About miniature metal buildings. While the practice of architecture can be traced back to the first architectural treatise by Roman architect and author Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, the education of an architect is rather recent in the history of our profession. Morphing from the French Ecole Royale des Arts into the famous Parisian institution of the Ecole des Beaux Arts, this 19th century schooling became the world’s first educational system to train architects. Based on a rigorous curriculum where the professor was master, most future graduates were expected to serve their professional careers completing governmental projects under France’s President Napoleon III.

The Grand Tour

Prior to this state-sponsored model, guilds throughout Europe took a leading role in the construction of monuments and architectural structures. Organized by trade and practicing in a single city, skills were kept local, and the secrets of their crafts were passed down to novices through hands-on experience. With the advent of formalized education, the learning of architecture expanded to include in situtravel opportunities to experience art and architecture. These moments took on an important role in the 17th and 18thcenturies, and were called the Grand Tour. In fact, this way of learning continues to today and remains central to many university signature off-campus programs.

It is interesting to note, that the Grand Tour was equally favored by 19th century American financiers, such as John Jacob Astor, Henry Clay Frick, Salomon Guggenheim and J.P. Morgan who, during their numerous travels, purchased with vigor and astuteness their first works of art. These carefully curated acquisitions became the foundation of great private art collections, many of which are the basis of today’s famed American museums.

Souvenirs

Central to these cultural and educational exposures were young British aristocrats and, later upper-class students in architecture, who were mentored by tutors and traveled over the course of several months primarily to Greece and Italy to gain a cultural appreciation of ancient art and architecture. Mostly recognized through the vestiges of classical antiquity, the rediscovery in 1738 of the ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii (two famous Roman cities destroyed and preserved by the volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.), brought the ideals of the Renaissance to the forefront of public consciousness.

This led to the creation of a new style called neo-Classicism.In the context of the Grand Tour, and focusing primarily on the decorative arts and the material culture of specific sites, students carefully recorded their impressions in sketchbooks and measured drawings. Upon their return home, the need to preserve something more than their own visual memories led to the creation of mementos, commonly described as souvenirs.

Call them knick-knacks, memorabilia, kitsch, trinkets or simply low art (contemporary descriptions that we give to those disposable objects), souvenirs first and foremost catered to the taste of their aristocratic clientele, thus having a certain cachet in terms of objects. From commissioned paintings, to engravings, etchings, sculptures and ornaments, each of these worldly possessions expressed the individual’s interests, and in the lineage of patronage, their ambitions to collect particular art-objects.Reflecting on these mementos,

I was reminded that the word souvenir derives from the Latin subvenire, to come into mind, and its derivative in French, meaning “a remembrance or memory,” thus the idea of an individual memory of a place, an occasion or person transformed into a souvenir.

I collect miniature metal buildings (often called souvenir buildings or miniature monuments) and have accumulated approximately 400 pieces (Revised 09.02.2023) over the past three decades. They are part of those objects produced in the later quarter of the 19th century for the Grand Tour as a result of the rise of popular tourism. Ever since I inherited one from my parents, I have been fascinated with the idea of collecting them. The ones I favor are cast from pot metal, pewter, brass, lead and copper (now unfortunately produced in resign, which does not offer the beautiful patina of the vintage metal ones, and which I avoid at all costs).

These objects represent icons of a city or place. Most often, they feature architectural landmarks such as buildings that convey the identity of a place or a symbol of a city. From pagodas of the Orient, to the statue of Liberty, from the Eiffel Tower to the World Trade Center, each miniature expresses the overall tectonic qualities of an existing building. However, souvenirs as true repositories of memory and miniatures buildings seem often at odds.

These objects represent icons of a city or place. Most often, they feature architectural landmarks such as buildings that convey the identity of a place or a symbol of a city. From pagodas of the Orient, to the statue of Liberty, from the Eiffel Tower to the World Trade Center, each miniature expresses the overall tectonic qualities of an existing building. However, souvenirs as true repositories of memory and miniatures buildings seem often at odds.

This may simply be because souvenirs (memories) are intangible feelings while souvenir buildings hold an experience that the owner rarely has encountered; to hold a building in one’s hands, touch and view it simultaneously from any angle. This haptic experience makes us as owners monumental at the expense of the building.

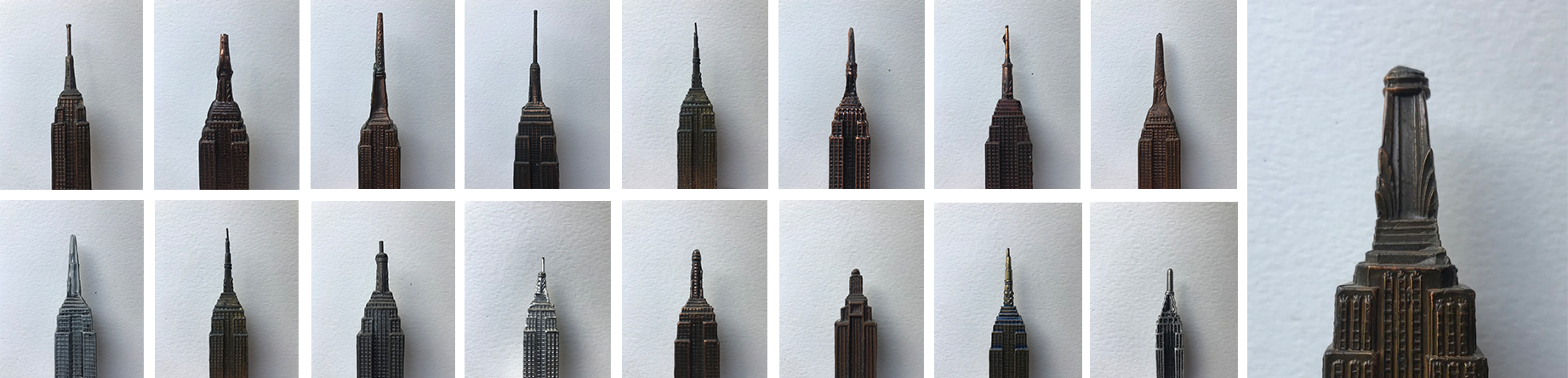

Over the past century, miniature buildings were produced in multiples and at different scales, and offered a range of detailing from abstract to refined. The inequality of rendering, especially when certain materials were used (the cheaper the material, the less detailed was the model), often enables me to know if they are vintage artifacts, thus defining the period in which they were produced.

Case in point, I have almost 29 (revised 09.02.2023) different Empire State buildings, from small to large, poor to wonderfully detailed (the molding is also key here) and 21 Status of Liberty (Image above). Regardless, I like all of them as they form a great unity and a history of how this iconic building was represented. But my favorite one shows the top and the spire of the building in an unmistakably Art Deco style, suggesting that its fabrication was done shortly after the completion of the building in 1931 (see above images).

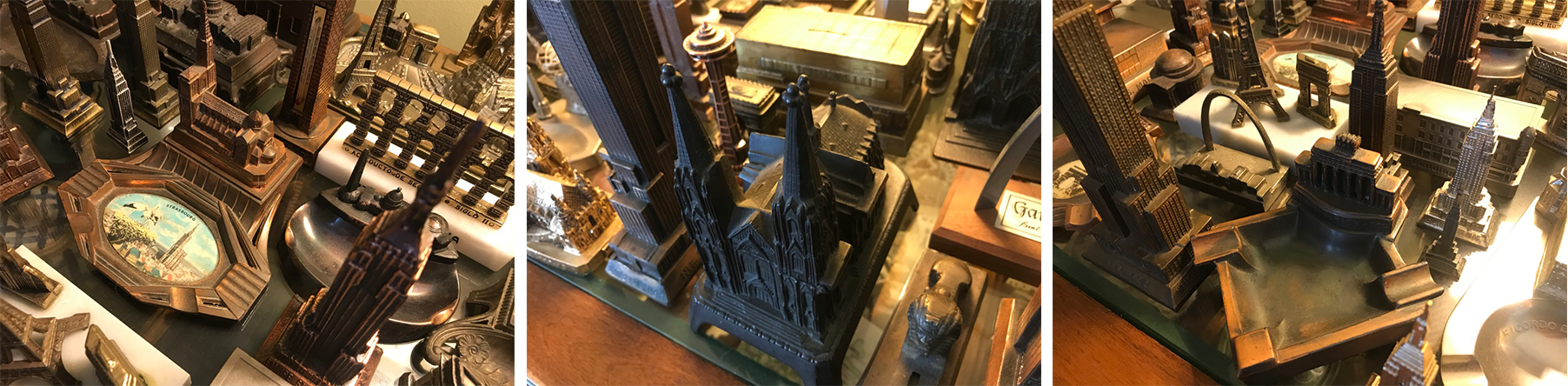

Beyond their representational purpose of replicating a three-dimensional architectural form (i.e., portraying a familiar or famous building), miniature souvenirs often provide additional features, such as serving as a thermometer, bookend, jewelry box (particularly the Grand European cathedrals with their large interior volume), or as desk pieces with calendars, inkwells, pencil sharpeners, ashtrays, and salt and pepper shakers. Some commemorate World’s Fairs (I have those of the Eiffel Tower in Paris (1889); the Trylon and Perisphere (1939) and the Unisphere (1965) in NYC; the Gateway Arch in St. Louis (1953); Space Needle in Seattle (1962), and the Sunsphere located in Knoxville (1982) to name a few).

Other buildings in my collection represent Roman monuments (aqueduct and amphitheater), or modern civic landmarks such as those found in Washington DC (Lincoln Memorial, Jefferson Memorial, US Capitol, Washington Monument, and the White House). Some are more mundane, yet remain as interesting.

For example, miniatures feature local suburban savings banks or financial institutions, serving as publicity to enroll new members while offering an artifact acting as a coin bank (HSBC banking corporation still offers this teaser if you open an account with them at their main Hong Kong branch). Those miniatures seem ordinary, and because not mass produced, they are often rare and I am proud to have found some of those gems. Their modesty and discretion complement the collection of those landmark miniatures by adding uniqueness to an imaginary city skyline.

Yet, beyond the pleasure of discovering and collecting new souvenir buildings, my greatest pleasure is to envision a new city each time I dust my collection. While dusting is a necessity to keep my allergies in line, it offers me countless ways to mingle new groups of similar buildings (i.e., Eiffel Towers in Paris -yes Tokyo also has its own “Eiffel Tower”), allowing me to compare and contrast between sizes, quality of detailing, period of production, patina and metals used for fabrication.

Yet, beyond the pleasure of discovering and collecting new souvenir buildings, my greatest pleasure is to envision a new city each time I dust my collection. While dusting is a necessity to keep my allergies in line, it offers me countless ways to mingle new groups of similar buildings (i.e., Eiffel Towers in Paris -yes Tokyo also has its own “Eiffel Tower”), allowing me to compare and contrast between sizes, quality of detailing, period of production, patina and metals used for fabrication.

The collection is enhanced by their multiplicity, thus creating neighborhoods within cities, cities within cities. At other times, I like to envision make-believe cities where landmarks are juxtaposed with other buildings from far continents (i.e., Status of Liberty in NYC with a Hong Kong Pagoda), provoking unexpected associations, analogous cities, both geographically and historically. This post-modern attitude towards the city, of setting side by side buildings that randomly create new spaces and places, offers rich and complex meanings, and never fails to surprise me and our numerous guests.

Memories of places and buildings now enter the realm of the imagination….

For additional images visit Miniature buildings