Giuseppe Terragni, Casa Lavezzari. I feel conversant with key projects of Italian architect Giuseppe Terragni (1904-1943), particularly those built in Como; a provincial city on Lake Como just an hour north by train from Milan. The Casa del Fascio (1932), Sant’Elia nursery (1937), Novocomum (1929), and the Casa Giuliani-Frigerio (1939)—the latter two being apartment projects—are emblematic of Terragni’s oeuvre and continue to be observed, researched, and used since his early death at the age of thirty-nine.

Giuseppe Terragni

Much scholarship has been published about the prowess of these designs, yet each time I revisit them, I remain in awe at Terragni’s ability to combine strong architectural tectonics with an ever-present meaning: they “come together with both subtlety and consequence.” All of this about buildings that have caused endless debates. His architecture lies between the fascist expression and classic Italian modernism that is commonly represented as the best rationalist architecture of the 1930s. Among the aforementioned projects, the Sant’Elia nursery school remains, hands-down, my favorite of his built work.

My admiration for this particular building lies in the social program that offers a learning environment for infants, while fostering a new out of the home place that provided indispensable services for the daily users; basic necessities that most of these infants and children had not been regularly exposed to in the sanctuary of their parents’ home. Terragni offered generous spaces bathed in light and filled with democratic pedagogical opportunities, in addition to amenities such as thermal comfort, regular meals, and access to daily hygiene—all centered around the well-being of the infants and kids.

Milan, Italy

There are two other housing projects by Terragni—both in partnership with architect Pietro Lingeri (1894-1968)—that I had always wanted to visit in the city of Milan. Fortunately, during a recent trip to Europe, I had some time to seek them out and was able to compare and contrast my understanding of them with an actual site visit. I had written a blog about the often-dichotomous understanding between what I was taught about a building with those impressions left by any first site visit to the same building. Once again, I was unsurprised to see this in real-life. In short, my two Milanese experiences made my day.

Casa Lavezzari. Milan (1934-1935)

I took a 30-minute stroll north from my hotel to the Casa Lavezzari located near Milan’s Stazione Centrale. Located in what I consider a working-class neighborhood (called NoLo for the district north of Loreto) Casa Lavezzari appeared to my left upon arrival, facing piazza Morbegno. To be spatially precise, piazza Morbegno is more reminiscent of a small public square compared to the title bestowed on the only piazza in Venice, namely Piazza San Marco, called Europe’s reading room by Napoleon Bonaparte.

Upon my approach to the building, I was reminded that in so many European cities, banal, good, and excellent architecture all often remain anonymous, almost unnoticed if not carefully scrutinized by an educated eye. Architecture is integral to the daily lives of citizens and rarely elevated to the status symbol expressed by the singularity and object-oriented monuments that architect’s typically build for themselves. Casa Lavezzari (1934-35) is one of these moments that unambiguously contribute to the urban fabric in a humble manner, yet it was designed by a famous architect; a rationalist architect who was able to make a discrete mark among the typical 19th century morphology of Milan’s urban fabric.

Urban strategy

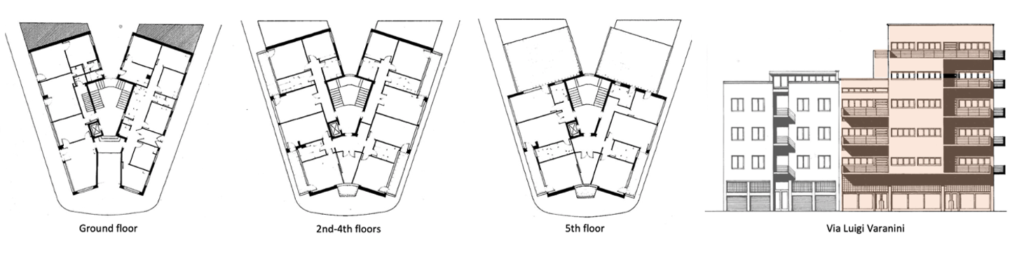

The massing of the building appeared much smaller in scale than I had anticipated—often a disappointing feature of most buildings after knowing about them only through books. The symmetry of the front facade of the apartment complex (27 feet only) faces the piazza at an acute angle, presenting a face of commanding authority and visual stature. Simultaneously, Terragni’s design ties together the symmetrical trapezoidal-shaped site with two distinct apartment block wings paralleling the streets, the Via Nino Oxilia and Via Luigi Varanini. The volume at this intersection subtly echoes the general massing of the adjacent building (Image 1, above left).

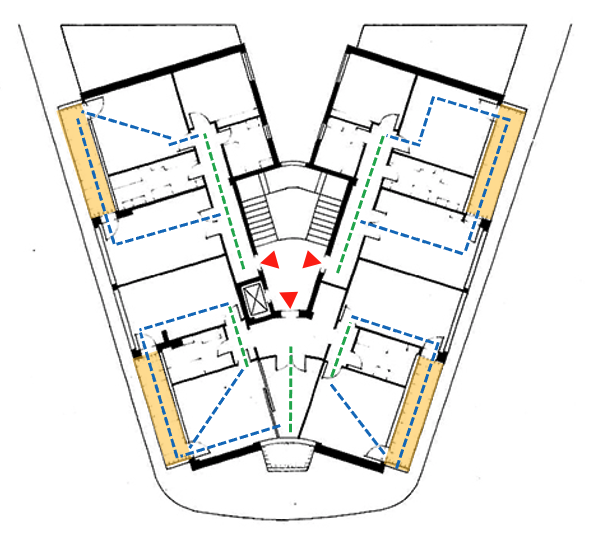

The original five-story structure of the Casa Lavezzari—disregarding the unfortunate 1950s addition of a penthouse apartment (Image 3, below middle), sits on a two-story modern plinth of shops and workshops (currently a bar, beauty parlor, and pharmacy), with an upper façade treatment typical of Terragni’s work. Each of the street façades build on a vertical datum plane on which Terragni anchors a protruding thickness that consists of an opaque frame which incorporates two horizontal windows per floor (a ribbon window typical of modern facades). These are extended on both sides with balconies whose balustrades form a horizontal L so that the overall symmetrical composition (mass and balconies) frames each street (Image 3, below).

Window treatment

This formal strategy of handling the protrusions that form the thickness of the façade—as both an addition and subtraction within the projecting mass—reminds me of similar moves found in the Casa del Fascio and Casa Giuliani Frigerio (Image 4, below). The overall tectonic treatment of the window openings of the Casa Lavezzari are in direct opposition to those facades found along the neighborhood streets.

These typically consist of narrow vertical windows with small stuck-on balconies, all framed by stylistic attributes of neo-classical architecture. And yet, upon closer examination during my site visit, and when analyzing Terragni’s elevations in drawing, one sees a subtle interpretation of the building’s direct neighbor, especially the adjacent one on Via Nino Oxilia, where in Terragni’s hands the horizontal repetition of vertical windows becomes a smaller version of Le Corbusier’s ribbon window (Elevation in Image 2, above).

Noteworthy are also what seem to be generous ceiling heights for each apartment (interpreted through the reading of the facades and the 22 steps shown in plan of the main stairwell, all suggesting a floor-to-floor height of 11 feet with interior ceilings of 10’-6”), thus Terragni’s introduction—in addition to providing ample light, air, and ventilation for the room through the balconies wall-to-wall window and door openings—of a horizontal glass block clerestory band that faces the balcony and allows light to penetrate at the precise juncture between façade and ceiling.

Light

I believe that this strategy is particularly creative within any urban context that is formed by the close proximity of a building facing opposite street facades. This move transforms the atmosphere of an entire room by the addition of slender horizontal windows. I can only imagine the interior wall dematerializing through these various devices, thus giving each room unprecedented spatial qualities; a feeling enhanced by knowledge that the typical windows of nearby apartment complexes are simply decorated holes, offering light only near the aperture.

Upon a second look, many of the clerestory windows are concealed by later additions of sun shading devices, thus revealing the inhabitants’ need to protect rooms on the south facing side of Via Nino Oxilia. These shades were not present in the 1930s photographs or elevation renderings, nor visible today on the north facing façade on Via Luigi Varanini, which makes sense due to the living room orientation (Image 1, 3 and 4 above). This is an appropriate reminder that there is always a fine balance between the architect’s formal intention and of those domestic and daily necessities for the inhabitants (i.e., providing shade from south light to avoid overheating).

Front facade

Returning full circle to the short façade facing piazza Morbegno, the composition reinforces the end of the two wings. It is austere and modestly treated, yet powerful with its ship-like prow, revealing in an almost sectional manner the collision of the two street sides culminating in the front façade balcony “from which to ‘see’ the square.” The central protruding balconies on each floor hint at a room, which in plan is tripoidal and minuscule and whose function is an entrance foyer or antechamber to the south living rooms. More importantly, the scale of the balconies seems to be a clin d’oeil to those across the street (Image 5 below, right).

Lausanne, Jacques Favarger

As much as I came to admire Terragni’s Casa Lavezzari—especially after my visit—I was reminded of another of my favorite social housing blocks. This one by Swiss architect Jacques Favarger (1889-1967) located at the rue d’Etraz in Lausanne, Switzerland. As a young architect, I was thrilled to live in one of the smallest apartments of one of his buildings, but it was mostly the facades that impressed me; in particular, his visual treatment of a number of degrees of porosities between full and empty spaces, transparencies and closures. Of course, the alternating façade treatments give a new spatiality to the interior, especially when the balconies serve a double function as balcony and as an outside corridor linking interior spaces (Image 6 and 7 below).

All of these Lausanne features are similar to Terragni’s Casa Lavezzari; spatial strategies that distance themselves formally and functionally from the Novecento Italian style so prevalent in Milan’s architectural facades during the 1930s (Image 8, below).

My next site visit was to Terragni’s Casa Rustici. Stay tuned.

Additional galleries and blogs related to Giuseppe Terragni’s work

Galleries

Giuseppe Terragni, Como

Giuseppe Terragni, Milan

Blogs

The following blogs reflect in-situ analysis of specific aspects of Giuseppe Terragni‘s work. All images are part of the author’s collections

Giuseppe Terragni, Casa Rustici

Wonderful!

Dear Antonino,

Thank you for reading my most recent blog. Very much appreciate.

Thank you for this article and your drawings and observations on casa Lavezzari.

Dear friend, Thank you for your encouraging comments. I fell in love with this magnificent yet modest apartment building. Amities, Henri