Carlo Scarpa, Venice entrance pavilion. Over the years, I have noticed that small, unobtrusive interventions are no longer discussed. Many of the intellectual riddles—especially in academia—now focus on the plethora of new, unexpected, bizarre, and even the fashionably ugly. If this is true, it is sad that what is now understood as architecture often no longer relates to how, in particular, small works of excellence contribute to the built environment.

“If you please, a small idea of mine: great work of art, always small size.” Carlo Scarpa -Academy lecture, Vienna 1976

Not that progress is suspicious, that new ideas are meaningless, nor that big – as in scale – is unwelcome. Yet I have come to appreciate small, discreet objects of delight and to marvel in front of what I believe to be an essential quality of an architecture worth discussing: One where the architect’s acumen is defined by a design concept which is, as the French say, juste; an end process resulting from thoughtful design thinking. One of the artifacts that comes to mind was designed by an Italian architect and is nothing less than an unpretentious object of delight.

Well, that might not be entirely true, as the architect in question is definitely not anonymous, but this project is discreet. I am speaking about the very well-known architect, Carlo Scarpa, and his entrance pavilion (1951-1952) which stands alone almost like a folly of a by gone era, on the grounds of the Giardini di Castello at the edge of the Biennale park in Venice. The pavilion originally served as an entrance gate and ticket booth (Biglietteria in Italian) for the rotating international art and architecture biennales. Today, the pavilion no longer serves its original function, but remains physically present—perhaps not it the best shape—to the delight of the afficionados of Scarpa’s oeuvre (Image 1).

As I write this blog, I am delighted to note that the pavilion is under restoration; perhaps god forbid, to serve as a gelateria!

Entrance ticket office gate/pavilion

During a recent trip to Venice with a group of students, I made a point to revisit the ticket booth and thought that my research could be the impetus to talk about design excellence that, at least for me, has relevance to three constituent elements regarding the act of building: a principle of settlement; a culture of construction, and an economy of means. These three universal themes are dear to me, especially since they are rooted in my time as a student in Switzerland. They are part of what I admire most about Swiss architecture and what makes great architecture timeless and separate from the fashionable.

What continues to draw me to this humble work of architecture is that it does not beg to be studied as a theoretical object. Perhaps this is because Scarpa left no theoretical position or writings regarding the pavilion. I cannot find much literature or actual drawings, plans, models, or construction documents on the structure’s history or its making. This is peculiar as many of Scarpa’s other works have a robust lineage of artifacts; documents that have been abundantly analyzed and discussed by scholars and architects such as Francesco Dal Co, George Dodds, Kenneth Frampton, and Robert McCarter.

I mention construction documents as, over the course of my study, and using current photographs of the in-process renovation, I was able to speculate on certain details and sequencing of assemblages of the canopy structure; in particular, the columns and beams. These will be further explored in this blog.

Thus, for me, the artifact seems open to interpretation based ‘merely’ on its physical presence, a study of which over the course of my research has greatly increased my understanding and admiration for the pavilion.

A principle of settlement

The pavilion was commissioned in 1952 by the General Secretary of the Venice Biennale for the XXVI Venice Art Biennale (the first international architecture Biennale took place in 1980 at the Arsenale with a catch-22 postmodern title: Strada Novissima installation at La Presenza del Passato (The Presence of the Past). Scarpa’s site strategy had the pavilion face—in a slightly offset manner—what used to be the grand avenue entrance, while at the same time be parallel to Viale Trento, a major artery where many of the international pavilions are located. (Image 3 and 4)

Scarpa’s intervention is extremely modest in scale; it is transparent and lightweight. This was in response to the municipality’s request to not impede the perspectival view between the grand avenue leading from the laguna that extends through the entrance gate (Scarpa’s pavilion) to the actual gardens of the Biennale. What is ingenious in the placement of his pavilion, is that Scarpa weaves two physical barriers—between a transparent metal railing and an opaque rough aggregate circular concrete base that extends to generous planters on either side—so that the pavilion and its boundaries are seamless. Remarkable in the overall strategy is that the physical and visual barriers happen below waist level while the literal and phenomenal transparency happens at eye level (Image 1 and 2).

Of note, while Scarpa designed other interventions on the grounds of the Biennale (the Art Book Pavilion (1950), the adjacent Italian Pavilion courtyard (1952), and the Venezuelan pavilion (1956)), the latter pavilion and entrance gateway are two of the few stand-alone projects in Scarpa’s oeuvre (Image 3). This is significant as his work was typically inserted into the city’s historic fabric, within or in addition to existing buildings combining “…an interaction among contexts where both old and new architecture claim sovereignty.”

It is also interesting to see how Scarpa references his own work for the pavilion; in particular the Italian pavilion courtyard canopy and planters (Image 5).

Unfolding of the plan

Having completed a photographic survey of the pavilion during my visit, I set out to sketch the plan of the booth, structure, and canopy upon return. While my initial sketches were imprecise, I learned that the simplicity of the pavilion was more complex in design than I had anticipated (what was I thinking as sophisticated and intentional use of geometry is key to Scarpa’s spatial experience and overall tectonics).

The series of iterative sketches (Images 7 – 9) are an attempt to understand the spatial geometry in a more traditional manner; one where sketching sets the seeds in one’s mind so that each new drawing builds upon the previous. Today, in a world where everything seems at one’s fingertips, the painful detective work that reflects a recherche patiente, ends up being extremely gratifying. Not only does one have a more holistic grasp on what is under scrutiny but, in this instance, the iterative process of sketching opened up several new avenues of research and discovery.

Through this process of trial and error, I came to a final conceptual diagram that I believe is a close approximation of the design of Scarpa’s entrance pavilion. Two geometrical forms work in tandem—the arc of the booth formed by a larger circle, and the canopy in the form of an almond that was off-center to the booth on two different compositional axis.

Vesica piscis

But there was more that made my day. In my last sketch (Image 6), I realized that I had encountered a familiar geometry called vesica piscis that is formed by the intersection of two equal circles (Image 12 sketch 8, Image 13). I had discussed this in a previous blog on Scarpa’s store in Bologna, but now discovered it featured at the entrance pavilion in the form of the canopy. This intrigued me to the point that I referred to web research, and with some difficulty found the only plan of the entrance pavilion and its immediate surroundings (it was not drawn by Scarpa). With this new information, I was able to confirm my intuition and drew the two circles of the canopy’s form in the shape of a vesica piscis (In blue, Image 4).

Culture of construction

For this second theme, let me start by analyzing the booth, followed by the canopy. A circular concrete plinth in the form of an oval—which later will be confirmed as an arc of a circle (Image 4)—forms the base of the pavilion. The base then curves beyond the booth to spatially define the entrance with planter boxes framing the entrance gateway to the right of the turnstile, while also defining the back edge of the pavilion.

Almost like a landscape intervention, the concrete planters and iron railings act as a physical barrier at the macro and micro scales. As architect Robert McCarter points out, the pavilion’s wall “straight, curved, thicker and thinner sections,” define spatial areas that interpret the notion of physical and visual edges; a key design strategy found in many of Scarpa’s works.

A. Ticket booth countertop

The scale of the pavilion is intimate, human centered, and crafted from a variety of materials. For example, in Venice the wooden oars—called by the Gondoliere remèr—used to propel their boats are made from a variety of types of wood. Originally crafted from a single piece of Ramin wood (a light, pale, straw-colored versatile hardwood that is native to Southeast Asia, and favored because of its light weight and rigidity), now days oars are composed of layered beech wood of various colors which allows for the fabrication of a curved blade called in Italian remo lamellare (Image 11).

Ceiling of the booth

At the pavilion, Scarpa echoes this technique of assemblage for the countertop, while also providing two circular countersunk pass-through coin trays. The rightful reference is unknown to me, but its use suggests an affinity with the fabrication of Venetian oars, and perhaps, because of the immediate vicinity to the Arsenale, is an acknowledgment of the specialized craftsmen working there or in nearby independent workshops during Venice’s maritime supremacy over the Mediterranean Sea. The gesture of the countertop is repeated on the other half of the ceiling almost if the counter and ceiling could form a uniform surface and suggest a large oar! (Image 12).

The metaphor of an elongated oar and its close association with Venice is what I call a culture of construction; one that Scarpa delighted in bringing to all of his work through ancestral gestures and his use of nearly forgotten construction techniques, such as the famous marmorino plaster that he used for luxurious wall surfaces in many of his interventions.

Door to the booth

The structure of the canopy

There is a unique quality in the definition of the pavilion, and this, for three reasons. First, there is a clarity of expression of the three constituent elements beyond the site strategy (Image 9): the solid base of the booth with its glass enclosure; the three columnar supports anchoring the canopy to the ground and to the beams; and the almond-shaped canopy that is attached to the columns and hovers asymmetrically over the booth and entrance turnstile (Image 14).

In a previous blog I described a trilogy between element, system, and structure, and I will use a similar approach to dissect the structure of the entrance pavilion now.

Element (first iteration)

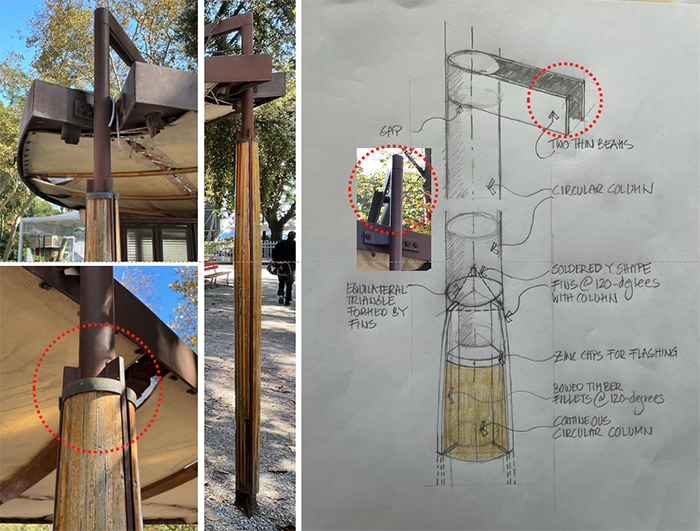

There are three elements in the form of columns that I initially assumed were defined by a central circular column on which three arched steel fins—in the form of a Y—were soldered in order to accommodate three bowed timber-fillet infills based on a 120-degree angle (2 times 60-degrees). At this point in my research, I am still unclear how the timber is fixed to the fins.

The three fins affixed to each column do not extend up to the three horizonal beams (Image 15, top left), thus leaving approximately 3 to 4 feet between beam and column assemblage. This gives the impression that the steel column emerges from a thicker timber column that swells slightly in the middle. The treatment of the joint (between column, fins, and timber) is reminiscent of a capital, although not serving that static function between column and horizontal support; and certainly, in this instance, having a different decorative intent. Finally, a small, yet prominent zinc cap serves as a drip edge preventing water from seeping into the top grain of the timber. All this seems to make sense in terms of tectonics and a desired expression for clarity (Image 15).

I mention the use of 60-degree angles for the fins for the simple reason that Scarpa used this geometry as a recurring motif. In the case of the Y-shaped steel fins, when joined at each of the three extremities they form an equilateral triangle whose proportions are balanced to create a geometry that is harmonious and an expression of unity.

Element (second iteration)

I was happy with my findings until a friend (Bill Blanski with whom I wrote a blog on Scarpa’s Gavina showroom in Bologna) sent me images of the pavilion partially dismantled due to the current renovation (the previous renovation was in 2004). In these photographs, I realized that my initial assumptions about the assemblage of the columns were incorrect and that another approach was used by Scarpa to express a more subtle means of joining the column to the fins. This was perhaps a more elegant solution due to the need of the pavilion to be assembled and disassembled.

As I continued my research, initially my findings revealed that the circular columns remain identical in assemblage to the U-shaped beam. Second, while having initially assumed that the column extended to the ground, the new photographs revealed that the column is much shorter and has three longitudinal slits. Third, these slits are made to accept three soldered fins in the form of a Y (as I initially believed) that constitute the main support for the hanging of the vesica shaped frame (I had initially thought the column provided the support) with its glass roof and suspended underside canvas.

Retrospectively, had I not focused on the ‘capital’ but looked closer at how the column touched the ground, I might have come more quickly to understand the assemblage of the round column, Y fins, timber infill, and triangular feet. However, I would have still been unable to understand the exact assemblage of the ‘capital’ without the new photographic information (Image 17).

System

Having already written about the elements and systems for the vertical support, now a quick word on those used for the horizonal support system. The extended circular columns shown here (Image 20) above the canopy and the tripartite beam system give the pavilion the necessary stability. Note that in Image 19 the canvas has been removed, while the bowed structure is still present with the wire glass. Image 20 shows only the vesica pisce frame.

Double skin of the canopy

Without going into much detail, I thought that it would be of interest to see the assembly between the vesica pisce frame, which is equidistant between eight bow trusses formed by an ingenious system of two wooden slats (almost a vesica pisce in its own right); the canvas hook attachments; and the tilted single laminated glass metal-mesh of the roof. Again, a superb expression of how materials are brought together. Of note, one must not forget the actual transparent and opaque ceiling materials above the booth (Image 12), thus providing three layers of roofing. Perhaps a shorter blog will come to investigate this layering and its purpose as it relates to the city of Venice! (Image 21)

Postscript 1

As I complete this blog, I am delighted to see Carlo Scarpa’s ticket office fully renovated courtesy of Cassina. Let me know what you all think of the restoration!

Postscript 2 (added 06. 11. 2025)

After completion of this blog, I was reminded of the modernist Berthold Lubetkin’s Tecton Group kiosk design (1935-1937) for the Dudley Zoological Gardens, just outside Birmingham, England. While far from the sophistication of Scarpa’s Biennale intervention, I found an affinity between both interventions.

Postscript 3 (added 06. 11. 2025)

The following sketches were done during my research to unravel the form of the entrance pavilion, as well as how to express my findings regarding the assemblage detail of the column.

Galleries of other works by Carlo Scarpa

Carlo Scarpa, Cemetery Brion Vega

Carlo Scarpa, Castelvecchio

Carlo Scarpa, Giardini

Carlo Scarpa, Gipsoteca

Carlo Scarpa, IAUV Architecture

Carlo Scarpa, Querini Stampalia

Carlo Scarpa, Olivetti Showroom

Carlo Scarpa, Banca Popolare

Carlo Scarpa, Venezuela Pavilion

Blogs

The following blogs reflect in-situ analysis of specific aspects of Carlo Scarpa‘s work. All images are part of the author’s collections

Carlo Scarpa Venice entrance pavilion

Carlo Scarpa Gavina Showroom in Bologna. Part 2

Carlo Scarpa Gavina Showroom in Bologna. Part 1

Carlo Scarpa and detailing

Carlo Scarpa Gipsoteca in Possagno, Italy