Architectural Education: about conceptual diagraming. I cannot count the number times I’ve listened to colleagues and former professors of mine promote the idea that learning about architecture begins by confronting Architecture (yes, with a capital A) with one’s prejudices about what constitutes a building. While I often question this pedagogical approach, especially as a way to initiate students to architecture—possibly denying their “suburban” autobiography—I favor that any learning about architecture (yes, with a lower-case a) should be, first and foremost, about finding a strong ethic, method of self-reflection, and empathy toward creating an art form based on space making.

Architecture, architecture and building

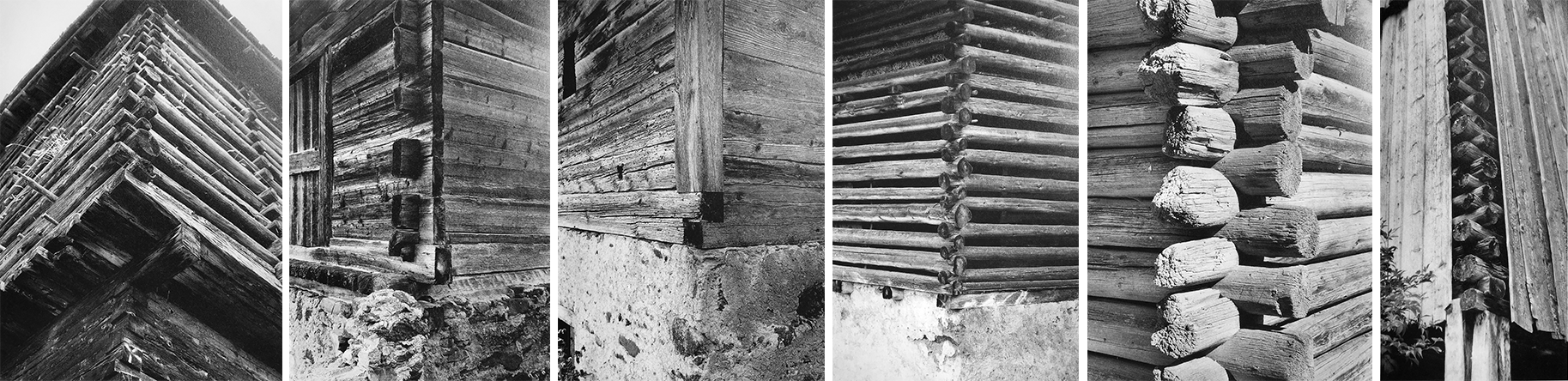

I remember as a student that the questions about the differences between architecture and building were provocative and new to me, and often accompanied by larger existential inquiries touching on inspiration, curiosity, poetry and what it meant to make my mark as a future designer. This was particularly true as my introduction to architecture was through the analysis of vernacular structures—in particular those related to rural architecture—designed by non-architects.

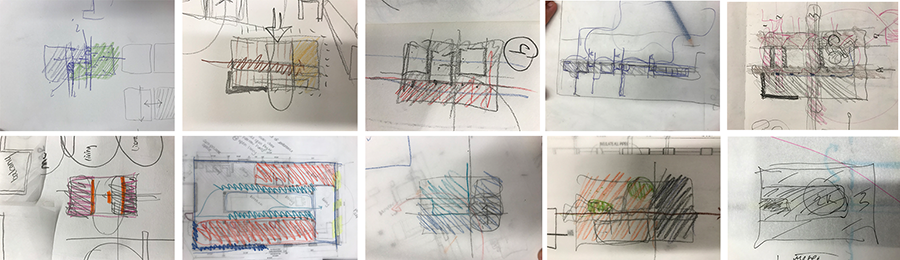

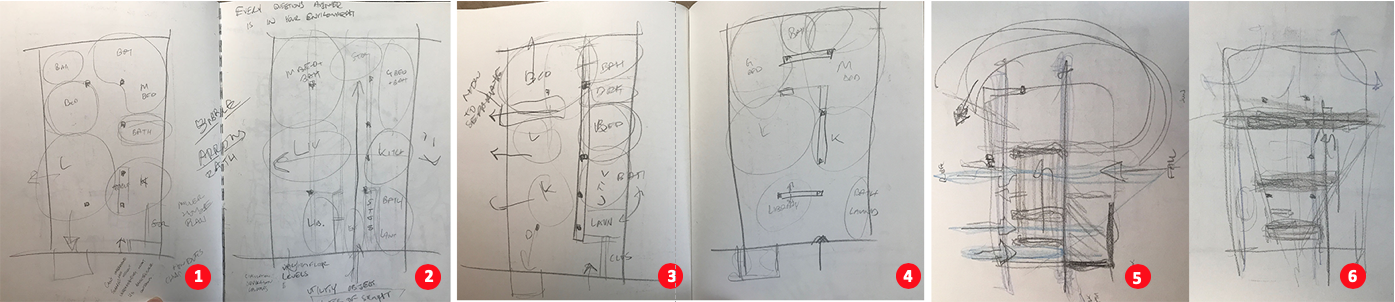

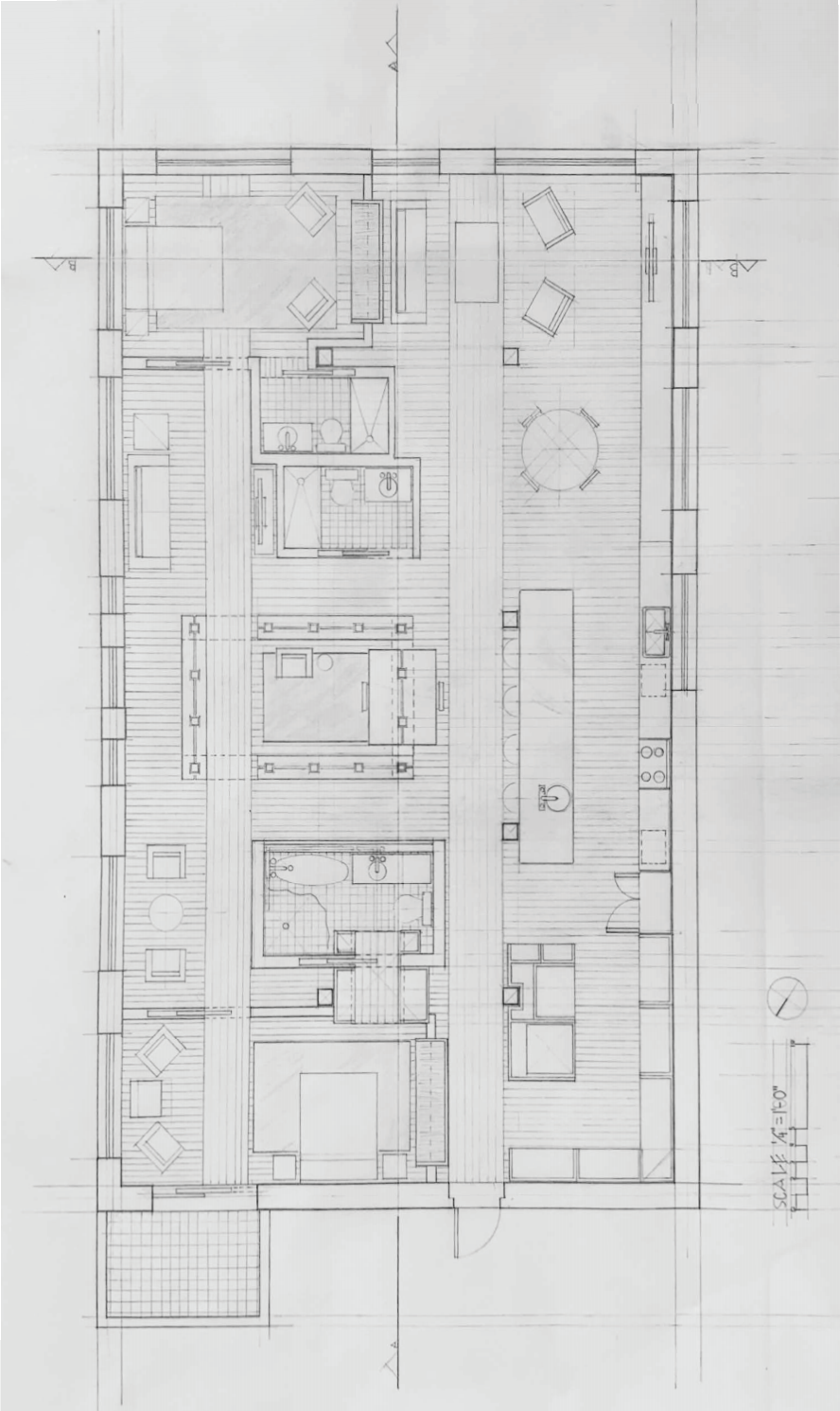

Image 1: Elementare Architektur by Raimund Abraham (1933-2010)

Image 1: Elementare Architektur by Raimund Abraham (1933-2010)

Finding answers to these queries did not live solely as theoretical proposals, but gained meaning through the act of making and crafting. In particular, we explored through architectural sketching, drawing, drafting and conceptualizing as one of the many rites-of-passage in creating a genuine and just project. Yet, having ideas about a project was one thing, which I felt came naturally, but developing concepts and how to represent them, was something of a struggle and seemed as a young student overwhelming at times, given the complexity of topics that needed simultaneous attention.

The idea of architecture

While the apprenticeship of building those skills would lead me to a solid degree of competency—a dexterity that I owe much to my faculty who introduced me to fundamental modes of representation (teaching), while eliciting my instincts about how to draw (learning)—it slowly became apparent that my interest in a polytechnic education was the balance between disciplinary pursuit and professional accountability, a position between creation and execution.

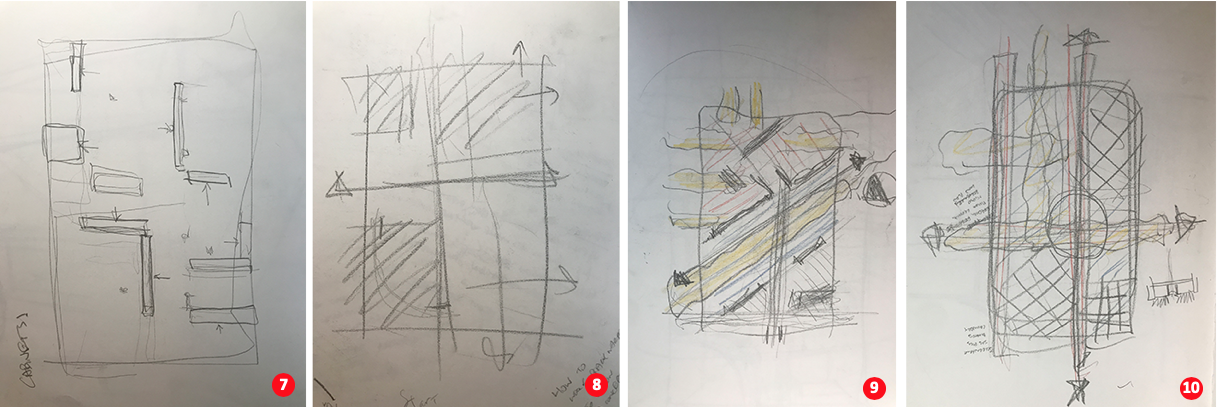

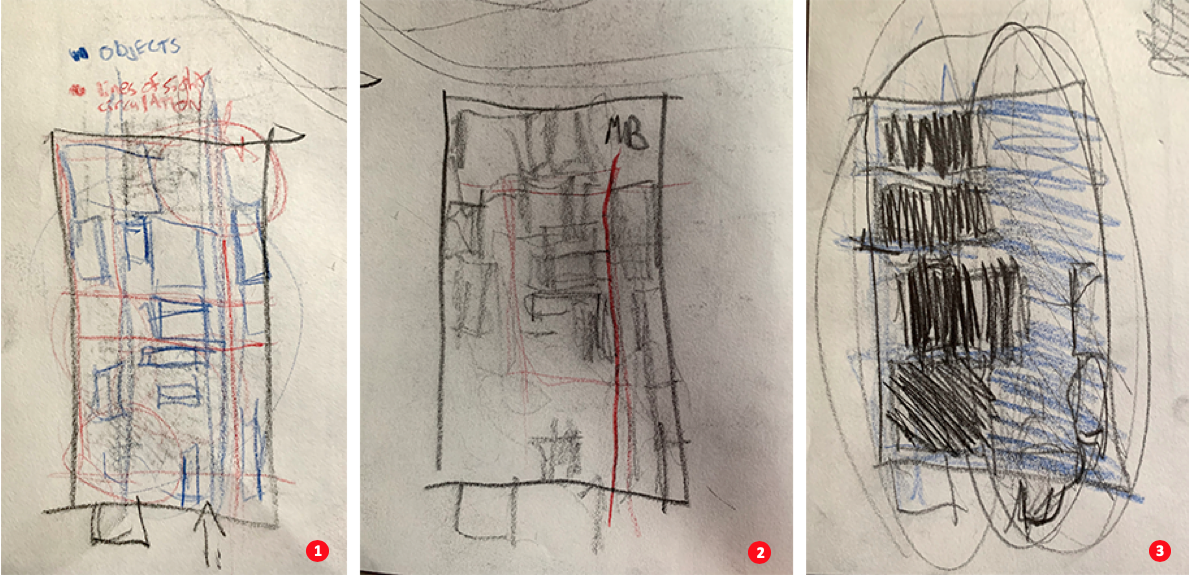

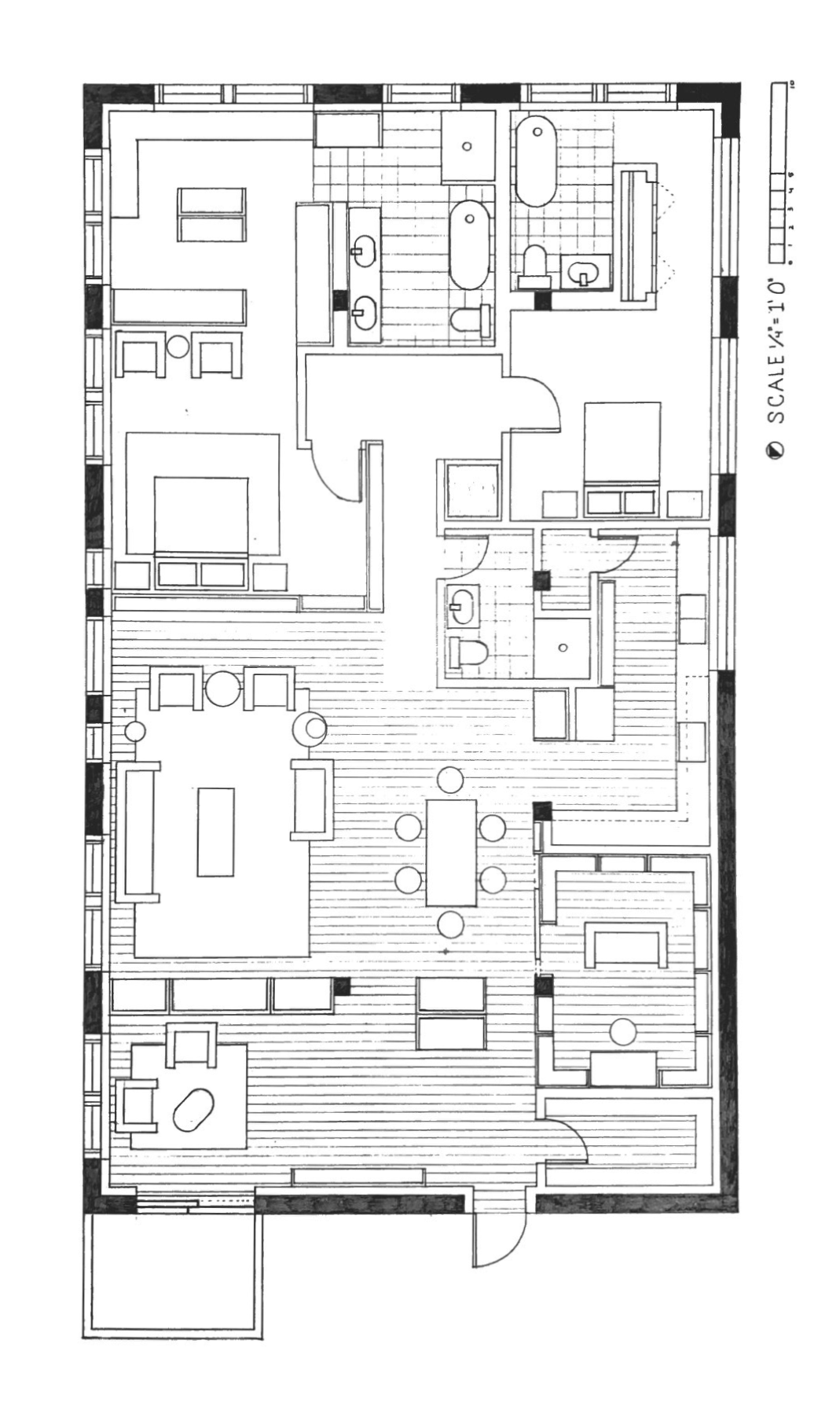

Image 2: Courtesy of Prof. Plemenka Soupitch (EPFL, Lausanne), redrawn by author

Image 2: Courtesy of Prof. Plemenka Soupitch (EPFL, Lausanne), redrawn by author

All these points led me to value the practice of architecture through a strong commitment to constructing ideas in the real world, a desire that I believed to be true at that time and now more than ever. Case in point, architects cannot forget their responsibilities in light of the current health, economic and social crisis, thus architecture must expand outside of the ivory tower so that students can become activists and community leaders engaged in building a better and more equitable society.

At the time of my education, we were trained as generalists. We learned that we would bring answers to local and global issues, a meaning that has expanded to include the usage of the term architecture as in the architecture of the brain, the architecture of the car, or the architecture of the peace treaty. It goes without saying that I very much enjoy the speculative nature of academia, and in particular my responsibilities as a professor to elicit from students a genuine sense of curiosity with a healthy dose of common sense. For those students who have entrusted me with their education, in particular those with a deliberate desire to learn about architecture, I favor creating a learning environment between theory and practice—a dialectic that I believe defines the education of an architect.

Teaching and learning

In my current institution, I teach second year design studio at the Bachelor level, and it is customary that many of my students have similar questions to those I experienced when I was at that crossroad in my education. For this reason, I addressed a number of their questions in recent blogs: how to learn to sketch, what is an iterative process, and how to move from study sketch to a drafted sketch. My overall pedagogical intentions, which subsequently reinforce the need to learn fundamental design techniques through a series of learning objectives, I ask students to engage in a line of research—original and autobiographical—with a primary focus on how to represent their ideas.

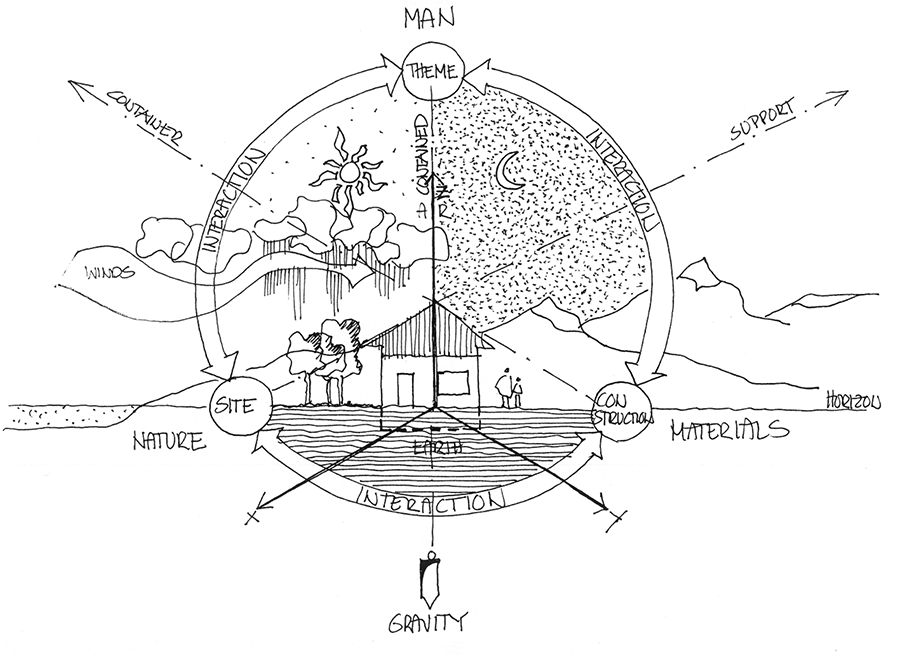

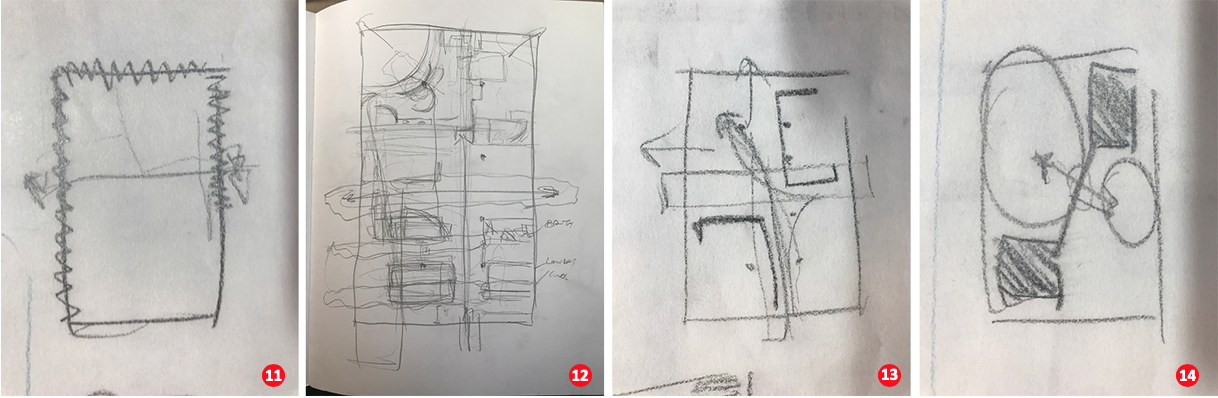

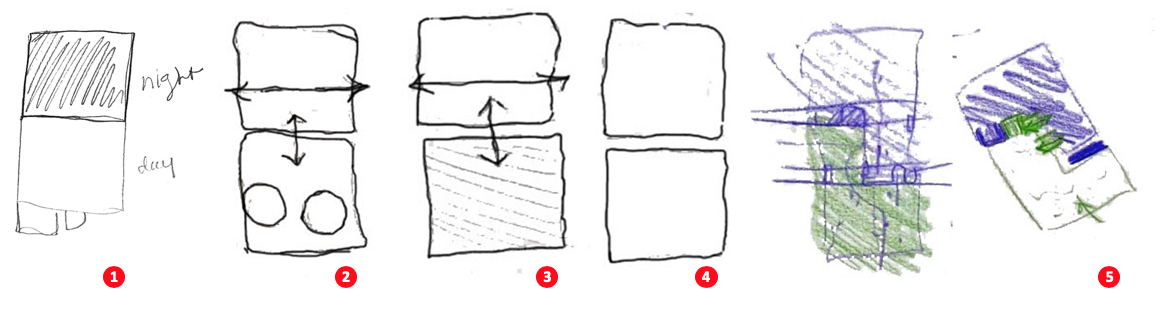

Needless to say, what seems a simple endeavor of translating ideas into space remains complex. Conducted primarily through drawing and model making, it is typically understood as a process, and owes much to a balance between designing and listening to one’s project. What I mean is that the success of any design process relies on two propositions. One is about the act of creating through drawing and sketching, and the other about listening or assessing what has been created through conceptual diagramming. And, if progress has been made as a result of this assessment, students gain an appreciation for the extent that these considerations influence the future development of their project. Image 3: Author’s diagrams done during students critiques

Image 3: Author’s diagrams done during students critiques

Conceptual diagrams

For the process of assessment to be successful, it is critical that students engage in a back and forth strategy between creating and assessing, and for this blog, it is the latter action that interests me as a pedagogical strategy. Drawing ideas conceptually remains a powerful way to mitigate between a project’s exploration and discovery.

For this reason, and regardless of the student’s studio level, I always ask them to summarize their project in the form of a diagram. This enables them to think conceptually while attending to what often seems more mundane preoccupations during a project’s development, such as program, function, use, site, structure—although each of these second-year topics are to be understood conceptually as well. The power of the conceptual diagram demonstrates both in design and the use of space how a student tackles the program of their project.

With time, the conceptual diagrams become the embodiment of the student’s understanding of their project. Typically considered as a milestone in the development of their design, it is important to state that conceptual drawings may be done at any time during the elaboration of the project. In fact, with good work habits, I encourage that they be done as often as possible for the simple purpose that creativity need not to be solely a matter of intuition, but demands constant cross-verification to move the project forward with confidence.

Three student projects

So what do these conceptual diagrams look like? And, if done repetitively over the course of the design, how do they evolve during the design process? To answer these questions, I am providing three student examples illustrating their final projects followed by a number of sketches that trace the genesis and refinement of their projects from initial thought to the final drafted plan. These rapid sketches can take multiple forms such as plan, section, axonometric, or in fact, any type of representation. In the following examples, they are expressed in plan. Critical to a successful conceptual diagram is that the drawings emphasize the abstract nature of the thought process, rather than a figurative expression of the idea.

Finally, conceptual drawings are typically done in the form of rapid gestural sketches, as both a way to summarize the state of the project while also testing the validity of the designer’s conceptual thinking. Of course, there should be a strong correlation between what is seen, and what is represented. Conceptual drawings remain one of the many tools to assist in clarifying the designer’s position.

Project 1

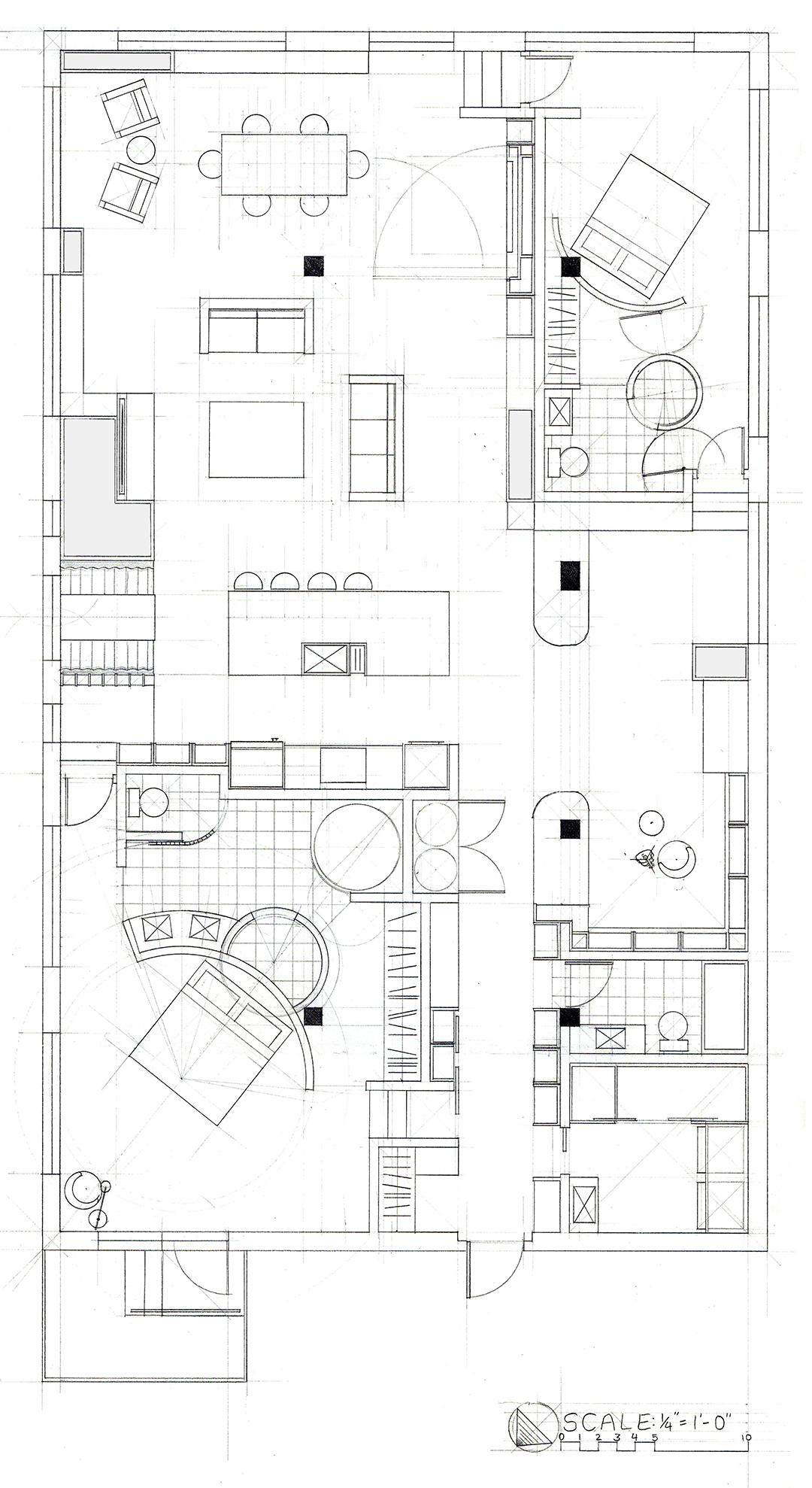

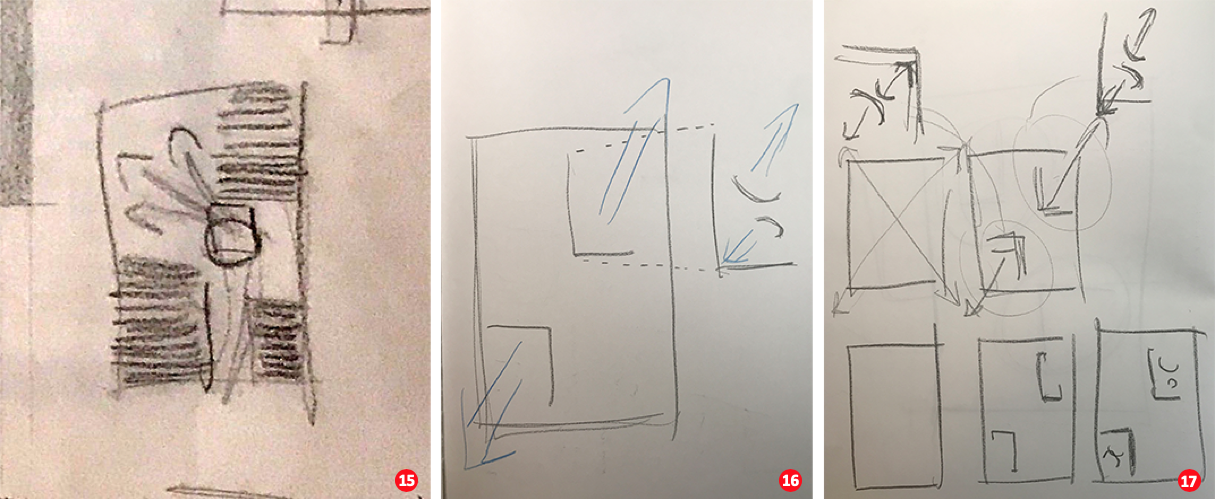

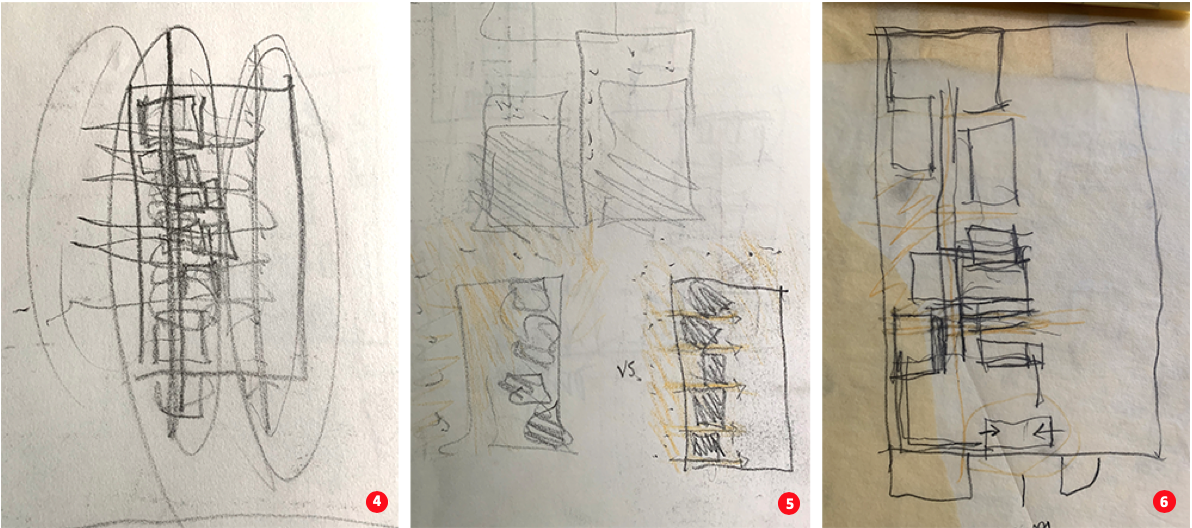

Image 4: final loft plan followed by 17 sketches

Image 4: final loft plan followed by 17 sketches

Author’s comments

In these sketches, the student favored a delicate line weight to elucidate the prompt which was to renovate a loft. First, he worked through a series of bubble diagrams (images 1-4), and next, through ideas about possible spatial relationships between assigned and interpreted functions (images 5-8). Two important features emerged as constants in most of the conceptual sketches.

1. The idea of working with the existing columnar structure (images 3 and 10), which in the final plan (see above loft plan) is translated into a series of built-in cabinets that serve the entrance foyer and on the opposite end of the loft, become a multi-functional wall that defines the edge of the guest bedroom and the living room space, which also contains a clever and efficient Murphy Bed.

2. After several functional iterations and tectonic hesitations, the final position of the master and guest bedrooms are set in place at opposite ends of the loft (image 7). Both spaces are refined throughout the conceptual diagrams and expressed through thick cabinet walls that house a number of functions incorporating innovative bathroom layouts.

As a side note, like in many design projects, there is an obvious moment of crisis (image 9) where a new concept is tested. In this case, an exploration of spaces and light but with an annoyingly formal attitude that lacked the complexity exhibited in the student’s final solution.

Project 2

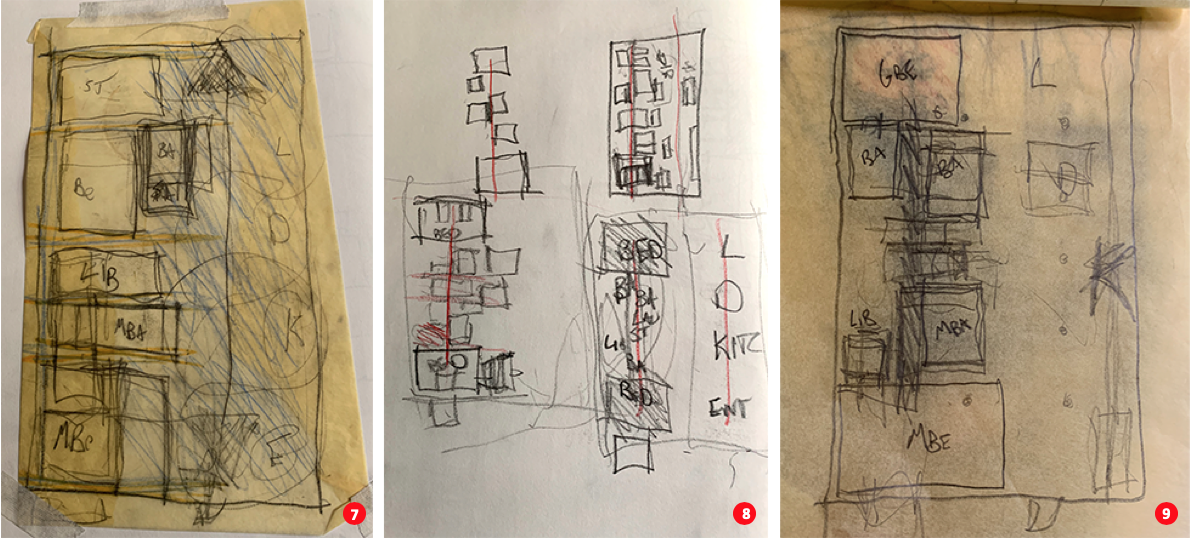

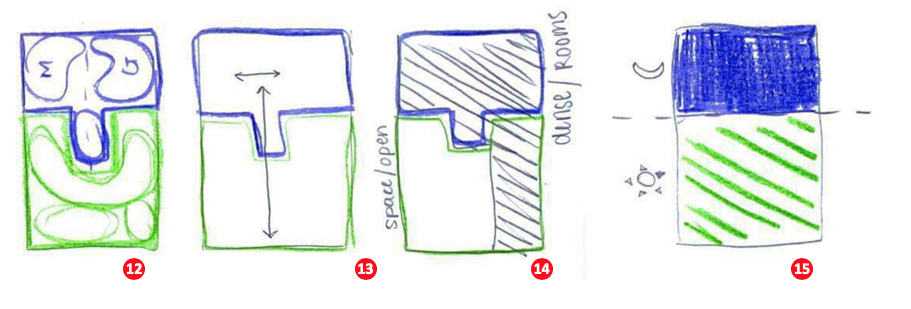

Image 5: final plan followed by 12 sketches

Image 5: final plan followed by 12 sketches

Author’s comments

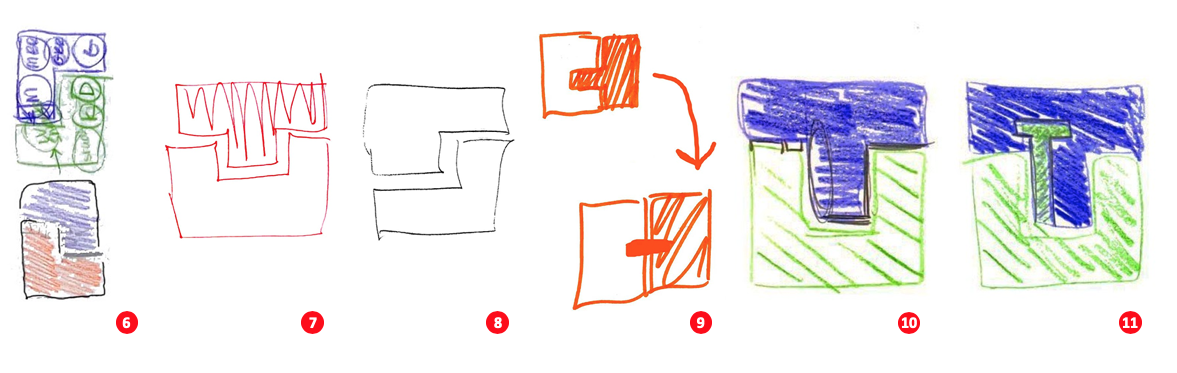

Contrary to the sketches in project 1, here, in project 2, the student’s energy and rapidity in thinking are expressed throughout each of the conceptual drawings. The boldness of the line and the primacy of the idea is accomplished through the usage of a thicker and darker lead with the introduction of color and occasional nomenclature for each space.

The idea of the loft as an organization of rooms may seem banal, but they are treated within the idea of a free plan and defined from the outset as furniture that are inhabited by spaces. A very Louis Kahn idea that is interpreted with a magnificent sense of calibration of each assigned room, exploring the notion of “spaces serving” and “spaces served.”

Similar to the previous project, each conceptual sketch features the entire loft and clearly defines a thoughtful research on the organization of closed and open spaces, either through the edges of those spaces or as dense volumes that stand out as objects within the overall organization.

Project 3

Image 6: final loft plan followed by 15 sketches

Author’s comments

The final set of conceptual sketches for project 3 show a great sense of restraint in their overall expression. Through the use of basic platonic forms, the student’s search for a simple yet complex spatial organization is accompanied by elegant diagrams. While minimalist in their appearance, they convey the strength of the author’s intent to demarcate day and night and research how a common zone can be articulated between the resulting closed and open spatial organization.

The use of color adds clarity to the readability of each concept, and is often accompanied by a massing of color to give a variety of weight to the volumes.

Architectural Education: Why Model Sketching? Part 1

Architectural Education: Why Model Sketching? Part 2