The need for disciplinary integration: Part 2. Design topics related to urban preservation have become one of my favorite themes when teaching second year architecture students. In my program briefs, I also tend to incorporate that projects be determined—to a certain extent—by a client’s functional needs, preoccupations, and desires, all the while having student projects reflect their creative ambitions.

I believe that the need to solve specific problems—social, cultural, aesthetic, functional, and constructive (the latter expressed in the students’ first forays into tackling basic cabinetwork detailing)—should be part of the client-architect dynamic. Recently, in a conversation about this, a master’s student noted that this client-architect relationship is equal to the sine qua non condition between architecture and site/context.

Metaphorically, this standpoint reminds me of the art of cinema, in particular films of Swedish director Ingrid Bergman, along with those of Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, where respectively the first “creates films that not only tell an art story, but are the story”; while the latter two, enfants-terribles of the French Nouvelle Vague, “capture not only real life, but are part of it.” These remind us of the necessary balance between artistic vision and the realities of life—perhaps expressed in architecture by recognizing the importance of function.

Architect and client

The pedagogical approach that emphasizes a client is not new to any architectural brief, although in my case, I ask students to define their client’s identity in more depth. The result is that students embark on a solid path of learning to think as an architect while exercising their talent in creating architecture, thus avoiding the promotion of architects as single key players in a complex professional world.

For me, this approach is particularly significant as it attempts to counter today’s cult of making attention-grabbing artifacts through garrulous gestures. Do not misread me, the necessity for individual creative and collective potential remains key for our métier, but only when inventiveness emphasizes the difficult and all-embracing definition of authenticity. The welcome architectural outcome allows a more holistic educational perspective that emphasizes a professional approach to solving problems, rather than dwelling on—although critical—the disciplinary aspects. While infinite ‘philosophical’ approaches define our art form, for me, projects designed with considerations of the client bring into question the boundaries between disciplines. Under these principles, students are invited to conduct open-minded conversations about integrative approaches that hopefully circumvent the need for readily available images and symbols that often hold architecture prisoner.

I am fully cognizant that this teaching strategy is deliberate. It ‘unlocks’ the student’s mind to see beyond the typical prompt where architecture is often practiced as the sole discipline in the overall design composition. For example, in the renovation project that includes five charettes, students are invited to define, and write, about the client’s personality (although the clients are often a reflection of the students themselves). Working with a client in mind (e.g., husband and wife and two adult children), requires students work at the perceptual and domestic scales, while interpreting the client’s wishes and needs, to result in a balanced approach (client-architect and architect-client).

Architecture as an integrative discipline

Defining client-architect connections should be experienced through the specificities of various disciplines including: architecture and landscape architecture (wall house project); architecture and interior design/preservation (loft renovation project); and industrial design and architecture (incorporated in the other program briefs).

While this approach is integral to a professional context, educational opportunities seem few and far between when thinking of a vision for seamless integration AND collaboration between different disciplines, especially between architecture and interior design. I have taught in interior design at my former institutions and understand the often-unarticulated resistance of architecture faculty to teach in that field. This often results in student architects who are obsessively focused on form making.

Yet, over the past years at my current institution, I have observed through the loft project, that architecture students have a genuine appreciation for an integrative client-architect approach. I believe this reflects a growing interest in being trained as well-rounded thinkers who respond in an interdependent way to solving various problems. The introduction of interior design thinking allows a natural broadening of education and enriches the topic of the intervention while offering a haptic definition of space. Something grand gestural projects rarely offer.

Overall, I believe that a common sense of reality reflects the creation of space as integral to the concerns of interior design. Such projects benefit student learning by introducing complexity through various disciplines, stressing that architecture becomes, once again, a collaborative endeavor, thus calling for students with a set of combined skills.

The nature of such projects offers students the ability to focus on what architecture can do, rather than a philosophical debate of what it is—the latter being equally important to a student’s education, but too often used as a subterfuge to avoid making architecture. Also, I currently teach sophomore year, and at the end of this year some students will question their commitment to architecture, because this is the year in which they were introduced to architecture for the first time and found it daunting after a year of ‘design thinking’ offered in the context of a liberal arts education. The loft renovation project, for example, lets them explore various facets of the profession, thus reinforcing the multiplicity of design skills needed to be a well-rounded professional in the 21st century!

The structuring of the exercise: the project and five charettes

Within this pedagogical context, for the first time students develop an ‘architectural’ project where their enjoyment is about learning about architecture. My sole strategy is to further the students’ conceptual and spatial thinking by introducing real-life issues. I would like to state that to simulate a real-world context has, over thirty plus years of teaching, rarely undermined student creativity. Real-life challenges demand design excellence and immerse students in thinking broadly about inspiration, imagination, and innovation.

This goal is accomplished through a loft renovation project that includes a series of charettes tailored to have students focus on design vignettes, such as the organization of a kitchen, casework as a spatial component of their loft (walk-in storage/closets), choice of art and furniture, and essays as a writing interlude. At the end of the project, I am pleased to say that these five topics are welcomed by students as part of common-sense, real-life constraints.

Why does such a project matter?

Reflecting on the final deliverables of the loft renovation, I believe that this approach is similar to an eco-system that points towards greater foundational topics encountered in their future professional lives: working at a territorial level by engaging the city and landscape, the politics of private and public places, a model of life regarding domestic living, decision making involving various stakeholders, and the ethics of social and cultural equity, to name a few.

Ironically, in many instances, students are pushed outside their comfort zone and no longer think about form and geometry. Students find new meaning in their project because there is a ‘real’ intent and purpose in creating space. Perhaps a first validation that architecture is part of a physical reality that they can have impact on; for both the users and for themselves as creative authors. It is a first answer to an important question: why does a project matter and does the design make sense? Intent and purpose come to the forefront of their design thinking rather than the obvious delight in making forms.

Loft renovation project

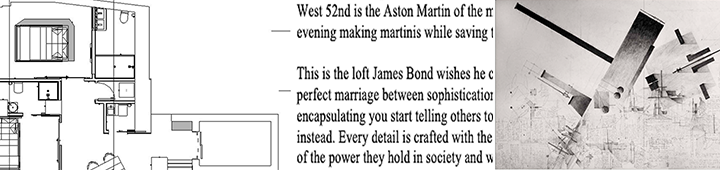

Over the past few years, I have enjoyed seeing students tackle the renovation of an urban loft as part of their second-year spring semester. For many students—after a short period of hesitation—the understanding of the topic becomes an architectural theme that integrates interior design. For me, there are two reasons for the project’s success:

First, because the program brief is tailored for creation within a set of programmatic and spatial constraints. The site strategy is confined within four walls, and, beyond the geometric edges of the apartment that are often terrifying limitations that students want to challenge, the footprint is accompanied by a structural column system. Thus, at first the students worry that there doesn’t seem much to hang their design hat on.

Second, as students familiarize themselves with the challenges, they come to appreciate the need for an integrative approach. They like doing the kitchen, and enjoy looking for art and furniture. The final project reflects their pride and success. Why is that, and what might be the reason for their sense of accomplishment?

Model of life

For the project to be successful, I invite students to think of what model of life they wish to translate within the existing space, creating a place that results from both the fictive client’s vision (program brief) and their own preconception of how one lives based on their personal experience of domesticity. For this to happen, students little by little clarify a model of life that builds on an initial understanding of the functional constraints leading to a thesis. Too often, at least in the early stages of a student’s design process, functional requirements are translated in form without a sense of a program, aka a big idea about the loft.

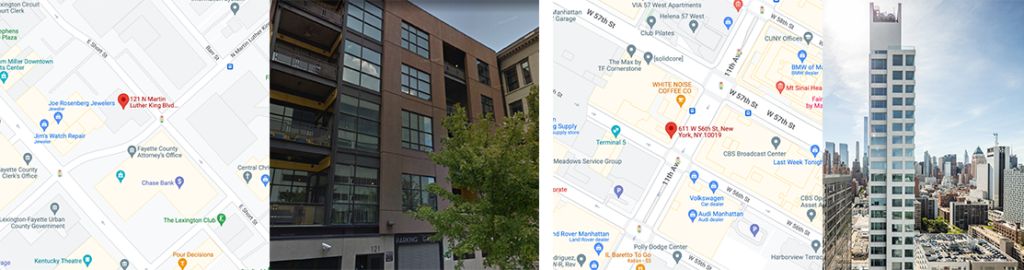

Site

For many students in second year, site and context are abstract at the beginning of their studies. In the loft project, I not only choose an existing site, but build upon an existing renovation. Students are given a drawing of the shell of the apartment and have two weeks to develop an initial scheme. Thereafter, an actual plan of a renovation in the building is shared and discussed among the group, followed by a field trip to visit the loft. For the Lexington site, students visit the existing renovated loft and interact with the owners. Many design features can be contextualized, revealed, and measured against their own project. Students can compare by contrasting their designs with the existing built project. Physical attributes of the existing loft allow for an appreciation of space as a haptic experience and is key to understanding their proposed layouts. This was an ideal condition pre pandemic and I look forward to expanding this experience to other cities.

Functions: blog

I remember Raimund Abraham insisting that use was key to architecture; thus in the renovation project, students are presented with several domestic functions including bedrooms, bathrooms, kitchen, dining room, living room, and a library. These functions are always identical to the built renovation.

Process: blog

To achieve a successful architecture project, process is essential as it expresses the visual sequence of thinking that leads from one idea to another. Process can be done through a multitude of techniques from diagraming, sketching, and conceptualizing to hard lining a project.

Charette 1: Writing interludes: syllabus and blog

Three interludes offer students to explore the written word as another important method to express architectural ideas.

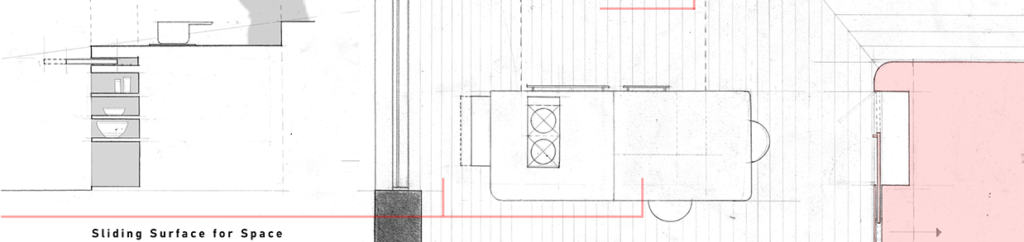

Charette 2: Kitchen design: syllabus and artifacts

Offered as a moment of deeper reflection into a particular spatial condition, the design of a kitchen allows students to tackle dimensioning, work sequence, kitchen triangle, and common-sense gestures surrounding one of the most ancestral human acts: cooking.

Charette 3: Cabinetwork: syllabus and blog

Engages students to think constructively through the detailing of cabinetwork.

Charette 4: Art and furniture: art syllabus and furniture syllabus and blog

Charette 5: Spatial exercise: blog and artifacts

Conclusion

There are countless ways to learn about architecture, but the loft project, year after year, shows the sensitivity, curiosity, and creativity students have when confronted with increased complexity. The integrative aspects offer them a first immersion into the meaning of architecture at a domestic scale, while dwelling on seemingly more mundane architectural aspects, including those which architects have given up to other art forms, and which may be reclaimed as part of their own portfolio. Architectural education in the 21st century demands a return to the fundamentals of how to practice, and I believe that having students immersed early on in working within multiple disciplines can only enrich their creative output to the betterment of the existing and new environment.

Related blogs

Final architecture presentations drawings

The need for disciplinary integration. Part 1