Question of Pedagogy, Part 3. Having taught second-year design studio for half of my academic life, I have always wondered how first year design exercises would benefit by being extended into architecture, thus having students learn the foundations of design and architecture sequentially, but through a single project.

Question of Pedagogy, Part 3. Having taught second-year design studio for half of my academic life, I have always wondered how first year design exercises would benefit by being extended into architecture, thus having students learn the foundations of design and architecture sequentially, but through a single project.

To contextualize my curiosity, I need to mention that in Europe—where I completed my training—architectural education does not pursue issues of pure design as an introductory subject matter for freshman. There, after a robust trimester of study in precedence focused on learning about vernacular architecture (that was the pedagogy in place when I studied at the EPFL, Switzerland), we were directly immersed into the creation of an architectural artifact, despite that most of us had little prior knowledge of the complexities that we came to be appreciated over our six years in school.

In the States, first-year design studios typically embrace various disciplines within the college where they are hosted. For example, in the institution where I currently teach, landscape architecture, industrial design, interior design, and architecture share a common first-year curriculum and pedagogy. I have only taught first year one time, and I will admit that it was not successful, despite that I understand the rich context of first year as one of the important bookends of a five-year undergraduate program.

This cycle of learning originating in a common start to degree path, is often promoted as a solid liberal arts education, which covers the social sciences, arts, and humanities. While this is all well and good, why not immerse students directly in architecture and include the additional topics as students mature and may better understand them through the design of their projects? Sadly in 2020, many first-year teaching methods find their locus in a post Bauhaus or post Cooper Union educational system.

Do not misread me, both have my deep admiration (I attended Cooper) as they were innovative for their times and thus key to most American architecture programs. History leaves us with a strong testimony of many of the programs that developed from these two institutions, and their pedagogical strategies became the hallmark for the most revered educational places in the minds of both students and faculty.

An understanding of process

To find resolution to my question for the need for continuity between fundamentals in design and architecture, I embarked on modeling one of my second-year spring projects through the lens of first year, and of process. Each project was designed to explore a thesis with a defined objective.

This meant that the learning experience was not left solely to the students’ talent and personal questions, but was based on an understanding and ability to implement process as a sine quo non-condition to measure their design intuition through the assessment of architectural topics. In this project, there was no site per se, beyond the concept of an urban, rural or suburban condition, nor was there a given program with specific functions based on as series of simple or complex space requirements.

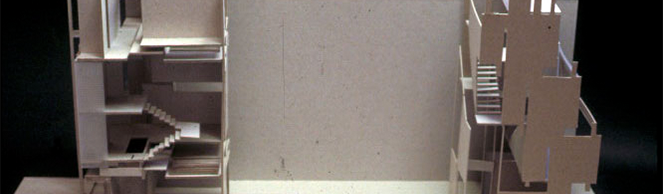

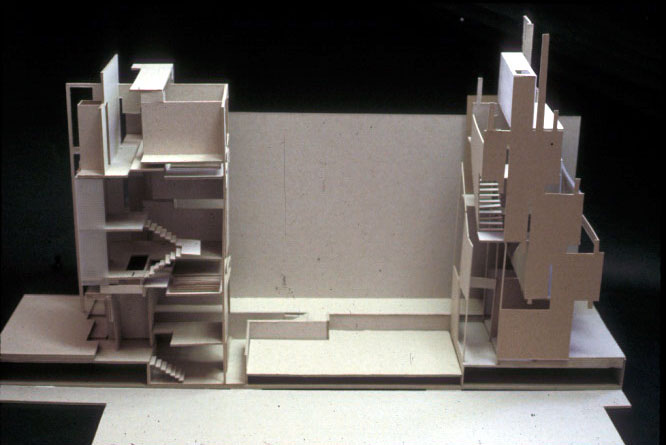

Image 1: Student artifacts (UK Spring 1987) (author’s collection)

Image 1: Student artifacts (UK Spring 1987) (author’s collection)

The project’s brief unfolded in four phases:

- An exploration of volume and space in terms of component parts (above image 1)

- Creation of an object by repetition (below image 2)

- Understanding the exception and the rule. Movement as a connecting device to organize spaces (below image 3)

- Development of a model section as illusion of depth (below image 4)

Building on Leonardo da Vinci’s quote that “Art lives from constraints and dies from freedom,” students worked individually by acknowledging that each phase constituted the design artifact for each next phase. Starting with the shape of a cube (a typical first year prompt), students needed to, through their own systems of manipulations, create a number of compositions that expressed design principles learned during their first year (above image 1).

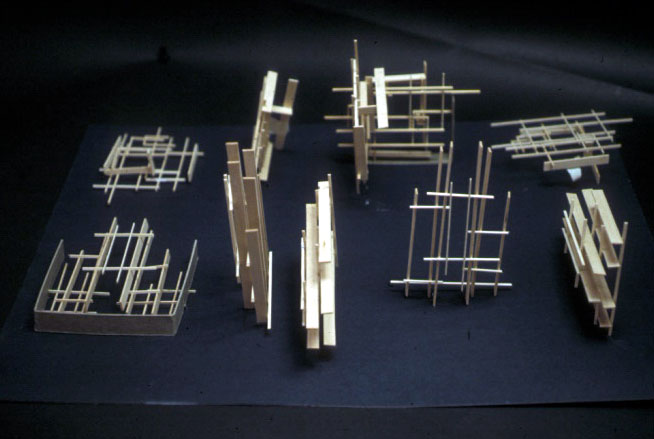

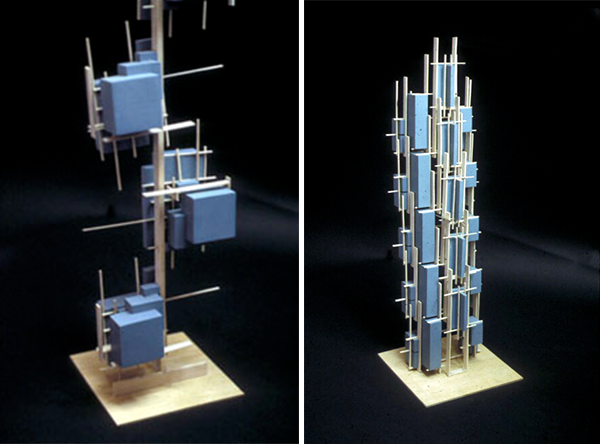

Image 2: two vertical compositions (UK Spring 1987) (author’s collection)

Image 2: two vertical compositions (UK Spring 1987) (author’s collection)

The second phase (Image 2, above) introduced volumetric complexity. Students were to select two artifacts and “duplicate” them to obtain a vertical or horizontal composition of five units. Implicit in this exercise was the importance of structure (holding up the artifact), and a strategy for organizing the new objects as a system while understanding what elements to maintain and which ones to discard in the new composition based on the need for repetition.

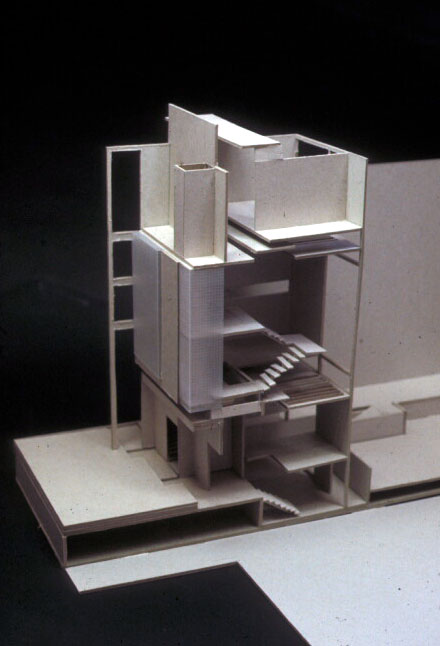

Image 3: final presentation model within an urban context (UK Spring 1987)

Image 3: final presentation model within an urban context (UK Spring 1987)

The third and fourth phases (Image 3, above, and Image 4, below) were complex and challenging as students were required to move from abstract design principles to conceptual architectural thinking. This took place by focusing on circulation, structure, site conditions and many tectonic and spatial opportunities that architecture is made of to the benefit and experience of the users.

Openings and their positions within each room or space; understanding how to engage the horizon of their chosen site; formulating a traditional trilogy of base, shaft and coronation of a building—acknowledging Vitruvius to Le Corbusier’s principles—facades, etc. Experiencing space and architectural space is the thesis of architecture, and it recognizes certain specifics belonging to the discipline of architecture. Importance of the notion of space, volume, light and surface, and their organization to enhance a user’s procession through the building, was key to the success of the projects.

Image 4: final presentation model within an urban context (UK Spring 1987)

Image 4: final presentation model within an urban context (UK Spring 1987)

One other aspect in the final phase of the project was to develop a sectional model so that working drawings would now translate thoughts and ideas into a three-dimensional artifact, no longer an object but an architectural proposition (Image 4, above). Students would balance being faithful to their two and three-dimensional investigation while interpreting and responding through a three-dimensional section. Volumes would take prominence as depth could now be visually experienced through the parallel efforts to propose and calibrate three important scales (city, site, and human).

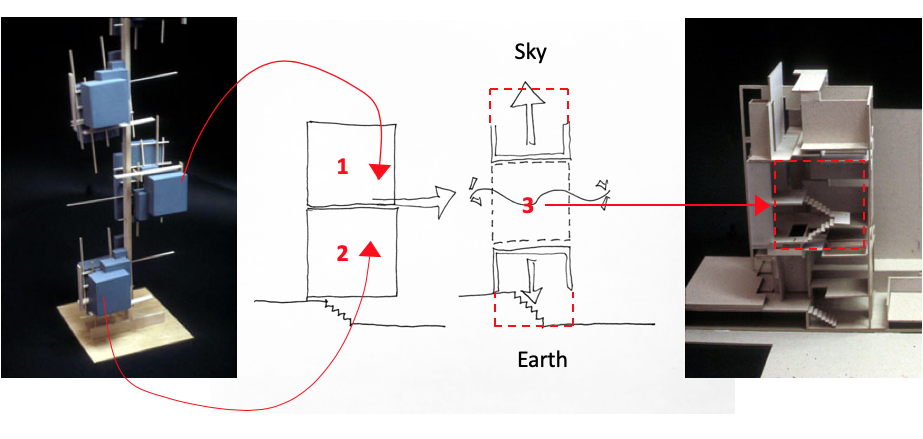

Image 5: Process from iteration to final model

Image 5: Process from iteration to final model

The student example in the above images one through four, show a strong dexterity in responding seamlessly between design and architecture. In fact, there is a strong reminder of the abstract vertical artifacts within the pavilions (above image 2 and 4 ), yet it is brought to a level of architecture that I, still today, find amazing.

(Image 5 above) In the front pavilion, there is a subtle yet visible proposition that the initial cube that generated phase 1, has now become a compositional element—for the entire left-hand pavilion that is made out of two superposed cubes, with a further emphasis on a central cube indicating a piano nobile referencing ideas of public versus private. The architectural complexity is evident but well handled with ingenuity, delight and commitment to the field of study.

I fondly keep this project and others in mind as a tangible reminder that in my opinion first-year fundamentals can and should seamlessly incorporate architectural themes, thus bringing immediate complexity to the student access to questions of architecture.

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy 1

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy 2

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy 3

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy 4

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy 5

Architectural Education: Question of Pedagogy 6

Architectural Education: The nature of IDEAS