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things), and Rainer Maria Rilke (Letters to a Young Poet) were ever-present during my tenure in 1985-86. Over the following years after graduation, I came to understand that each of these author’s were part of Raimund’s underpinning in his ontological search for an architecture that he called authentic.

On a side note, but an important one, when I started my teaching career, Cooper had stifled me at first as I was intimidated and intrigued, or simply had developed a blind admiration for the intellectual virtuosity of many of my faculty (Raimund, John Hedjuk, Robert Slutzky, and Dore Ashton), and to a certain extend Anthony Candido who I never had but from whom I learned a lot by simply seeing the impact he had on his students. As I am writing this blog, I am saddened that he passed away three days ago, a week after Anthony Vidler, whom I had at the IAUS.

I took to all of these authors that Raimund shared with us, but devoured Rilke’s book. I was humbled by a particular passage where Rilke discusses with his novice (Franz Xaver Kappus) about looking inside oneself; a moment of introspection where a “poet should feel, love, and seek truth in trying to understand and experience the world around him and engage the world of art.” If I substitute architecture for poetry, Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet gives me insight in “…what moves a writer [architect] to write [project]? What is the origin of his undertaking, and how does this origin determine the nature of his creativity?”

The passage above reads more completely:

“You ask whether your verses are any good. You ask me. You have asked others before this. You send them to magazines. You compare them with other poems, and you are upset when certain editors reject your work. Now (since you have said you want my advice) I beg you to stop doing that sort of thing. You are looking outside, and that is what you should most avoid right now. No one can advise or help you – no one.

There is only one thing you should do. Go into yourself. Find out the reason that commands you to write; see whether it has spread its roots into the very depths of your heart; confess to yourself whether you would have to die if you were forbidden to write.

This most of all: ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night; must I write? Dig into yourself for a deep answer. And if this answer rings out I assent, if you meet this solemn question with a strong, simple “I must,” than build your life in accordance with this necessity; your whole life, even into its humblest and most indifferent hour, must become a sign and witness to this impulse.”

Rereading this excerpt countless time and having shared it with generations of my students, I have come to the realization that at times, one’s best critic is oneself by daring to look critically at one’s work with simplicity and humility.

My question to any thesis student is how do you seek answers from within for your thesis?

2. The Shakers

“Actually without joy, it seems, in a constant rage, in conflict with every single one of his [Cézanne] paintings, none of which seemed to achieve what he considered too be the most indispensable thing.” … “To achieve the conviction and substantiality of things, a reality intensified and potentiated to the point of indestructibility by his experience of the object, this seemed to him to be the purpose of his innermost work;”

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to Cézanne

Growing up in Europe, I knew that the New World was built on ideas of colonialism and on the dreams of immigrants who imagined a better world for themselves, their families, and relatives. Crop failure, famine, job shortages, political repressions, and the desire to seek economic opportunities, were key to almost 12 million immigrants who arrived in the United States over 30 years prior to 1900.

Most of them were from Germany, Ireland, and England. Additionally, they represented religious migrations, for example, individuals of Jewish faith came from South America and Roman Catholics from England. They arrived at East Coast ports—in particular New York City (i.e., Ellis Island) which came to be nicknamed the “Golden Door,” before the city was coined “The Big Apple” in the 1920s. During that time, on the West Coast of the US, mainland Chinese ventured across the Pacific, lured by the Gold Rush.

Although I had a sense of the massive immigration to the New Continent due to religious persecution, I did not realize that immigrants from Europe had not only established themselves in major cities, but settled in rural enclaves in order to find sanctuaries to freely worship. It was only after I moved across the Atlantic to study in New York City, that I came to understand how some European utopian societies had settled in the colonies of the new world: the Puritans in Massachusetts, the Anabaptist Swiss Amish, and Dutch Mennonites in Pennsylvania; the German Harmonists in Indiana; and the English Quakers in Massachusetts, to name but a few.

During my first foray in teaching at the University of Kentucky—while also engaged in defining an architectural practice through my second loft renovation in the Big Apple—I discovered the world of the Shakers (United Society of Believers) who had settled a century ago near my new home, the city of Lexington, Kentucky. My newly acquired cultural appreciation and architectural interest in the Shakers stemmed primarily from the 1986 Shaker exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art – the famed brutalist building designed by German immigrant and Bauhaus professor Marcel Breuer in New York City.

In their search for refuge, the Shaker-settlers built enclaves that encapsulated beliefs through furniture (chairs and desks); stoves; built-in cupboards and drawers; kitchen furnishings and utensils; basketry; needlework; clothing; drawings; artifacts; and progressive agricultural inventions (wheelbarrows and farm implements); dwellings and meeting houses.

Their perfectionist craftsmanship that “emphasiz[ed] [modern] utility combined with simplicity and harmonious proportion” was a revelation for me aesthetically and tectonically as it reminded me of precepts learned during my studies in Switzerland: 1. a just principle of settlement in the landscape, 2. an economy of means in terms of building, 3. a lack of adornment in crafted objects, and 4. a model of life (for the Shakers that unfolded accordingly to religious beliefs).

The Shaker lifestyle was based on a celibate Christian one that was opposite of the ruling Victorian opulence current during the 19th century. For me, the Shakers created a community where superb utilitarian farm structures (they invented the circular dairy barn that was “widely recognized as an architectural icon and agricultural wonder”), communal dwellings organized by gender; workshops; and material culture had not only defined their identity but were designs deserving to be called architecture.

Years later, after numerous visits to Pleasant Hill and two Shaker settlements on the Northern seaborn (Hancock in Massachusetts, and Mount Lebanon in New York) among the 26 known Shaker communities, I discovered a book by Thomas Merton entitled Seeking Paradise: The Spirit of the Shakers. Merton was an American Trappist monk and prolific author living at the Abbey of Gethsemane near Bardstown, Kentucky. In his book, Merton writes about the Shakers:

“Work was to be perfect, and a certain relative perfection was by all means within reach: the thing made had to be precisely what it was supposed to be [bold by me]. It had, so to speak, to fulfill its own vocation. The Shaker cabinetmaker enabled wood to respond to the “call” to become a chest, a table, a chair, a desk. “All things ought to be made accordingly to their order and use,” said Joseph Meacham [famous Shaker cabinetmaker]. The work of the craftsman’s hands had to be and embodiment of “form.” The form had to be an expression of spiritual force.”

I had now been introduced to yet another way of seeing and observing.

My question to any thesis student is how do you find the inner nature of your thesis and what is it?

3. Michelangelo

My third point is based on an interpretation and reading of Bacchus, the god of wine. I remember the story that I am about to tell you as if it was yesterday. John Hejduk, dean at Cooper Union had, in his introduction to the year’s cohort of thesis students, gathered them to share something that was so profound to him, and for me nothing less than extraordinary and revelatory as a young architect.

At that time, slides were still common and, in a semi-darkened room tucked at the end of a long white corridor on the fourth floor of the Foundation Building, John presented to a devoted group of thesis students (yes, John had his unconditional followers), an image of Bacchus, the mythical Roman god of wine sculpted in a teetering pose suggestive of drunkenness. Of course, this was not what John wanted us to describe, although it was tempting as the artist had perfectly captured the state of inebriation that any College student had experienced at least once.

The image on the screen depicted a marble sculpture created by a architect, painter, poet, and sculptor Michelangelo (full name: Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (1475-1564)). There was no need to reflect on the greatness of the work of art in front of us. It was art in its most intense beauty.

In his typical and deep but melodious Bronx accent, John asked us what we saw on the screen. Between timid suggestions and authoritative proclamations, our answers were far from the poetry that was to unfold in front of our eyes.

In fact, I remember so many pointed answers from students that I was taken aback by their intellectual observational acuity when describing the perfect anatomical stance of Bacchus or the balanced composition of the figure; the placement of arms and particularly those of the legs in what should have been a perfect Greek contrapposto (counterpose) capturing the body in motion (in opposition to the composite pose that portrays stillness); perhaps the androgynous nature of the slender figure of the god; or the profundity of his rolling gaze towards the goblet; the wreath of grape and ivy leaves on his head similarly to Medusa’s living snakes; or simply the symbolism of the satyr at his side suggesting a companionship with Bacchus. And these were only a few of the observations that I remember.

We were far from truly observing the genius of Michelangelo. Minutes later, Hedjuk posed his question once again but this time it was followed by total silence—a long, very long moment of silence. The emptiness of our answers filled the room with a sense of weight. After what seemed an eternity, John stood up, and with a gentleness never seen before from a professor, asked: “don’t you see him B R E A T H E.”

This simple word was followed by the year’s pedagogical statement: “This is what we will learn; how to infuse life into inert material.” The projector was turned off, and John left the room swiftly with no further explanation.

My question to any thesis student is how can you infuse life into your thesis?

4. Daniel Humm

So far, I’ve posed questions around trusting one’s instincts; finding the true nature of one’s work; and infusing life into inert materials. I wish to conclude with a last thought to bring us full circle to what I believe is essential for any thesis. A set of positions that are fundamental and worthy of contributing creatively to the world.

Like many of us, I enjoy Netflix and its abundance of subject matter can literately glue any of us in front of our iPhones, computers, or jumbo TV screens. At the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, I discovered the series titled 7 Days Out that chronicled seven days prior to the start of a major event. Of the six episodes, Eleven Madison Park drew my attention when “the No. 1 restaurant in the world, staff and owners face a flurry of nerve-wracking challenges as they race to reopen after extensive renovations.”

The episode presents the seamless partnership between Swiss executive chef Daniel Humm and his associate owner Will Duidara, and the architects, contractors, chefs de cuisine and staff waiters. Needless to say, I was in heaven as two passions of mine, architecture and culinary experiences, came into unison as a work of art.

During the entire episode, I felt the constant pressure and the often in-the-moment leadership decisions that echo much of what any student or professional encounters days before a final review or when needing to hand to their clients the keys to their new home. In fact, what I love about architecture is encapsulated in Daniel’s comment that “everything we do is not to make it about us, it’s to enhance their [the patrons’] dining experience.” Fundamentally, the existence and identity of Daniel’s restaurant “is about the human connection.”

I am reminded how much food, dining, and the pleasure of gathering at home or at restaurants are about a meal, and part of world traditions. Christmas, Easter, Hanukah, Passover, Thanksgiving, Ramadan, and Yom Kippur are always accompanied by food.

Somewhere halfway through the episode, the camera focused on a tired Daniel, and what he had to say amazed me:

There are four fundamentals that define my cuisine:

- The dish has to be delicious

- The dish has to be beautiful

- Creativity: it’s important that every dish adds something to the dialogue of food today

- Its intention: it needs to make sense that this dish exists.

While the three first points seem mundane, yet fundamental to any chef worthy of leading a top restaurant, the fourth and last point has preoccupied me ever since I heard it. I simply cannot get this existential question out of my mind. The desire for a near perfect dining experience, the ambition of being the best, the luxury of providing exquisite service of a totally memorable and distinguished food, remains a high level of attenable excellence. But the pursuit of how and why a dish needs to make sense as something that should exist, seems out of this world.

My final question to any thesis student is how can you find a deep purpose to your thesis by asking the question: why does my thesis deserve to exist?

Conclusion

There is no one correct process to achieve excellence in architecture. But what is certain for me is that while students continue to refine and articulate their thesis argument over the next months, larger questions on the nature and purpose of a thesis might be worthwhile contemplating. They not only solidify a student’s identity as a humanist designer with a meaningful point of view, and a personal statement that is well argued, but also ease their transition to a professional world where the luxury of design thinking where people matter may no longer be the leitmotif of many architectural offices.