Interview about architecture. The following interview was conducted over zoom on September 6, 2023, with Berk Oral, a former second-year student, and friend. He is currently studying in Boston as part of his fourth year off-campus semester and will return to campus to complete his year-long thesis during the Academic year 2024-25. The interview is part of a requirement at the CDR Payette OpenLab Boston Studio, where students choose to interview professionals for their Professional Practice course. Other courses during the semester are the integrative studio and fabrication.

Berk kindly transcribed the oral interview, and I provide some minor corrections to have the reader move more clearly from idea to idea.

Interview with Henri T. de Hahn – Professor, Virginia Tech

Berk: What is the role of an architect and how would you define being an architect?

Henri: I believe an architect’s primary mission is to enhance the lives of their clients. This involves more than simply fulfilling their exact requests; it’s about interpreting their dreams and aspirations. With your talent, you transform their verbal and visual ideas into physical spaces. The ultimate goal is to improve their lives, whether it’s a home or a museum. I often say that architects have a unique opportunity to model life itself. We take the clients’ desires, blend them with our own perspectives, structure them, and give them tangible form. Architecture, to me, is a profoundly social and cultural endeavor that goes beyond mere form-making. It extends far beyond personal satisfaction. While it’s inherently a creative field, it’s fundamentally about serving others to enhance their lives.

Berk: Would you agree that when presenting a design to a client, it’s not just about merging their vision with ours but also elevating it, perhaps introducing them to something new, something they couldn’t envision on their own?

Henri: Absolutely, you’ve captured it well. I’d like to make a distinction here between architecture as a discipline and architecture as a profession. Historians and some colleagues often focus on the discipline of architecture, which is truly fascinating. However, there’s also the practical aspect of architecture as a profession in service to clients. In the United States, many clients may not fully comprehend what architecture entails or even understand the term itself.

I recall a humorous instance where someone mistakenly referred to it as “agriculture” instead of architecture. It’s worth noting that in some countries, like in your country, Turkey, there’s a more profound appreciation for architecture due to the rich array of architectural styles. From the Medieval Age to the Renaissance, or to Islamic architecture such as mosques, there’s a vibrant visual and cultural mix that permeates daily life. However, I would say that, in general, many clients, as you rightly pointed out, might be considered somewhat architectural “illiterates” because they haven’t been deeply immersed in the world of architecture. Often, we take pride in our successful students, but it’s equally important to equip them with the skills to interact effectively with clients.

Returning to your question, yes, clients typically come with certain expectations. However, it’s our duty as architects to guide them toward a more enlightened perspective. I’ve been fortunate to work with clients who, despite not being architects themselves, possess a rich cultural background and clear preferences. Their input has been invaluable, helping me make informed design decisions. I recall a project where a client emphasized the need for specific storage spaces, which significantly influenced my creative process.

I used to say, give me an elevator shaft in New York and I know how to deal with that pressure, but you give me a site in the middle of nowhere and I am lost. In essence, I’m an architect who thrives on pressure and client input. While I have my distinct architectural style and principles, I’m always ready to adapt and tailor my approach to meet the unique needs of each client, program brief, and site. Clients often come with expectations, but I wholeheartedly agree that our role is not merely to meet those expectations but to exceed them.

Berk: Do you aim to incorporate the surrounding context and influences when designing your projects?

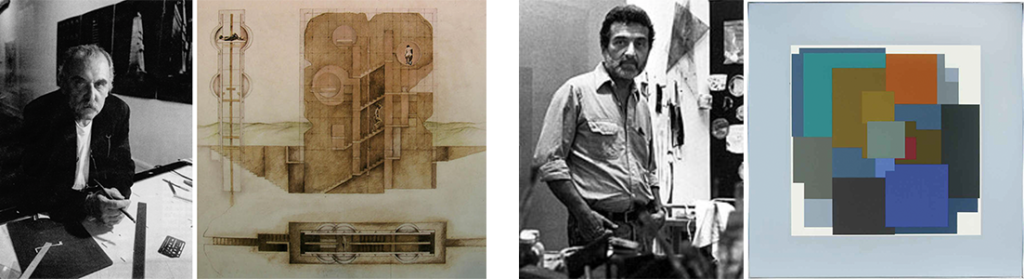

Henri: I was trained to believe that the site itself is a significant factor in inspiring architecture. Function is also a critical component, but it should never follow form. The big idea for me has always been inventing the program, infusing it with poetics. This concept really solidified during my time with Raimund Abraham (Image 2, above) at Cooper Union. He believed that the horizon, where the sky meets the earth, was the starting point for architecture.

My Swiss training initiated this perspective, but Cooper Union added an intellectual dimension to it – an ontological understanding. We constantly ask ourselves, “Where does architecture begin?” Kahn thought it started in Rome, Mies in the medieval ages, and Le Corbusier in Greece. I believe it begins with the earth because we’re intervening in it – we shape, scrape, and alter the landscape. However, as Mario Botta suggests, the promise lies in the building’s existence, where the site can say, “Thank you, architecture. I am better now.” It’s akin to saying, “I am better because I’m married to my wife.” Marriage enhances us, and I believe architecture should do the same for the site.

Berk: The site and the proposed project should work together, complementing each other.

Henri: Yes, indeed. They should complement each other. However, it’s worth considering whether one should dominate the other, depending on the project. In my view, as a Swiss, I seek a neutral balance, a complicity between the site and the design. Switzerland is known for its neutrality, but it is an armed neutrality – which redefines what neutrality means. That tension can be quite interesting. I might have learned this from Raimund because of another teacher that I had in Lausanne, Robert Slutzky.

Bob was always gentle in his teaching and introduced me to several formal cubist questions. I also noticed that European architects often drew inspiration from painting, while American architects tended not to. There’s a pictorial dimension that influenced European architects, and I inherited that way of thinking. However, with Raimund at Cooper Union and later John Hejduk, both at Cooper, I discovered a different way of thinking, a quest to unearth the roots of architecture. It felt like there was something more, an added value that Cooper Union provided.

Berk: You had a fascinating story about one of Michelangelo’s statues. Could you share it again?

Henri: Certainly, when I arrived at Cooper Union, I was enrolled in fifth year, and one of three international students. I decided to study under John Hejduk because of a partner in a Lausanne office in which I worked in Switzerland had studied under John. However, when John (this link is about my encounter with Bacchus, the God of wine) introduced the thesis course, it was a bit overwhelming for me, to say the least. I thought I knew what architecture was, but I felt I couldn’t handle the profundity of this thinking.

So, I turned to Raimund Abraham who was teaching fourth year, hoping for a different perspective, but he had a similar approach, and he became my second inspiration. His take on the site, made me reflect on places of worship like mosques, synagogues, and cathedrals. How did people carve in inert materials the belief in a God they’d never seen and would never see? I learned that for me, this is the power of architecture. Perhaps a bathroom doesn’t warrant that same power, but from that moment on, I understood that this is what architecture means to me.

The struggle then becomes how to realize that vision amidst financial constraints and spatial challenges. There’s always the distinction between “high architecture” with a capital ‘A’ and “architecture” with a small ‘a,’ which doesn’t mean the newer designs of Chipotle, McDonald, or Panda Express; it still represents substantial architecture. That revelation blew me away, to use an American term. I suddenly thought, “How did they carve inert materials to make you feel like you’re breathing with the divine?” It was a revelation, crazy as it sounds.

Berk: Do you believe there’s such a thing as a “good” architect, or does it depend on the project? For instance, when we look at someone like Le Corbusier, was he a great architect, or did he simply have the fortune of working on great projects? Can we trust a person’s ideas to be consistently great, or does it ultimately come down to the projects they create, defining who they are as architects?

Henri: That’s a complex question. Le Corbusier is undeniably a great architect. Personally, I find some of his urban interventions rather unrealistic, almost in a negative sense. However, what I appreciate about Le Corbusier is that, as students, we were immersed in his work. I loved his forms and concepts at that time. However, as I’ve grown older, perhaps over the past 20 or 30 years, I’ve developed a different perspective.

I’m not as enamored with his forms anymore. I can’t say I dislike Villa Savoy, but it doesn’t evoke, for me, the sense of domesticity and elegance it might have in my youth. It’s become more like one manifesto after another. In short, my colleagues might consider architecture as the highest authority, where you belong to a lineage that includes Alberti, Brunelleschi, Le Corbusier, and others.

I agree with that perspective, but I see myself as an architect of everyday life. I prefer to remain somewhat anonymous and serve people. It doesn’t mean I won’t strive for excellence and create great architecture, but I doubt I would ever be a “corporate” architect. Even if I had the talent, I don’t think I would fit that mold. To be an extraordinary architect, I believe, and pardon me for saying this, you must be somewhat of an “asshole.” I find that approach inappropriate.

Especially in academia, some schools may train you to adopt that attitude. However, I believe there are pressing issues like sustainability and real crises (a Call To Order) we need to address. Just look at everything happening around us. It’s not enough to say, “I find this beautiful emotionally.” Yes, aesthetics matter, but what is the urgency? There’s certainly genius in this field, but I also believe that the best idea doesn’t always come from the most famous names.

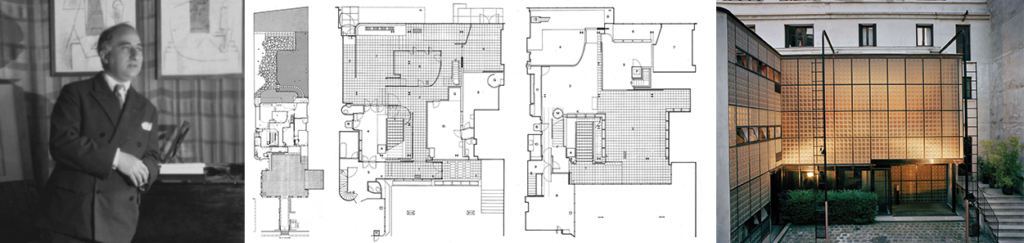

Pierre Chareau, a French architect, designed La Maison de Verre, the glass house in Paris on Rue Saint-Guillaume, and it’s an architectural epiphany. His work is part of the same lineage and timeframe as Le Corbusier, yet it feels so much more domestic. When Chareau came to America and designed the house for Robert Motherwell, it wasn’t as successful. He only did two or three more buildings, but that one structure, that building, is always celebrated in architectural history and theory books.

Then there’s Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Louis Kahn to mention a few of my generation, who truly became a master only around the age of 50, after maturing. Everyone has their own unique architectural autobiography. I believe Le Corbusier came onto the scene at a very opportune time. He was politically astute and made strategic choices. During the two world wars, when work was scarce, he developed intellectual concepts that took the form of manifestos. I think that they significantly contributed to his success.

On the other hand, Frank Lloyd Wright just kept creating, going bankrupt, having multiple marriages, but never failing to surprise through his architectural vision. But everyone has their own journey. The notion of learning or practicing like a Howard Roark seems a bit outdated to me now, personally -in fact very outdated given the today’s needs for architecture.

Berk: Would you say that young, famous architects’ early projects are often innovative and extraordinary, but as they gain fame, they tend to design for the sake of impressing rather than serving? Are they more inclined to build sculptures rather than habitable buildings?

Henri: That’s true to a certain extent. A friend of mine, Scott O’Daniel, worked for several years for Frank Gehry in Santa Monica and now practices in New York with RAMSA. He mentioned that Frank Gehry’s clients seem to no longer want to hire him because of his age; they want his artistic touch. Even Mario Botta, I believe, as fame grows, architects may find themselves constrained. Are they still able to innovate as architects, or are they merely responding to clients’ expectations for a particular style? Take Richard Meier, for example; he’s an extraordinary architect, but many of his designs look remarkably similar. I wonder if he ever thought, “Can I please try something different?” That’s why I admire Rafael Moneo.

Rafael was the Dean at the GSD Harvard, a Pritzker Prize laureate, and a fabulous architect. Some students and architects don’t like him because each of his projects is different. Some I adore, some I haven’t seen, and some leave me ambivalent, but I find his architecture extraordinary because it always responds to something unique. In contrast, Richard Meier’s work has become easily recognizable, whether in Barcelona, Tel Aviv, or elsewhere, you can spot a Richard Meier project.

Personally, I believe this attitude is the potential “death” of architecture, at least in my perspective, even though I haven’t achieved anything close to their caliber. It becomes a mere stamp of authority; a signature building – Richard Meier, Mario Botta, Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, you name them. They have the fame, and I think that when you reach that level, you have to confront the question of whether you are a true master or simply a star architect. I believe they are more akin to star architects.

A star architect is also an author, a critic, a historian, a social commentator – and eventually, they may stop creating actual architecture because it becomes increasingly challenging. Ultimately, architecture has become a business. You can’t always say, “It doesn’t matter; just don’t pay me if I can do what I want.” You have a family, you have an office to run, and that’s when you must ask yourself about the distinction between politics and diplomacy. Diplomacy involves coming together, negotiating, and each party walking away with something essential. Politics, on the other hand, often involves winning at the expense of someone else, and I find that less interesting.

Berk: What are spatial qualities you are interested in?

Henri: They have changed over time, and now I think that I am at peace to say that I am a postmodern architect -in a certain way. I love so many different things, but perhaps most importantly, the question, the architecture question of silence over discourse is at the center of my preoccupations. When you came to our home, you saw various interests reflected in the design of our home and how we inhabit it. I would say that what I do not like is an architecture that tends to be overly formal for the purpose of simply making a statement. I find it somewhat childish, like something you’d see in a second-year or first-year project. It doesn’t seem deserving of construction. While some projects may be superb, they don’t particularly impress me.

At this stage of my life, I believe that architecture should offer spatial elements that surprise in terms of the sequencing of spaces, the sense of discovery, and the unexpected transitions between them. Space should lead you in one direction and suddenly change or slightly inflect, providing something different. However, I’m starting to realize… I once wrote a blog post about the enfilade (Image 7, above); you can take a look at it.

The enfilade features a series of rooms after rooms connected by a corridor. And at the time, I detested this way of space making, simply because I felt it represented classical architecture. But now, I see the potential for change in that approach and how to reinvent this spatial sequence. When I visit grand palaces and grand staircases (i.e., recently in Latvia), I realized that it’s not something I would pursue stylistically. Nevertheless, I always attempt to understand what defines architecture.

As a designer, I seek poetry in architecture, not just something that goes around in circles and requires me to persuade you to believe in it. In terms of spatial qualities, I wouldn’t say I have a preference for high or low ceilings for example. I believe all these elements should contribute to the sequencing of space, thus should grow naturally out of the project. Perhaps I’m more traditional in the sense that if I were designing a house, I’d have a clear concept of what constitutes for example an entrance. Case in point, Japanese architecture, for instance, is fascinating. The entrance sequence there revolves around the act of removing your shoes, a practice unfamiliar in the Western context. It opens up new possibilities.

In terms of spatial principles, I appreciate the idea that there should be different ways to navigate through a space. If you remember our house, there were multiple paths – through the living room, the dining room, the library, and so on. This makes the house breathe. I also find it crucial to be able to visually measure spaces to get a sense of the place. Is it well-sighted; but I wouldn’t say that I adhere to a specific set of spatial principles or a fixed vocabulary. I might have them (especially that I always draw plans with a sectional emphasis), but I believe in the inventive sequencing of spaces, how one space leads to the next is critical.

For instance, I’m currently working on a series of prototypical houses (for me and potential clients), in which one of them features the kitchen that is situated below the bedroom. However, while the bedroom lacks privacy in the typical sense, it’s the library that creates a private buffer zone between dining room to bedroom. At the base of the library is the dining room and establishing a relationship between the kitchen and dining room. This sequence of spaces challenges the conventional notion of day and night areas.

In these projects, and in fact in any of my projects, I seek to find new ways of interpreting function, not merely to claim that I’ve done something no one else has. It’s about reimagining how people live and challenging the conventions of form, spatial qualities, geometries, and spatial adjacencies – all with a purpose, not just for the sake of reinvention. For example, when an elevated floor meets a window, it can become a seat with a desk. This all makes me realize the potential for rethinking the use of space. Why do we always have vertical storage? Why not create them horizontally for example like in Hong Kong’s micro apartments? Constraints drive my creativity. If there are no constraints, I’ve learned to create them.

Berk: We only use the bed during the night, when it is time to sleep, yet it is always there, taking up so much room. I believe there are opportunities to explore with that. You mentioned in an earlier conversation that you were inspired by the airplane tables that fold back into the armrest. Can you talk about how some things we look over in our everyday lives could inspire great architecture?

Henri: Well, that’s the thing; I believe in looking at everything as a pretext for inventing new spatial qualities. For example, I contemplate how to make life comfortable on long flights, like my recent 17-hour economy-plus journey to Singapore. I was thinking how can minimalist spaces, such as airplane bathrooms or my seat, be functional for extended periods? These aspects intrigues me, while for other they may seem mundane questions. Then there are things like the bed. I appreciate having a bedroom, but I often wonder, what if I didn’t have one?

Our home is quite luxurious spatially; you probably have a similar situation in Turkey. But how do we design spaces not just for people like us but also for those who can’t afford an empty living room , a bedroom for 18 hours a day? I find that intriguing. We have a 6,000-square-foot house, but if I lived in an apartment, I’d question equally requestion how rooms can serve multiple functions.

Perhaps this relates to ideas of the 21st century, the hybridization of spaces, not just functions distributions. For example, in Asia, there’s a blending of different functions that we haven’t fully explored in the Americas. I also think about repurposing spaces during crises, like Cowgill Hall serving as a potential hospital during the COVID pandemic. It could have had hundreds of beds where are studios are currently located, and if the need required surgery rooms, they could be located in rooms 300 and 400 for example. This idea of adaptability is crucial for the 21st century.

Berk: That, in itself, could be a thesis.

Henri: Absolutely. Responding to specific functions by interpreting the program will be one of your responsibilities as an architect. However, in a decade, the entire building might need a new purpose. For me, sustainability is key. I prefer living in older buildings because rooms can, and have, transformed over time. My current room at home may have been a bedroom fifty years ago, but now it’s an office. Tomorrow it could be a library or a kitchen. Older buildings were less function-specific; they had ceremonial spaces and can easily adapt to our contemporary model of living. Post-functionalist ideas still focus heavily on functionality.

I was educated in that paradigm, but I realize that it has its limitations. I’m always considering how I want to teach students (how students can learn) to think differently. My challenge is instilling fundamentals while nurturing the desire and appetite to think outside of the box. We may not know where that leads, but being ready for it is a gift a faculty member can offer to their students, in my opinion.

Berk: You know how dense cities are becoming and how much land we are using, we are always building, trying to be better and bigger. Why don’t we take a step back and try to refine what’s already built? We have so many buildings sitting, rotting, and waiting.

Henri: That’s the question. We were educated in Europe with ideas of renovation, restoration, rehabilitation, adaptive reuse. Those themes made architecture great. Take Carlo Scarpa, for example (Image 9, above); he dedicated his entire career to such endeavors. These ideas were not as prominent in America initially, but they’re gaining traction in big cities now. For example, money, sustainability, and the impact of COVID have pushed people to rethink their use of office spaces.

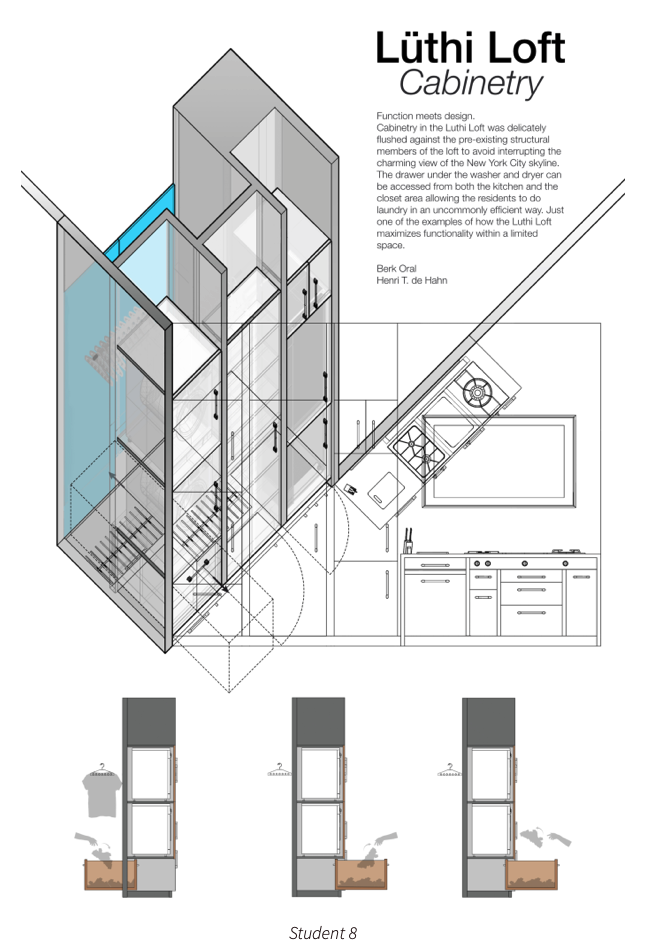

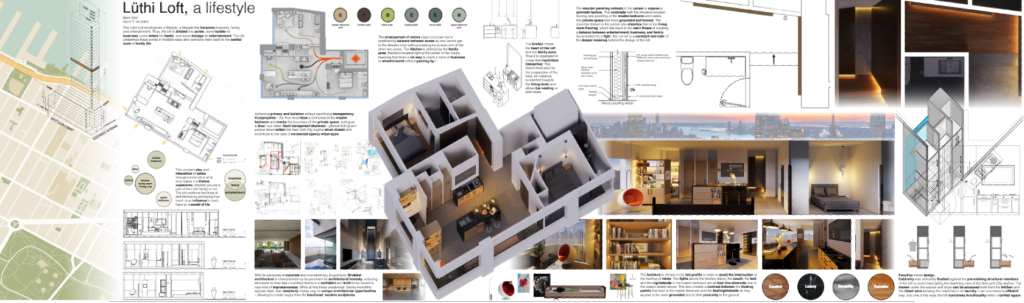

Many are now converting them into apartments because skyscrapers weren’t initially structured for residential use, and they’ve found ways to make it work. Building structures that become obsolete in just a few years is no longer sustainable; we can’t afford that. That’s why preservation matters. My argument is, why don’t we emphasize these aspects more in our education? If you hadn’t undertaken this renovation project with me during your second year [see project below, Image 10 and 12], you might never have delved into the world of detailing, furniture design, choosing art, and adaptive reuse. It’s unfortunate that these aspects are often overlooked in academia when it comes to issues of preservation.

Berk: Unfortunately, these subjects are often underemphasized in education.

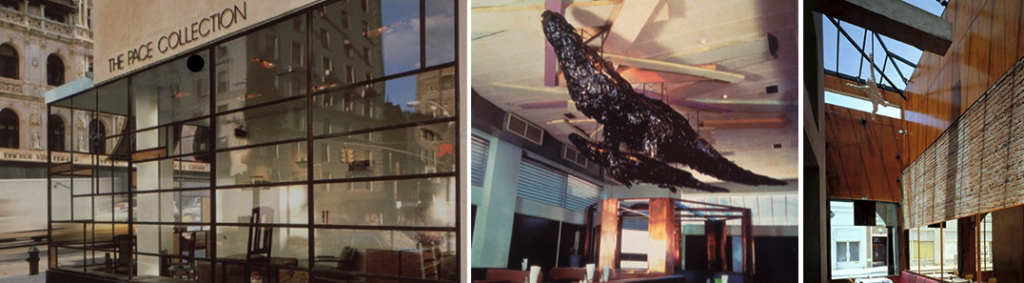

Henri: And that’s precisely why we’re at risk of becoming obsolete as a profession. Because these are the kinds of projects you’ll be working on. Interestingly, many renowned architects like Steven Holl, Frank Gehry, Morphosis, (Thom Mayne and Michael Rotondi) started their careers with small renovation projects (Image 10, above). Their work is commendable. It doesn’t mean you have to build something new to consider yourself a successful architect. It comes back to the fundamental question: What do you believe is your role as an architect?

Is it about speculation, provocation, and conceptualization? Is it solely about serving wealthy clients? Or is it about adding value to someone’s life? You’ll discover your own path as an architect, and there’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Take, for instance, the room you’re in while studying in Boston; given what I see on zoom. It’s essentially one large rectangle with a kitchen, a table, and a visual separation allowing you to see the bedroom through the ceiling. It’s just one room, but it’s now an apartment. I find that quite remarkable in the spatial distribution in such a small urban space.

Berk: Do you think there is beauty in achieving more with less and discovering how efficient small spaces can be?

Henri: I believe you’re touching upon the relevance of developing new strategies for spatial organization when dealing with limited space, and I’d say absolutely. America is a vast continent, but I recently spent a few days in Istanbul and Switzerland, where space is limited, and vertical expansion is the norm. However, there’s a challenge when you have regulations and other constraints. Densification is a necessity. I also believe it’s a matter of mindset. In Europe, there’s an understanding of living collectively and close to one another, which is different from the American ideal of having a spacious house with a useless front yard and back ground as a private playground.

To practice in such contexts (I,e. being more efficient spatially), there needs to be a shift in mentality because without it, nobody will invest in your speculative dreams. You’ll have to decide how to proceed, similar to Le Corbusier, who had speculative ideas but eventually turned them into concept and a tangible reality. He had clients, often affluent ones, and he participated in numerous competitions. After the war, there was a demand for social housing that aligned with his vision, like the Unité d’habitation in Marseille, Briey-en-Forêt, or Berlin. It’s about investing time and energy. The concept of an economy of means should not merely be a passing style; it runs deeper, almost ontological. It can be executed well or poorly.

Would you prefer two or three rooms over one single room? Absolutely. But the question is whether you can afford it or if you choose to be efficient. Interestingly, many affluent individuals are conservative yet sustainable. Sometimes those with fewer means might be less sustainable, not because they want to be, but due to a lack of awareness about recycling and other practices. There’s a cultural dimension to sustainability. That brings us back to the issue I mentioned earlier: how and when should universities train future clients, like yourself, while also educating non-design students who are now very conscious of environmental challenges? It’s a complex question. You will always have big ideas, but you need to decide what’s worth fighting for.

Berk: I guess that is more of a personal question. The answer could change based on one’s beliefs.

Henri: In hindsight, if I hadn’t come to America to study, I believe I might have formed a partnership with a friend and become an interior-architect. But I ended up taking a different path that allowed me to do other things. My life, in a way, feels like a fluke. Becoming a faculty member was never in my dreams, let alone becoming an administrator. I never imagined myself in such roles. But over time, I realized that these positions offered me opportunities to travel, teach, and influence the lives of many students and let faculty grow to their full potentials – perhaps around 10,000 students by the end of my career. Instead of having designed three extraordinary buildings that might be part of architectural history and theory, I guess that I chose for me a more challenging, yet humbler path.

Some second-year students may perceive me as at the beginning as harsh, but I don’t believe I am. I like to challenge them. I don’t want to imply that I’m different or more sophisticated than other colleagues, but I simply don’t derive pleasure from stepping on others to achieve success. That aspect of architecture-as well as in teaching were one may request that a student replicates the faculty’s philosophy-where talent often is coupled with cunning, doesn’t appeal to me. It could be my preconception, but I’ve been fortunate to work with wonderful clients without needing to be ruthless to secure projects.

Berk: What’s the most important part of the design process?

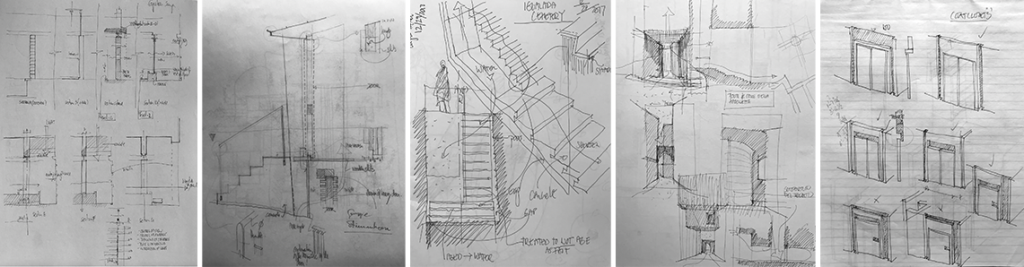

Henri: I believe that the most crucial part of the design process is intuition, combined with a consistent and open approach. When I design, I continuously sketch and try to understand that the project will never be precisely what I initially drew. There’s an element of correction and calibration to align with my true vision, but I also appreciate the accidents that occur during the process. These accidents can lead to innovative ideas and take the project in unexpected directions. The best design projects, in my opinion, are the ones where the project starts telling me what it wants to be. It’s about feeling confident in your process, allowing intuition to guide you, and letting the design evolve organically.

Typically, the design process involves having a function, site, client, budget, and idea, and then proceeding with the project. But what I find interesting is when the design itself starts to assert its character and direction. It’s about finding a model for life within the design. I embrace the errors and allow the project to guide me towards its ultimate form. This approach extends from the initial concept to detailing and construction, maintaining an attitude of investigation, control, and non-control.

In architectural education, there’s often an emphasis on construction in European schools. When students complete their studies, they are registered architects, and they understand many important practical aspects of the art of building. In contrast, in American schools, there’s sometimes more focus on the idea of the architect as a genius with incredible design skills, with, to my desolation, carries less emphasis on the practical aspects of architecture. This can lead to projects that are more about individual creativity rather than thoughtful, functional design interpretations. It’s an important distinction to consider in architectural education and practice.

Berk: What interior and exterior spaces do you think architects should pay more attention to, or often overlooked, but could have great potential to turn into something much greater.

Henri: In terms of architectural attention, I believe that interior spaces are often overlooked or under defined for architects. People tend to think of space in a general sense, but there’s a significant potential for architectural innovation when it comes to interiors. For example, when considering renovations or adaptive reuse projects, understanding the different layers of sophistication within interiors is crucial. This includes how interior spaces blend with the architecture, cabinet design, furniture selection, and even details like metalsmithing. By paying more attention to the interiors, architects can create truly unique and functional spaces that enhance the overall design.

Berk: Picking out the furniture, color palette, artwork, decorations etc.

Henri: Yes, I find it exciting, but I suspect that many architecture students who haven’t had the opportunity to explore interiors in depth might initially question its importance. However, for those who have experienced it, they often discover a sense of delight in choosing furniture and crafting interior spaces. I believe there’s a significant difference between designing the overall architectural space and designing interiors. Unfortunately, in America, the level of detailing in architecture can be lacking. While students may learn how to construct well, they may not receive adequate education in the fine art of detailing, which is a critical aspect of architecture.

When it comes to exterior spaces, I think it’s an area that is often overlooked or not given enough attention in architectural education. Many architects tend to focus primarily on the building itself as an object, and forget about the context and surroundings. However, this is changing, especially with a growing emphasis on sustainability and considerations like landscaping. The level of attention to exteriors can vary based on the architectural program and region. Some programs are more focused on cultivating a deep understanding of architectural dimensions beyond just the building itself, while others may prioritize different aspects of design, like formal modernism. It ultimately depends on the architect’s education and philosophy.

Berk: I believe that as an architect, when you’re designing a space, you can’t just draw an interior wall and say that’s where the kitchen is going to go. If this is your building on the outside, I think you should claim it on the inside as well and go into the deepest detail as selecting the wall color, the furniture, and even making furniture. I think there is another beauty in that. It’s not like a hobby. It’s, I think, essential to the space you create to serve its utmost capability and potential.

Henri: Absolutely. Most architects would agree with this sentiment. However, the question often arises: when designing furniture, do you approach it as a cabinetmaker, an interior designer, an interior architect, or an architect? I’ve raised this issue before because I think it’s crucial to consider why architecture thinks that it must single-handedly solve all the challenges related to a building and its site. Can’t we involve different disciplines for specialized input? I’ve noticed an underlying animosity between architects and interior designers, which I believe stems from stereotypes. Interior designers are often seen as decorators, primarily focusing on aesthetics, while architects are perceived as the experts who can handle everything. This arrogance among architects continues to prevail, assuming we can do it all, even furniture design.

For instance, I recently had some students visit, and they tried out the two original 1936 Aalto chairs I own. They pointed out that, although visually appealing, they were not comfortable. I haven’t ventured into chair design myself, partly because I recognize that many chairs designed by architects aren’t comfortable. I’m not criticizing their efforts, but I think it raises a broader question: why do architects insist on doing everything, and do they possess the requisite skills, elegance, and humility to excel in every aspect of design?

This is where my passion for renovation comes into play. It encourages a holistic approach, preparing students to understand the intricacies, diversities, and complexities of design. It’s my hope that when you complete your studies, you’ll appreciate the multifaceted nature of architectural work. I must emphasize that over the years some thesis students tend to focus solely on creating forms, producing visually appealing but impractical spaces that, in the end, lack physical comfort and functionality.

Berk: What does a façade mean to you?

Henri: I have to admit that I’m not particularly fond of designing facades, perhaps because I don’t feel especially skilled at it. However, I believe facades can convey different messages. Le Corbusier, for instance, viewed the facade as an expression of the interior. On the other hand, I appreciate Louis Kahn’s perspective, where he described the facade as the edge of the outside. This idea made me rethink facades in a new light.

There are facades I genuinely admire. Take, for instance, Fumihiko Maki‘s Spiral building in Tokyo; its facade is truly magnificent and highly volumetric (Image 14, above). I have a preference for facades that don’t reveal everything about the building. These façade-types incorporate various elements like volumes, flat surfaces, and corner details, creating a dramatic and mysterious quality.

However, it’s important to acknowledge that designing facades is a time-consuming process, often left as the last step in the design process. Ironically, it’s the first thing people see when they encounter a building. Nowadays, facades have become more technologically advanced, with considerations for factors like lighting, climate, and maintenance. They are primarily focused on sustainability and functionality rather than aesthetics.

Berk: I have a theory that when you invest a significant amount of time and energy into designing a stunning facade, it can create high expectations for the building’s interior. These expectations might be so elevated that the interior space cannot quite live up to what the facade promises. Do you think achieving a good balance between the exterior and interior is important in architectural design?

Henri: I agree with your theory to some extent. The challenge is how to design a facade that goes beyond mere formal aesthetics. For example, you have to consider elements like window placement, size, and their relationship to the interior.

Let’s take the Venetian facades as an example. They serve as representations of what’s happening inside, but they also take into account the available light given the nature of Venice’s city on waters. Symmetry is a critical factor, although it’s often asymmetrical on the horizontal plane due to the presence of water, which naturally balances the composition. If you were to create a completely symmetrical horizontal facade in such a context, it might appear overly heavy.

A facade is not just a pretty face; it conveys messages about what’s both inside and outside the building. Windows, for instance, serve various functions. They allow you to look outside, bring light into the interior, provide spaces to sit in, and even showcase different areas of the interior, like a grand living room or an attic. There are functional aspects embedded within the facade’s design, and it’s crucial to balance aesthetics with these functional considerations.

In essence, a facade is not just a superficial layer; it’s the skin of the building that communicates the architect’s intentions and reveals and conceals elements of the interior. Achieving this balance is a sophisticated process, but it’s often one of the last steps in a project, which can be unfortunate given its importance in shaping our initial perception of a building.

Berk: I know that you’re passionate about cooking. Would you say there are similarities between cooking and architecture or being a good chef and a good architect? The spices or the ingredients or the consistency of the meal are some interesting things that you could maybe relate back to architecture.

Henri: Absolutely, there are indeed intriguing parallels between cooking and architecture. I approach cooking in a very intuitive way, much like how I approach architecture. My wife, Tracee, enjoys baking, which requires following precise rules, but I prefer to innovate when I cook. Sometimes it results in a culinary disaster, but more often than not, it yields a delightful meal.

Recently, I came across a Netflix series called Seven Days Out. One of the episodes was about a Swiss chef (Daniel Hume), and he articulated four essential aspects that apply to both cooking and architecture. Firstly, does the dish taste good? Secondly, does it present well? Thirdly, is it creative? However, the fourth aspect truly resonated with me, and it’s the same for architecture: Why does this dish deserve to exist?

When I cook, it’s a moment of repose and pleasure. Sometimes it’s as simple as pasta with butter, not refined but satisfying. Other times, I experiment with ingredients, creating visually appealing and tasty dishes. This approach aligns with my architectural design process.

However, when I work with clients or even for myself, there’s a sense of accountability. I can’t design a space just for contemplation or as an afterthought. I dislike when students describe spaces as solely for contemplation without much thought. Just like in cooking, I aim to create spaces that are functional (in terms of the value of use), pleasing, meaningful, and that allow inhabitants and visitors to project themselves into the design.

So, the question becomes, why does this dish deserve to exist? Why does my architecture deserve to exist, or why does a students’ design deserve to exist, especially at the thesis level? I believe that it’s about offering a new perspective, a fresh way of thinking, and sometimes, providing more with less. If I succeed, I’m happy, and the most important thing is that the client is happy, not just because I fulfilled their requests, but because they realize that my design has enriched their lives, interpreted their daily rituals. Food is similar in this regard—it’s about pleasure, sharing, and meaningful experiences. Good architecture, like a good meal, should consistently deliver quality, whether the program is extravagant or modest, and it should always deserve to exist.

Berk: I agree. You can have the best presentation but if the food tastes insufficient then it is not a good meal, or if it tastes great but lacks presentation it will also be disappointing. Similar to external vs internal qualities in architecture.

Henri: Balance is key. It’s like having a beautifully presented dish that tastes amazing but when processed with a blender, so it looks unimpressive. It’s about finding that balance, and I must admit, I may not have perfected it, but my intuition guides me in creating visually appealing and flavorful dishes, combining flavors, colors, and organization. In architecture, it’s the extra value you bring, the excellence you deliver to the commission, that sets you apart.

Berk: Lastly, I know that you’re passionate about traveling. What city or country do you think sets a good example for architecture?

Henri: Hands down, I have a fondness for Asian cities. They embody progress while maintaining a reverence for their colonial history. Singapore, for instance, impresses me. Despite its limited resources, it has achieved remarkable development since 1965. They’ve made strides in sustainability, with innovations like recycling 90% of ALL their water sources. Hong Kong is another city I appreciate (love) due to its fascinating contradictions. It combines high-end luxury shopping malls with century-old tea stores, offering a glimpse into the city’s diverse heritage. Older cities like Delhi and Istanbul intrigue me with their rich history and cultural significance.

Meanwhile, cities like Paris, Rome, and Vienna captivate me with their layers of history and sophistication. Each city has its distinct periods. Paris, for example, is known for its 19th-century charm. We don’t really think about Paris during the Medieval times because it was terrible. Recently, my wife and I and I have been discovering lesser-known cities, like Riga in Latvia; a sweet, beautiful city, where my father used to live for some time. I also have a sentimental attachment to Lausanne, where I studied. These cities are more about emotions and memories. I often leave a part of myself in a city, a memory that I retrieve when I return. I build my own cities in a way, collecting memories over time.

Every city has its own appeal, and Tokyo, though I’ve only visited once, fascinated me. Hong Kong, with its elegance, sophistications, contradictions, and Asian Swissness, remains a favorite. It’s life is so vibrant, and everyone is so polite and it consists of so many parts worth discovering and exploring. New York, where I lived in the ’80s, was full of tension and excitement, but it’s evolved to become boring to me over the years. Los Angeles is an interesting place to visit, but I don’t find it particularly beautiful. San Francisco boasts an appealing aesthetic, but the cost of living can be prohibitive. Each city has its own unique character and charm that is inspiring in its own right.

It has been a delight to be interviewed and asked to spontaneously respond to questions that were not easy, but that came from an interviewer who was keen in understanding the complexity of a profession that he is soon to enter. Thank you Berk.