Giuseppe Terragni, Casa Rustici. After visiting the Casa Lavezzari, followed by a delectable apricot-filled croissant and Italian espresso at a local Bar-Tabacchi (coffee bar that sells tobacco and stamps in addition to drinks of all sorts), I located a nearby metro entrance and rode to the Domodossola station in the western part of Milan.

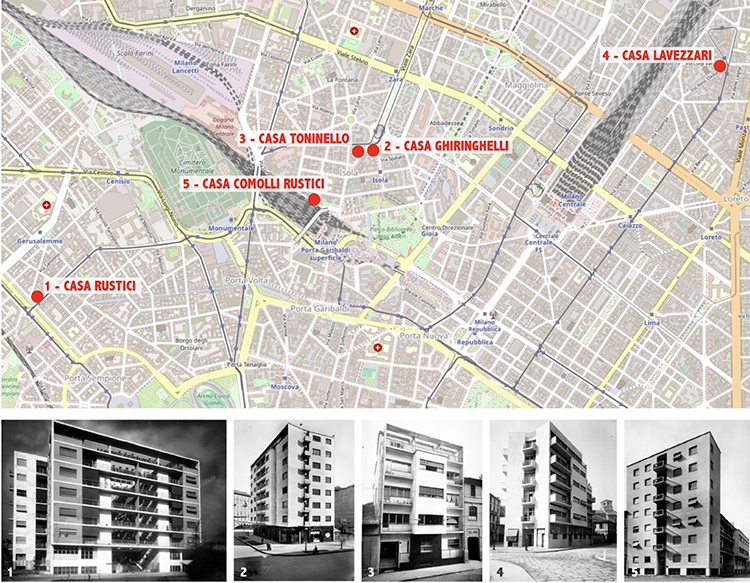

A short walk brought me to the much-anticipated Casa Rustici (1933-1935), the second of Terragni’s multistory residential buildings (he built three others in Milan: Casa Ghiringhelli, Casa Toninello, and Casa Comolli Rustici) that I had promised myself to visit; a long-anticipated journey, which was almost 30 years in the making. I was excited to finally meet the building in person (Image, above).

Significance of Casa Rustici

One always knows when the building is of significance, but in this case, at the entrance of Casa Rustici, a panel has the following description:

“Built between 1933 and 1935 to a design by Pietro Lingeri and Giuseppe Terragni, Casa Rustici is one of the finest examples of rationalist architecture in Milan. Originally intended as a block of rented apartments, it consists of two distinct units running parallel to each other and at right angles to Corso Sempione. The main street front features a series of balcony-style walkways connecting the two volumes, simulating a traditional façade and creating a sense of continuity along the street.

Each residential block has its own stairs, reached by a communal raised area above the entrance. The frontage has alternating bands of marble and plasterwork blocks that highlight the budling’s crisscross pattern of beams and pillars. Adjoining the northern block is a marble-clad tower containing living space with windows on three sides. The penthouse floor contains a one-family residence with garden, organized as two separate spaces connected by a suspended walkway.”

As a post script to the above text, while researching the building, I learned that as a result of the unique siting, specifically the visual access to the courtyard, “this innovation [principle of settlement], was regarded with suspicion by the municipal bureaucracy, which rejected the project nine times, thus delaying its construction.” A reminder to fight for what makes common sense, even if it goes against accepted traditions!

Site strategy

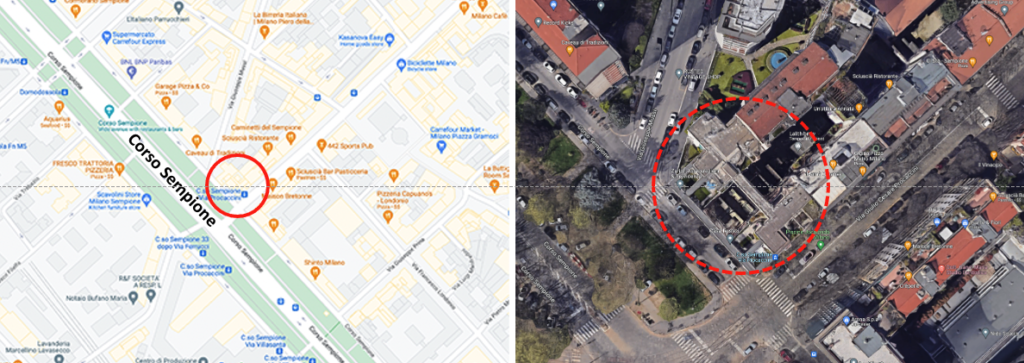

Casa Rustici was designed collaboratively by Pietro Lingeri and Giuseppe Terragni, and is located on a trapezoidal-shaped plot framed by Via Mussi and Via Procaccini (although not as acute a site as that of Casa Lavezzari). Its main façade faces Corso Sempione, a typical broad tree-lined boulevard constructed during the Napoleonic era (Image 2, above). This Parisian-style road connects Terragni’s housing complex to Castello Sforzesco—where I found nearby a wonderful restaurant (Taverna dei Golosi) and treated myself to a Milanese Risotto and Aperol. The road extends to the historic city center with its Galleria Umberto Emanuele, famous Duomo, and luxury shopping area surrounding Via Montenapoleone.

A New York precedence

While I say facing the street, I do not mean that Casa Rustici showcases a typical closed street façade. Instead, its overall strategy reminds me of SOM’s Lever House in New York City, a design which broke the urban frontage by shifting the 22-floor rectangle perpendicular to Park Avenue—a gesture among other seminal moves that gave the Lever House “universal recognition of its pivotal importance to American architecture.”

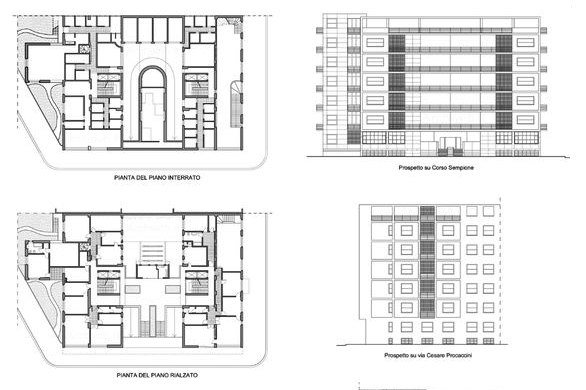

Casa Rustici’s comparable gesture is modest in height—ground level with offices and garage, with six stories above and a villa-like penthouse divided in two parts joined by a walkway. But overall, Terragni’s strategy is innovative and reinterprets the typical Milanese corner and façade treatment of the mid 1930s. Interestingly, when locating Casa Rustici within the surrounding buildings, Google maps shows that the building continues the existing morphology of the city block, although it provides a new identity through the treatment of the front façade (Image 3, above, (left and middle right with courtyard in yellow and orange).

Entrance sequence

Similar to Casa Lavezzari, Terragni’s urban strategy with Casa Rustici is to develop two elongated rectangular masses, where, because of the generous distance between the two parallel arms, an internal courtyard is created, allowing the apartment blocks to enjoy natural cross ventilation and enhanced access to light. The ‘end’, or front façade on Corso Sempione, ties the two bodies into one, but not through a typical opaque façade. It is done through a series of suspended walkway-balconies, creating a syntax that joins both apartment blocks.

The front entrance becomes evident and is developed at the scale of the city in a monumental manner tiered on the lower two levels. After passing a foreboding high entrance grill, one enters beneath a permeable facade created by superimposed suspended walkway-balconies. From there, one is led to a symmetrically positioned stair and an upper open-air mezzanine that forms the entrance to both apartment complexes. The entrance sequence and landing are covered with a concrete beam canopy into which brick glass is inserted. Everything reinforces the circulation path, while offering Piranesian views towards the upper levels (Image 4, above).

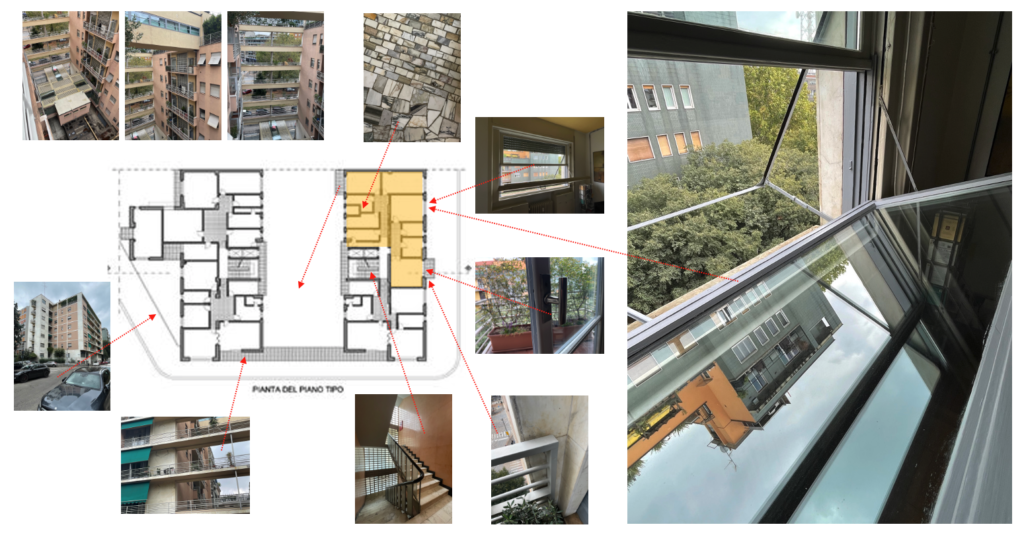

My lucky day

I owe much of my internal spatial experience (after the main entrance) to the generosity of a couple who had returned home on their bicycles. They saw me trying to immortalize the monumental entrance sequence by photographing through the main gateway. They kindly invited me to enter and see first-hand the courtyard. After conveying my gratitude and admiration for the building, lo and behold, they invited me to their upper-level apartment facing Via Giulia Cesare Procaccini, a street named after the Italian painter and sculptor of the early Baroque era in Milan (Image 6, below, apartment highlighted in yellow).

Tucked all three into a small elevator—which featured the original hardware, burl wood paneling, and interior manual double doors, all accompanied by a gentle grinding noise—we exited on the couple’s floor. To my right was a majestic stairwell bathed in continuous light by means of a floor-to-ceiling glass brick wall facing the interior courtyard. I am always enamored by staircases and in particular stairwells—stair house/stair room in German speaking countries—that have been so beautifully thought out as spaces in their own right. Casa Rustici’s stairwell is one of these.

Stairwell

The simplicity of expression of the stair is accomplished through enduring materials; white marble for the steps, ochre-colored brown stone for the walls (similar to the lateral northern outside plaster walls, with an interior texture reminiscent of Carlo Scarpa’s revival of Marmorino wall surfaces that exhort elegance with a glossiness and transparency). Additional materials are black stone for the wall stringers, frosted glass between gray painted metal balusters, and a continuous glossy wood handrail that snakes elegantly up each level. Within this space, there are a number of key details that captured my attention and which I would like to highlight (Image 7, above).

First, there are no newel posts at the landings nor in the middle of the flight of stairs as is traditionally done to offer primary structural support. This strategy shifts the structural integrity to the balusters (Terragni’s use of industrial construction contributes to the structure of the balustrade). The resulting spatial effect is that the stair appears to have a visual lightness as you progress, while each landing opens to the gap between flights.

Detailing of the stairwell

Opting to accentuate the verticality of the entire stairwell, Terragni further inserts thick vertical frosted glass panels between the balusters. These are positioned at the nose of the step and are fastened to the string. All in an elegant manner. This allows transparency, while giving a refined degree of enclosure. In addition, these glass inserts are asymmetrically positioned between balusters, thus offering a visual impression of shifting, adding a dynamic quality for anyone ascending or descending the stairs. Also noteworthy is that the brick glass continues at each landing, while a band is inserted in the brick glass to designate the level of the floor, contrary to most stairwell designs (Image 8, below).

The overall atmosphere of the stairwell is one of serenity, and the quality of reflective light on all surfaces is magic. Perhaps, in this instance for the design of the staircase, Terragni interprets the artistic chiaroscuro technique found in painting by working with light materials and the shadows cast by the risers, all in conjunction with the dark border, the balusters, and the wooden handrail. The effect of a gradation of light and dark is stunning, yet so simple and seemingly effortless. It is said that Terragni expressed a fondness for historical interpretations as a “continuity with the past and the values of tradition, [all in an effort] to dialogue with modernity.” With this thought in mind, conjectural interpretation is allowed as I am an architect and not a historian.

As a side note, while conducting research on Terragni’s Casa Lavezzari, I discovered an interior photograph of the main stairwell. While I did not have the opportunity to enter the building during my visit, after experiencing first-hand the stairwell in Casa Rustici, I recognize a similarity apart from the distinguishing triangular shape of the stairwell (Image 9 and 10, above).

The apartment

In the apartment I was fortunate to visit at Casa Rustici, the husband’s profession required a separate office; thus, the couple purchased two adjacent apartments and combined them to form a unified living-professional quarter (Image 6 and 10, plan in yellow). While the choice of furniture, designer lighting, and the bedroom’s new built-in hanging casework (beautifully designed to not touch the floor), reflects a simple yet elegant mode of living, there was throughout my visit, a great reverence from the owners to maintain Terragni’s original features. Existing flooring, wall color schemes, and bathroom amenities gave a sense of what modernity meant in the 1930s.

In today’s world, where particular refinements of kitchens and bathrooms are almost designed to an extreme—often leading to gimmicky design strategies and unnecessary encumbering houseware—the simplicity and economy of means offered in this apartment seems, retrospectively, state of the art for the 1930s. I remember decades ago seeing in a rundown Parisian hotel, signs proudly announcing “Eau et Gaz a tous les étages,” (water and gas on each floor). We have come a long way from that moment of providing basic domestic amenities designed to equalize society through access to electricity, gas, running water, and private kitchens and bathrooms within each apartment (Image 11, below)

While visiting Giuseppe Terragni’s Casa Rustici, I was mostly drawn to the details including the ergonomic doorhandles and the complex window contraption that allowed a large glass panel to slide down and move within the room to offer a new relationship between inside and outside.

Conclusion

After my visit to Terragni’s Casa Lavezzari and Casa Rustici, I have a renewed interest in pursuing research on a type of architecture that is less dogmatic, and more historically sensitive and linguistically progressive for its time, while remaining vulnerable in its lack of perfection (i.e., the rather traditional organization of the apartments). I will admit that beyond these recently visited apartment complexes, I have never had the occasion to enter any of Terragni’s work to experience their spatial quality.

Books, photos, and architectural systems of notations continue to tempt my curiosity. Yet each time I visit his work in person, I gain a renewed appreciation for Giuseppe Terragni’s oeuvre; one that I hope to emulate in my own spatial forays as an architect.

Additional galleries and blogs related to Giuseppe Terragni’s work

Galleries

Giuseppe Terragni, Como

Giuseppe Terragni, Milan

Blogs

The following blogs reflect in-situ analysis of specific aspects of Giuseppe Terragni‘s work. All images are part of the author’s collections

Giuseppe Terragni, Casa Lavezzari