Prague: a lesson in stairs (Josef Plečnik). There has always been for me delight in discovering in-situ urban places when studying famous, or not so famous, and, even better, relatively unknown architects. I will admit that I favor anonymous architects, as many of them have created stupendous works in silence; away from the unnecessary disturbance surrounding today’s star architects.

As a student I remember being shown a plethora of famous architectural projects. Slide after slide in a darkened classroom making it quasi-impossible to assimilate the material. And this, even if the content was—at least for my faculty—fundamental to my education as a future architect. To remedy this in-class learning, it became important for me to have self-directed field trips. In a certain way, these were also necessary to confront the faculty’s perspectives with my own experiences.

While most of my site visits start as carefully planned, they often ended up being improvised. This is because I like to get lost, especially, because after an impromptu turn of a corner I might discover an unknown marvel that needs scrutiny. It may seem presumptuous, but these surprises give me a sense of being privileged, because for the span of a second I am the only one who knows about the unique jewel.

Being a flâneur

These unexpected discoveries are described by some of my friends as me having too much time on my hands. And yet this roaming, this directionless wandering—with occasional stops at a sidewalk café to observe urban life—has become integral my travel rituals. As I mentioned in a previous blog, I favor moments of repose in cafés as they are often a place where patrons act out their lives as if the space was like their own living rooms, where intimate conversations were meant to be overheard.

In literature, this mindset of discovery through wandering, is called to flâner or being a flâneur. Writers such as Edgar Allen Poe, Honoré de Balzac, Charles Baudelaire, and closer to us in the 20th century, Walter Benjamin and Guy Debord refer to this type of person as an urban observer or people-watcher—often aloof—who wanders in the city streets observing the spectacle of daily life that unfolds in front of their eyes. This is equally true in the pictorial world where, for example, French impressionists Gustave Caillebotte, depicts the urban stroller within Paris while leisurely enjoying the newly completed boulevards (Image 1).

Be it a hobby, pastime, or simply a genuine lifestyle, it is my way of discovering, and many of these impromptu moments become memorable and key to an understanding of my city.

The Prague castle

During a trip to the Czech Republic, I spent several days with students in the capital city of Prague. The day’s first stop included a visit to several of Slovenian-born architect Josef Plecnik’s interventions (spanning between 1920 and 1934 while he served as the architect of Prague Castle following the founding of Czechoslovakia as a republic in 1918). We ended up—as usual—improvising our tour of the citadel’s grounds.

For some odd reason, I omitted that day to include in the schedule the basement spaces of the Theresian Wing of the Old Royal Palace. After walking up and down Plečnik’s famous ‘Bull Staircase’ that leads to the bastion connecting the upper level of the castle with the fortification terrasses below, I noticed a poster announcing an exhibition on Plečnik’s work honoring the 150th anniversary of his birth. The exposition was in the Theresian Wing, and guess what, I was smack in front of its entrance (Image 2).

Josef Plečnik

Much is written about Plečnik’s oeuvre—describing him as a gifted architect who knew how to re-contextualize history, often marking him as a precursor of the post-modern movement in architecture. Whether borrowing, copying, or interpretating in a new way, Plečnik had the ability to quote various styles and bring them together in an unorthodox yet innovative manner.

While broad strokes are critical to underscore Plečnik’s role within the history of modern and postmodern architecture—especially when thinking of the superb urban interventions completed in his native city of Ljubljana—I believe that little attention has been given to particular key moments within Plečnik’s oeuvre. For this reason, and not surprising given my blogs on staircases, I became fascinated with the staircase in the Theresian Wing, and dedicate this blog to my findings.

Many stairs that I have written about in previous blogs, rely—as any stair should do—on the immediate environment in which it is located. Staircases are a medium to change levels, but their true design qualities have as much to do with their ceremonial purposes, formal attributes, and material qualities as they impact the space they inhabit. Conversely, the success of any stair is also the result of a careful reading of the context in which they are to be set; either existing or invented. This is what gives a stair a sense of place.

Plečnik’s staircase at the Theresian Wing

Located in the Theresian Wing of Prague castle, the staircase is stupendous in its overall simplicity. The discovery is not immediate, as one needs to proceed through a number of chicanes to reach the longitudinal tall, vaulted space where it is located (Image 4). My first impression of the staircase was great surprise. This was because it was simply there, staring at me in an understated manner.

Pushed to the left-hand wall—leaving a passageway to access the back of the first-floor gallery—the staircase was divided in two tiers with a landing in the middle. The steps were comfortable as the proportion of risers to treads were generous, inviting you to take time to ascend in a noble manner. No need to rush here, the stair and its detailing commanded the pace.

What has always fascinated me with Plečnik’s work is how he makes simple gestures grand. There are few extravagant moves that formally scream at you, begging to show off. It is in the subtlety of detailing that Plečnik’s mastery is revealed. Here, for example, the first step of the staircase—the curtail step—is inviting as it extends inches into the corridor before wrapping around the base of the staircase to form a plinth on which the remaining steps are seated.

This sense of formality gives the staircase gravitas that distinguishes it as not simply departing from the ground but being elevated, announcing its presence as ceremonial. This move is accompanied by the delicate treatment of the railing—a modular simple railing that accompanies our ascent to the second floor, counterbalancing the robust concrete materiality of the stairs. The railing only begins at the third step, allowing visual movement to underscore the notion of entrance to the staircase. The play of materials for the railing reminds me how modern furniture pairs two materials: chrome reflecting light, leather absorbing light. Here for the railing, the brass reflects light, while the teak absorbs the light.

Of note, at Prague Castle, when I looked at the protective brass connection at the end of the teak handrail, I was reminded of Carlo Scarpa’s detail at the bridge fronting the original entrance to the Fondazione Querini Stampalia in Venice. Not only is there a kindship between the two architects as they had similar approaches to restoration, but it seems evident that Scarpa was inspired by Plečnik’s sensitivity towards detailing and its tectonic expression (Image 6).

Baluster

The elegance and simplicity in both treatment of the first steps and the start of the railing, is counterbalanced by a sculptural treatment on the first baluster. A fanciful ornamental element visually articulates the right-hand side of the staircase. It is independent of the structure of the railing—anchored to the ground—and twirls around the first baluster like a lady’s bracelet. I am unsure of its significance or purpose, but knowing Plečnik’s interest in referencing material culture, it is hard to believe that this element is arbitrary or gratuitous to the understanding of the staircase.

Similar to Scarpa’s clin d’oeil to Plečnik, while looking at the almost art-deco-like treatment of the sculptural object on the baluster, I was reminded of a visit in the early 1980s to the home of Belgian architect Victor Horta in Brussels, Belgium. There, a detail on the first landing of the staircase caught my attention. The handshake-like tectonics of the handrail resolved sculpturally as an architectural transition from steps to landing. It was so unique and could not go unnoticed!

The underneath of the staircase

After admiring the first risers of Plečnik’s staircase, I moved further down the space towards the rear part of the first-floor gallery. To my surprise, looking at the underbelly of the staircase, I saw a robust, almost naked treatment of the structure. This was a revelation because the space around the staircase is narrow and does not give a holistic view upon entry (Image 4, middle right and right).

Constructed of reinforced concrete, the tapered geometry supporting the steps is similar to the folding of a piece of paper, which gives it integrity as a self-supporting structure. The only vertical element in this diagonal thrust of the staircase, is a square column—and not a piloti—that supports the landing. There is no reference here to a classical ordering system as the column’s base and capital are treated identically. There is just a hint of expression of how forces are channeled from the staircase down to the floor.

The materiality of the structure of the staircase should suggest a visual weight because of the prominence of reinforced concrete. This is especially true as it contrasts with the delicate and almost fragile expression of the railing, couple with the overall color palette of the vaulted room. But here, Plečnik does a tour de force by offering in the belly of the staircase an incredible sense lightness as it ascends to the second floor.

Railing

While delicate in both treatments, Plečnik fastens each baluster differently. The one facing the corridor is anchored to the stringer of the staircase. Because of the delicate fastening of the baluster to the railing (Image 10 middle left), Plečnik opted to treat the paring of the front and back baluster for every step with brass cylinders (Image 10 left). This tectonic expression gives robustness to the anchor and suggests plumb bobs. In fact, this connecting treatment from the railing to the steps is similar to the plumb lines that give a visual true vertical. A beautiful tension is created between the slender balusters and the concrete stair.

The inner fastening of the baluster does not touch the staircase. Fastened only to the wall at key moments, Plečnik creates a sense of levitation along the entire inside railing.

Conclusion

What fascinates me in Plečnik’s work is how simple gestures are made grand. Perhaps this is what draws me to his work although they have clear classical attribute developed in a postmodern language. I should also mention that upon my visit to the exhibition on the second floor, I encountered another stair, this one more contemporary, and made from steel. A wonder in its own right that complemented Plečnik’s overall intervention while establishing a clear formal departure in form, geometry, and materials.

If anyone knows who the designer is of that stair, please leave a name in the comment section of this blog. Thanks!

Postscript

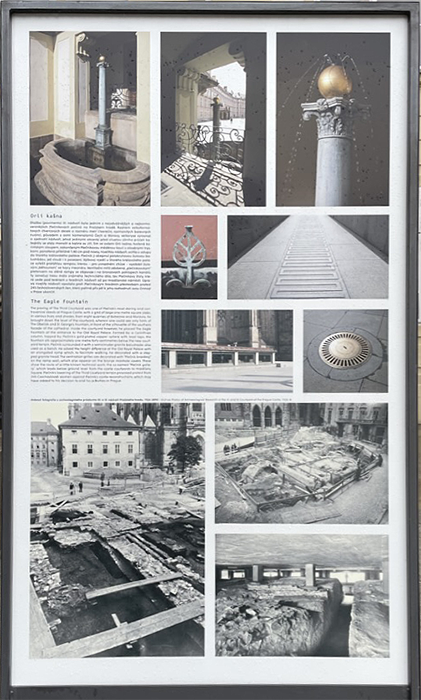

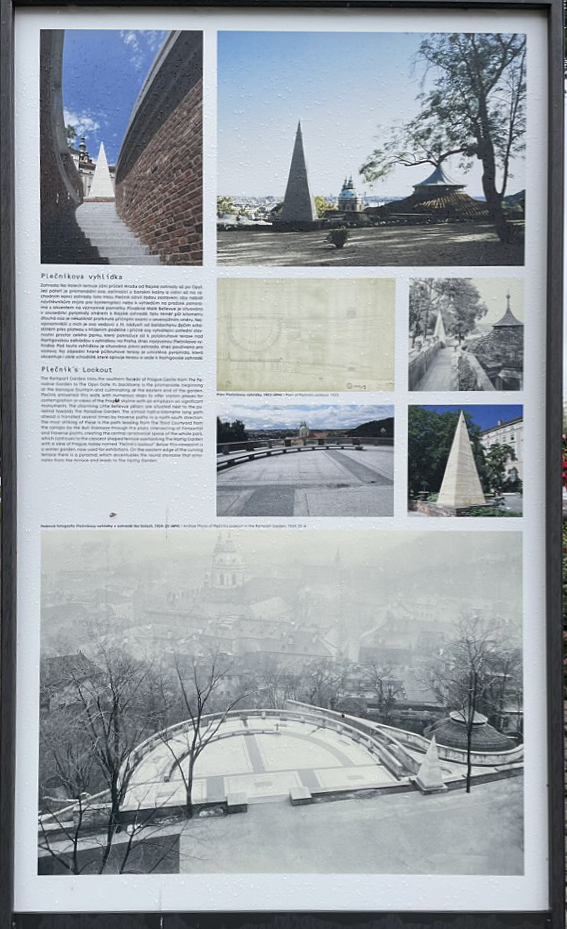

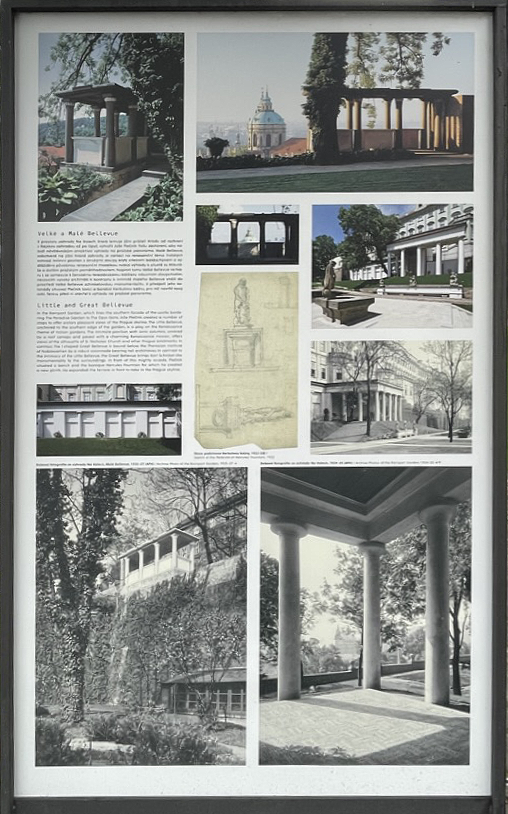

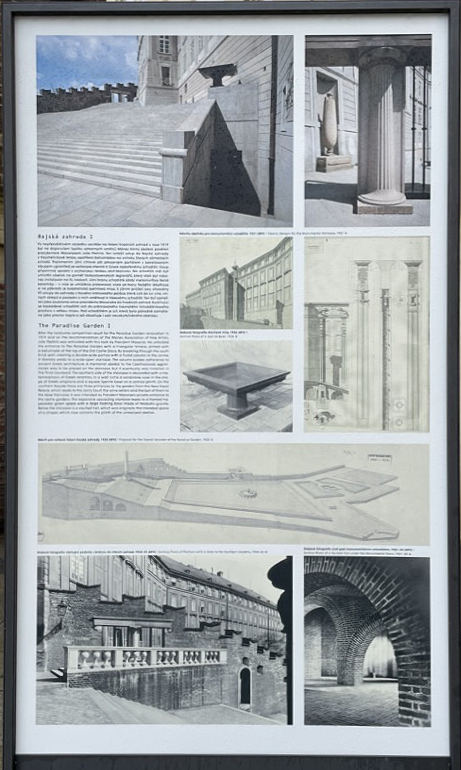

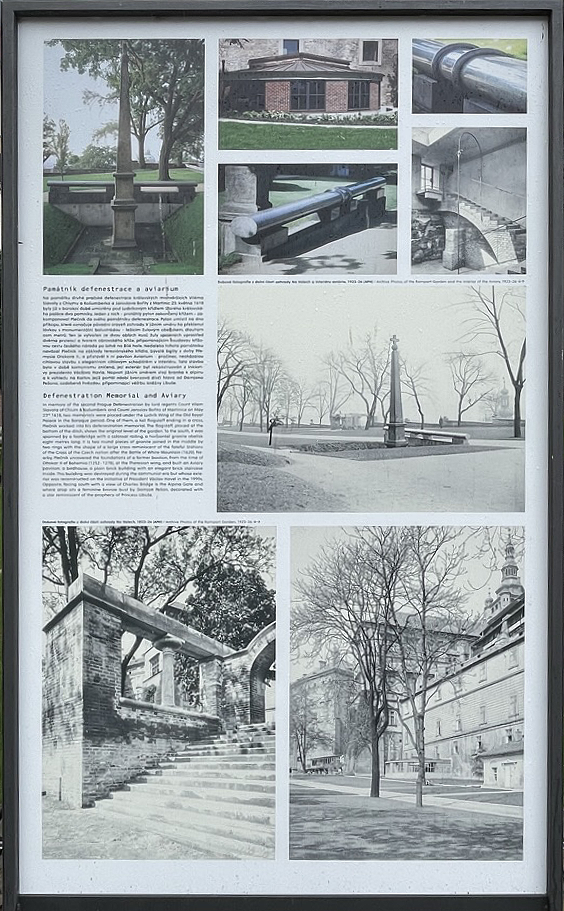

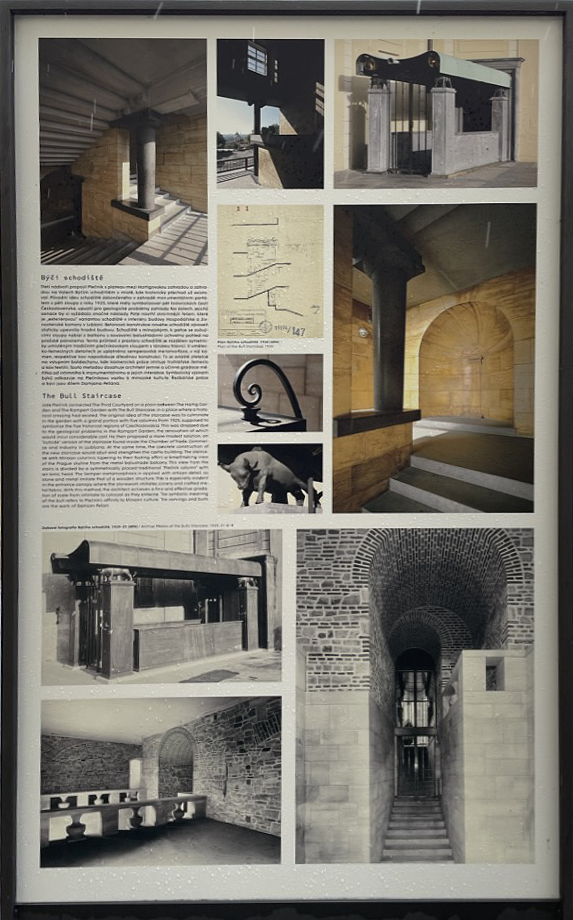

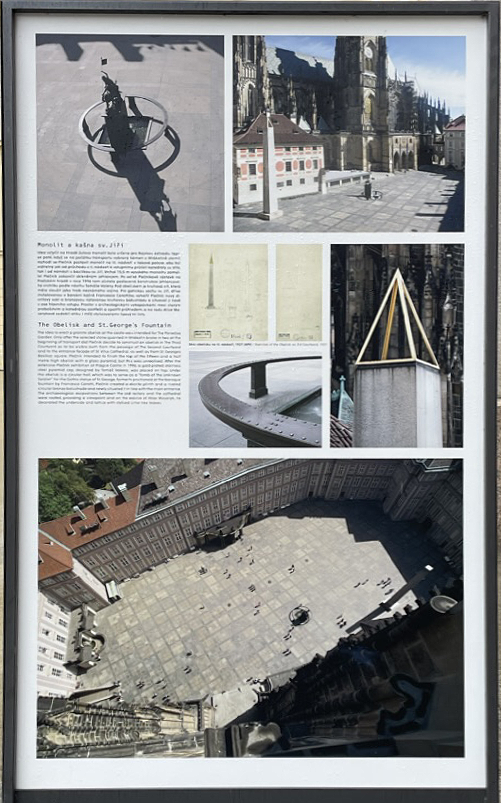

During the 2022 exhibition celebrating the 150th anniversary of Plečnik’s birth, information panels were placed at key sites to give information to the visitor on what they were looking at. Below are nine of them.

Additional photographic content regarding Plečnik

Jože Plečnik, Prague Castle

Joseph Plečnik church in Vienna

Jože Plečnik, Langer Villa, Vienna

Jože Plečnik, Zacherl House, Vienna

Joseph Plečnik in Ljubljana

Jože Plečnik, National and University Library, Ljubljana

Additional blogs of interest regarding stairs

Latvian National Museum of Art (ProcessOffice), Part 1

Latvian national Museum of Art, Part 2

The Whitney Museum: stair by Marcel Breuer

Vittorio Gasteiz: a lessons in stairs (Francisco Mangado)

Hong Kong: a lesson in stairs (Bille Tsien and Tod Williams)

Porto: a lesson in stairs (Alvaro Siza)

Firminy: a lesson in stairs (Le Corbusier)

Lexington: a lesson in stairs (Jose Oubrerie)

Vienna: a lesson in stairs (Jože Plečnik), Part 1

Vienna: a lesson in stairs (Jože Plečnik), Part 2

Geneva: a lesson in stairs (Le Corbusier)

How to design a stair