Architecture programs, at least those that I have been associated with as a faculty member and administrator, have favored hands-on/minds-on and learning by doing pedagogies—the latter often referred to as learn-by-doing in the model of education espoused by American philosopher John Dewey. Recently, I have understood that these modes of “learning through reflection on doing,” are equally defined by the term experiential learning; a concept that emphasizes active experimentation with concrete experience, and abstract conceptualization that ends with the student’s need for a reflective observation on their work and process. Notwithstanding the particularities of each approach, each of these models refers to a theory of education that emphasizes the student’s direct interaction “with their environment in order to adapt and learn.”

Central to this learning is that it is “a deliberate process in which students, from day one, acquire knowledge and skills through active engagement and self-reflection inside the classroom and beyond it.” Architecture schools have made this approach the cornerstone of their curriculum; meaning a strong engagement within the real world. This is where many faculty have created hands-on opportunities within the design studio context to benefit direct student immersion in real-life experiences.

Learn-by-doing

During the 1980s, the learn-by-doing model expanded outside of the traditional studio setting, resulting in a meaningful civic and professional engagement in education, specifically through the creation of urban design centers. As part of the desire to establish a town and gown relationship—especially with the mission of Land Grant Universities defined by the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890—whose original mission was focused on the teaching of practical disciplines in contrast to the “historical practice of higher education to focus on a liberal arts education—the creation of urban design centers was seen as a necessary and welcome outpost for design projects that directly and unambiguously served the community.

In urban design centers, architecture students got a taste of real-life projects, enabling them to see how their design creativity had a direct impact on the world, a position often in opposition to typical esoteric and fictive program briefs that end up mostly celebrating shape making rather than understanding the profundity of architecture and its social and cultural impact. This impact was recently reflected in an Instagram post by a 2019 graduate at the institution where I now teach. He wrote: “Design is a service, you don’t design for yourself, you design for your community.”

Town and gown

Stated differently, espousing a social agenda is a way to play a meaningful role in the profession, it isn’t necessary to constantly legitimatize design talent as exceptional. The town and gown projects made students tackle urban situations within neighborhoods near their institution or in rural enclaves where design talent and design thinking became paramount in their implementable dimension. Projects were generally simple, yet went beyond the typical design brief, and in an ideal situation, were followed by a design-build approach that enabled students to witness a process from concept to execution.

While my current institution established a similar model in the 1980s at the Washington-Alexandria Architecture Center (WAAC), I continue to revere the 1993 Rural Studio created by Samuel (Sam) Mockbee and D.K. Ruth. Their approach resulted in a legacy of important yet discreet rural interventions that benefited a disenfranchised population located in the backyard of the School of Architecture at Auburn in Alabama.

Overall, it seems that the more successful community projects are those where students learn the importance of civic responsibility as integral to architecture; an opportunity to serve as a community activist and advocate for an enriched environment. In a certain way, at least for me, the presence of the human being is the constant in architecture and is sadly, and too often, relegated to a secondary role in many students’ overly designed projects. Urban and rural design centers cannot avoid that human dimension.

The education of an architect

The profession of architecture, and, in particular, the apprenticeship of architecture, has changed radically over the past three centuries. By institutionalizing the knowledge of master craftsmen, royal and state institutions in Europe were established, allowing students to acquire knowledge that had previously been shared only among guilds (learn-by-doing model). Following the industrial revolution and ending in the midst of the 20th century, a plethora of schools of architecture emerged as leaders in defining pedagogical programs to respond to what it meant to be modern.

Today, in 2020, the practice of architecture has once again changed in response to a number of imperatives that define the education of an architect—financial, technical, sustainable, and political, and most importantly over the past year, the need to reappraise issues of power, health, gender, race, and equity to the point that incorporating them within a contemporary curriculum is part of the ever-changing nature of our métier.

Unity between theory and professional competency is central to urban design centers, however, we must acknowledge, unsurprisingly, that they are intellectually rooted in the late 18th century in the educational model which will become known by the name polytechnic. This model was predicated on a vision whereby the architectural curriculum emphasized the acquisition of a disciplinary and professional knowledge that would train students to be acutely aware of the technical and social realities of their epoch.

Contrary to the tradition of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts (the architectural educational system established in the mid 17thcentury in Europe where teaching favored an aesthetic and stylistic finesse), graduates of the polytechnic tradition were educated in a post-monarchical society, and were called upon to design humble and everyday buildings. In a certain way, they were the anonymous architects of their century, thus I cannot proclaim loudly enough that I believe that the most compelling educational system to respond to today’s contemporary imperatives remains a polytechnic education.

Two models of the art of making

Recently, during a pedagogical discussion amongst faculty, I raised the question: why does our program claim to adhere to a Swiss tradition, when I, by nationality, education, and teaching opportunities in that country, believe that much of the Swissness I know is far removed from what and how we teach. A colleague suggested that it was the art of making that made us allegiant to a strong Swiss identity.

At first, I was taken by surprise by this answer, then I thought about it a little more in the context of my over thirty years teaching in the United States. For me, the art of making as a fundamental Swiss tradition means that design operates with a strong conviction towards excellence at all levels from an intellectual dimension to a pragmatic implementation. This leads to the well-known discreet quality exhibited in art, design, fashion, gastronomy, culture, manufactured products, and, of course, built artifacts.

Overall, Swiss products display “a sense of craftmanship and precision that only a nation known for its attention to detail can muster.” Made in Switzerland is a recognizable world brand that places user and art into a relationship that is more than transactional. The breath and quality across this “handkerchief” country is synonymous with an extraordinary sense of commitment to the art of making, a condition that has developed over centuries.

Tradition—as Swiss architect Le Corbusier (1887-1965) defined as the sequence of exceptional events—is about redefining timelessness with a minimalist elegance. Not as an aesthetic pursuit, but as a consequence of an intellectual need for an economy of means, always leading to simple, elegant, and well thought out solutions. This art of making expresses ancestral gestures in an innovative and contemporary way.

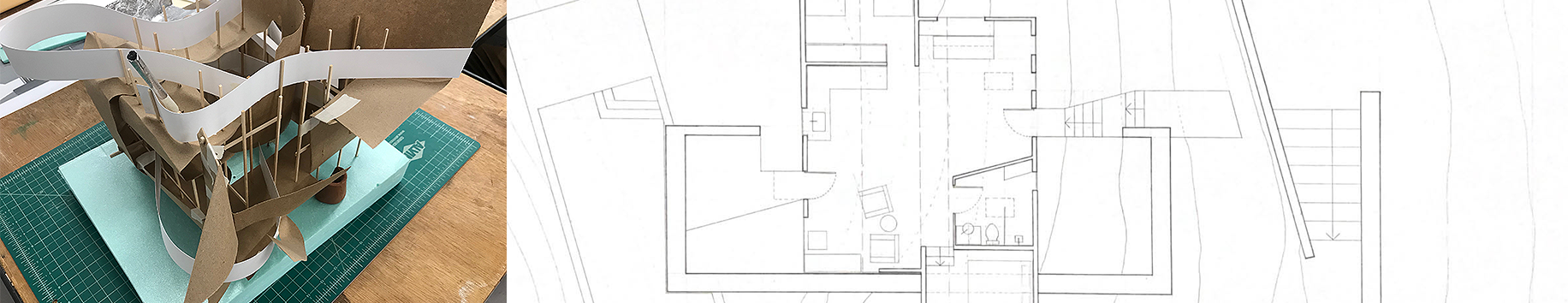

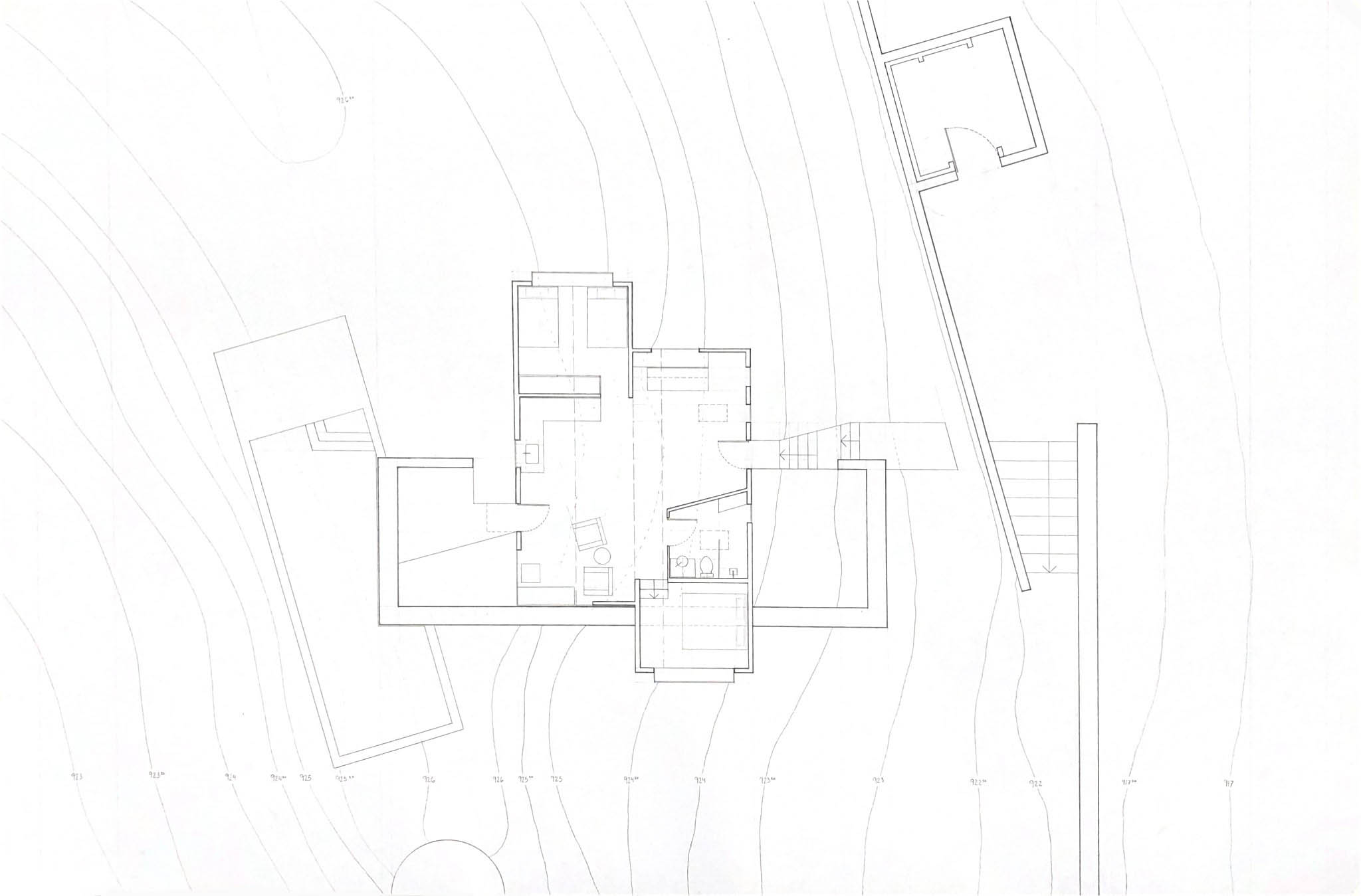

Stepping back into the present, I believe that what my colleague might have been suggesting in her response was another powerful model that can also be described as the art of making; one that relies on an experiential aspect of the learn-by-doing model; one where faculty act in a hands-off manner letting students experiment in what I call a creative messiness. This approach, which I also espouse, is opposite from rote or didactic learning, which is more anchored in the European tradition of master-student where the learner typically plays a passive role. Active experimental processes are key to this creative messiness of art-of-making path, and often result in superb artifacts. However, I often find that these resulting products then often need a Swiss “art of making” conceptual assessment in order to calibrate, adjust, and measure intuition.

The American art of making seems akin to the idea of a colleague who wrote that “Architecture is too obsessed with making…,” a comment that prefaced a pointed critique about the failure of architects in front of their prejudices. While I am taking this quote out of context, I link it to what I see as a fundamental shortcoming with this obsession of making. While this form of the art of making opens up immense opportunities in terms of process, often reaching outside of the disciplinary boundaries of architecture because of a lack of self-imposed limitations, the downside of this approach leaves little rigor to reflect on what was intuitively generated.

In this process of making, the designed artifacts emphasize qualities of an object, as the visual components are often striking and predominant at first glance. If well executed—as a genuine endeavor—within this American model of an art of making the created object is unique and authentic and expresses a conceptual approach. The immediacy of the experience, intensity, and intuitive qualities are rarely achieved through a Swiss art of making.

In conclusion

Regardless, as learning is autobiographical, there is no perfect learn-by-doing architectural education, thus the promotion of both types of the art of making are necessary for students. We can ponder pedagogically our allegiance to one or the other, but at the end of the day, students have the responsibility to understand which techniques are favored at specific moments during the development of their project.